Why Creators Root For Akane-banashi

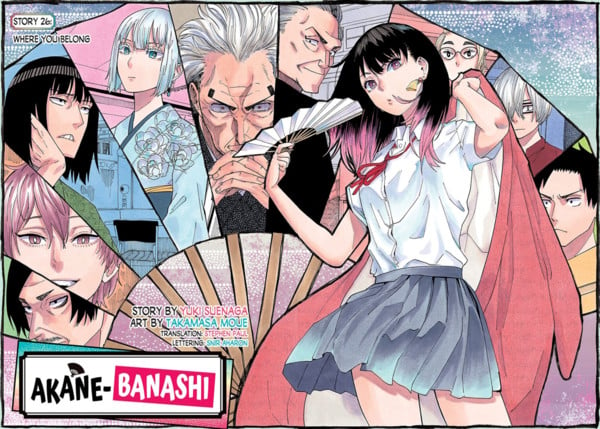

by Eric Bone,When an artist publicly endorses another artist's work, it can be easy to assume that that recommendation has to be partially motivated by some kind of aesthetic or thematic similarity to their own. Fans of One Piece, Evangelion, and Re:Zero likely made a similar assumption when they found out that their favorite creators were fans of Akane-banashi, a Shonen Jump manga created by Yūki Suenaga and Takamasa Moue about a comedic storytelling performance art called rakugo, but the manga itself is actually as different from those works as they are from each other. Rather than an appeal that is unique to Eiichiro Oda, Hideaki Anno, and Tappei Nagatsuki, Akane-banashi's novel approach to the challenges that come with a Shonen Jump debut naturally resonates with anyone who is passionate about storytelling.

Shonen Jump's extremely competitive lineup means that newly serialized manga have only a dozen or so chapters to capture readers' attention, and a manga about a niche subject like rakugo has to clear an even higher hurdle in order to survive. The standard solution to this problem is to include elements that get readers invested in the future of the manga, as a kind of insurance. An unsolved mystery or the promise of a future romance can act as a safety net in case readers lose interest in a manga's current storyline. Akane-banashi on the other hand—in spite of being the kind of manga that would seemingly be in most need of a specialized survival strategy—makes the bold decision to ignore the danger entirely. From early on it felt like a manga that was in its second or third year of serialization, or a highly anticipated second work from an established author, and that self-assured approach actually ends up contributing greatly to many of the overarching themes of Akane-banashi's story.

The manga's title is both a reference to the names of different types of rakugo stories (Ninjo-banashi, Zenza-banashi, etc.) and an apt description of the manga itself. Akane-banashi is structured just like a joke in that each arc creates an expectation that the story is heading one way, only for things to go in a completely different, more interesting direction. In the first chapter, Akane's father is expelled by the head of his Rakugo school, Issho Arakawa, after making tradition-breaking changes to a story. Akane makes it her goal to join that school and make Issho acknowledge the worth of her father's performance style, which naturally creates the expectation that, to some extent, Issho and his Arakawa school are Akane's opponent, representing the Rakugo world's rigid, arbitrary traditions, and that Akane's role is to overpower them with her skill as a performer.

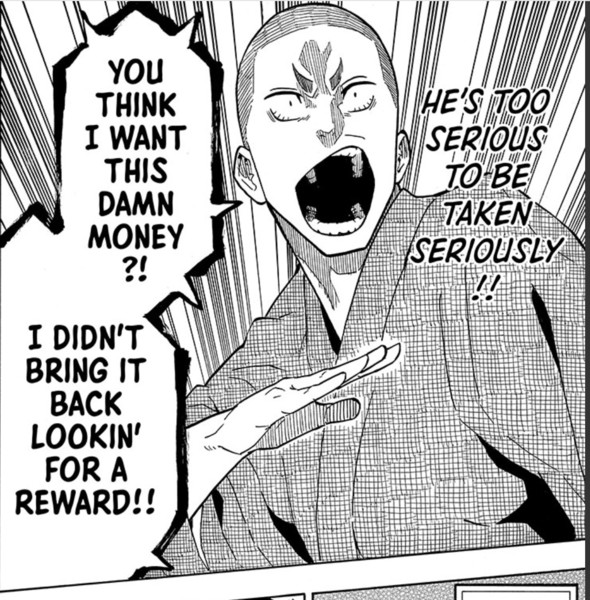

So when, in chapter 6, Akane is told by her very serious senior student, Kyoji, that low-ranking performers are supposed to do chores for their seniors in order to gain a considerate mindset called Kibataraki, his advice seems more like an obstacle than a lesson. In the “punchline” of the chapter, Akane's attempt at using an upcoming performance to show Kyoji that skill is all that matters fails and she receives her first ever lackluster response from an audience—in spite of seeming to do everything right. Kyoji tells her that her performance felt like she was throwing a 95 mph fastball that landed outside of the strike zone. Kyoji initially comes across as the kind of character that is “too serious” and follows the rules for their own sake, which in turn makes the concept of Kibataraki seem like an excuse that his excessive seriousness prevents him from seeing through. The kind of character Kyoji actually is, as well as the difference between “being too serious” and taking things seriously, are the primary focuses of Akane-banashi's Kibataraki arc.

