Grimgar of Fantasy and Ash and the Consequences of Death

by Rebecca Silverman,

Spoiler Warning: this article contains important story information from Grimgar of Fantasy and Ash, From the New World, Fushigi Yugi, Natusyuki Rendezvous, and Akame ga KILL!

Many words have been used to capture the melancholy of death and the hardship of mourning. In the Victorian era, Queen Victoria's grief at losing her beloved Prince Albert spawned an entire culture of mourning and death that outlasted her reign, and poets and other authors have struggled both to express the emotions wrought by losing someone and the space left behind by the deceased. While classic Japanese literature certainly has some fine examples dating back to the Heian era at the least (see Izumi Shikibu's poems mourning Prince Atsumichi), anime itself has largely shied away from treating the subject with the seriousness that it receives in other mediums. Characters are killed off-screen, brought back to life, and reincarnated; deadly injuries are treated as flesh wounds, and even when the death is final, there is little to no period of mourning for the deceased, just a quick tear or two artistically falling down a porcelain cheek before the story moves on. It isn't surprising, perhaps, given that anime in its origins catered to a family audience, and indeed many shows still do, regardless of the fact that plenty of family shows have adult fanbases. This is what makes Grimgar of Fantasy and Ash, based on the light novels of the same name, unusual - not only has it killed a main character five episodes into the story, but it also then took the next three episodes to properly mourn him. For the characters in Grimgar, Manato's death is not easily forgotten, and the result is that the fantasy story becomes more grounded and in some ways more realistic than many slice of life shows. This begs the question of why Grimgar is unique in this aspect. Why don't more anime titles take death more seriously? The answer is probably somewhere in a vast catalog of coping mechanisms and a wish to protect viewers from that particular type of sensitive material, which leads me to look back and think about how other shows have typically handled the death of a character – and why those methods ultimately don't have as much power as Grimgar's emotionally honest portrayal.

The Ghost Effect

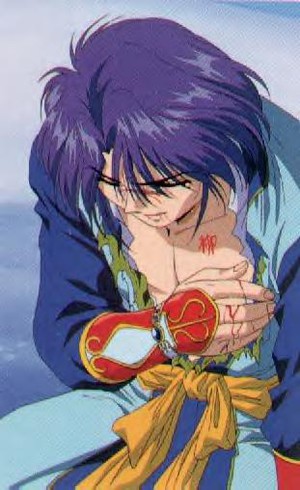

Very few people really know what comes after death, and one of the more popular theories is that the spirits of the departed can still be found as ghosts. Whether or not you believe in them, ghosts and ghost stories make up a large part of the literature of death in almost any culture, and anime is no exception. We see the “ghost effect” across genres and demographics, often with the goal of getting some emotional leverage out of a character but not wanting to derail the actual story. One title that comes to mind is Fushigi Yugi, which kills off a number of the chosen warriors of the Priestess of Suzaku before the final summoning can be enacted, presumably calling into question Miaka's ability to actually pull it off and win the day. This is never really an issue, however, because all of them are still able to help her, creating in the viewers' minds the thought that “dead” does not mean “gone,” and therefore a character who has passed away is still easily brought back under the right circumstances. This takes the emotional charge out of the death scene, reassuring us that no matter what, they can return if we really need them to. While this is certainly comforting, it also shows that death scene as the cheap emotion grab that it is, never a real threat to a favorite character or the heroine's cause. It makes us think that no matter what character died, there is still a chance of them returning if you want it or need it enough. That's not a bad thing in terms of the viewer's emotional health, perhaps, but if we're looking at it in terms of storytelling technique, it's a cheat, robbing the story of its lasting heft in favor of a quick fix for a pothole in the plot. This is never a possibility for the characters in Grimgar of Fantasy and Ash – they watched the life fade from Manato's eyes and were present at his cremation. They held the ashes of his body in their hands; they know there's no way he's coming back. Instead of being secure in the knowledge that death is somehow temporary, both they and the viewers are faced with the very real fact that they are now minus a healer, and that no matter what they do or who they find, it will never be Manato again and their future is incontrovertibly changed. There is no easy way out.

