The Mike Toole Show

Imagawa Da Vida

by Michael Toole,

This month, Anitwitter is engaging in something called a “groupwatch.” “But wait,” you all say, every one of you, in a single roaring voice that echoes across the globe, “what's Anitwitter?” That's just a funny little portmanteau – “anime Twitter,” get it?-- used to describe anime fans on twitter. Do you use twitter to talk about anime a lot? Congratulations, you're part of Anitwitter! This “groupwatch,” organized by a Portuguese user called Soulstrider, isn't a thing where people gather in a chatroom and watch a stream together, like what Twitch allows users to do with video games. Instead, the idea is that, at a predetermined time, interested users all fire up the same show independently, and use a hashtag to comment on it together. It's an interesting phenomenon, and I've seen it done for everything from cult movies to weird cartoons. It works pretty well at creating a sense of community amongst people spread all over the world, and this particular groupwatch I'm telling you about features a 1990s OVA series called Giant Robo.

If you've been reading my work for a few years or more, you'll know that I constantly, obnoxiously tout Giant Robo as some sort of humongous classic. That's because it is. I'll get into what makes Giant Robo so memorable and special in short order, but I'm really just using it as an opportunity to discuss the broader works of its director, Yasuhiro Imagawa. By any chance, did you find yourself really into the Rocky Horror Picture Show when you were in high school? Congratulations, you've got something in common with Mr. Imagawa. As a student, Imagawa specifically latched onto one of the show's great lyrics—“Don't dream it, be it!”—and made it his motto. Filled with burning ambition, he enrolled in the Tatsunoko Anime Institute, because in 1979 Tatsunoko actually had a training school for animators (it's been closed for a long time).

Imagawa would later describe sitting next to a guy named Fumio Iida, who would eventually go on to become one of the great technical animators of the 80s, in addition to creating his own series, Yadamon. Watching the budding artist work, it dawned on Imagawa that he himself really didn't have any talent for animation itself. He was determined to stick it out, however, and a lucky meeting at Tezuka Productions saw him assigned to be the assistant to director Hiroshi Sasagawa on the TV movie Bremen 4. While not able to do the quick, detailed drawing required of animators, Imagawa proved good at improving scripts and tweaking storyboards, and just helping Mr. Sasagawa to make the film better. Tatsunoko saw the emerging value in his skills, threw him at Yatodetaman, and he was off to the races.

He'd spend much of the 80s refining his craft not as an artist, but as someone who could write and stage scenes extremely effectively, on a handful of popular Sunrise robot shows like Dougram and Heavy Metal L-Gaim. He was starting to get restless during production of Zeta Gundam, and when the opportunity to jump ship presented it, he took it, moving over to Shinei Animation and their new project, a TV adaptation of the popular manga Pro Golfer Saru. There, he continued to round out his skills, and after twelve episodes serving as both storyboard artist and director, it became apparent that he was ready to direct.

Consider that for a moment. Barely eight years after going pro, Yasuhiro Imagawa was directing a TV series at Sunrise. That TV series was an interesting one, too—titled Mr. Ajikko, it was an early example of manga about food and culinary stuff. Unlike Oishinbo, the standard-bearer for the genre, Mr. Ajikko wasn't a straightforward seinen series, but rather a family comedy about a kid who happened to be a genius chef. The demonstrative, grey-bearded Master Ajio, the “honorable master of taste,” travels Japan looking for new culinary sensations, and discovers Yoichi Ajiyoshi, the 13-year-old chef at the Hinode Restaurant. Yoichi is eager to learn from the acclaimed master, but when he follows him back to his company HQ, he draws the ire of the head of Ajio's Italian Food concern—who challenges him to a Spaghetti Battle!

