Review

by Andrew Osmond,| Synopsis: |  |

||

Stephen Alpert, the only non-Japanese member of Studio Ghibli, remembers the days when he fought to sell Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, and the studio's other classics to the world. He focuses especially on his dealings with Disney and Miramax, contending with executives and marketers baffled by Ghibli's films, including the monstrous Harvey Weinstein. |

|||

| Review: | |||

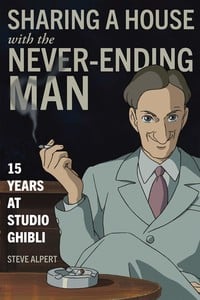

Stephen Alpert (by-lined as Steve Alpert here) used to be a man of mystery, the Westerner at the fabled Studio Ghibli. Alpert even played a man of mystery in Ghibli's The Wind Rises, voicing the spy Castorp in Japanese, who loves meeting interesting people, enjoys fine dining and knows state secrets. Castorp is pictured on the cover of Alpert's wonderful memoir, Sharing a House With the Never-Ending Man, published in English by Stone Bridge Press. (It was previously published in Japanese under the title I am a Gaijin: The Man Who Sold Ghibli to the World; that edition had Alpert and his Ghibli colleagues in a group with John Lasseter on the cover, which would look awkward now.) The real Alpert isn't a spy, but interesting people, fine dining and high-level secrets figure heavily in his book. As an American in Japan, Alpert was hired by Ghibli president Toshio Suzuki in 1996, just when the studio was gearing up for a new phase in its history. Some Ghibli films were sold overseas previously – who can forget that Totoro was first distributed in America by the schlock studio Troma? – but now Suzuki and his boss, the terrifyingly capricious magnate Yasuyoshi Tokuma, wanted higher-powered clients. Three months before Alpert was hired, Ghibli announced that its films would be distributed internationally by Disney. The book focuses on the next few years, when Ghibli was releasing Hayao Miyazaki's blockbusters Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away. Alpert was a senior director at Ghibli, a member of its board of directors, and the leader of a newly-established company division, Tokuma International. He takes us with him around the world, sometimes helping out the Ghibli staff, sometimes being the Western face of Ghibli. He witnesses raging arguments, studio meltdowns and the up-close screaming visage of an unhinged Harvey Weinstein, ranting that he'll cut Mononoke by a half-hour or else. Alpert is in the room when Michael O. Johnson, the Disney exec who signed the deal with Ghibli, gets his first view of Princess Mononoke, which he'd bought unseen and unmade. The footage is full of severed heads and arms and a princess who not only doesn't sing but who spits blood. Johnson, Alpert notes, is speechless. Later he begs Suzuki to add something nice to the trailer, for heaven's sake! How about a kiss? (Suzuki manages to fake something; if you've seen Princess Mononoke, you may guess how.) Much later, when the sound mix for the English dub is being prepared, Alpert visits a New York sound studio with terrible elevators, where a Miramax technician demonstrates how he'll “revise” the film. It's the scene where Ashitaka first comes to the Deer God's pond in the heart of the holy forest. It's a hushed, reverent sequence – far too quiet, in the technician's judgement. He shows his preferred version, complete with added wind, butterfly noises, tree noises, and funky alien effects for the glimpsed Deer God. Don't you wish you could see such an artistic train-wreck? Maybe it'll be an extra on a future special edition. It's also Alpert, a few years later, who must take the stage for Spirited Away's first international award. It's the Golden Bear, the highest award at the Berlin Film Festival. It's easy to find an online video clip of the moment, with Alpert as Ghibli's face to the world. It looks pretty normal, but after reading Alpert's account, you'll be studying the footage more closely. You remember that mishap with Justin Timberlake and Janet Jackson at the Super Bowl? Alpert claimed something similar happened on the festival stage, “though I did end up with the Bear and not a slap in the face.” Such episodes can feel like Benny Hill, or else they can rise up to high comedy. Alpert's bewildered appearance on late-night Japanese TV smacks of Bill Murray in Lost in Translation. An episode in Britain, where a frantic Alpert is appallingly rude to an innocent sales clerk (“Will you please just ring up these ****ing shoes!”), is worthy of vintage John Cleese. One chapter, about Japanese funerals, sounds sombre, but it becomes a priceless comic farce, with guest appearances from Japanese movie stars, a very angry widow, and even a slapstick scene with the Prime Minister. The book also has, however, rather a surplus of