Your Ghost in the Shell Cheat Sheet

by Brian Ruh,We are currently undergoing something of a Ghost in the Shell renaissance due to the impending Hollywood remake. Regardless of your feelings on the upcoming film, you can't deny that it's a good time to be a Ghost in the Shell fan. In 2017 alone, we're getting hardcover reissues of all of the Ghost in the Shell manga, a release of the original film in a special collectors' case, and license rescues of the second film and the television series on Blu Ray, to name just a few. There's so much out there right now it may be difficult to try to take it all in.

The roots of Ghost in the Shell date back to 1989 in the pages of Young Magazine. Masamune Shirow had recently finished the final volume of his landmark post-apocalyptic cyberpunk work Appleseed, and soon after kicked off the serialization of his new work that was similar in many respects. (Appleseed’s Duenan and Briareos even make a brief appearance in the background of the second chapter.) Shirow does a great job of setting the stage in the first few pages - a futuristic city, a bloody assassination, and a mysterious special cyborg agent named Motoko Kusanagi (which the author notes is "obviously an alias"). In eleven chapters, Shirow traces the founding of the secretive counterterror assault unit Section 9, its exploits and personnel, as well as the friction it encounters with the government and general populace. Kusanagi is the cyborg hacker who leads the unruly crew, and when she's not tracking down cyber-criminals, she's often sparring with her boss Aramaki and her compatriot Batou. Kusanagi is highly skilled at her job, but she also has something of an anarchic spirit.

Although the manga began its publication run over twenty-five years ago, it's really quite prescient when it comes to technology and how people relate to it. William Gibson's Neuromancer, the science fiction novel that popularized the term "cyberspace," had only come out a few years earlier, but Shirow took many of these concepts and ran headlong with them into a dystopian future that is both universal and specifically Japanese. (As Shirow puts it, the world is connected by “a vast corporate network covering the planet” and yet “the nation-state and ethnic groups still survive.”) But there is a glimmer of hope - at the end of the manga, Kusanagi merges her consciousness with that of a powerful net-born lifeform call the Puppet Master, and, freed from the constraints of her previous cyborg body and her employment with Section 9, she leaves to explore the expansive, interconnected world.

However, Shirow didn't stop writing Ghost in the Shell manga even after the seeming disappearance of his main protagonist. A number of these subsequent chapters are collected in English as Ghost in the Shell 1.5: Human-Error Processor. (This odd numbering is due to the fact that these chapters weren't collected into a tankoubon until after the sequel manga came out.) Kusanagi even makes an appearance as her alter-ego Chroma, but the main focus is on the rest of Section 9, including new recruits Azuma and Proto. Kusanagi returns properly in Shirow's Ghost in the Shell 2: Manmachine Interface, which began its run right on the heels of the original. In a departure from the previous stories, this manga took a new direction by focusing almost entirely on Kusanagi and her new life. Taking place "approximately four years and five months" after Kusanagi merges with the Puppet Master, which has given her new net powers. She has substantially upgraded her body, which is no longer the male version Batou left her with. (Surely Shirow couldn't be satisfied without the opportunity to draw more sexy women, although I'm sure there could be a perfectly plausible narrative explanation for this change in the interim.) She operates on her own, dealing in favors and information. We see her take on a new job to try to quell an uprising in a foreign country before it falls into chaos or anyone outside the country has to intervene. This is not her only mission, though, as her connected nature allows her to monitor and deal with issues in various countries and corporations simultaneously through multitasking and the use of multiple cybernetic bodies. It's a dense, layered tale that takes advantage of Shirow's increasing use of digital technologies to create his manga, rendering color and detail that really serve to enhance the world. I'd be remiss if I didn't point out that Shirow frequently places his heroines in some of the most ridiculous positions in order to get a panty shot, reminding us that in addition to being a SF manga artist, he frequently does erotic illustrations (and of recently he's done more of the latter, and unfortunately much less of the former.)

