Isao Takahata: Endless Memories

Part I: Prehistory

by Mike Toole,

Part I: Prehistory

On May 15th, there was a farewell ceremony at the Studio Ghibli museum for the great genius Isao Takahata, the director who gave us films like Pom Poko and Gauche the Cellist and The Tale of Princess Kaguya. At first, I tried to ignore reports from the ceremony, including comments from Takahata's friend and colleague Hayao Miyazaki. Images from the ceremony showed a clearly upset Miyazaki, and it struck me as a little tacky to take the great director's grief and throw it out there to the public. But curiosity eventually got the better of me, and I'm glad it did—in his remarks, Miyazaki talked of his and Takahata's very first meeting in 1963, when the older Takahata approached the younger Miyazaki at the bus stop.

Think about that: for how many people in your life can you recall the very first meeting? Isao Takahata had clearly had a profound effect on his friend Miyazaki, as he had on us all. I want to return to the time of that meeting. See, when an artist of Takahata's stature passes away, there's a tendency to reflect on their artist's later period, when their style was clearly defined. We did that with Satoshi Kon, because that happened to be when he made his best works. But Isao Takahata's formative films are what consistently bring me the most joy, and those are the works that happened not all too long after that fateful meeting at the bus stop.

Let's wind the clock all the way back to 1955, which is when the above photo was taken. Takahata (second from the right) was wrapping up high school and getting ready to go to the University of Tokyo, where he'd study French literature. It was at this point that he encountered a film that would deeply affect him and awaken a burning curiosity about animation—a film called The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep. This movie was the creation of French animation legend Paul Grimault, working together with storied playwright (and a college favorite of Takahata's) Jacques Prevert. The product of their labor was an odd, halting thing—a whimsical fantasy film about the titular characters teaming up with a smart-mouthed mockingbird to defeat a vain and dastardly king. Work on the film started in 1949, but it was seized by producer Andre Sarrut when the studio ran out of funds. The movie was finished without Grimault's involvement and released to cinemas in 1952.

The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep had a profound and lasting impact on the young Takahata. Bernard Fiévé's stunning background paintings imparted the movie with a weird stream of hyper-realism, making the steps down from the villainous king's high castle seem so much like the steps leading to Montmarte. The characters and settings were fantastic, but frequently moved realistically, and Prevert's snappy and sophisticated dialogue was full of humor and gravitas. The whole thing felt literary, in a way that other cartoon features had not. This fusion of literature and animation is something that Takahata would pursue for the whole of his career.

Isao Takahata graduated college and started at Toei in 1959. He wanted to work in animation, but he had one problem—not only did he lack an artistic background, he really couldn't draw at all. But this was OK—Toei needed plenty of other creative staff, including scriptwriters, managers, and production runners. Takahata's first major project was assisting the director of the film Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon. After several successful outings using a classy, refined visual style courtesy of director Taiji Yabushita, it was time to change things up. Yugo Serikawa, a director with a film school background, was brought over from Shin-Toho to direct the new movie, bringing his broader expertise in film production with him. Designer Reiji Koyama introduced a super-flat, planar style, and most importantly, the animation director system was formalized.

Nowadays, the AD system, in which a supervising animator checks and corrects each frame of animation to ensure visual consistency, is old hat. But before Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon, the animation cleanup process at Toei had been defined almost entirely by an informal, two-pronged approach by the studio's best animators, Yasuji Mori and Akira Daikubara. Naturally, Mori would be the first credited animation director. As for Takahata, he didn't have the background to supervise the animation itself—that was taken care of by Serikawa's other assistant, Kimio Yabuki—but he proved unusually good at scrutinizing the film's storyboards, and then calling animation meetings in order to divvy up assignments amongst the staff. Turns out he'd been learning from the best—animator Yasuo Otsuka had recognized Takahata's drive and talent early, and took him under his wing. It makes a certain kind of sense that the first real supervisory role for the young Takahata, the future non-animator director, was under Yugo Serikawa, another future anime great with a non-animation background.

From there, it was just a deft sideways hop into the director's chair for Takahata on Toei's first anime TV series, 1963's Ken the Wolf Boy. Of course, Takahata only directed certain episodes of Ken, a surprisingly clever, sanguine Jungle Book knockoff. This isn't just because Takahata lacked experience-- the show's production was a bit chaotic. There was no chief director, and the staff was heavy with ace animators taking a break between Toei's more expansive theatrical films. The end result, at least in the case of the Takahata episodes I've seen, is energetic, weird, and surprisingly funny. One interesting side note: the animators created way more actual animation than competing shows from Mushi Production, whose corner-cutting approach would come to define TV anime. This over-production is something else that comes up over and over in Takahata's career.