Nobody at Fuji Television has ever outright said that their global hit TV series, Iron Chef, was inspired by Mr. Ajikko, but Imagawa will happily insist that his series simply had to have had some measure of influence. It's easy to see why he thinks that way—the show is rife with huge personalities, breathless narration, and pitched cooking battles and competitions between masters of the culinary arts. “Cooking battle” manga is now a staple, with Food Wars running in the popular Shonen Jump, but Daisuke Terasawa's original Mr. Ajikko was only a moderate hit. Using his penchant for theatrics and tension, Imagawa took a TV series that was initially planned for 25 episodes and kept it going for a whopping 99 installments. Sunrise, sensing they had a bold talent on their hands, next gave him the unenviable task of completely re-inventing Mobile Suit Gundam.

He didn't want to! He was right there with the rest of his generation in 1979, having his mind blown at the original Gundam TV show's conceit of robots as war machines in a brutal, complicated geopolitical conflict. But 1993's V-Gundam, despite being part and parcel of the master Universal Century storyline, had proven both unpopular on TV and sluggish in toy and model sales, so a new approach was desired by the sponsors. The director was agog at the central designs presented to him, including a weird football/boxing Gundam and a samurai Gundam, complete with metal topknot. Desperate to knock some sense into Bandai, he had his staff submit some deliberately bizarre designs, like the cape-wearing Master Gundam, to try and trip them up, but they faithfully turned around model kit designs that looked amazing. Forcibly pushed outside the box, Imagawa had to adapt quickly immediately.

With Mobile Fighter G-Gundam, Imagawa showed his genius by realizing that he would be creating a show for an audience of kids and young teenagers who did not necessarily grow up on original Gundam at all. With that in mind, he mined his own cinematic knowledge to create something bigger, broader, and crazier. He structured the series like one of King Hu's wuxia epics, complete with impassioned speeches and monumental kung fu battles between the amusingly stereotypical robots. When called to set some of the action in Paris, he used images lifted from Swing Out Sister's “Waiting Game” music video. Protagonist Domon Kasshu's apartment in the spacebound Neo Japan is directly modeled after the apartment in Woody Allen's Sleeper. When he dreamed up the idea of a German ninja, it made perfect sense—it was a great opportunity to model the character after the cheesy ninja from 1980s movies like Revenge of the Ninja. An ardent Trekkie, he named Noble Gundam pilot Allenby Beardsley after Star Trek: The Next Generation’s Ensign Tess Allenby. The series is fast, fun, and full of references like these. “I just wanted to make it cool,” he later confessed. Who wouldn't have?

In pulling G-Gundam together, Imagawa pulled off the frightening task of creating an all-new, all-different Gundam that audiences accepted. And despite the fightin’, silly-lookin’ robots, the special attacks with their own names and moves, and the larger-than-life characters, he managed to do so without being overly evocative of other popular fighting media, like Dragon Ball Z and Street Fighter II. And if he hadn't been occasionally cautioned by Sunrise execs to carefully control his “Imagawa color,” he could've done even better. He envisioned Stalker, the jolly Rod Serling/Mean Gene Okerlund hybrid who introduced each episode, slowly creeping into the narrative of the story and becoming an active character, for example. Here was a director full of great ideas, who knew how to stage them effectively.

And then, there was Giant Robo. Well, actually, Giant Robo came first, in 1992. Incredibly, Imagawa kicked out two episodes of this OVA series while he was also in charge of G-Gundam. Here, he was faced with a different daunting task—to create a splendid new Giant Robo anime, but not one featuring characters or situations from the old TV series, which still belonged to Toei. Imagawa had climbed aboard the project because of his fondness for Gigantor, and thought he'd be able to use that formula as a jumping-off point. But it was too similar. Instead, he ventured out to original creator Mitsuteru Yokoyama with a bold proposal. Absolutely certain that Yokoyama would turn him down, Imagawa pitched the idea of a Giant Robo starring not just the robot, but the heroes of all of Yokoyama's famous manga works, from Romance of the Three Kingdoms to Babel II to Sally the Witch to Mars to Masked Ninja Akakage. Incredibly, Mr. Yokoyama said yes, and history was made.

