Isao Takahata: Endless Memories

Prologue

by Carl Horn,

Prologue

I once wrote that Isao Takahata was anime's greatest director—when he felt like it. Maybe Hayao Miyazaki, who is anime's greatest director even though he doesn't feel like it, had the same opinion of him, and that's why he famously regarded Takahata as the “descendant of a giant sloth.” Because it must have been tremendously frustrating to an artist as supremely industrious as Miyazaki, an artist hungry for excellence, for something human, to regard Takahata, who could deliver these things as well or better as he, and made fewer films in the course of a longer career.

So Miya-chan made not a petty gripe, but a profound one. Made more so by knowing that his own final score is made in part of what Takahata gave to him, for, as Toshio Suzuki said to Helen McCarthy in the course of researching her groundbreaking Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation, Miyazaki felt that Takahata understood him and his work better than anyone else. And because even more than being sustained in one's life, having that life made greater still by knowing them—that's all we might hope for from a best friend.

Who are these friends I'm talking about, anyway, Isao Takahata, Hayao Miyazaki? It depends on when you ask. In the 1970s, Takahata was the guy making the shows that the first generation who should have grown out of anime watched—Lupin III, Heidi, 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother, Anne of Green Gables. To those same otaku, a little older in the 1980s, Miyazaki was the guy for whom they lay down on cardboard all night, waiting in line for the premiere of a movie that would always be their favorite of the year. Those things would change; there wasn't as yet so much distance between them and us. We would have been talking about them back then too, but we would have said different things.

You often hear that many anime fans have an intense period of three or four years where they keep up with the new shows as best they can, then gradually flutter away from the scene. If so, it makes for a beautiful Ghibli image—in the deep forest, a sparkle and fade, a dozen generations of butterflies about the oak tree. That was Takahata, who made anime for half a century.

If you haven't seen his (insert work from the past, and now of a dead man), you're not a true anime fan. I shout that now out of one side of my mouth, but the proclamation rings a little false to me. And hypocritical. When I became an otaku in 1982, when the spark first leapt, as it does, from the screen to your eyes, my thinking wasn't, “Now I must set out to familiarize myself with the history of anime, all its landmark works…” No way. Although it was a 1970s show that got me into anime (Space Pirate Captain Harlock), so many 1970s shows already seemed “strange” in style to me. Old-fashioned. I wanted to see what was coming out now. And I think that must be, ironically, a traditional experience, no matter when you realized that, unlike the other kids who were into anime, you were really, really into anime. Yes, 1980s anime was, how shall I put it, aesthetic. But in 2018 it has lost none of its potential to seize, to entrance, to set you on fire. You, I mean. An otaku is one who burns, cold and sulphurous sometimes.

Pausing a moment in the midst of today's trendy anime, to lecture the youth about Isao Takahata—it's not a new thing. In fact, the first instance of this happening was in 1978. The debut issue of Animage, the oldest anime magazine in Japan still running, had just hit the stands, and it had the hottest anime of the day on its cover, the then-in-the-theaters film Arrivederci Yamato. And inside, an eight-page feature article on a movie many readers were not old enough to remember, or had never even heard of—Isao Takahata's Horus, Prince of the Sun. Because it was already ten years in the past.

In that grand tradition, I have had, and still do have, so much to learn about Takahata. Many other writers will be contributing to this retrospective series and bringing their knowledge, so before they do, I would like to share just one anecdote of my ignorance.

In his own country, Isao Takahata had admirers beyond and above the animation community. One of the most important Academy Awards given out, from a global perspective is, understandably, that for Best Foreign Language Film. Every nation has its own procedure for choosing which movie they submit each year, in hopes of it being nominated. Japan decides this through a committee associated with the MPPAJ, the Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan (to be exact, its big four—Shochiku, Toho, Toei, and Kadokawa) which organizes an expert jury to select the pick. There is no guarantee, of course, that Japan's official submission will actually get chosen as a Best Foreign Film nominee, let alone win. But their submissions over the decades have reflected a pantheon of internationally known directors—works from Kurosawa, Ozu, Ichikawa, Oshima, Imamura, Fukasaku—as well as figures beloved in Japan but less known abroad to many cinema students, such as Yoji Yamada.

Lest you think it is only the American film establishment that might sell anime short, the jury assembled by the MPPAJ—despite the fact the studios that comprise it are all involved with anime, some heavily—has only twice in the past seven decades ever decided that the very best film made in their country that year was an animated one. They're too exclusive a committee, perhaps. They're unmoved by “Cool Japan,” certainly. No anime film in the 21st century has yet made their final cut—not even Spirited Away. But if you want to call their official judgment of anime's achievements within Japanese cinema strict, even snobbish, it's worth noting Miyazaki's Princess Mononoke was the second of those two anime films that so impressed them. The very first anime to earn their highest respect was by—well, you can guess who it was by.