Here, we come to Takahata approaching Miyazaki at the bus stop. This wasn't simply a matter of building fraternity—Toei's labor union was broken. There were the usual problems, like overwork and poor wages, but the studio execs had gained a foothold with union leadership and were using it to hassle workers that were deemed difficult. As a result, the studio was losing talented animators like Gisaburo Sugii, Taku Sugiyama, and a kid named Hayashi (who'd later change his name to Rintaro) to Mushi Production, which promised higher wages and a chance to work for the famous Osamu Tezuka. Takahata aimed to fix this, and he needed Miyazaki's help. The older man was a bit shy; meanwhile, Miyazaki was articulate and opinionated, and had a good reputation with the animators. The approach paid off—after winning concessions through a successful work stoppage in 1964, Miyazaki was elected secretary of the labor union, and by the time Takahata got started on his next movie in 1965, he himself was the union vice-chairman.

That 1965 production, Horus: Prince of the Sun, is Isao Takahata's masterpiece. It's an expressive and beautiful adventure movie, a complex tale with drama, romance, humor, and tough moral questions created in a time when even the most lavish and ambitious Japanese animation tended to consist of silly adventure stories. The movie was also almost Takahata's downfall; the union stopped work twice during production, turning what was supposed to be an 8-month project into one that lasted over two years. The studio boldly interfered, insisting that the original story's depiction of Ainu culture be moved to a safer, more Nordic-looking setting. Several minutes of the movie had to be discarded, unfinished. Two segments weren't finished but had to be included in the film anyway, and when it was all over, Toei yanked Horus out of theaters after just ten days, declaring it a failure.

But in some ways, this adversity only proved to make Horus a better film. During production, the movie's narrative transformed from a simple hero's journey to the story of common people banding together and rising up against the tyrant Grunwald, depicted in Yasuo Otsuka's storyboard above. Takahata leveraged this atmosphere, as well as the work stoppage, to unite the animation staff, both stoking their enthusiasm for completing the challenging film and urging them to stick together in opposition to the studio's stodginess. The movie itself remains an absolute marvel, an early showcase for animation geniuses like Miyazaki, Reiko Okuyama, and Yoichi Kotabe. The film's cold opening, depicting the title character savagely fighting off a pack of wolves with nothing but a hatchet, is one of the finest in the medium, featuring wildly expressive (and largely uncorrected) animation by Yasuo Otsuka. Takahata also divided the work up collaboratively, assigning different characters to each individual animator. Part of what makes the film so memorable is the delicate range of expressions of Hilda teased out by her animator Yasuji Mori. She's one of the film's antagonists, a girl who struggles to find the good within herself. Nowadays, Studio Ghibli is praised for its tough, complex heroines, but at the time, there was no one like Hilda.

Ultimately, Horus's adversity helped to transform the movie, which had been pitched to Toei as an ambitious fairy tale, into a strident protest film. The company may have disparaged it and the public initially missed out, but college students and the emerging first wave of anime hobbyists latched onto the film and wouldn't let it drift entirely out of fan consciousness. Late in the 70s, a young man named Toshio Suzuki was tasked with launching a new anime magazine, Animage; he envisioned the publication's first major production story being all about Horus, and asked Takahata and Miyazaki to speak about their film. The men declined, but the encounter nevertheless started a convivial relationship with Suzuki, who would join them at Studio Ghibli years later.

After Horus faceplanted in 1968, Takahata was demoted to TV work. He had plenty to do, including a lengthy run directing episodes of Moretsu Ataro, but it was made clear by studio chief Hiroshi Okawa that the director would not be getting another feature film at Toei. At this point, though, the band of crazies who'd spent the 1960s doing amazing work at Toei was starting to break up. There was the aforementioned slow exodus to Mushi Production by folks like Sadao Tsukioka; additionally, Yasuji Mori eventually split for a company called Zuiyo Eizo. In the meantime, Yasuo Otsuka left for Daikichiro Kusube 's new studio A Production, where he found notable success creating the first Moomin anime. He invited Takahata, Miyazaki, and Kotabe to join him there, to work on a new project: Pippi Longstocking!

