Answerman

Nobody Loves The Weeaboo

by Justin Sevakis,

I've been eating really healthy for the last week or so. I had a salad for lunch, and a salad with some tacos for dinner. Lots of fish.

This is driving me crazy, and I'm absolutely FIENDING for junk food. Needless to say, i'm a little bit on edge.

Ah, summer...

seabiscuit.0 asks:

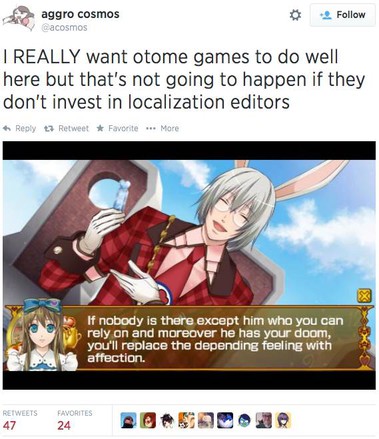

I can not tell you how happy I was when quinrose released Alice in the Country of Hearts for Android and iOS in English. It is the game my customers request the most. Yet it only turned out to be another machine translation level failure.

Why is it that whenever a japanese company tries to bring their stuff over and do the translation themselves Like key did with planetarium the translation is almost always horrible. Is it that the japanese think the translation does not matter or that they can not get a half decent translation done?

I'm not a gamer, so I hadn't seen first-hand just how bad of a translation this poor game actually got. It'd be hysterical if people didn't actually care about this game. I mean, it's "All Your Base" level Engrish, of the level even Google Translator seems to rise above these days. As visual novels are predominantly text, this presents an obvious problem: lines range from amusingly off ("I don't want to be with the suicide rabbit!!!") to just plain incomprehensible. Reviews on iTunes and Google Play seem to indicate that the quality varies depending on what paths you take. The prospect of slogging your way through this makes me think of watching an anime with Chinese bootleg subtitles.

Of course, the Japanese completely screwing up English translations is nothing new. Bad Engrish translations are everywhere. Terrible English bit performances crop up in anime now and then. Occasionally they even try to make an English dub in Japan, with predictably unwatchable results. This is what tends to happen in a country where everyone has to take the same foreign language in school, but the program kind of sucks and nobody retains any of it. The Japanese relationship with English in general seems to be something akin to, "you want me to program an operating system from scratch? No problem, I took a computer programming class in 9th grade!"

Native English speakers never see this sort of haughtiness from anybody Japanese in person. As anyone who has ever learned a foreign language knows, whenever you're in front of a native speaker, you realize that you're going to be immediately called out, and seize up. You get nervous, you start to sweat, and manage to eke out an awkward few sentences at most. But among your own friends who are on your level, you'll speak that language endlessly, no matter how terrible it actually sounds. (see: any high school or college anime club.)

And that's the problem, really. In a sea of equally-terrible English speakers, nobody feels all that bad or self-conscious about their skills, and then they bite off way more than they can chew. This sort of situation tends to happen at smaller companies who don't have any actual non-Japanese working for them, or even someone who's studied or worked overseas. In a bubble of similarly poor English speakers, it's easy to think, "hey, I've got this!" And when you're on a tightly budgeted project, it's easy to accidentally think that translating into English is something you can handle. Nobody in your immediate vicinity will tell you otherwise.

This is the problem whenever a company sets out to do anything that's not in a language they speak well -- nobody in a position of power can really understand how good or poor the final product is. The project producer in this case likely couldn't even tell the difference between a machine-made translation and a proper one. This is clearly not an ideal situation, but it comes up all the time. Don't even get me started on when Japanese licensors have to approve English dub scripts, and consequently don't understand ANY common English expressions or idioms.

In case you couldn't tell, yes, I have been on projects where a bunch of Americans have tried to present reports in Japanese, only to be told that we have made utter fools of ourselves and the document we labored over for weeks is completely unintelligible. This is very much a two-way street.

Jake asks:

I have recently become interested in watching Naoki Urasawa's series MONSTER but I have several questions surrounding its release. I am aware that Viz only released one volume due to low sales, which is understandable. What I cannot seem to wrap my head around is why Viz dubbed all 74 episodes if they knew that the first box set sold so poorly? Just dubbing it alone must have cost a fortune, let alone licensing, translation and marketing. I am aware that it played on several networks like SyFy. Were they were contractually obligated to finish it? Also why is it not available anywhere streaming or digital purchase? I also find it suspicious that it was not that popular, since Guillermo del Toro was trying to turn the property into a live action series for HBO, and an Australaian company released the entire series on DVD only in 2013. Who holds the license, since Viz seems to have completely dropped MONSTER?

