Isao Takahata: Endless Memories

Part II: Chie the Brat and Gauche the Cellist

by Andrew Osmond,

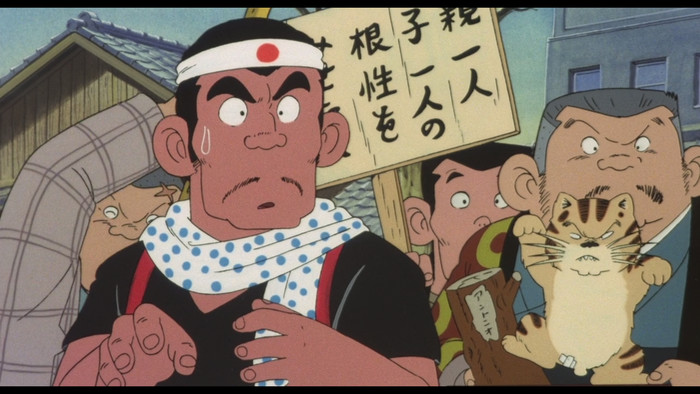

“After producing a classic like Heidi, how can you now do a film about a girl cooking giblets on skid row in Osaka?” Isao Takahata was asked that by a rude young journalist called Toshio Suzuki – yes, that Toshio Suzuki. At this time, the future head of Studio Ghibli was the editor of Animage, trying to get the lowdown of why Takahata, the director of charming, inoffensive Sunday TV fare like Heidi and Anne of Green Gables, was directing a broad blue-collar comedy, Chie the Brat (sometimes referred to by its Japanese name, Jarinko Chie).

Suzuki's description of Chie is fair. Released in 1981 and based on a manga by Etsumi Haruki, it's a skid row film, where people drink and gamble and brawl, and kids like Chie grow up sly and street smart, without time to dream of Alps or fairies. But Chie's neither brattish nor bad – she's actually a great kid, and as much the hero of her story as Heidi or Anne before her. Still, her film is an earthy comedy. One of the best visual gags involves runny, dripping snot, and there's a load of jokes about tomcat testes, linking Chie to the director's Ghibli work. We trust you recall the incredible magic gonads of Pom Poko.

True, it's a shock if you're expecting the Takahata of Heidi or Anne. Quite possibly Chie reflected Takahata's need for change, after spending years depicting cute WMT kids in far-off pastures. In contrast, Chie was his chance to depict urban Japan in its colourful smelliness and scuzziness. Given Takahata's interest in world animation, he may have taken note of the American films by Ralph Bakshi (Fritz the Cat, Heavy Traffic), which also celebrated blue-collar downtown.

Takahata may have also been yearning to do something irresponsible, something funny, like his Lupin TV stint at the start of the '70s. In a making-of film for Only Yesterday, Takahata stressed how much he liked making people laugh, and suggested that he only moved into sombre, Fireflies fare to distinguish himself from Miyazaki. Takahata wasn't an animator, but he may have been swung into doing Chie by two animator friends, Lupin veteran Yasuo Ōtsuka and Horus designer Yōichi Kotabe, who realised how much fun Chie could be animated. Otsuka and Kotabe are jointly credited as Chie's animation directors and character designers.

Chie's basic situation, though, is far from funny. She lives with her hopeless dad Tetsu, an incorrigible foul-mouthed gambler, brawler and slacker, and his two parents, who despair of Tetsu as much as Chie does. Aged about ten, Chie often holds fort in her dad's restaurant, grilling, serving and collecting money, and taking no nonsense from the tispsy adult clientele. If you thought the child labour was strenuous in Spirited Away or Kiki, Chie's working on another level. It's Chie's awesome resourcefulness, her fearlessness, which stops this from being a terribly grim situation. When two boys harangue her about her low school marks – she's far too busy working to study - she confronts them with a huge stick. When a boy sneers that she wouldn't dare use it, she bashes him without hesitation. In short, Chie can handle herself on Osaka's mean streets. It's only when she secretly spends a day with her mother, currently separated from her dad, that we see her different side – she dons a pretty dress, and looks at her mum with an adoration she shows no-one else.