references to Alpert noting attractive underdressed women. There's such a thing as too much candour. Of the characters, we see a lot of Suzuki and Miyazaki through Alpert's eyes (Isao Takahata is barely glimpsed). We learn that Alpert might have been killed by Suzuki's in-car entertainment system, and how Miyazaki was once invited to meet Martin Scorsese, responding with all the enthusiasm that Scorsese shows toward superheroes – that is, none. (“Does he understand what a big deal this is?” begs a publicist, vainly.) But a more overbearing presence than Miyazaki in the book is Yasuyoshi Tokuma, the head of Ghibli's parent company Tokuma Shoten. He comes over like a yakuza honcho crossed with Rupert Murdoch, in a Bond-villain lair overlooking Tokyo harbour. Yet Alpert ends up regarding him with true affection. The other predominant presence in the book is Disney. Old-time anime fans who followed the Disney-Ghibli deal closely feared that the Mouse would be clueless about handling the films. Many of those fans will feel vindicated by Alpert's revelations, including his confirmation that Disney executives were inclined to “bury” many of Ghibli's films, never releasing them in most territories. Alpert explains that the Disney people who made the actual deal, including Michael O. Johnson, knew and valued Ghibli's films and most certainly wanted them released worldwide. Many other Disney executives, however, disagreed. Some anime fans insisted Disney planned to bury Ghibli to dispose of a rival, as if the executives feared that the Americans going to see Mulan would have suddenly switched to Princess Mononoke instead. Alpert, though, highlights how incomprehensible Princess Mononoke seemed to Hollywood pros. As the earlier sound studio anecdote shows, the film was judged way too quiet (“They insisted people would yell at the projectionist, “SOUND!”). The Disney staff wanted to know if the Deer God was a good god or a bad god. Going through Ghibli's backlist, they objected to all the things you'd guess that they'd object to – tanuki testes in Pom Poko, menstruation references in Only Yesterday, flesh-colored pants in Nausicaa. Disney just wasn't on the same page as Ghibli. There's a wonderful scene in which Suzuki explains the mechanics of the flying in Kiki's Delivery Service to a roomful of Disney marketers, while they gape at him in incomprehension. Hollywood animators, on the other hand, would have got Suzuki's point instantly. We get a good idea of animation at the end of the 90s, with visits to Disney, Pixar, Fox (then making Anastasia), and Aardman. Alpert tells us about a crucial preview screening of Spirited Away at Disney, which would determine how it was marketed in America. Following the advice of Lasseter, Alpert strove to pack the screening with Disney animators, who would have cheered Spirited Away. But alas, the screening was crowded out by studio executives, who dismissed Spirited as “a tiny art house film.” The chapters between the comedy highlights can be dry, but still hugely enlightening. Alpert gives us whistlestop tours of Asia, where he finds pirated copies of Princess Mononoke gracing the TV screens in every downtown electronics store in Seoul. We're swept to the peaks of entertainment glamour, as Alpert treads the red carpet on Oscar night, and then down to the cramped depths of the Cannes Film Market, where he learns the worst-dressed rep can be the man to do business with. There's loads on Japan's own business culture, which can seem ludicrously irrational until Alpert reveals the methods to its madness. It's a splendid book, although I caught two errors worth noting. One is a passing reference to Britain's Charles and Diana attending the funeral of the Emperor Hirohito in 1989. In fact they weren't there (the Queen's husband Prince Philip attended instead), though they'd visited Hirohito three years previously. A more anime-relevant slip relates to an altercation Alpert had with an incredibly obnoxious New York Times journalist, who demanded a one-to-one interview with Miyazaki, tomorrow. When Alpert, understandably, lost patience with the rude request, the hack took his revenge in a huffy article which slurred Japanese people as manga-reading illiterates and caused a minor uproar. Alpert says the incident happened during the international release of Princess Mononoke. In fact, it happened during the roll-out of Spirited Away in 2002, as reported by Anime News Network at the time. |

|

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of Anime News Network, its employees, owners, or sponsors.

|

| Grade: | |||

Overall : A-

+ A massively informative book on Studio Ghibli's pivotal years, with sublime comedy moments. |

|||

| discuss this in the forum (11 posts) | | |||