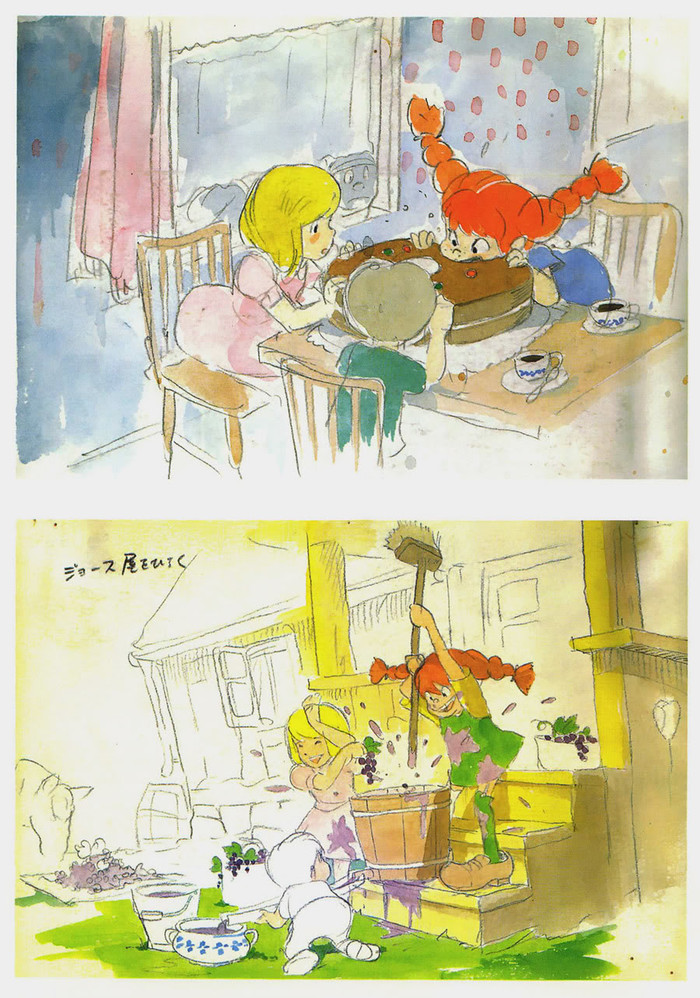

The trio took a whirlwind trip to Sweden to meet with Pippi creator Astrid Lindgren, but the meeting never quite came together, and neither did the Pippi anime project. Miyazaki, who'd taken the attitude that the project just had to succeed and created a ton of pre-production artwork as a result, was a bit crestfallen, but Otsuka had found work for the team – Tokyo Movie needed help rescuing their Lupin the 3rd TV series. Director Masaaki Osumi had taken Monkey Punch's freewheeling, breezy caper about a globe-trotting thief and focused on hard-boiled criminal antics, with Lupin and his gang gunning down crooks and fighting against murderous adversaries. This approach, while fresh and sophisticated, wasn't working for TV audiences, so Takahata and Miyazaki were brought aboard to brighten things up. Their rescue wasn't 100% successful—the series was still canceled after 23 episodes—but they did succeed in both creating a bunch of memorable, hilarious, and stylish episodes and solidifying the idea of the Lupin gang in the minds of the public.

In that same year of 1972, the Chinese government gave the Tokyo Zoo a pair of pandas, and inspiration struck Takahata: he'd use the stack of Pippi Longstocking pre-production materials whipped up by Miyazaki, including the character design of a precocious little girl with flaming red pigtails, to create an adventure involving pandas. The public's fascination with pandas was strong enough to elicit not one but two short films about little Pippi er, I mean, Mimiko, and her adventures with an adorable father-and-son panda duo.

There's another bit of storyboard by Yasuo Otsuka. It's a huge pain in the ass to find storyboard frames actually drawn by Takahata online, because he seldom did them; he always had a co-pilot to handle the visuals, whether it was Miyazaki or Otsuka or Osamu Tanabe or Yoshiyuki Momose. Panda Go Panda might have ultimately been forgotten without Takahata and Miyazaki's involvement (Panda's Great Adventure, Toei's answer to panda-mania, certainly was, despite Yugo Serikawa and Yasuji Mori's fine work on the film), but it's good that it wasn't. Like Horus, it's a film that touches on the fantastical – a little girl living on her own, with loveable talking pandas?!—yet is imbued with a rare sense of weight and realism. This is something Takahata carefully refined for his entire career. For him, it just wasn't enough to make characters who looked cool doing interesting stuff; he had to put them in settings that felt every bit as complete and detailed, and ensure that his animators had them move realistically. Mimiko goes on some fun adventures with the pandas, but for me the best parts of Panda Go Panda are in the opening, just showing the child Mimiko walking around town, buying groceries, and setting up house. The dad panda is also an obvious early precursor to Totoro in the way he moves and talks, something played up hilariously in the English dub, produced decades later. Dub fans laud the late Animaze founder Kevin Seymour as brilliant in terms of casting and adaptation, but here he turns in a delightfully weird performance as the big round panda papa.

