The Winter 2021 Manga Guide

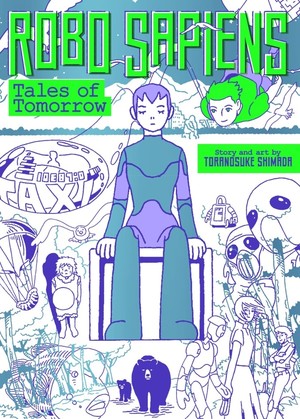

Robo Sapiens: Tales of Tomorrow

What's It About?

In the future, robots are more than machines. Autonomous “cyber-persons” with A.I. brains are part of society, interacting with humans and growing their own culture. In fact, they may be surpassing humans, as biological homo sapiens and their own world have begun to die out. But are humans truly disappearing, or are robots the new “humans”? This speculative science fiction tale of interconnected stories was awarded the Division Grand Prize at the 2020 Japan Media Arts Festival. (from Seven Seas)

In the future, robots are more than machines. Autonomous “cyber-persons” with A.I. brains are part of society, interacting with humans and growing their own culture. In fact, they may be surpassing humans, as biological homo sapiens and their own world have begun to die out. But are humans truly disappearing, or are robots the new “humans”? This speculative science fiction tale of interconnected stories was awarded the Division Grand Prize at the 2020 Japan Media Arts Festival. (from Seven Seas)Robo Sapiens: Tales of Tomorrow is scripted and drawn by Toranosuke Shimada and Seven Seas Entertainment will release the first omnibus of this manga on December 7

Is It Worth Reading?

Christopher Farris

Rating:

Unlike most mecha series which are all about the characters, this one focuses on the robots! Okay, that's not an entirely accurate assessment of Toranosuke Shimada's Robo Sapiens, but I just could not resist the opportunity handed to me by the premise. And it feels like an appropriate enough sentiment to start off with, since this manga's most appreciable element, to me, is its willingness to head in less common directions with its subject matter.

Of course, before you even find yourself getting taken in by the story and conceptual content of Robo Sapiens, it's almost certainly the art that will catch your attention first. Sporting a deceptively simple style that could arguably be described as influenced by older, 'classic' manga titles, the artwork on these pages trades in contrasting geometry: Simple circular shapes of people, robots, and vehicles transposed against the sharp square edges of cityscapes, picked out with bold blocky text integrated into so much of what we're shown. It's immediately striking in its deployment, which gives way to subtle rewards as the manga goes on, and the background and layouts seem to become sparser and simpler, in time with the quiet, eternal expansion of the story's broadening scope. The detail on display here is simple, yes, but that doesn't make it lesser— rather, Shimada leverages this appearance to make every little bit added or subtracted to the characters count as time is shown to pass by.

The core of what makes Robo Sapiens so unique is the use of time in the story. I can't lie: I've long grown weary of more 'typical' stories of robot/human integration where the mechanical beings are used as stand-ins for social questions of rights, prejudice, and so forth. Robo Sapiens thankfully skips over that component almost entirely; it opens with a chapter which feels like a stand-alone parable in an anthology, only to add more characters and corners to its universe and coalesce them together over a tremendous amount of in-series time. This is all to arrive at even broader existential questions: What does the integration of robots into humanity mean for the definitions of both those groups? How does existence itself look to beings who are effectively immortal? It makes the overall series feel genuinely 'speculative' in the spirit of classical science-fiction without getting too bogged down in explicit technological details. There are moments in this self-contained volume that could springboard into entire storylines themselves, and as such, some story elements or twists here can come off under-explained. But overall, its art and story work together to make Robo Sapiens a lovingly unique work of sci-fi manga.

Rebecca Silverman

Rating:

Really good science fiction, I've always thought, ought to make us think seriously about both the past and the future. That's why Ray Bradbury's books are so successful – they make you think not only “we could end up there” but also “how did we get to this point?” Toranosuke Shimada's Robo Sapiens does much the same thing, albeit without the horror component of many of Bradbury's works; it takes us on a journey to a future that at times looks awfully like the past and makes us wonder if we're heading for that point as well.