Ghostly Visitors

Another way this particular technique of “returning” is used can be seen in Natsuyuki Rendezvous, where the deceased is always present as a ghost but the object of the ghost's affections cannot see him. Also seen to a degree in anohana, where the deceased returns as a ghost to “fix” the living and move on to the next world, this way of dealing with death is less of a cop-out on the part of the writer(s) but still lacks the basic honesty of Grimgar's handling of the issue. In part the problem with this technique when used as Natsuyuki Rendezvous does is that it invalidates the existence of one of the living characters, in this case ostensible male protagonist Hazuki, jettisoning him for six of the series' eleven episodes so that his body can be used by the ghost in question. While this does superficially offer both Rokka and Atsushi the chance to come to terms with Atsushi's death, it does so by creating a false sense of comfort in Rokka's mind, depriving her of the chance to really accept her grief. Grieving is a miserable process by anyone's estimation, but it is an important one. None of us get the chance to say that one more thing, and coming to terms with it is part of the process of being human. We can assume that Shihoru, who was being slowly courted by Manato in Grimgar, has many regrets similar to Rokka's, and eventually they may allow her to open up to her fellow party members as she begins to in episode seven. If Manato's spirit had possessed one of the other characters, that chance would be lost, not allowing Shihoru to grow as a character and leaving her in her shell, which, post tragedy, she is starting to come out of. A case like anohana's, on the other hand, does work a little better, giving the characters a chance to work through their grief on the assumption that the deceased wouldn't want them to continue mourning, and for some people, that is a thought that can help them to move forward. But putting the actual ghost into the story is taking the easy way out, giving the grief a physical form to be vanquished in reality. As a metaphor, it works, but in the suspended disbelief of anime as a medium, it makes for, if not a trivialization, at least an easy fix. When Haruhiro “talks” with Manato, we understand that he's doing that in his mind as a way to cope with the heavy charge Manato gave him with his last breath – to take care of everyone. He needs to feel that he can do that by taking some of Manato into himself, and with Manato's notebook, he can. But even then he knows that it is only an artifact, and that ultimately he has to make the choices himself, because there is no friendly ghost to tell him what to do. Grief can be the heaviest emptiness you'll ever carry, and stories that try to get around that by giving the deceased form skirt around that solitary weight.

Speedy Reincarnation

Similar to the ghostly presence in anime is the idea of reincarnation. Reincarnation is a staple belief of many religions, and as a religious belief, it is an important part of the grieving process and a natural follow up to the technique discussed previously. The problem arises when anime allows the deceased to be reincarnated too quickly, taking all of the emotion out of the death. Now I'm not talking about cases where a physical repair mechanism is used, either seriously, like in Black Bullet, or humorously, like in Bludgeoning Angel Dokuro-Chan – those are legitimate comedy or science fiction plot devices. The issue arises when a character dies at some point during the episode (and is clearly dead) only to return intact at the end of it. This is a common ploy specifically in magical girl shows, with Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon being the most obvious to use the device. Throughout all five seasons of Sailor Moon's anime version (and, for that matter, the original manga), the Sailor Guardians are repeatedly killed off and brought back with a minimum of fuss and bother. The first few deaths are genuinely horrific, but by the time everyone dies in the fifth season, it has lost its sense of reality. These girls die; it's a standard part of the Sailor Moon storyline. We don't have to worry about it because within episodes (or in some cases, minutes), they will be back, possibly lacking a little memory, but hale and hearty and ready to fight the next set of villains. Phantom Thief Jeanne pulls something similar with the character of Zen, whose death is important in the story but who is seen reincarnating as an angel later on – more touching, to be sure, but still proof that he isn't really gone. It's an issue we see tackled to a degree in Log Horizon, where Adventurers, the former player characters, cannot actually die, taking the threat and challenge out of the “game,” and in that story it is used to point out the unreality of their new lives inside Elder Tales. Grimgar of Fantasy and Ash could very easily have pulled that same trick, or at least one like Sword Art Online where their bodies aren't real so that the realities of what death leaves behind (a corpse) doesn't have to be dealt with by the characters. By eschewing easy reincarnation and magically pixilating bodies, Grimgar forces the realization that death in this world is forever. There's no scene of Manato ascending to another world, no baby being born at the exact same moment, just a sad pile of carefully folded belongings and a handful of ashes. His “replacement,” Mary, isn't a literal replacement at all, as she doesn't fit in with the group at first or even act in the same way Manato would have. Gone in this world means gone, and hard as it is, the characters have to accept that.