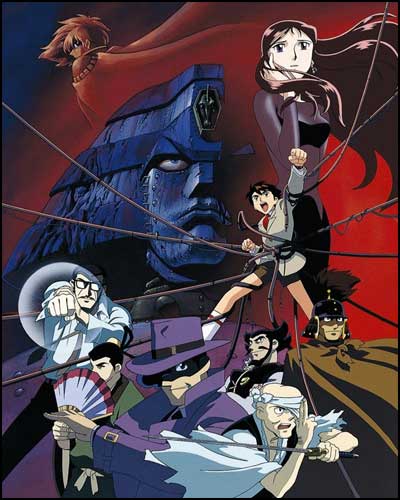

In G-Gundam and Mr. Ajikko, Imagawa's adeptness made itself known in a multitude of small ways, but here is his magnum opus, a bombastic, melodramatic, cracking good science fiction adventure that plays like every single great anime fight scene happening at once. Central to the narrative is the child, Daisauku Kusama, an orphan who's the sole controller of Giant Robo, a massive, fearsomely-powerful robot. Lined up alongside him are the Experts of Justice, which include a trio of rugged peasants from the swamps of Liang Shan Po, a comely secret agent, a rogue in a pink trenchcoat, a gifted scientist dressed in period Chinese finery, and a steely-eyed, pointy-bearded, pipe-puffing commander. Every single one of these characters has astonishing superpowers, most of them not evident until the story calls on them. The Magnificent Ten, high command of the Big Fire Organization, are the ostensible bad guys, with similar powers and backgrounds.

Imagawa presents us with a tantalizing flashback: years ago, a mad scientist defied his colleagues and unleashed a terrible calamity. The survivors are haunted by the catastrophe. But as good and evil draw their battle lines, this narrative slowly, lazily starts to pivot, and we learn that there are secrets behind the secrets. The Experts of Justice are filled out by the legendary “outlaws of the marsh” from The Water Margin, while Zhuge Liang, one of the great heroes of Romance of the Three Kingdoms, plays the role of scheming string-puller behind Big Fire. Beyond him is the true leader, Babel II—hero of one of Yokoyama's original classics. The terror of the original calamity is presented under the haunting tones of “A Furtive Tear” from the opera The Elixir of Love. There are scenes that evoke Godzilla and Frankenstein and La Dolce Vita. As two adversaries, lost sons standing eye to eye in their fathers’ dreadful machines, prepare to do battle, Imagawa gives the viewer a question: can happiness be achieved without sacrifice?

Along with the great story and atmospheric music and performances, what Giant Robo really nails is the look and feel of retro anime, but with modern production values. Imagawa really wanted to evoke classic-looking characters existing in ultra-modern settings, something that had been attempted without much success in earlier reduxes of fare like Gigantor and Sally the Witch. He hounded his character designers, Toshiyuki Kubooka and Akihiko Yamashita, relentlessly, until they got it right. It turns out that Imagawa can be a bit of a micromanager. Years ago, I met Kazuyoshi Katayama, the director of The Big O, who'd also worked on several episodes of Giant Robo. “What was working under Imagawa like?” I'd asked. “Was he really involved, or did he let you just get to work?” Katayama's bemused response was, “With Giant Robo, it wasn't ‘Okay, here's the storyboard, go and animate,” it was “alright, here's the boards, we're going to have a story meeting and I'm going to explain exactly what I want, and you have to follow my directions precisely, and I'm going to be hanging around and watching you carefully to remind you that it absolutely, positively has to be done this way.” He spoke highly of Imagawa and his razor-sharp vision, but when he and much of the Giant Robo staff kicked out the looser Super Atragon, he thought of it as something of a break, a reward for sticking with Imagawa and his challenges.