The cost to dub MONSTER in its entirety must've been incredible -- I estimate north of $500,000. It's really too bad that it absolutely TANKED on disc. (And it did tank. Trust me, I've heard some hints as to how bad.) Viz's contract has since lapsed, and so the rights for North American distribution are back in the hands of the licensor, which I'm pretty sure is ShoPro (Shogakukan Productions Ltd.). Now, that IS one of Viz's parent companies, but that doesn't mean Viz got it easily or for free -- they still have to go through the same channels as everyone else and pay a big license fee, which goes to the production committee. As MONSTER was a big hit in Japan and Naoki Urusawa is a household name, that can NOT have been cheap.

But why would they continue dubbing the show if it tanked? As you said yourself, the show had already gotten picked up for broadcast in several markets, and ShoPro had already promised English versions to those TV networks. Having a ready English dub would also help sell the show in other territories. Whether Viz or ShoPro was on the hook for paying for those dubs that Viz never utilized, we'll never know. We'll also never know if Viz ever had online rights for the show and just gave up on it, or those stayed with ShoPro (or were turned over to a TV network as part of a broadcast deal). But we do know that the show did get sold to Australia. I have no idea if it did well there or not, but I do know that a different company -- Nippon Television -- was in charge of selling to that market. See how complicated this all gets?

As for the HBO project, Monster was a big title that had decent buzz in Hollywood simply for being good, and Del Toro wanting to develop a live action series really has nothing to do with how well the anime did or didn't do. (Unless a property is COMPLETELY mainstream, Hollywood seldom adapts things seeking to cater to the existing fanbase -- they're usually trying to build a completely new one from scratch.) Regardless, Viz's contract is over, no distributor has US rights, and it's unlikely that will change for a while. Or at least, not until the show gets so old that nobody in Japan cares about it anymore and it gets cheap enough to license rescue that someone wants take another swing. And with it being an Urusawa title, we might be waiting a while.

Rafael asks:

I think it was Zac that said (on Twitter) that he didn't end up reviewing Penguindrum for ANN because he was not yet confident that he could fully engage with all of the themes it had. It got me thinking: when doing a review of a piece of media (particularly something as dense as Utena or Penguindrum), is it better to engage all of its themes all at once in one essay? Or is it better to laser-focus on one theme, or a few that are closely related, to make a point? Is it a flawed review if you discuss the thematic elements in a show, but then in the future, realize you ended up missing a few things?

You are asking for clear lines and rules when discussing a work of art. These do not exist. The important things when you write a critique of a piece of art are that you approach the work with an open mind, and that you are intellectually honest with yourself in analyzing what it had to say. I don't want to put words in Zac's mouth, but Penguindrum is a very thematically dense TV series that it takes real effort to process and unpack. If I felt that I was missing something that was required to decode something that may be important, and that I needed to research more before I could offer what I considered to be an informed opinion, I too would recuse myself.

For the reader, a "review" is a way to make an informed opinion about what to watch, or a jumping off point for further discussion. For the reviewer, that writing is usually simply a reaction, a gut reflex given verbal form. I liked this. I didn't like this. That was cute. This was horrifying. For most anime, movies and TV series, that initial reaction is sufficient, because that's all there is to talk about. Most shows wear their subject matter on their sleeve, and don't get too caught up in symbolism and inner meanings. This isn't a reflection of their quality, but simply of their storytelling ambition.

Shows like Penguindrum are the stuff that require more than that, and they're the real test of a critic. Honest discussion requires more than the "liked/disliked" stimulus response of most art: they require pondering and introspection. Our reaction to the work should be more than what our gut tells us, because if it was effective, it should make us think. When I see a film that really strikes a deep chord, I usually go somewhere quiet and have a glass of wine or a slice of cake or something, and sit by myself. I reflect on what the characters go through, their inner lives, and how it parallels real life experiences that I know to exist, either within myself or in history. It's a meditation to find meaning, not unlike what people do with ancient religious texts. Once I find my conclusions, I find myself with a lot of thoughts to get out. Writing is my instinctive next step.

For a critic, you only get one chance to have a big, public reaction to a work of art, and when that work of art is important to you, it's imperative to get it right, to leave no thought unexpressed, to do a thorough job of unpacking your thoughts and conclusions about whatever that work had to say, in a form that's concise and organized and readable. Only the critic knows if he/she got it right, and I personally still kick myself over reviews I'd written years ago, wishing I could go back and write about them again. But you largely only get one chance. You can publish another essay if you like, but that follow-up will never be as relevant or as widely read.

