Review

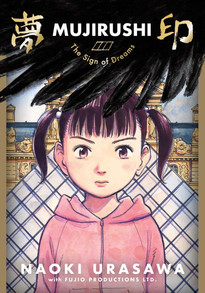

by Rebecca Silverman,Mujirushi: The Sign of Dreams

GN

| Synopsis: |  |

||

Kasumi Kamoda's life derailed when her father decided to cheat on his taxes, costing the family everything. When her mother then wins a luxury cruise with American celebrity (and presidential hopeful) Beverly Duncan and runs out on her husband and daughter, her dad throws all of his remaining capital behind an idea to manufacture Beverly Duncan masks as a way to mock the candidate. But that idea goes belly-up all too soon, leaving the Kamoda family with no where else to turn…until Mr. Kamoda finds a strange symbol and follows it to an even stranger man. The man makes a proposal: steal Vermeer's The Lace Maker from the Louvre in Paris and leave a strange stone behind and get out of all of their money troubles. When something sounds too good to be true, it usually is, right? Right? |

|||

| Review: | |||

Naoki Urasawa is only consistent in that all of his stories are good in both art and story – the settings of those stories, as well as their genres, vary widely across his bibliography. Mujirushi: The Sign of Dreams is the sort of bizarre story that only someone who has mastered his craft could really pull off, and it's a definite credit to Urasawa that he did, because the various twists and turns that it takes can leave the reader feeling at sea at times, and even wondering what on earth he's trying to do. The end result is a book that really only fully comes together after you've finished it, and that actually benefits from multiple readings. The truth of the tale is in there, but it's not one Urasawa is going to hold your hand through – if you want to know the meaning behind it, that's work you're going to have to put in yourself. That can be a difficult thing to pull off, with many works – manga or otherwise – that attempt it turning out pretentious and overbearing. That may be part of the thinking behind the mysterious man known only as “The Director,” a rabid Francophile whose design is almost a caricature; certainly most times we see someone drawn with his prominent buck teeth and stylized hair, that's a symbol for someone who isn't entirely in touch with reality and is likely intended as comic relief. In fact, the Director's design is almost lifted wholesale from the Osomatsu-kun franchise, where he's the con artist Iyami. Since it doesn't feel entirely likely that Mujirushi is a spin-off of that world, this is likely meant as a red herring – if the Director looks like Iyami, that's to distract us from the more serious story that he's a part of. In this he absolutely succeeds, because there's a much darker theme running through the volume. Kamoda has bankrupted his family with his foolish ideas, resulting in his wife leaving him and he and his young daughter Kasumi being close to having nothing left. Kamoda is contemplating suicide when he finds the symbol – three squares in a row – that leads him to the Director, and if he wasn't thinking about killing Kasumi alongside him, he was still going to throw himself in front of a train with his seven-year-old (roughly) daughter standing right next to him. The Director offers Kamoda hope, telling him that the row of boxes is the symbol of hope, and that to get his life back on track, all he needs to do is go to Paris, steal the Vermeer masterpiece The Lace Maker, and leave a stone with the same symbol in the Egyptian collection. Kasumi rightly suspects that this could be another one of her father's spectacularly bad ideas, but Kamoda needs the dream so badly that he takes the Director up on his offer. There are several competing story threads that are woven throughout the books, all of them anchored to the Director himself: an art smuggling ring with a Japanese leader, a young firefighter who was raised by a Japanese woman who boarded at his grandmother's, the grandmother's past as a chanteuse in the 1960s, the Kamoda family's misfortunes, and the candidacy and early presidency of American billionaire Beverly Duncan. Although these at first seem only tangentially related – the story never gets to America, and the singer almost appears to be a distraction – by the end of the book they've all come together to provide a mostly complete picture of what brought all of these people into each other's orbit. Even without this being an impressive feat of storytelling, the satisfaction that this provides to the reader is arguably the strongest element of the graphic novel, bringing new meaning to the idea that you remember things by how they end. As should perhaps be expected from a work about art, the idea of how one work of it can have different meanings to different people is an interesting piece of the whole. The Director begins by saying that the Vermeer painting he especially loves isn't necessarily most people's favorite work in the Louvre, or even of Vermeer's. This sums up the symbolic element of art within the story – to each person who sees it, the Director's “sign of hope” is something different, much in the same way everyone in Japan assumes that the bowls he pulls out are rice bowls instead of vessels for café au lait or hot chocolate. The shape and size are similar, so it becomes your own cultural understanding that dictates how you see it. That of course goes back to the Director looking like Iyami from Osomatsu-kun: because we have that instant association, we see him as either the character himself or as a caricature of a pretentious Francophile. In neither case are we necessarily seeing him for who he is. In Oscar Wilde's epigraph to The Picture of Dorian Gray, he muses on the contradictory nature of art, ending with the line, “All art is quite useless.” That comes to mind while reading this book, not because art truly is useless, but because it truly is all things at once to all people. Urasawa uses the thinly-veiled look at the 2016 U.S. presidential election as a way of saying this by looking at the success, failure, success pattern of Kamoda's mask business, but also in the simple fact that somehow that symbol of the three squares in a row can become anything depending on who is looking at it. Maybe art is useless, but maybe it can also function in ways that no one is fully aware of, as we see here. Part caper, part drama, and part theatre of the absurd, Mujirushi: The Sign of Dreams is about how we choose to see it, just like any other work of art. |

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall : A-

Story : A-

Art : A-

+ Comes together in a way you might not expect, tightly plotted with a lot of interesting elements. |

|||

| discuss this in the forum (1 post) | | |||

| Production Info: | ||

|

Full encyclopedia details about |

||