Review

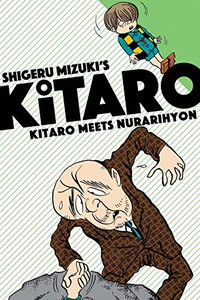

by Rebecca Silverman,Kitaro Meets Nurarihyon

GN

| Synopsis: |  |

||

In this second collection of Kitaro stories, Kitaro encounters not only Nurarihyon, the self-proclaimed leader of the Night Parade, but also the vampiric Odoro Odoro, a couple of evil old women, and several water yokai bent on destroying humans. Even when he wants to take a break, work is never done for the yokai boy, and not even his father or his sometimes-friend Nezumi Otoko can really help him! |

|||

| Review: | |||

Drawn & Quarterly's second collection of the late, great Shigeru Mizuki's Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro stories may be named after Nurarihyon, but he actually only features in one chapter. However, his essence definitely permeates the curated selection – Nurarihyon, who most western readers are likely to be familiar with from Nura: Rise of the Yokai Clan, is described by translator Zack Davisson as “com[ing] into your house and order[ing] you around…he eats all your best food and then struts out the door.” The self-proclaimed leader of a thousand yokai, Nurarihyon is ego incarnate, and that's a quality shared by most of the yokai Kitaro meets in this volume. Most of the stories contained in the book were published in 1967 and 1968, reflecting the quickly changing world of their time. Issues such as increasing dependence upon cars and rising costs of daily life are mentioned in passing, and one story, “Sara Kozo,” touches on the insatiable appetite for new pop music with a visual reference to Beatlemania. That story is the most culturally interesting in terms of the 1960s – it features a songwriter who steals a song from a Sara Kozo when he runs out of ideas. The Sara Kozo, a kappa-like water yokai with a mouth like a circular saw, is definitely not pleased to have his music taken and retaliates by hiding the band in a lost village, which appears to be a pocket dimension of some sort. While Kitaro does rescue the musicians and punish the Sara Kozo, he also makes it clear that he thinks both parties are at fault – the band for stealing the song and the yokai for overreacting to the theft. It's interesting commentary on intellectual property, but it's also a seamless blending of the real and supernatural worlds in a plotline that still feels relevant today. The Sara Kozo is not the only yokai to put his own desires first in this book. The eponymous Nurarihyon is angry with Kitaro for calling him out on his behavior, so he tries to kill him. In a Japanese version of Grimm's AT779 “The Hand from the Grave,” Kitaro's hand refuses to stay buried with his body, so Nurarihyon seeks help from the not necessarily evil (but definitely scary) Jakotsu Baba. This is a sign of the care and research Mizuki put into his stories – AT779 is largely centered in Europe, primarily Germany, Switzerland, and Poland, with few if any East Asian variants. Mizuki traveled the world studying ghostly folklore, so it's highly likely he encountered the tale in his journeys and decided to incorporate it into his Kitaro stories. It certainly adds some relatability for readers familiar with the story, who may also notice some distinct similarities between Jakotsu Baba, Datsui Baba, and the Russian folk character Baba Yaga. For potential younger readers, this can help to highlight cultural similarities, as well as open up an interest in folklore. As always, Mizuki's art is another major draw of the book. Almost more than in its first volume, Kitaro Meets Nurarihyon has a fantastic blend of realism, traditional Japanese painting, and cartoon art in every chapter. The breadth of Mizuki's talent is impressive – in one panel from the Umi Zato chapter, we can see cartoony Kitaro, a realistic ocean, and an almost Ukiyo-e depiction of Umi Zato himself. The coexistence of these three styles makes every page worth staring at, and many make you want to try and crawl right in to explore the landscapes. The major drawback is still that this is very clearly a manga written and drawn in the 1960s. Older titles tend to have more difficulty finding an audience, and this is definitely one that wears its date like a badge, albeit a badge of honor that isn't likely to deter anyone dissuaded by the way Mizuki drew his characters or the heavier style of the book. For some readers, the immersion into Japanese mythology may feel daunting. Davisson provides very readable notes on both the yokai and Mizuki himself, but that may not be enough to win over all contemporary readers. Despite that, I would encourage you to give this a try, even if you prefer your shounen dating to 2010 at the oldest – not only can you see where the genre got some of its ideas (and you can't tell me that some of today's shounen mangaka wouldn't love the idea of someone who pees huge amounts of poison on people), but the stories themselves are worth reading. There's a reason Kitaro is still a known pop-culture entity, and this book offers you a chance to find out for yourself. |

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall : A-

Story : A-

Art : A

+ Good cultural notes, stories are still a lot of fun, breathtaking artwork combining three distinct styles |

|||

| discuss this in the forum (7 posts) | | |||

| Production Info: | ||

|

Full encyclopedia details about |

||