Coming off his work on the political mecha-thriller Patlabor 2, Mamoru Oshii was an obvious choice when Bandai wanted to create a theatrical animated version of Shirow's manga. After getting permission from the original author to make the film his own (perhaps due to some bad experiences he'd had earlier in his career), Oshii and screenwriter Kazunori Itō set about adapting the manga into animation. Since the original is sprawling with multiple narrative threads, Oshii and Itoh took bits and pieces from Shirow's work, changing them around as necessary. Kusanagi's encounter with the Puppet Master survived intact, although Kusanagi herself came off much differently in the film version. Gone was the cute, hard-partying leader of Section 9; in her place was a cool, somewhat aloof commander prone to thoughts about the nature of her cybernetic existence. (Although, to be fair, this was present to a degree in Shirow's original as well, but Oshii amplifies these aspects.)

Ghost in the Shell certainly made a splash when it came out in North America - one of its oft-repeated claims to fame is that when the video tape came out, it shot straight to the top of the Billboard video sales chart. This success wasn't entirely just serendipity - Ghost in the Shell was an international co-production with Manga Entertainment, who obviously saw a business opportunity for a certain kind of anime outside Japan's borders. At the same time, though, foreign money has been financing animation in Japan since Tetsuwan Atom (Astro Boy) in the 1960s. But perhaps there was something about Oshii's take on the franchise that rubbed domestic Japanese fans the wrong way. As Carl Gustav Horn points out in his afterword to the English-language version of the manga Seraphim: 266613336 Wings (a collaboration between Mamoru Oshii and Satoshi Kon from the mid-1990s), Ghost in the Shell was the first film Oshii directed that didn't make the cover of the venerable Animage magazine. By now, the fact that Oshii would take a property and give it his own artistic spin would have been known by Japanese anime fans - he'd been doing it since his early work on Urusei Yatsura, when he reportedly received razor blades in the mail from fans upset with the liberties he was taking with the source material.

A bit more of Oshii's arthouse flare can be seen in his 2004 sequel, Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence. In Japan, though, the film was just called Innocence, ditching the titular association with the first film, although it's plot would be rather incomprehensible to viewers who hadn't seen it. Similar to Manmachine Interface, this sequel follows on the heels of Kusanagi's disappearance after her merger with the Puppet Master. However, unlike Shirow's manga, the film focuses most of its attention on Batou and his longing to reconnect with his former unit leader. Although it takes one of the chapters from the original Ghost in the Shell manga as a loose framework, Innocence moves the narrative in unexpected directions. It is a dense work, filled with quotes and allusions to artists like Hans Bellmer and feminist cyborg theorist Donna Haraway. Although the first film balanced its philosophical qualities with a fair amount of detail-obsessed gunplay, Innocence only doles out the action in small, measured bursts.

Before Innocence hit the screens, though, another take on the world of Ghost in the Shell had begun airing on television in 2002. Kenji Kamiyama was something of a pupil of Mamoru Oshii, working in various capacities on Jin-Roh and Blood: The Last Vampire. Kamiyama's directorial debut was a set of comedic animated shorts set in the Patlabor universe called Minipato, for which Oshii had written the script. With this auspicious beginning, Kamiyama dove into the franchise that would begin to define him as a creator - Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex.

Unlike Oshii's take, Kamiyama stayed much closer to the tone of Shirow's original manga, though it's far from a slavish copy. The show is back to an ensemble piece, focusing on the members of Section 9, with most of them getting a share of the spotlight in the series at one point on another. The series starts with a handful of "adventure of the week" type episodes, showcasing the types of cybercrime that Section 9 has to combat in the Japan of the future. Although it's his first television series, Kamiyama gets off to a solid start and doesn't try to over-explain the world; each episode leaves things hanging a bit, which gestures toward a larger worldview and lets the viewers fill in the gaps. Whereas Oshii may have been influenced by Tarkovsky, Godard, and Polish cinema, Kamiyama seems more influenced by more mainstream films, which gives Stand Alone Complex a lighter feel that's a bit more akin to Shirow's manga. (There's also a sexualization of Kusanagi that's in keeping with the spirit of the manga. The most prevalent example of this is the ridiculous outfit she usually wears; it consists of a leather jacket on top of what looks like a high-cut swimsuit that's definitely out of place compared to what the other members of Section 9 wear.)

