Precure's Henshin Hero Heritage

by Raffael Coronelli,Japanese pop culture melds across its various mediums on a regular basis, but there's one magical girl anime franchise that takes its rip-roaring live-action influences to a level that has translated to multiple decades of unprecedented success. It's an exhilarating combination of cute and fierce ingredients in an ever-shifting recipe, a franchise that exists as a subgenre unto itself.

Precure, short for “Pretty Cure,” has been a yearly juggernaut in the anime industry since 2004, thriving on its ever-evolving distillation of the “magical girl” concept into a high-octane show that draws heavily from styles and traditions of a different entertainment medium altogether. Let's look at how a form of media known more for Godzilla movies than magical girls has influenced one of the most popular anime franchises of all time and its hybridized pop culture footprint.

For the 2004 broadcasting year, Toei Animation needed a new TV series aimed at young girls at the behest of their Bandai toy advertising overlords. Sailor Moon had already brought the magical girl concept to soaring heights of popularity a decade prior, achieving classic status both at home and abroad. Ojamajo Doremi had been a more recent Toei magical girl show that helped create a hunger for more of the like at the studio. While successful and beloved, these series were put on ice by '04, and a band of Toei producers under the pseudonym “Izumi Todo”—though many attribute the core creative choices to one Takeshi Washio—decided a different approach was needed.

Tokusatsu (live-action special effects, or literally “special filming”) series Kamen Rider and Super Sentai have been titans of media and merchandising in Japan since the Toei Company launched them in the 1970s, and are textbook examples of how to create a veritable never-ending stream of bad-guy-pulverizing action that captures children's attention and keeps fans engaged for decades. It was the perfect template for a new kind of magic in a magical girl show.

Futari wa Precure, helmed by Dragon Ball director Daisuke Nishio, exploded onto Japanese televisions in the time slot just after Kamen Rider Blade. It sold itself on a very simple premise: what if two magical girls physically kicked the crap out of monsters and bad guys?

Magical girls in anime up to that point typically fought via casting spells and firing off sparkly projectiles. Nagisa and Honoka, Cure Black and Cure White, opted for a more direct approach—punch and kick the enemy and blow them to smithereens. Even their punishing Dual Aurora Wave finisher evoked a cross between Ultraman's Specium Beam and Goku's Kamehameha. Their non-magical personas—a swaggering tomboy jock with more insecurities than she lets on (drawn as the extended fist in the henshin sequence's “Ultraman rise”) and a scientifically-minded genius who struggles with getting her feelings across, backed up the series' non-traditional theme with engaging slice-of-life characterization.

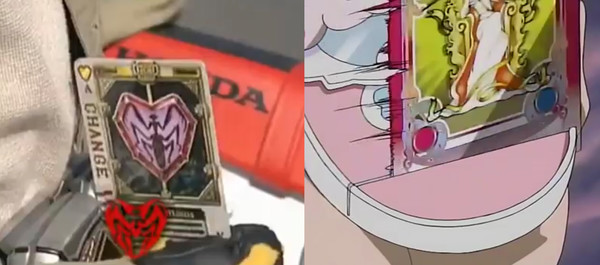

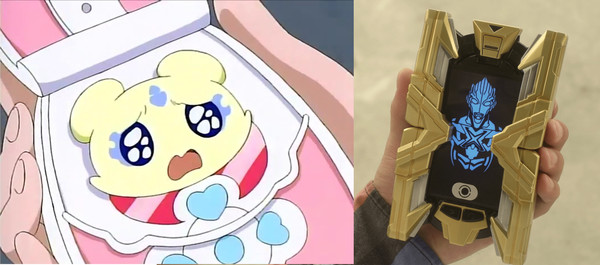

A noticeable element Precure brought right away from henshin hero tokusatsu was a more prominent and visceral henshin device, an inherited artifact that allows the protagonist to undergo a metamorphosis into their hero form. While items like Sailor Moon's iconic brooch kicked off previous magical girl transformations, Precure's feel more like a tokusatsu show with a toyetic central tool that, via playing with it, ignites a visually intense sequence where the girls “armor up” in their outfits. The original Futari wa girls used Card Communes, devices shaped like cellphones that read cards which naturally could be collected and used with the toy version—similar to Kamen Rider Blade's Blay Buckle.

As an original element, the Card Communes housed each of the Cures' fairy mascot companions like Tamagotchi. Variations on this have continued; Delicious Party Precure has the fairies transform their own bodies into food-shaped henshin devices. Enveloping the Cures in a colorful explosion of light energy, henshin sequences are a highlight of the shows' retina-blasting visuals.

One smash-hit series and a sequel season later, Precure tried its first reboot, Futari wa Precure: Splash Star. While the season is fondly remembered by fans on its own merits, it had two main characters with designs close to the original's Nagisa and Honoka. For wider audiences, the novelty had worn off. Precure was on the verge of petering out, as would've been reasonable for any other series to have done at that point.

