Interview: In This Corner of the World Director Sunao Katabuchi

by Andrew Osmond, Director Sunao Katabuchi has worked on an astonishing range of anime. Many Western fans may still be most familiar with him as the director of the brashly ultraviolent series Black Lagoon, but his new opus In This Corner of the World is as far from that as Ozu's Tokyo Story is from Tarantino's Pulp Fiction.

Director Sunao Katabuchi has worked on an astonishing range of anime. Many Western fans may still be most familiar with him as the director of the brashly ultraviolent series Black Lagoon, but his new opus In This Corner of the World is as far from that as Ozu's Tokyo Story is from Tarantino's Pulp Fiction.

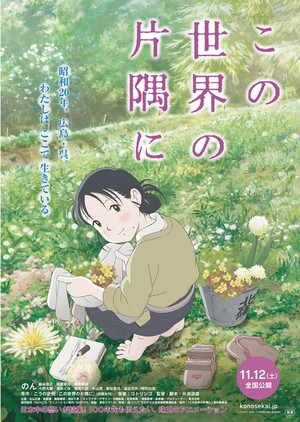

Based on the manga by Fumiyo Kōno, the film is a delicately-drawn period drama showing the Japanese experience of World War II from the viewpoint of a young housewife, Suzu, who lives in a coastal town near Hiroshima. The saga of Suzu has collected a dizzying number of accolades in Japan. The film won the Japan Academy Prize for Best Animation of the Year, and was rated 2016's best Japanese film (animated or live-action) by the prestigious film journal Kinema Junpo. (By the way, the last time Kinema Junpo had given an anime the top spot was in 1988, for My Neighbor Totoro.)

Katabuchi's other films include another period drama, Mai Mai Miracle, about the lives of children in the 1950s, and a feminist fairy-tale film, Princess Arete.

Special thanks to Rod Lopez of GENCO and Jerome Mazandarani of Animatsu for making this interview possible, to Andrew Kirkham and Kazumi Kirkham for their wonderful translation, and to Andrew for his extra questions.

You have worked on a very wide range of anime, from Black Lagoon to Mai Mai Miracle. Why did you want to direct this film?

You have worked on a very wide range of anime, from Black Lagoon to Mai Mai Miracle. Why did you want to direct this film?

I think all the films I have made are connected. Before this film I made Princess Arete, which is a story of a girl who tried to believe in her own self-worth. I wanted to be like her; I wished that I was successful. Yet when we look to the future we realise that it is not necessary to achieve the perfect future we believed in for everyone. When I thought about that, I thought I had to create a film where criminals had no other choice than a life of crime, like (the situation) in Black Lagoon.

Then I thought that as I could describe a criminal lifestyle, I could also describe the real life of children. With this in mind I made Mai Mai Miracle, wondering what I could tell them. Mai Mai Miracle was set in Yamaguchi prefecture in the 1950s. I was born in the '60s and it was easy to imagine this, following my childhood memories.

Shinko's mother, one of the characters in Mai Mai Miracle, became pregnant with Shinko in 1945. Living through the war period, she married at the tender age of 19. Seeing the way women dressed differently during the war enabled me to easily imagine their horrifying existence caused by living with all the bombing. However, Shinko's mother was very calm and always smiling. Ten years earlier, she would have lived a very different life and I wanted to portray that. At the time I came across the book In This Corner of the World by Fumiyo Kōno and it inspired me to make a film of it.

How would you describe the character of Suzu, the film's heroine?

How would you describe the character of Suzu, the film's heroine?

She has a lot of imagination and the talent of drawing. Her right hand can tell many things. It can explain a story through drawing. However her mouth never talks about these things.

Maybe she doesn't believe in herself or maybe she assumes she is talentless and just a normal woman. However, that's why she trying to make her life plentiful. During the war she is always picking flowers, planting vegetables and trying to make delicious food for her family, despite the shortages. Throughout it all she is always smiling.

To me Suzu so sweet and adorable, and also she seems irreplaceable. I felt it was almost too much to bear that the indiscriminate bombing could harm an individual like her.

The film shows a part of Hiroshima that was completely destroyed by the atom bomb. Can you describe the research that you needed to do to present this area on screen?

I think it is the same for everyone in Japan, but for the citizens of Hiroshima it is very important to remember the events of 1945. I feel we have to pay close attention to details. In spite of ourselves, we could give misinformation or present it the wrong way and this would hurt the feelings of people who experienced the atomic bomb, the bereaved relatives and so on. (I had) this point very much in mind.

I am not a local so it was difficult for me to know or even visualise the many places in and around Hiroshima which Fumiyo Kōno drew in the manga. First of all, I put the atomic bomb to one side. Our initial job was to research all the locations in Hiroshima featured in the manga.

I realised the place where Suzu and the boy Shusaku met for the first time was really near (what would be) the epicentre of the atomic bomb. For this point the author had to do careful research. Also she believed somebody would understand the hidden poignancy of this without having it fully explained to them. This place is very close to the building now known at the Atomic Bomb Dome.

