Anime vs. The NES

by Todd Ciolek,Some games made no secret of their anime or manga origins: ads for the first Golgo 13 title included a coupon for a free comic, while Puss 'N Boots had a box-copy blurb proclaiming the character as the mascot of Toei studios. Other anime-derived had their origins obscured, however, as companies either didn't mention the connection or deliberately changed the games—often with bizarre results.

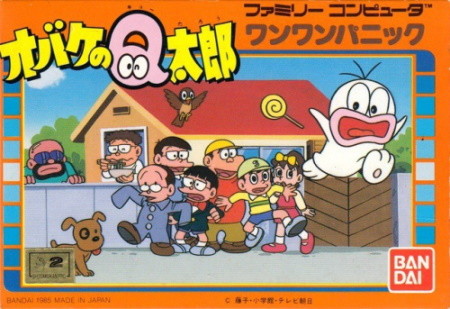

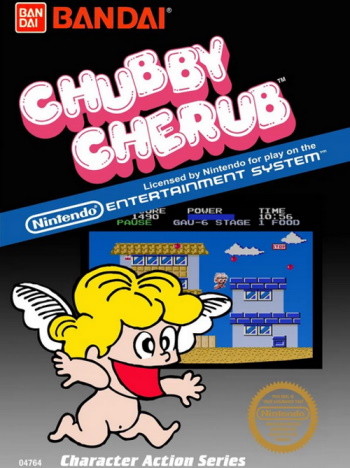

1. CHUBBY CHERUB

Bandai was among the first allies Nintendo had in their daring attempt to re-ignite America's game-console market. A year after the system's test-market debut, Bandai had a trio of releases to fill out the library.

Not that Bandai took risks. No, Bandai just seized three anime-based games from the Famicom, the Japanese equivalent of the NES, and re-worked them for the Western market. One of these was a Kinnikuman wrestling title easily re-branded with its American equivalent: M.U.S.C.L.E. The other two games lost their anime roots entirely.

In Bandai's defense, a statistically microscopic section of NES owners were aware of Obake no Q-taro, the comedic manga and anime series from the creators of Doraemon. It was a solid success in Japan, but Bandai had no qualms about taking Obake no Q-taro: Wan Wan Panic (or “Woof Woof Panic”) and replacing its dog-fearing ghost hero with something more marketable to American children of the 1980s. And what did those children like more than anything? Gluttonous angels.

The cynophobic spirit protagonist of Wan Wan Panic became a floating angel hero named Chubby Cherub, and the gameplay stayed largely the same, as its hero floats through the air, gobbles assorted treats, and dodges dogs and other animals. He also journeys to a cloudy heaven and a lightless hell, though not with any décor that would invite Nintendo's kid-safe censoring.

It's a drearily repetitive game in either form, and any hopes Bandai might have had for Chubby Cherub's international appeal vanished rapidly. Although the NES had a little over two dozen games at the time, no one latched on to Chubby Cherub.

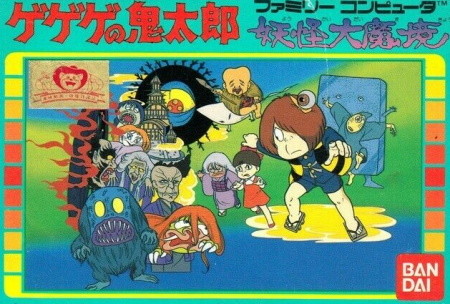

2. NINJA KID

Ninja Kid is a case study in shifting tastes. Today, Nintendo's Yokai Watch openly pitches American kids games, an anime series, and merchandise filled with creatures from Japanese folklore. In 1986, however, yokai were a tougher sell, and so was a classic manga series about them: Shigeru Mizuki's GeGeGe no Kitaro.

So when 1986 found Bandai with a GeGeGe no Kitaro game, it was overhauled in favor of a more marketable Japanese pop-culture export.

Ninja Kid turned the dour, long-haired Kitaro into a wide-grinning shinobi protagonist. His allies are similarly changed, and he now fires ninja daggers instead of Kitaro's detachable fingers. The gameplay is largely unaltered beneath the surface, as players wander an overworld of castles and surprise attacks, with side-scrolling levels where enemies can take out the hero in just one hit. At least it's a better game than Chubby Cherub.