As anyone familiar with the movie will attest, the decision took big balls, and an American jury probably wouldn't have picked Pom Poko as the first Isao Takahata film to send to Hollywood. But remember, this is a story about ignorance—my ignorance.

As I said, the MPAAJ's committee is pretty serious. They could have instead, for example, chosen to submit the movie that won the Japanese equivalent of the Best Picture Oscar that year (Crest of Betrayal by Kinji Fukasaku). Or the movie that won that year's poll in Japan's venerable film journal, Kinema Jumpo (Kazuo Hara's A Dedicated Life—and if you ever get tired of how anime, free-to-play games, or light novels choose to re-imagine WWII, watch Hara's 1987 The Emperor's Naked Army Marches On). But they didn't; that year they chose Pom Poko, and as the first anime film ever chosen to officially represent the best of Japanese cinema, they were in effect also saying it was, at that moment, the greatest anime film ever made.

But, come on. What did they know? I was an otaku, and I had my own opinions. Here's the thing; I personally didn't even watch Pom Poko when it first came out, and it wasn't because of the hacky-sack maneuvers. It was because of the tanuki who were the protagonists—them critters, just a-singin' and a-playin' and a-carryin' on. I was of a generation that associated funny, musical animals with American cartoons, which is what we were watching anime to get away from. Look: the most talked-about anime in the year before Pom Poko was Mamoru Oshii's Patlabor 2. I wasn't about to pivot from that to what looked like anime's answer to the Country Bear Jamboree. Never mind, apparently, the fact Takahata's previous film, Only Yesterday, had instantly become my most respected anime movie after Royal Space Force (Takahata, unlike Miyazaki, was not an admirer of RSF). Never mind even the fact it took me so long to get into Patlabor because I wasn't especially into “mecha shows.” No—as an otaku, I knew what I knew, so you know what, I was just going to give Pom Poko a miss. That year I wanted to hear Sharon Apple sing, not a pack of raccoon dogs.

So what I had been missing, of course, was Isao Takahata in that mood which came upon him now and then, when he felt like being anime's greatest director, by doing what was his lifelong specialty—making anime do what we had never thought to ask of it before. In this case, use anime to make a great Japanese film about a Japan that Japanese people recognized—what a concept.

Make no mistake; Takahata was, in time and money and process terms, the most indulgent director anime has ever produced. It had serious consequences—for him, for his collaborators, for his studios. I don't doubt that a number of people writing on Takahata will bring up the tremendous importance to the director's continuing career of his great admirer and sponsor in the business world, the late media and advertising executive Seiichiro Ujiie. As the onetime head of NTV, one of Japan's major TV networks, as well as president of Japan's National Association of Commercial Broadcasters, Ujiie was not only a powerful ally for such an individualistic artist as Takahata to have up in the boardroom, but also a well-connected international patron for him in the classic sense, serving as chair of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo and as an important supporter of the Musée du Louvre.

Yet it wasn't indulgence as we usually understand it from our favorite anime creators. In his official studio biography, Hideaki Anno tells of the despair he developed after working upon Takahata's Grave of the Fireflies; Anno had been given the job of animating the ship the children's father served on, the famous heavy cruiser Maya. The romance of the Imperial Japanese Navy would run deeply through his own directorial debut later that same year, Aim for the Top! Gunbuster, and of course, so many of the characters in his most famous work, Evangelion, are named for those lost ships—Ayanami, Soryu, Katsuragi, Makinami, Kirishima. As you might expect, Anno did a beautiful job animating the Maya for Takahata in meticulous historical detail; it took him a month's work to complete it. What he didn't realize is that Takahata's finishing touch to the sequence would be to shroud the motion of the ship in shadows, where ignorant armies clash by night. It was no longer a model kit, but real. And as Takahata had complained, in anime, one is not allowed to depict Japan in a realistic manner.