Ultimately, there was a series of scheduling problems that led to the final episode of Giant Robo being delayed for a whopping three years. Despite that, the team nailed the ending, cementing one of the finest OVA series ever produced. The series still has a legacy, a great and lasting intrigue. Imagawa had notes for two additional story arcs, Operation Domino (covering Daisaku's recruitment to the Experts, and a huge battle that would involve the defection of a major character to the Magnificent Ten) and Siege of Babel (an all-out war between the two sides), that were never animated. The Day the Earth Stood Still, the OVA's story arc, was the middle part! When asked why there wasn't more Giant Robo, Imagawa readily points out a sad and surprising fact: if the series had sold as well in Japan as it did in the US, he could have made more. At a 2002 appearance, Imagawa predicted someone else would revive Giant Robo, and he was right-- but what we got instead was a sloppily-animated revamp of the original live-action TV series. Seventeen years later, I think we can let the director's classic stand on its own.

For a lot of viewers in the west, Imagawa's legacy kinda starts with G-Gundam and ends with Giant Robo. But that isn't the whole story. Imagawa filled the gap between Giant Robo's last two episodes by writing the screenplay for Violinist of Hameln, a 25-episode fantasy adventure about a big war between humans and demons, with heroes that fight using magical music. This series was actually directed by Junichi Nishimura, but fans are quick to give Imagawa a lot of credit in helping make a rock-bottom-budget TV show pretty entertaining. Hameln doesn't actually look bad, beyond its pointy, outdated 90s aesthetic—it doesn't sport a lot of the sloppiness of modern crappy TV-budget anime, but instead it's positively crawling with long shots, shadows, offscreen dialogue, and other assorted “oops, we forgot to actually animate this” tricks. It's got a bracingly serious tone despite the puffy fantasy costumes and silly musical instrument names (here's Princess Flute! And Prince Trombone! And Oboe the bird!), and that great escalating dramatic tension that's so familiar to productions involving Imagawa.

I kinda wish there was a way for shows like Violinist of Hameln to get rescued, but short of the original licensor dusting it off and trying to get it to a streaming service (maybe? There was at least a 2008 DVD box in Japan), we won't be seeing it. I've mentioned Imagawa's next big project, Getter Robo: Armageddon, before. I do notice that now the Japanese Wikipedia article for it humorously states that there's no proof that Imagawa worked on it, since he isn't credited on the release itself. But come on—his participation was reported in Newtype, and he readily acknowledges his involvement in panel appearances and interviews. Apparently, when he was steering that ship, the plan was to somehow hitch it to the continuity of Giant Robo, which is briefly visible in one early shot. Wonder how that would've turned out?!

Yasuhiro Imagawa has always been very forthright about his inability to write female characters very well. He didn't really know how to handle Rain and Allenby in G-Gundam, and he struggled to make Ginrei a good character in Giant Robo. Recognizing this weakness, he addressed the problem head on with 2002's Seven of Seven, starring a junior high student named NANA and her seven clones, each of whom sports an extreme of one of her emotions. It's up to NANA and NANA and NANA and NANA and NANA and NANA and NANA and NANA to get that cute boy to notice her, all while trying desperately to prepare for high school entrance exams! This series is an odd duck—it was Imagawa's attempt to launch his very own property (he made it himself, unlike his other big works) , but sadly it wasn't that popular. Imagawa did a lot of things right with it—he had a great animation staff, who ensured that each episode had at least one or two crazy action scenes. He had the involvement of Mine Yoshizaki, creator of the popular Sgt. Frog, so his characters looked good. And he had one really interesting angle—the seiyuu star of his show was Nana Mizuki, in one of her earliest lead roles. She'd go on to amazing success, but even she couldn't lift the series up. It's a competent series, but there isn't really enough there to make it stand out. One fun fact: Imagawa's animation team kept trying to sneak in panty shots and other racy stuff, and he wanted to make a relatively wholesome show about a young girl, so he kept having to tell them to knock it off.