Some of the enemies saw similar makeovers, as Bandai needed to add ninja foes for the titular Ninja Kid. However, many of the yokai remain the same—including some Frankenstein monsters in an otherwise medieval Japanese setting. Perhaps a few NES owners might have suspected that they were playing a hodgepodge of ninja clichés and gloomy supernatural horror, but most went through Ninja Kid unaware.

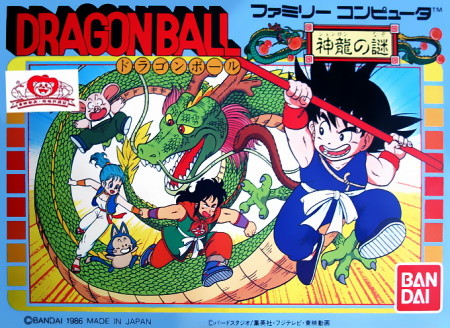

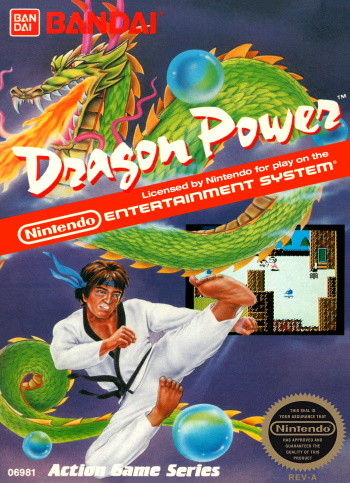

3. DRAGON POWER

There was a time when North America didn't understand Dragon Ball. In the late 1980s Harmony Gold attempted a dub of the anime series, changing a few names and excising some suggestive elements. Bandai made deeper alterations with Dragon Ball: Shenron no Nazo for the Famicom.

Sticking with the same method that brought us Ninja Kid and Chubby Cherub, Bandai gave Goku a haircut, cleaned up some risqué humor, and called the game Dragon Power.

Granted, the makeover wasn't as severe as Bandai's earlier efforts. Anyone who'd encountered imported Dragon Ball manga or anime would recognize characters like Bulma and Master Roshi—and surely see through Dragon Power's efforts to turn a notorious gag about underwear into a joke about triangular “sandwiches.” It's only Goku who looks radically differently. Rendered more monkeylike on both the conversation screens and in the gameplay, he more closely resembles his direct inspiration: Sun Wukong from Journey to the West. In effect, Bandai wasn't censoring Dragon Ball. They were just sanding off creator Akira Toriyama's new coat of paint.

Bandai's efforts came too late. Dragon Power's overhead action was more complex than the typical NES game of 1986, but it didn't arrive in American until 1988. By that point the NES dynasty was in full flower with titles like The Legend of Zelda, Metroid, Contra, and Mega Man. Dragon Power felt primitive, even for fans who saw through its disguise.

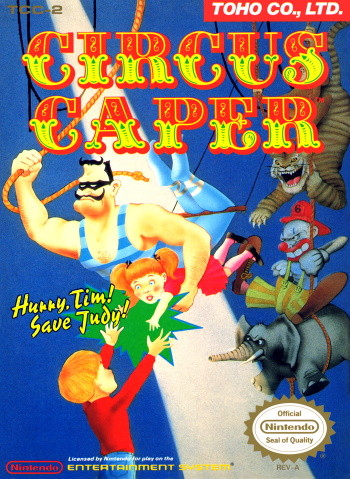

4. CIRCUS CAPER

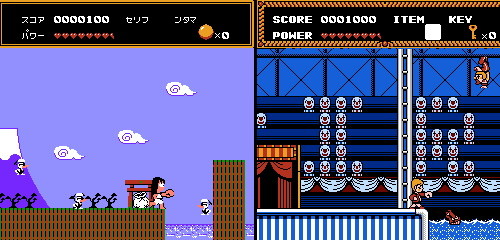

The success of the NES brought many publishers to the table in North America, and one of them was kaiju-film powerhouse Toho. Godzilla games headlined their NES catalog, of course, but the company evidently wanted something less monstrous for backup. A candidate appeared in a side-scrolling Famicom game based on Moeru Oniisan, a manga and anime about a karate master raised in the wilderness and forced to adjust to city life.