In order to help her find her deficiencies as a performer, Kyoji sends Akane to an izakaya pub to work part-time. Like her earlier performance, Akane's approach to this job looks perfectly correct. She looks up customer service tips on the internet and puts 100% of her effort into their execution, but far from the overwhelming force of customer service excellence she intends to be, she spends her first day as deadweight for her coworkers and an annoyance to her customers. The things she does that look right on paper—such as greeting customers with plenty of energy (and volume) or giving detailed descriptions of the menu—fail to translate to a pleasant customer experience because she isn't behaving with their individual needs in mind. It isn't until she remembers Kyoji reprimanding her for not slowing the pace of her earlier Rakugo performance for a mostly older audience (and then an experience miming her way through an interaction with a customer from overseas forces her to think about the needs of person in front of her), that Akane finally begin to understand the value of Kibataraki.

Akane initial attempt at customer service is the kind of behavior that is often described as “taking things too seriously,” or “trying too hard,” but, like Kyoji's baseball analogy highlights, her actual mistake wasn't the amount of effort she put in—it was the direction she aimed it. In both her performance and her customer service, Akane was trying to do what felt like working hard, without considering the point of all her effort. This theme is cemented further when Akane finally gets a chance to see Kyoji perform and is immediately struck by the effect that his seriousness has on his performance. Kyoji carefully considers the effect that each element of his performance has on his audience and has a firm belief in the value of everything he does. He puts all of his energy into the small details of his performance, like his posture and gestures, and, as a result, is able to turn his seriousness into a trademark. He always fully commits to the bit and performs a kind of rakugo that Akane describes as “too serious to be taken seriously.”

If the job of a story is to explore interesting themes in an entertaining way, then the Kitabaraki arc is emblematic of Akane-banashi's pure approach to that task. The characters' behavior and every stage of the plot exist for the sole purpose of making the chapter enjoyable to read. On a craft level, that kind of story is bound to be attractive to creators, but the real source of the appeal lies in the context in which the manga has been created. In theory, getting readers emotionally invested in the future of your manga is perfectly fine, but in practice it often ends up being more of a crutch than a safety net. An interesting premise, or an important goal that piques the reader's interest can also be used to hold readers' hostage as they wait for the story to get to all the interesting things that have been set up (if it ever does). In the meantime, readers slog through a story they would otherwise drop with an enthusiasm that is fueled exclusively by the version of the story that exist in their heads; basically using their own imagination as a substitute for the author's.

Akane-banashi's story structure throws away this option completely. If a reader does not enjoy a particular chapter, then they have no reason to continue reading the manga. That also means that they don't have to spend a single panel waiting for the good part to come, because Akane-banashi is only made of the good part.

During a Rakugo contest, due to Akane's straightforward approach to her story, she is the only contestant that is able to make her audience forget about trying to guess who will win the competition and simply lose themselves in her performance. Her lack of an ulterior motive is the source of her strength as a performer. Like the Kibataraki arc and the Rakugo contest arc that follows it, every conflict in Akane-banashi explores the differences between earnest and performative behavior, with the more earnest performer always coming out on top.

The manga's solution to the dilemma of surviving in Shonen Jump is consistent with this underlying theme. The story is written with the belief that the only thing a manga needs to gain an audience is for readers to enjoy a chapter enough to want to come back for more the next week. Any other attempt at securing attention would feel somewhat hollow, because neither the safety nets that can boost a manga's popularity nor an audience's lack of familiarity with the premise that would put its popularity at risk have anything to do with the actual reasons we love stories. A respect for the actual bread-and-butter of storytelling—the excitement of watching a well-structured plot come together, the catharsis that we feel when a particular theme resonates with us personally, the level of investment we can reach when characters are so developed that they barely feel fictional—is something that is shared equally by fans and creators alike, and any story that prioritizes popularity over quality is essentially saying that stories aren't important.

With all of that context, it's only natural that a manga about rakugo that is written as if the threat of cancellation doesn't exist would strike a unique chord with creators when it is serialized in the most competitive magazine in the industry. Akane-banashi is more than just an entertaining manga, it is an experiment as to how high this kind of story can go without compromising; an experiment that creators want to see succeed.

discuss this in the forum (6 posts) |