Chie is pointedly drawn as strong not pretty, in line with anime like Lupin that prioritise funny, ungainly, even grotesque designs. (Chie's animation was by Lupin's studio, Tokyo Movie Shinsha.) Many of the characters, including Chie herself, sport big uneven teeth; they recall the characters in other contemporary anime, such as Miyazaki's TV Future Boy Conan (designed by Otsuka) and the “Mujaki” adversary in the Urusei Yatsura film Beautiful Dreamer. Chie's cartoon designs don't hamper the careful life observation which would later inform Ghibli. There's the animation of Chie preparing food in the restaurant, or of people eating or drinking inelegantly. Frequent pillow shots of trains running past the neighborhood anticipate another real-world comedy, the anime Maison Ikkoku.

As usual for a Takahata film, Chie has an episodic story, though it's more straightforward than much of his Ghibli work. One of the funniest early scenes has Chie's dad Tetsu barging into a parents' day at her school, reducing her math class to chaos. (Like Taeko in Only Yesterday, Chie hates doing fractions). Of the film's two main plotlines, one involves Chie's relationship with her mother, and Chie's hope that they can live together again. The other, much more cartoonish strand has cats; Chie adopts a stray who acts as her bodyguard and beats up the top cat of her neighborhood's crimelord.

In fact these two plotlines are related, as they're both comments on masculinity. The cat plot is an extended joke about castration; Chie's cat defeats the gangster's one by severing one of its furry testicles. When the said testicle is dug up later, it's turned into a forlorn golden ball, playing on the Japanese word kintama. There may also be a subtle joke in an unrelated scene where Colonel Bogey is heard on the soundtrack; that's the tune better known as “Hitler has only got one ball.”

After the fateful severance, the castrated cat's owner transforms from a thug into a kind, gentle, tender-hearted restaurant owner. This storyline culminates with a new vengeful cat coming on the scene, and a feline fight presented as a Western shootout, cats bearing their balls like gunslingers' holsters. The crisis is only resolved when one cat refuses to be macho. The cat fight itself is superbly animated, and a plausible influence on a farcical punch-up at the end of Miyazaki's Porco Rosso, which makes a similar point about movie-style machismo.

As for Chie's human plotline, it's made clear that Tetsu wants her daughter to be a boy. At one point, Chie plays with increasingly hilarious hairstyles in front of a mirror at home, until Tetsu freaks out that she's not being her usual tomboy self. Later Tetsu orchestrates the cat fights of the climax, just to get back to the violence that he knows. While some other characters in the film are confident that they can solve the family's problems, and get Tetsu back together with his soft-spoken wife, Takahata shows succinctly that such a Hollywood-style fix won't last. Things may improve or decline, but Chie's family problems are fundamentally unsolved at the end.

Chie is vastly interesting, but – here's the kicker – it's not massively funny, nor is it solidly engaging. It's unusual in focusing on socially marginal characters, but so would Satoshi Kon's Tokyo Godfathers, a film that's as serious as Chie and far funnier. Chie is like some later Takahata films in that it makes greater sense on reflection than it does while you're watching it. For instance, its last scenes suddenly switch from exploring Chie's family issues to the cat-fight climax; there are connecting themes, but the dramatic gear-shift is just baffling to the viewer. Perhaps Takahata realised this himself. He would later make Only Yesterday, a much artier film about another young Japanese girl, which goes out of its way to highlight the huge, disorienting contrasts between its different story strands.

Chie is most impressive for its inspired title character, and for being as fearless as Chie in poking themes that are no less contentious now than they were in 1981. And for Takahata himself, Chie marked an inadvertent turning point in his work. Before Chie, almost none of his signature anime had been set in Japan. From Chie until Takahata's last film, Princess Kaguya, they all would be, including a TV series version of Chie that would run into 1983.

GAUCHE THE CELLIST

The film Gauche the Cellist was released in 1982, only a year after Chie, but it shows a very different side of Takahata. To go from Chie to Gauche is to go from urban knockabout to rural lyricism, but unlike Takahata's World Masterpiece Theater series, Gauche revels in the lyricism of the Japanese countryside, six years before Miyazaki would in Totoro. Reportedly Gauche was six years in the making, which would suggest Takahata embarked on it around the time he was making Marco on TV. This kind of claim can be wrong or misleading - Takahata himself said Kaguya's actual production took four years, not the eight claimed in media reports – but it seems plausible in Gauche's case.