Bandai was content to change a few characters when overhauling anime-based games, but Toho scrubbed away all trace of Moeru Oniisan and turned it into Circus Caper. The original game's mountain landscapes and oddball creatures are gone, replaced by carnival backdrops and evil clowns. Only a few vestiges remain in the premise: instead of Moeru Oniisan's protagonist saving his sister from a mountain dragon, Circus Caper's boy hero rescues his sibling from a big top of terrors.

It's enough to make one ponder why Toho didn't just commission a new game from the ground up, though the underlying play mechanics are mostly the same. Circus Caper loses an RPG-like final boss, but it keeps the side-scrolling focus and mini-games where the player dices with clowns. There's even a “teriyaki battle” where the hero snatches food from a white tiger. Every circus has teriyaki battles, right?

Like many a mediocre NES game, Circus Caper spreads a kid-friendly theme atop a rigidly challenging experience. The results didn't appeal to many players, and let's face it: even if Toho's little experiment had turned out amazing, children of 1990 didn't really care about the circus.

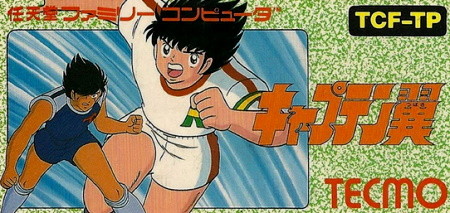

5. TECMO CUP SOCCER GAME

Captain Tsubasa is one of those manga and anime series that's popular just about everywhere except the United States. Fitting, since it's all about soccer. This didn't bother Tecmo, however.

Tecmo decided to bring a Captain Tsubasa game to North America—with many alternations and the title Tecmo Cup Soccer Game. It would fit perfectly on the shelf next to Tecmo Football Game, Tecmo Puzzle Game, and Tecmo Ninja Running and Slashing Action Game.

Hoping to appeal to an older audience, Tecmo replaced Tsubasa and all of his young teammates with adult players, including a new protagonist named Robin Field. Graphics and music are similarly altered to excise any licensed Captain Tsubasa material, leaving a game that resembles the original only in play mechanics. Instead of directing controlling a team, the player chooses options from a menu and watches the results play out while an announcer excitedly describes it all. Team management proves more in-depth than most sports games of the era, and Robin and the other Westernized players mimic the Captain Tsubasa tale of chasing a championship.

Tecmo Cup Soccer's novel take on things failed to catch on. It arrived in 1992, well after the Super NES had eclipsed the original NES as Nintendo's favored system. And while the Captain Tsubasa game was an influential success in Japan, many Americans didn't know what to make of a soccer game played mostly through menus. “A role-playing sports game?” quipped one Nintendo Power critic, “Hit the showers!”

6. STRIDER

Strider technically isn't based on a manga or anime. Capcom and the manga studio Moto Kikaku devised it as a project in three parts: an arcade game, an NES/Famciom game, and a manga series. The arcade game is very much its own thing, but the console game and the manga follow much the same style and storyline: Hiryu, an elite member of the ninja secret agents known as Striders, uncovers an international mind-control conspiracy. The manga lasted long enough for only one volume and a bonus chapter, but it was clearly out to promote the game. The same went for a cassette with the Strider theme song—which appears, minus lyrics, in the NES game's intro. Both the manga and cassette came out only in Japan, which was apparently Capcom's key market for Strider.

Yet the Strider console game didn't come out in Japan. The NES version debuted in America in 1989—minus any help from the manga, of course—but Capcom canceled its Japanese counterpart for reasons never quite clear.

Some point to issues with the game's programming. While the NES Strider is a complex and stylish side-scroller, its gameplay and graphics are choppy and perhaps even unfinished. This theory is partly backed by a leaked prototype of the Japanese version, which is even rougher than the American release.

Many NES titles were developed in Japan but never released there, from Nintendo's own StarTropics to oddities like Bandai's Monster Party and Dynowarz. Strider remains the most perplexing, however: a game with a manga tie-in and kanji on its title screen somehow skipped the Japanese market. Not that the average NES kid knew anything of its origins. For most of us, Strider was just another NES action game with a vague anime look.