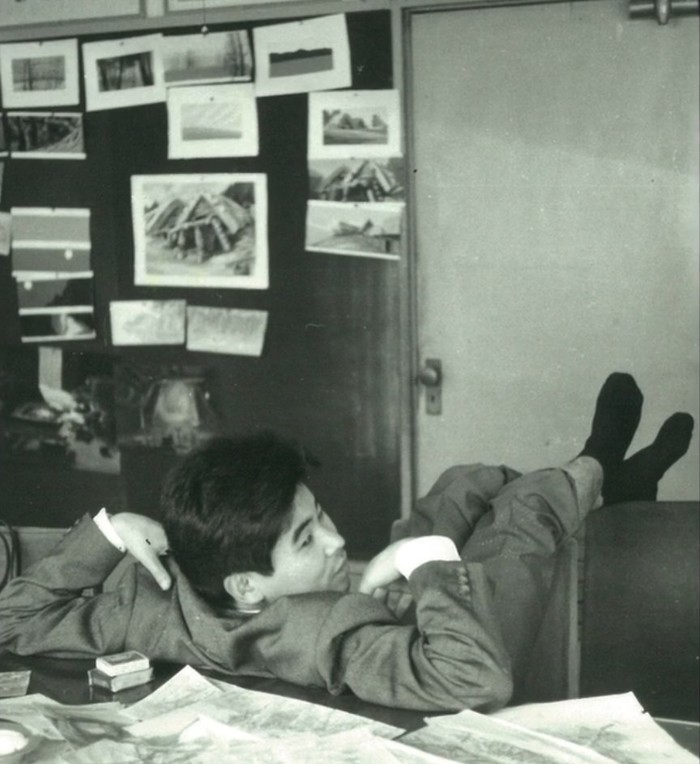

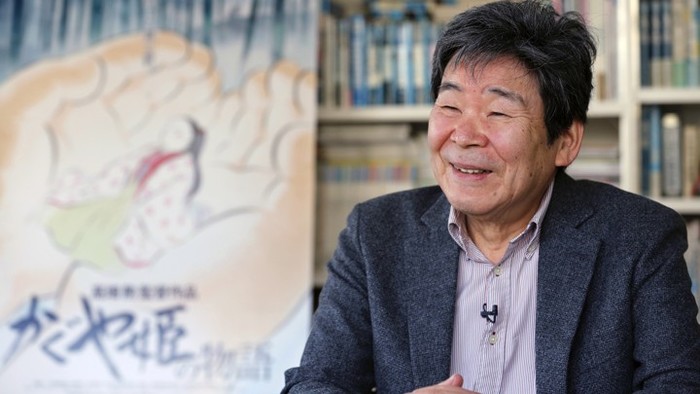

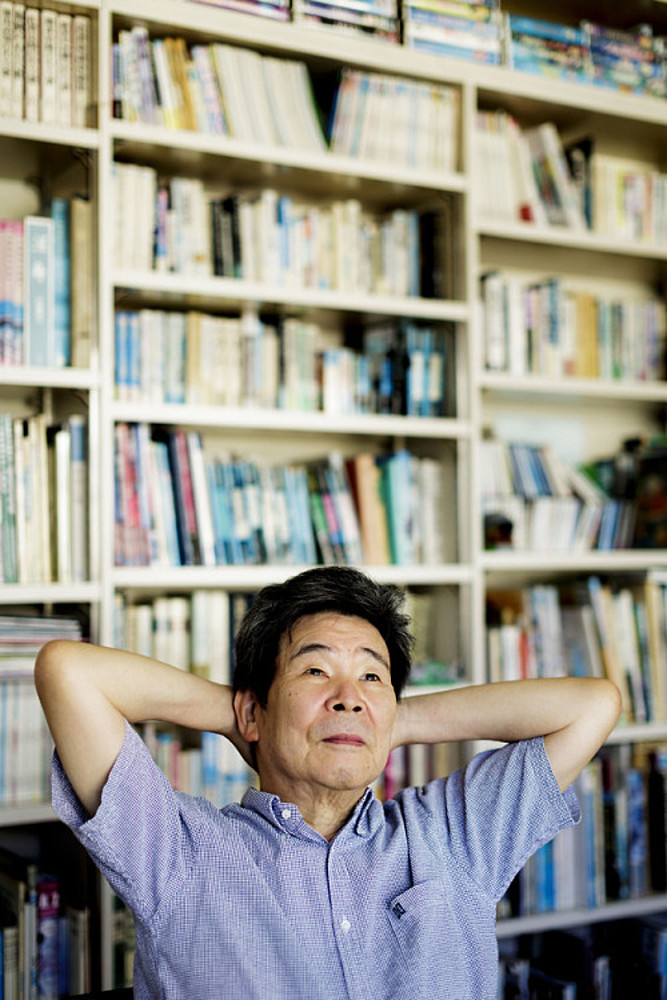

Takahata was five years older than Miyazaki, but never himself adopted the mien of an elder; no beard, no glasses, not even a white hair—as a 79 year-old at the Academy Awards for his final film, the thick thatch he had sported his whole career was now mingled with gray, but that was about it. It isn't so surprising that Miyazaki was quoted as saying he had expected him to live to be 95. I even remember hearing some talk after Princess Kaguya that he might be considering just one more movie, and the general sense was that if he wasn't likely to finish it, it wouldn't be because of his age so much as his slowness. I'm glad I cried at his work while he was still alive. He took his time, and as for anime, he was always ahead of it somehow.

Isao Takahata: Endless Memories is a week-long series that will continue tomorrow with a look at Takahata's earliest work. Join us!

discuss this in the forum (61 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history

back to Isao Takahata: Endless Memories

Feature homepage / archives