The approach to making the ill-fated Pippi was replicated for 1974's Heidi, Girl of the Alps, Takahata's first big TV project for Zuiyo Eizo, where he was reunited with his colleague Mori. Once again, Miyazaki and Takahata jumped in a plane and flew halfway around the world, this time to Switzerland, where they spent days taking pictures of sheep and cows. For Takahata, this was crucial—he couldn't just get some photo references of the Alps and have his team draw cartoons of a little girl running around them, he had to depict the wholeness of a culture, to capture something elusive and essential about how the people lived. It also helped that Heidi creator Johanna Spyri hadn't been alive for the better part of a century, and therefore couldn't decline to take meetings with him.

Heidi was a game-changer. First of all, Takahata's approach to directing—making characters act naturally, seeking out feedback from animators to create his works collaboratively, with the notion of augmenting and sharpening his own vision by combining talents—reached its heights here. Pretty much every episode is bursting with color and liveliness. Because of this, Heidi was a major hit on TV. This was sort of a problem for rival producer Yoshinobu Nishizaki, who really needed his Space Battleship Yamato to be a big hit. Yamato did well, but it simply could not beat Heidi, which siphoned viewers away by the thousands, hit #1 in its timeslot, and got featured on the cover of TV Guide. In particular, Heidi was a huge hit with young girls; the magnetism of Heidi and her pals Peter and Clara proved irresistible. There had been anime made for girls before Heidi, but Heidi was proof that anime for girls could be a top draw.

The second way that Heidi changed everything was in the introduction of a new system for creating and correcting animation. Up until then, anime would start to take shape via the storyboard.

Like I said, it's a pain in the ass to find Takahata's own storyboards, so here's one by another great director who kinda sucks at drawing, Yoshiyuki Tomino. (Naturally, after doing the above storyboard for Space Battleship Yamato episode 4, Tomino came down the road to work on Heidi!) After the creation of the storyboards, the work would be handed out to the key animators, who'd create rough versions of the animation cuts. After correction and in-betweening, the animation was done and ready for color and photography to be handled. But there was one issue that kept tripping shows up: the storyboard wasn't always enough. If an animator didn't understand precisely what the director wanted from the storyboard, they could waste time creating a sequence that would then have to be heavily corrected, or worse, thrown out and reshot entirely. A more precise blueprint for the animators to work from was needed, and Miyazaki had the answer: layouts.

Here's a layout from Heidi. You better catch that goat, Peter! Layouts were essentially a more complete, detailed version of the storyboard; more than storyboard frames, but not quite keyframe animation unto themselves. They gave the animators a lot more to work from, and so the number of reshoots went down while the overall drawing quality ticked upwards. Being a new process, only Miyazaki really understood what was needed to create the show's layouts, so he drew them all himself: thousands and thousands of them!

This made Heidi awesome, a show that was warm, gorgeous, and effusively naturalistic in a way that no TV anime before it had been. It also made Heidi utterly overcooked; Miyazaki's feat of drawing every layout himself was obviously completely impossible to reproduce. Nearly every TV anime since Heidi has employed layouts in some form or another, but none has had the sheer level of craftsmanship on display. The show's lavishness also put its production company, Zuiyo Eizo, in jeopardy, such that a savvy business manager needed to be called in to rescue the ailing operation. Enter Yoshinobu Nishizaki—yep, the Space Battleship Yamato guy!—who solved the money issues by transforming Zuiyo Eizo into a holding company and creating a new company—Nippon Animation—to handle the animation for new TV projects like Dog of Flanders.

While Heidi was an unqualified success for Takahata, it had the unfortunate side-effect of leaving Miyazaki lastingly bitter about TV anime. He still had it in him to work on TV, like his superb Future Boy Conan. But he always complained vociferously about how pitiless and relentless the TV anime business was, working staff to the bone for meager wages and demanding an endless repetition of similar shows that would be gobbled up and quickly forgotten about by uncaring mass audiences. In Heidi's case, at least, he was wrong about that last bit—rarely does a year go by without some anime or another referencing Heidi's iconic scenes.

Still, for a time, Takahata and Miyazaki stayed on the Nippon Animation beat. Takahata followed Heidi with Marco: From the Apennines to the Andes, another 52-episode literary jaunt about a good-natured, working class kid from Genoa cross-crossing the mountains, following his mother from Italy all the way to Buenos Aires, Argentina. Marco wasn't the huge hit that Heidi was, but it's still thrillingly vivid, a solidly entertaining series. This time, Takahata's problem was that he wasn't able to use Miyazaki as animation director – the guy was just too busy drawing layouts! Fortunately, the husband and wife duo of Yoichi Kotabe and Reiko Okuyama were available to step in. Okuyama, in particular, was renowned for her ability to create absolutely meticulous keyframes, ones that almost never required correction, so Marco's visual luster held up.