That was when the producers, director Toshiaki Komura, and writer Yoshimi Narita decided to experiment. For the fourth season of Precure, they would once again reboot. Instead of two Cures with similar designs to the original series' iconic looks, there would be a roster of five girls who'd each transform into a different color-coded and themed fighter with unique abilities and attacks, together forming an interlocking team who would coordinate to defeat their enemies. If this sounds familiar, it's because the producers had once again reached across the way to the live-action studio and taken the core idea from Super Sentai, the series that most westerners have seen adapted as Power Rangers. The result was Yes! Precure 5, and it put the franchise back on the Japanese pop culture map for good. Like the ever-evolving Sentai teams, the girls' identities are variations on a rotating theme, whether it's fruits (Fresh Precure!) or sweets (KiraKira Precure a la Mode).

One of the least-discussed recurring elements is the driving force of the show's conflict. Precure is a giant monster series (sort of). While they aren't the main focus, strange giant monsters are manufactured by the main villains and sent out as corrupted minions to battle the Cures. The weekly kaiju formula was introduced to Japanese television by Ultra Q, though the sometimes absurd monsters sent by a puppeteering background villain are another device that feels closer to Super Sentai. Precure's mutant attackers range in threat and design from otherworldly abominations to a mutated version of the girls' English homework, with some incorporating mecha elements that shoot beams, missiles, and other projectiles at the girls. The monster fights' climaxes are in the Ultraman tradition, with a flashy finishing move causing the monster to revert in a colorful blast to a non threatening form or, in the case of especially merciless shows like Delicious Party Precure, violently explode.

While all these cross-medium similarities exist, the fact remains that Precure is an animated series and the Cures exist only in drawn form—or do they?

Live stage shows and character appearances are a major part of Ultraman and Super Sentai's interactions with their fans in Japan, so it only makes sense for Precure to follow suit in this regard. But how can anime characters exist in reality, and in this type of widely distributed setting? The answer is through animegao kigurumi, an immersive costume worn by an actress that consists not only of the character's outfit, but a head mask of the stylized anime character's face. In this sense, the Cures have “suit actresses” who appear onstage and in other types of in-person appearances for acrobatic performances like one would see from a tokusatsu suit actor. It still looks removed from reality, but it lends the Cures a physical presence outside the show that's usually reserved for live-action characters.

There have even been live events featuring Precure, Super Sentai, and Kamen Rider characters all at once advertising the hour-and-a-half time block the three inhabit together on Japanese television. The connection has endured behind the scenes as well; Cure Spicy voice actress Risa Shimizu said in an interview that she got into the type of hero shows of which Precure is a part through watching Choujin Sentai Jetman (1991) as a child.

As for the franchise's continued longevity, that can be attributed to the same way a franchise like Ultraman has survived for more than half a century: maintaining a delicate balance of comforting formula and inventive variety. Precure is free to switch up the flavors and be more or less anything whomever is in charge of the current season wants it to be—from Futari wa Precure to Tropical-Rouge! Precure's vaguely Hans Christian Andersen-inspired comedic fantasy about a club of middle school girls who've befriended a mermaid embroiled in an undersea conflict, directed by maverick animator Yutaka Tsuchida and with main series writer Masahiro Yokotani (who has co-writing credit on the screenplay for Godzilla, Mothra, and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters, All-Out Attack)—all while delivering on some variation of the tasty sugar rush that keeps people coming back. Rather than a continuing narrative or recurring characters as one would see in a manga-adapted series, the carried over elements are a set of ingrained tropes in the expansive, single-franchise Precure genre.

Inspired by animation and live-action, Precure has exerted its own legacy in both. Anime like the action-free PriPara and Kiratto PriChan magical idol series have taken influence from its incorporation of toyetic elements with extended song and dance routines taking the place that battle scenes occupy in the Precure formula. In a bit of reverse inspiration, tokusatsu series have adopted henshin devices with some familiar characteristics. Items like Ultraman X's cellphone-esque, card-reading, digital-Ultraman-housing X Devizer can trace a clear lineage to Futari wa Precure's Card Communes.

The duality of Precure's pop culture footprint lets it exist in its own realm. It draws so heavily from outside of traditional magical girl anime, while still fully being one of modern anime's pillar franchises in its home country and flagship representations of the magical girl concept, that it transcends categorization other than to say that it is itself. There isn't anything else in the world exactly like Precure.

Raffael Coronelli is the author of How to Have an Adventure in Northern Japan, Daikaiju Yuki, and other books, and has contributed essays to Blu-ray releases from Arrow Video. Follow: @raffleupagus

discuss this in the forum (6 posts) |