What else, what else? 2004 and Tetsujin 28, which I talked about this pretty extensively in the Yokoyama column. After that, he'd once again abandon the director's chair to write for Bartender, a 2006 seinen manga adaptation about the world's greatest mixer of cocktails. I briefly touted this in an old column as being one of several “lost” shows that came out in that period after the DVD boom but before streaming took hold, so it's sank out of sight. That's really too bad, because the show looks perfectly fine. Here, Imagawa's writing really shines—the show is documentary style, with the principal characters talking about their experiences in past tense, and how their bartender, Ryu Sasakura, the “Glass of the Gods,” gave them an amazing drink and just the right perspective they needed to get past their problems.

It sounds pretty cheesy, and it is. It's kind of ugly and workmanlike, something that fits right in next to all of the rest of the stuffy businessman manga (Example: The Fund Manager) in Super Jump. But Bartender also has some weird, intangible appeal to it, and I think we can hang that on Imagawa and his flair for drama and staging. There is something deeply, compulsively watchable about Bartender in spite of its plainness. It's gentle and sentimental, with powerful and surprising transitions. One favorite: after a revealing chat with the bartender, a pensive old ad exec has a heated conversation with his younger self. As he wanders darkened streets and slowly comes to terms with a past mistake, ads and billboards come alive as he passes. I think time's passed Bartender by, and it doesn't help that the show is loaded with product placement, including the likes of The Famous Grouse, Beefeater, and SUNTORY.

I've also talked about Mazinger Edition Z: The Impact! before, but I'll appreciate it just once more as another fine Imagawa directorial effort. This Mazinger Z redux is effective, because the director grew up with the original, and was always dssatisfied at the way the good guys always won because they were good, and the bad guys always lost because they were bad. Here, he presents Dr. Hell not as a mere ranting villain, but as a sharp, pragmatic scientist utterly consumed by his obsessions; the lewdly gimmicky Baron Ashura is also reinvented as a genuinely tragic figure. Fiery, heroic Koji Kabuto's absent dad returns early, and is scary as hell. Imagawa unearths, dusts off, and include as much Mazinger lore as he can possibly fit, plus the crazy robot attacks and dumb jokes aren't excised, they're just now part of something bigger and better. This series was just fantastic, so naturally it wasn't a success. Once again, Imagawa, flush with plans of Great Mazinger Edition Z, had to move on.

Today, he's still moving. He did some writing for a rubbish period show that ran in Comic Bunch, something that didn't even rate an ANN preview guide writeup. If you're a-hankering for more G-Gundam and Giant Robo from him, you're kinda in luck, as he's been writing for reboots of these properties in manga form in recent years. But he's such an important director; even more than most talented auteurs in the anime field, Yasuhiro Imagawa takes a very filmic approach to his work. When discussing what influenced Giant Robo, he puts aside super robot cartoons to talk about the importance of Woody Allen and Jean Luc Godard, of how he drew scenes and flourishes from Manhattan and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly to give his show a sense of time and place and weight.

I really want to see a new prestige project for the guy. Maybe a film noir-style mystery, with a female lead. Yasuhiro Imagawa has labored for decades to make his dreams real, and I'd like to see some more of them. How about you, reader? Are you acquainted with this storied director? If you won the lottery, would you give him eight or ten million dollars to make some more Giant Robo? Or has that ship sailed? In the meantime, that groupwatch I mentioned in the lede happens today (Sunday, February 8th) at 4:30pm EST. It'll go again next week. If you're on Twitter, follow along, or at least have a look at the #giantrobo2015 hashtag!

Here's a fun side question: that time I met Katayama, mentioned above? It was at Anime Central 2003. He was having a jolly verbal sparring contest with Hiroaki Gohda, who'd just done design and animation works for Please Teacher!. “American otaku clearly love my show more,” said Gohda, “look at all the Mizuho cosplayers here, and that fancy DVD box set!” “Fans here loved The Big O so much they got it renewed,” retorted Katayama, “and at least my show's been on TV in this country!” Twelve years later, which one has held up better? Talk about it in the comments!