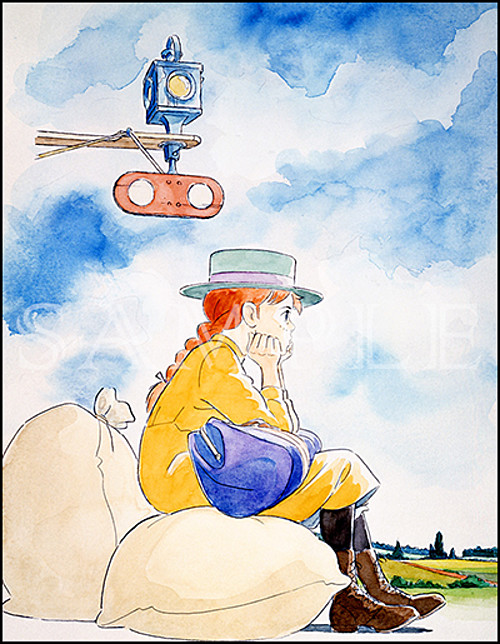

It was then, in 1979, that Isao Takahata created his masterpiece. Yes, Horus and Heidi were also his masterpieces. The guy made three masterpieces, alright? This time, another research trip was required, so Takahata jumped in a plane and flew halfway around the world to Prince Edward Island. The goal: faithfully recreating a vision of Canada at the turn of the 20th century! It was all in service of creating a version of Lucy Maud Montgomery's Anne of Green Gables. And man, as great as Heidi is, and as pivotal as it was in introducing the layout system, Anne of Green Gables eclipses it.

Maybe it's because the challenge for Takahata and his team was a little greater. After all, making a warm and wonderful version of Heidi still starts with depicting an irrepressible little girl who makes friends in one of the most beautiful regions in the world. Anne of Green Gables, on the other hand, opens with a pallid, motormouthed little scamp in threadbare clothes, obliged to help out a pair of aging farmers in a small island village. But via a series of simple visual flourishes in the first episode alone, Takahata sells the idea that this unmoored young girl is able to charm her way into the lives of her wards the Cuthberts.

That's just the start—Montgomery's Anne charts the title character's growth from an earnest kid into a hardy would-be schoolteacher. What Takahata needed to do for this series wasn't just his usual approach of marrying literature to animation, and carefully depicting the largely unseen magic of normal people going about their lives—he had to show the passage of time, of Anne and her friends growing up. The magic wouldn't quite work if he couldn't depict Anne's transformation from an ingratiating and charming kid into a pretty and driven young woman. Fortunately, his character designer on the series, Yoshifumi Kondo, was up to the task. Miyazaki was also on hand to help out, but ended up leaving before the series was finished to work on The Castle of Cagliostro. “I don't like that Anne,” Miyazaki reportedly wrote in an amusing farewell note, “Well… give her my best!”

What Takahata gave us in Anne of Green Gables, his last big TV project, is a series full of small character moments, simple visual and musical flourishes that have immense power. You can put the show next to Tomorrow's Joe as a 1970s TV anime series that has aged extraordinarily well. It's always been a point of frustration for me that Anne, a series based on books written in English, was never available dubbed in English, but an English version produced in South Africa has recently come to light. It's a sheer delight to see Takahata's Anne of Green Gables in the language in which the book was written, South African accents and all. I hope that this version becomes more widely available.

Here, we come to the end of Takahata's early and middle period. By this point, the old band was well and truly broken up. Miyazaki was long since ready to direct his own works. Mori hung around Nippon Animation, occasionally working for other studios. Otsuka kept doing his own thing, whether it was at A-Pro or Shin-Ei or Telecom Animation; while Okuyama pursued her own projects, her husband Kotabe soon split for Nintendo. It would soon be time for Takahata to take his talents back to the big screen, but he spent the 70s refining the most important elements of his approach to filmmaking. So many of these works spend time carefully depicting the characters just going about their daily lives, cooking and cleaning and getting dressed and doing chores and talking to each other and going places and forming relationships. You won't notice this magic, not right away, but it's there—and it's where Isao Takahata's greatest strength lives on.

Isao Takahata: Endless Memories is a week-long series, of which this is Part II. Join us tomorrow for an in-depth look at two of Takahata's early films, Chie the Brat and Gauche the Cellist, by Andrew Osmond.

discuss this in the forum (61 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history

back to Isao Takahata: Endless Memories

Feature homepage / archives