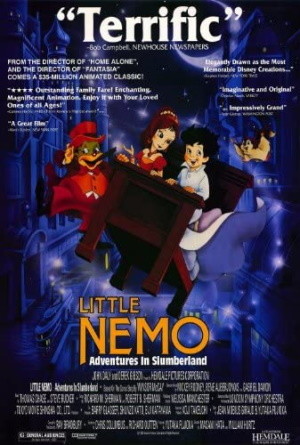

7. LITTLE NEMO

Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland is a film with a complicated past. In development for over a decade, the production courted George Lucas, Ray Bradbury, Moebius, Hayao Miyazaki, Osamu Dezaki, and many others, inspiring multiple pilot films and many discarded drafts before Tokyo Movie Shinsha and director Masami Hata put together an actual movie in 1989. Capcom's Little Nemo titles had more straightforward origins: Capcom licensed Little Nemo, made two different games for the arcade and NES, and released them both in 1990. The end.

There was, however, a catch: the Little Nemo movie didn't actually come out in American until 1992. The box for the NES game doesn't mention the film at all, and gaming magazines of the day referenced Winsor McCay's original comic strip without mentioning a movie that was, at the time, only out in Japan.

Capcom's arcade game is a simple side-scroller that wasn't around for long, but the NES game, Little Nemo: The Dream Master, had greater traction. It lets Nemo feed and commandeer friendly forest animals with different abilities, turning each stage into a puzzle. Only in the final levels does the game adopt the movie's focus and pit Nemo against the Nightmare King.

By the time Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland was in theaters, NES owners were able to figure out what had happened. Then again, it's likely that a few children, unaware of McCay's ancient comic or the movie's history, assumed that they were watching a big-budget animated adaptation of Capcom's NES game.

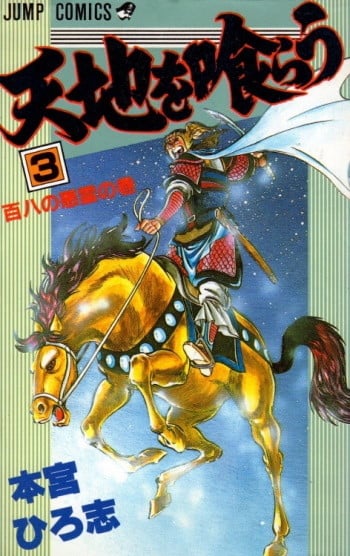

8. DESTINY OF AN EMPEROR

There are an estimated seven million video games based on the Romance of The Three Kingdoms historical novel and the Warring States period that it explores. So even a student of history might assume that Capcom's Destiny of an Emperor NES title is what it appears to be at a glance: an RPG based on the exploits of Liu Bei, Zhang Fei, Guan Yu, and other characters from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

They would be partly right, but Destiny of an Emperor took another step along the way. Someone at Capcom must have dearly loved Hiroshi Motomiya's Tenchi wo Kurau manga series. It lasted seven volumes and never earned an anime adaptation, but Capcom turned it into three arcade brawlers and two Famicom RPGs. The second arcade game was Americanized into Warriors of Fate, and the first RPG appeared on the NES in faithfully localized form as Destiny of an Emperor.

There are hints of Destiny of an Emperor's origins in the copyright and manga-like portraits, but that was beyond the suspicions of many NES players. By this point, they were used to seeing Capcom adapt all sorts of things. This was, after all, the company that turned a ninja action game into a vehicle for the Noid, Claymation mascot for Domino's Pizza.

Releasing Destiny of an Emperor was an risky move for Capcom; the company was better known for action games, and Destiny's method of turning clashes between armies into simple RPG battles went again the grain. If it did well, it wasn't enough to get the second Tenchi wo Kurau RPG out in America.

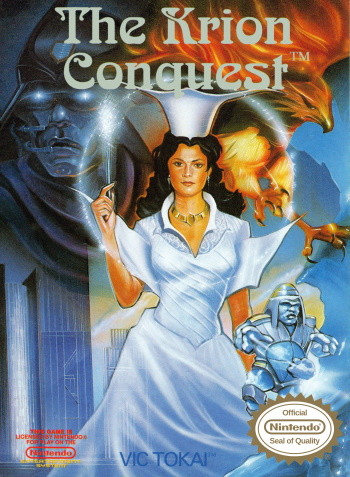

9. THE KRION CONQUEST

Vic Tokai's The Krion Conquest is both an enjoyable action game and a blatant, shameless imitation of Capcom's Mega Man series. The heroine, Francesca, has an arsenal of weapons like Mega Man, faces a horde of robots like Mega Man, and looks like Mega Man in a witch's outfit.