We also know that the bridge where Suzu and Shusaku were standing was a specific target, shaped like a letter T. The more research I did, the more I realised that place where the atomic bomb hit was a normal residential area of the city. So I was very careful.

I had lots of books and photos. I met with lots of people who were children in 1945, as all the adults from that time and place had died. They had lots of stories to tell. From these tales I knew how to portray the area and decided to do so.

Reportedly, you needed to modify one shot of the area twenty times before the shot was satisfactory. Can you talk about the process of making this shot, and why it was so difficult to get it right?

Reportedly, you needed to modify one shot of the area twenty times before the shot was satisfactory. Can you talk about the process of making this shot, and why it was so difficult to get it right?

There are quite a few buildings still remaining from the period before the A-bomb. I am sure that one of them is the rest house in the peace park. The second floor is actually the Hiroshima Film Commission now, so we used it as the base for our Location Hunting.

The rest house in the peace park used to be a kimono shop. At that time it was quite a huge shop. I drew this building as it was before, as I wanted anyone actually standing in front of the building to be able to recognize and touch it physically.

I realised when I tried to feature the building in the film that I had to include the surrounding area. In front of this shop was another one called Õtsuya, but there weren't any photos available for this. Before the A-bomb, many buildings were evacuated and purposefully destroyed by the Japanese themselves.

Taisho Kimono Shop was tall and thin. Because of this, we had to show lots of surrounding buildings to fill the wide film frame size. So I was forced to draw the Õtsuya shop. Although there were no photos of the actual shop, some other photos showed a section of this building and its nameplate could be seen. I also found an aerial photo. I checked the building plans, in an attempt to find out its size, and we started to draw (the shop).

We went to Hiroshima with this and talked to the people who were children at that time. Of course, there was no one who could explain precisely what the buildings really looked like, because that was over 70 years ago. However, we gleaned some very interesting information from them and started advancing our drawings. We kept showing them what we had done and checking if they felt it was an acceptable portrayal.

A gallery space allowed to us to display our drawings, and by chance one local saw them. That person was the daughter of (the owner of) another shop called Hatsukaichiya, which was next to the Õtsuya shop, but it was actually outside the frame in the film. She had strong memories of her girlhood. She remembered the window height difference between the two shops, and that in front of the show-window was a brass hand rail.

“Why do you remember that?”

“I'll tell you why I remember that. It is because I used to lean on them and I still sometimes feel that on my back”. It was a precious memory for her.

Also we got a story from a person who was a school-friend of the Õtsuya owner's daughter, who died in the A-bomb.

Like this, we pieced together little bits of information and cross checked each bit.

How many people were you able to interview about their memories?

How many people were you able to interview about their memories?

More than ten people. All of them were children at that time. Almost all of the adults were at the A-bomb site, but the children were evacuated to the suburbs in advance. They survived the war. There was a high school teacher who interviewed them about the surrounding area. I became friends with this teacher and met (these people) via him.

Do you or your family have a personal connection to the Hiroshima area?

When my film Mai Mai Miracle opened in Hiroshima I visited there for the first time. Before that, Hiroshima was not known to me. However, my father was born in Kyushu, Saga Prefecture. Saga is next to Nagasaki. My father was an elementary school boy on 9 August 1945. He said he saw the mushroom cloud 50 kilometers away.

As it was far away, there was a time delay. He remembered very clearly that the house windows shook wildly because of the shockwave. It is almost like a sort of involvement for me.

Do you think your understanding of Japan at this time has improved through making the film?

As I told you, my film Mai Mai Miracle was set in the 1950s. By following a memory I could reach back to that time. However, the 1940s seemed a very different proposition.

For example, women were wearing monpe (work-pants), a kind of trousers. I wondered why they weren't thought ugly or style-less, as the women were young ladies who naturally wanted to look nice.

In the original manga, Suzu began wearing monpe in December 1943. Through my research I realised ladies didn't wear monpe until Autumn 1943. Most of us believed that during the war women wore monpe all the time. That was wrong. There were fuel shortages in the winter of 1943. It was bitterly cold, so cold their kimonos were cold on their legs.

Also tabi (Japanese traditional socks) were difficult to acquire at that time. Monpe kept them warm and so they became a trend at the time. That was quite a shock to me. From this situation I could really understand the reasoning. It didn't matter how it looked, as it was so cold.

A newspaper article of that time said (the women) shed the monpe because it was getting warmer. So in this film Suzu doesn't wear monpe during summer 1944. If she went out she wore monpe to keep up appearances, but in her daily life she did not wear them. So when I knew about that, the 1940s era was not so strange to me anymore.

There is a one-piece (clothing) that survived the A-bomb explosion and is preserved in Hiroshima. I saw it in a photo-book. There were a lot of delicate and sweet things. I was surprised by the one-piece, as it was very different to my expectations. So (the women) did not wear just monpe on their own, but sometimes a lovely one-piece under them. They were basically very fashionable.

discuss this in the forum (3 posts) |