Kamiyama directed not only Stand Alone Complex, but the next series of 26 episodes as well, called Ghost in the Shell: 2nd Gig. Where the first series had a mix of episodes that told a contained story and those that involved an overarching plot dealing with a hacker known as the Laughing Man, the episodes of 2nd Gig had a much more cohesive arc to them. Even the ones that seemed self-contained often had connections to the general plot of the series. Mamoru Oshii was back on board the franchise as well, as he is credited with the "story concept" for the series. 2nd Gig demonstrates some of Oshii's pet themes of coup d'etat and revolution within Japan, but through someone else's directorial lens. Like the first series, 2nd Gig also draws many elements from Shirow's original manga - not just in the characters (the neglected Section 9 newbies Azuma and Proto finally show up here) and setting, but in some of the smaller details as well. For example, some secondary characters from the manga appear in different contexts in the series, and the interior of the Japanese courtroom of the future in 2nd Gig functions much like the way Shirow depicted it in the manga. This is something that comes up again and again in the various Ghost in the Shell anime adaptations - taking bits and pieces of Shirow's original manga (characters, scenes, shots, story elements, etc.) and repurposing them as needed.

After Kamiyama directed a feature turn with Ghost in the Shell: Solid State Society in 2006, it was a number of years before any more Ghost in the Shell animation was produced, in spite to the clamoring of fans. However, in 2013 a series of OVAs began coming out called Ghost in the Shell: Arise. Unlike the previous Ghost in the Shell stories, Arise depicted how Section 9 formed and begins before any of the characters really know their future compatriots. Just as Oshii's films were separate from Kamiyama's series, Arise also exists in a separate narrative universe that can't quite be reconciled with other aspects of the franchise. The series was written by science fiction author Tow Ubukata (Mardock Scramble) and directed by Kazuchika Kise. An animator with many years of experience, Kise had been an animator on both Innocence and Solid State Society and was one of the key people in the development of the Production I.G studio. The staff of Arise certainly knows their way around SF and Ghost in the Shell, but in my opinion something about it just doesn't click. I think a lot of it has to do with the character of the young Kusanagi, who is different from the Kusanagi that many viewers are used to in the films and TV series. It's not bad, but it doesn't quite feel like Ghost in the Shell.