The reason is that Gauche was a ‘labour of love’ production, though it was made by a commercial studio, Oh production. At just over an hour, the film may seem short, but according to anime expert Ben Ettinger, it was largely the work of just two artists. They were Takamura Mukuo, who drew all Gauche's backgrounds, and an artist who's referred to in different sources as either Shunji Saida or Toshitsugu Saida; he drew all the key animation, albeit with a big team of in-betweeners. Saida had contributed to Takahata's Marco, Anne and Chie, and would go on to Fireflies and the Takahata-esque Mai Mai Miracle.

Gauche is a fairy story, and like Kaguya, you can watch it and ‘hear’ the underlying tale as if it's being read to you aloud (at bedtime surely), by an excellent storyteller. It's set in a prewar Japan, around the start of the Showa era – we glimpse an automobile, and there's one lovely scene in an early, ‘silent’ film cinema. The source story was published in 1934, following the death of its author Kenji Miyazawa (Night on the Galactic Railroad).

Gauche plays in an orchestra which is practicing Beethoven's Symphony No. 6, aka the Pastoral Symphony. This is one of the most familiar works of classical music worldwide and Gauche, as we'll see, feels like a consciously “international” animation, unlike the proudly local Chie. The conductor chides Gauche for being the orchestra's weak link, whose sub-standard playing drags down everyone else. Gauche returns sorrowfully to his simple country cottage to practice – he lives alone, and the film gives him no backstory.

Over the next nights, Gauche has four visits – from a cat, a cuckoo, a tanuki and lastly a mother mouse nursing her ailing child. Each of these drop-ins prompts him to play, in performances that sometimes become duets, letting Gauche hear the music in, for example, a cuckoo's call. Music, the film suggests, is the art that brings humans closest to birds and animals; in recognizing this relation, Gauche becomes a better musician and a kinder person. We hear a lot of Beethoven, but also the music of nature. For instance, the film starts with the chirp of summer cicadas before the orchestra starts.

Music is also a huge part of animation history. An early dream scene, where Gauche's orchestra is lifted into the air by the storm, while the musicians keep playing their instruments, can't help but recall Disney's 1935 cartoon The Band Concert. Beethoven's Pastoral was itself animated in a long section of Disney's Fantasia. But Gauche doesn't feel Disneyesque. It has funny cartoon gags, but even they have un-Disney dignity. The finest is a sequence where Gauche's first visitor, the cat – who's by far the best animated character in the film - hates the atonal music he plays, but still finds itself dancing helplessly to it, twisted and yanked around like the luckless girl in 'The Red Shoes.'

Yet the animals are treated with dignity too. The cat aside, they're solemn and serious, which is itself often funny visually (especially the appearance of the grave-faced tanuki, who looks like a pint-sized teddy). A lot of the other humor comes from Gauche's arguments with these creatures. He doesn't react with wonder when they talk to him, but rather with perplexity and irritation, like Alice in Alice in Wonderland. There's no excess syrup in the film, not even the kind you might expect, like a friendly voice-over narration or a little tune for each animal.

Gauche feels less like Disney than like two poetic fairy tale cartoons that Takahata and Miyazaki had loved as youngsters; France's The Shepherdess and the Sweep (later revised as The King and the mockingbird) and Russia's 1957 The Snow Queen. Additionally, Gauche's most poignant scene, in which a mother mouse begs the cellist to help her sick baby, strangely parallels another cartoon film that was released in 1982 – not an anime but Don Bluth's Disney-challenging The Secret of NIMH, though neither could have influenced the other.

Gauche's animation is very attractive – indeed, some of the creature animation is exquisite, though Gauche himself doesn't have the expressive depth of the protagonists in Fireflies or Kaguya. However, he's lent a substantial extra dimension by his outline, which is drawn thickly, furry and bristling, especially when he's playing. Decades later, Takahata would take this aesthetic to extremes when he made Kaguya. According to Suzuki's recently translated book Mixing Work with Pleasure, the director became obsessed with the lightness or darkness of lines, their width, the beginnings and ends of brushstrokes… which all helps to explain why Kaguya took so long to make. Gauche is a delightful film, completely suitable for any age, and only slightly marred by an ending that seems to run a few minutes too long. However, the protracted conclusion does feature the only traditional (human) Japanese music we hear in the film. Perhaps Takahata thought Gauche needed it to balance out the Beethoven.

Isao Takahata: Endless Memories is a 7-part series; we'll return on Monday, August 6th with a piece on what might still be Takahata's best-known work to Western audiences, Grave of the Fireflies.

discuss this in the forum (61 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history

back to Isao Takahata: Endless Memories

Feature homepage / archives