Instantly Replaced

Mary's entry onto the scene in Grimgar is, in some ways, what really drives home the reality of Manato's passing, largely because it is a direct refutation of the “instant replacement” phenomenon. This is when a character is killed off but almost immediately replaced by someone very similar, essentially the same person with a different body. One of the most recent, and egregious, examples of this is in Akame ga KILL!, where the deaths of Sheele and Bulat are mourned for maybe one episode before talk of actual “replacements” begins – and when they arrive, they are a large, bulky man and a slender, cute girl, just like Sheele and Bulat. Yes, their powers and personalities are different (although an argument could be made about Bulat's sexual orientation and the stereotypically “gay” actions of Susanoo, his replacement), but they really just fill the visual gaps left behind by the others' deaths. From the New World follows the same basic pattern by giving, in the manga at least, Saki a series of doomed lesbian lovers – any girl or woman who sleeps with Saki ends up dying to the point where it ceases to matter who they are the moment they have sex – if it's with Saki, they will die, and their individual personalities cease to matter as they become a joke unto themselves. This robs their deaths of significance, as well as setting Saki up as more or less “invincible,” a feeling which is carried through to the end of the story whereas Grimgar crushes that illusion with the realization that no one is safe and no one can simply be replaced. Certainly other shows before Grimgar have made efforts in this direction as well; the entire story of Prétear is based on stopping the former Prétear, Himeno's predecessor who previously shared many qualities with her and Shigofumi's use of letter from the dead has strong implications in this direction as well. Both of those, however, flavor their messages with fantasy elements that are more than just the settings, giving them a cushion to soften that message with. The story can be more easily dismissed based on the unrealistic elements of the rest of the series, whereas the only real “fantasy” element of Grimgar of Fantasy and Ash is the fact that they are in a nominally fantasy world. Other than that we still see the characters go through the motions and worries of daily life in an unembellished fashion, giving it more the feel of a medieval setting than a fantasy one. It's this everyday quality, the way the party has to learn to cook, clean, and hunt fairly realistically that makes the ideas presented stick so much harder; in fact, the goblins (one of the more “magical” aspects of the story apart from the actual magic) are increasingly portrayed as having a culture and society of their own, making the humans' efforts to kill them more questionable. At some point we may have to wonder if someone is mourning each dead goblin as well.

There have certainly been other shows before Grimgar of Fantasy and Ash that have tried to tackle the question of how we relate to death and mourning; Sunday Without God is about just that, and elements of series such as GATE (with Tuka's father) and Orange also touch on how we manage loss. But Grimgar's peculiar strength is in the way it presents it with no flourishes, just the stark reality of what it's like to lose someone close to you and how everyone goes through the mourning process a little differently. It doesn't skip over the ugly details or how long it can really take to get through a death – in fact, it suggests that we don't move on, we just learn how to get through. The deceased remain with us, scars on our hearts and voices in our heads we talk to from time to time, or haunting memories we can't quite shake. Whether you find it melodramatic and slow or a faithful portrait of mourning, Grimgar of Fantasy and Ash does its best to remain faithful to the harsh details of death's aftermath, and in that respect, it stands out.

discuss this in the forum (30 posts) |