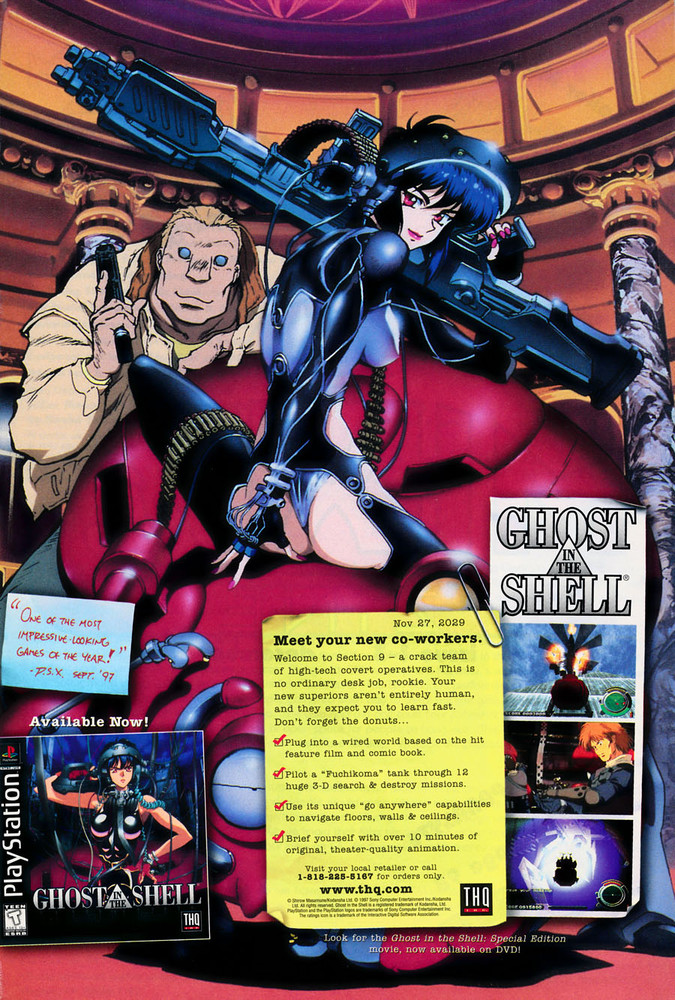

Although Ghost in the Shell has a long history in anime and manga, the franchise reaches out into plenty of other media as well, including video games going back to 1997. The original Ghost in the Shell PlayStation game is notable for its use of voiced anime cutscenes directed by Hiroyuki Kitakubo (whose previous work includes Black Magic M-66, another adaptation of a Shirow manga). This was definitely supposed to be a big draw because in Japan they even released a laserdisc that went into the production of the anime scenes for the game, and it's probably the animation that best captures Shirow's aesthetics. Surprisingly, for all the effort that went into the cutscenes, it was even pretty fun to play, as was the later Stand Alone Complex game for the PS2. There was also a PSP game and, more recently, an online first-person shooter called First Assault.

If pages rather than screens are your thing, there are a fair number of Ghost in the Shell prose books as well. Burning City, from 1995, is the earliest I've found; it was written by anime screenwriter Akinori Endo (3x3 Eyes, Armitage III), but it never made it into English. (It also had a gimmick where there are stills from Oshii's film printed in the corner, so when you grow bored of words you can use it as a flipbook.) However, there is a set of three Stand Alone Complex books that came out in English in 2006 which are worth tracking down. Although they're currently out of print, you should be able to find them for a few dollars apiece. Written by Junichi Fujisaku, who was a screenwriter on the television show, they're a fun diversion back in the Ghost in the Shell world. A bit more substantial, in both theme and title, is Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence - After the Long Goodbye by Masaki Yamada. Unlike the authors of some other anime-related novels, Yamada is an honest-to-goodness science fiction author (with wins of the Nihon SF Taisho Award and Seiun Award to his name), and the book ably shows off his chops. It's a hardboiled story that takes place immediately before Oshii's second Ghost in the Shell film, and actually helps to contextualize Batou's frame of mind. There's even a collection of Ghost in the Shell short stories coming out in English with contributions from the likes of Tow Ubukata and Toh Enjoe (the SF novel Self-Reference ENGINE, as well as a couple episodes of Space Dandy).

There's so much Ghost in the Shell out there that it may be hard to know where to begin, even after this brief primer. Sometimes it's best to go back to the roots, so I'd suggest starting out with Shirow's original manga and Oshii's first Ghost in the Shell film. They'll give you a good grounding in the overall world, and you can gauge your reactions to determine how to proceed. If you like things a bit more poppy, a bit more adventurous, then perhaps Stand Alone Complex should be your next step. However, if you find yourself enthralled with the philosophical questions of what it means to be "alive" in the digital age, then I'd recommend making your way to Oshii's Innocence. Either way, there's certainly a lot to explore out there. As Kusanagi herself says at the end of the first film, "The net is vast and infinite."

discuss this in the forum (25 posts) |