The reader will be unaware that any of this great battle for truth in the critic's head will have transpired. As it is formed partially by that critic's world views and life experience, it is completely unique. Sharing those reactions is THE reason to write art criticism. It's a reflection of the critic's spirit in union with the art that provoked it. It can only be wrong if the critic was dishonest with his/herself during its conception, forcing the work in question to become something it's not. At its worst, the resulting article is irrelevant, but at its best it fosters meaningful discussion, and brings out themes and thoughts in others. Through the free exchange of these ideas, people find more meaning, and the value of the art grows within the public's consciousness.

The opportunities for work like this in anime, or in any pop culture, are precious few and come years in between. I count myself very lucky in that I've been able to write essays on so many of the works that have touched me deeply, and been able to unpack so many thoughts about them, and discuss them with so many people. That is the real pleasure in writing criticism, and what draws people to the trade, even as it's ceased to be much of a career. The best critics can enrich the experiences of others, and if you have an opportunity to do that, it's the best feeling in the world.

Oliver asks:

This is a question regarding the negative stigma that a lot of people seem to associate with otaku that watch and enjoy anime. I'm wondering why do such negative feelings exist? Why is it "wrong" to be a genuine fan of Japanese culture, yet there's seemingly nothing wrong with being interested in, say, Chinese or Korean culture? The terms "weeaboo" and "wapanese" get thrown around a lot too. In your opinion, what's the difference between being a weeaboo and someone who actively studies to learn Japanese and the culture?

This all comes down to one of life's great, basic truisms, and it is this: Nobody cares what you're into. Nobody. They only care if you're annoying about it and constantly shoving it in their face. At that point you become annoying and need to shut up and sit down.

Nobody cares if you're into Japanese culture, Korean dramas or Bollywood movies. Nobody cares if you're into violent furry incest porn, first-person shooters, or painting calligraphy of literary quotes on your living room wall. Seriously. Nobody gives a crap one way or the other.

The problems arise when you WON'T SHUT UP ABOUT IT and annoy the hell out of people. When you won't stop talking in a language nobody around you understands, call attention to yourself, talk crap about the tastes of everybody around you because they're into that totally lame and boring American stuff. When you can't stop talking about how someday you're going to move to Japan because it's so much better there, and you're totally going to marry a high school girl and learn martial arts and start drift racing because EVERYBODY in Japan does that. When you won't stop talking about how hot Japanese girls are because they all have exotic features and yet are all gentle and subservient.

See, nearly everybody is just fine with you liking anime and Japanese food and Shinto mythology. Nobody will judge you for watching Kurosawa movies or taking up a martial art. But people get more than a little irritated when you started wearing Naruto headbands to church, or you insist on eating spaghetti with chopsticks, or you yell at people in the handful of broken Japanese phrases you picked up from Bleach. People tend to not respond very well if you incessantly play them J-pop songs they clearly hate every time they're in your car, if you start using a high-pitched squeeky "cute" voice and glomping people, or start bowing to people for no reason.

Now, I'll bet at least a handful of the things I've listed above sound familiar. That's because people do them. A lot. Heck, even *I* did a few of those things when I was a teenager. Anime, manga, and fandom have introduced millions of young people to the world of Japanese culture, far moreso than most other countries, and that's great. The problem is that when you're that young and your worldview is that narrow, the abstract foreignness becomes the obsession, rather than the actual culture, and that becomes the vehicle for immature acting out. Unfortunately, there's enough of these specimens out there that they now have a name and a reputation, And I found at least 10 Tumblr pages and a subreddit dedicated to horror stories of their behavior.

Being into Japanese stuff by itself isn't the problem, it's the special hell that results when the Japanese fixation combines with obnoxiousness, immaturity and ignorance that makes a weeaboo. And THAT'S why those people suck. And they're EVERYWHERE. I can imagine that if you're not into any of this stuff, and your sole experiences have been through these human disasters, you'd be suspicious of anyone brandishing a Crunchyroll subscription. Normal people who are into Japanese stuff might get lumped in with them initially, but if you're actually a socially functional person I'm sure you can find ways of overcoming the stereotype.

And that's all for this week! Got questions for me? Send them in! The e-mail address, as always, is answerman (at!) animenewsnetwork.com.

Justin Sevakis is the founder of Anime News Network, and owner of the video production company MediaOCD. You can follow him on Twitter at @worldofcrap, and check out his bi-weekly column on obscure old stuff, Pile of Shame.

discuss this in the forum (177 posts) |