To be fair, The Krion Conquest had inspirations beyond Mega Man. Production staff revealed that the game was initially based on The Wizard of Oz—specifically, the 1986 Japanese-Canadian anime series known as The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. When the rights were off-limits, Vic Tokai switched everything over to an original game about a witch fighting an empire of evil robots, bringing in manga artist Ashika Sakura for the character art. The only remnant is the heroine's Japanese name: Doropie. Well, that and the fact that the American cover could be some offbeat take on Glinda the Good Witch.

Other problems emerged for the game's American release. It came out in Japan as Magical Kids Doropie, but Vic Tokai originally planned to rename it Francesca's Wand, complete with a title screen where the heroine resembles a goth mime more than an anime witch. Such plans went astray, however. Vic Tokai rushed the game to North America with the title The Krion Conquest and removed nearly all of the cutscenes, leaving the game largely plotless and lacking an ending.

Only the introduction remains, and for some reason Francesca's look was altered to be…well, slightly less anime-like. Those extra millimeters of eye socket could've cost Vic Tokai a sale, after all.

The Krion Conquest was perhaps lucky it came out at all. It was Vic Tokai's final NES release, and the rushed American version showed that the company was ready to move to new venues. Other games weren't as fortunate, such as…

10. SECRET TIES

For a true obscurity in anime-based NES games, consider one that nobody actually played. The years of 1991 and 1992 brought a mass extinction for NES titles. Lured to the shiny new territory of the Super NES and Sega Genesis, publishers canceled many NES games, even when they were apparently finished and ready for the market. Among them was Vic Tokai's Secret Ties.

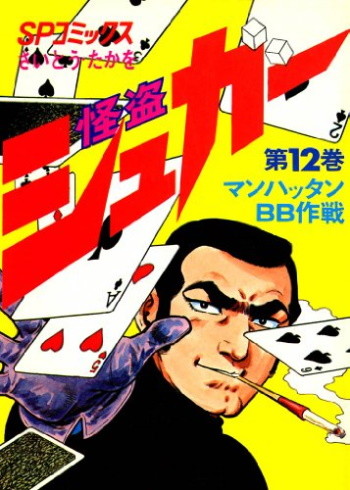

Vic Tokai released two NES games based on Golgo 13, leaving surprisingly amounts of sex and violence intact for American audiences. This led Vic Tokai to take a chance on a lesser-known work of Golgo 13 creator Takao Saito. Though it was reasonably popular in the 1970s, Master Thief Sugar was long dormant by the time Vic Tokai optioned it for an NES game. Still, it's fertile ground for side-scrolling action title. The wisecracking Sugar lands closer to the picaresque tales of Lupin III or Diabolik, though he and Golgo presumably share a barber.

Unlike the multi-genre sniping and mazes of the Golgo 13 games, Secret Ties is a straightforward and serviceable action game with catchy music and a tale of captured girlfriends and ancient civilizations. Wary of the marketability of a hero called Sugar, Vic Tokai renamed him “Silk” for reasons known only to them. Such concerns didn't matter in the end, because Secret Ties became yet another casualty of the NES Apocalypse. The game was finished, with box art and everything, but Vic Tokai just didn't see a profit in releasing it.

Secret Ties eventually surfaced through The Lost Levels, a website dedicated to discovering unreleased games, and that puts it in luckier straits than many other canceled NES games. A lot of them simply vanished without a trace, including Vic Tokai's own Shogun Maeda and Mariner's Run. Perhaps NES audiences of 1992 wouldn't care that much about Secret Ties, but it would've been the most anyone cared about Master Thief Sugar since the 1970s.

The questionable art of remaking or disguising anime-based games didn't end with the NES, and it continued through the next generation in games like Mystic Defender and U.N. Squadron. Yet it's a lost art today, when no publisher would bother effacing a game's anime roots. At most, you can hold out hope that Namco Bandai will sneak Chubby Cherub into the next Dragon Ball fighting game. Ask them nicely.

discuss this in the forum (25 posts) |