Part of why it works so beautifully is because of the way Shimada writes the robots. They're not the usual, well, robotic artificial beings that we more often see; they're more like cyborgs, even though they appear to be fully mechanical rather than augmented humans. In other words, they are true androids in that they really do seem to be a separate race – the eponymous “Robosapiens.” Even though they have some mannerisms that are more mechanical and are fully aware of their created status, they're also remarkably human, something that grows the more time passes in the story. It covers millennia, opening not too far from where we are now and ending after humanity has basically reset – destroyed itself and returned to a more primitive (for a given value thereof) state. This in itself is fascinating because one of the four main robots the story follows, Maria, spends one chapter peeking in on human evolution. That the book ends with her completing her final mission for humanity, protecting an underground vault of nuclear waste, and then seeing a child like the caveman child she watched millions of years ago, is a lovely bit of bookending, especially since her consciousness leaves the earth with all the robots who have come before her, returning it to humans until they once again develop the technology to create robots.

It's really a bit difficult to describe what makes this omnibus so striking. Certainly the cyclical feel of it, the sense of “the more things change the more they stay the same” is a prime example; the book opens with an old man searching for his robotic wife without realizing that he became her at some point, and the final mission of Sachio, a “freedroid” (roaming robot who helps whenever needed) returns us to that character, much like Maria returns to the cave child. The last scenes in the book also bring us to that idea of a cycle of life, and the ultimate destruction of Sachio, Maria, and the other two robot protagonists, Toby and Chloe, is less sad than inevitable in a sort of ephemeral way. The plain, blocky art, which incorporates words into itself (and Seven Seas' translation does a great job with this) runs the risk of feeling too simple, but ultimately isn't, instead allowing us the space to appreciate the world and the characters' emotions, even if the characters themselves don't always understand that they have them.

Even though it's about robots, at the end of the day I think Robo Sapiens is really about being human without an expiration date. I'm not sure if that makes sense. But I do hope you'll read the book.

Grant Jones

Rating:

Robo Sapiens is powerful fiction. It conjures up some of the same feelings I felt as a little boy watching the sci-fi anthology Robot Carnival for the first time. There are musings on life and death, time and love, and how change comes for us all in the end – and so do new beginnings.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. Calling Robo Sapiens an anthology is only half the story. It feels more like flipping through a photo album of someone's life, seeing familiar faces change over time as characters enter and leave at irregular intervals. It is a tale of artificial life created by fickle human beings, and while these creations are somewhat emotionally colder than their creators – and certainly more long-lived – they are ultimately subject to the same considerations as their creators.

Where Robo Sapiens truly shines is in its ruminations on the idea of time, which is heavily present in the volume's central story of a robot created to monitor radioactive waste until the stockpile becomes safely inert. The interval between check-ins grows from weekly, to monthly, to annually until a time many centuries in the future when all is well. Of course things go awry, but it's never fully explained what went wrong in the background. Other than the gradually degrading demeanor of the techs checking on the robot – and eventually their complete absence – the reader gets few details as to the state of the outside world. Future visitors bring news of terrible catastrophes, devastating wars, and robot advancement, but even these are mere blips breaking up long periods of lonely emptiness.

Ultimately though, this is a story about human relationships (as most tales are). Now nearing our second anniversary of a global pandemic, one in which lockdowns and isolation have become frequent companions for many of us, it is easy to relate to the periods of quiet solitude and the contemplative musings on the outside world. As world-changing events happen beyond our windows and walls, we return to our duty again and again – some at keyboards, others at checkout lines, but all increasingly isolated by literal distance or the fault lines of socio-political unrest. The robot characters of Robo Sapiens also make plans for long-distant, undreamed of futures, wondering if their paths will ever intersect again. For all its depiction of inhuman subjects, it is a strikingly relatable tale.

But what struck me most of all was the sense of melancholic joy that suffuses the volume. Robo Sapiens is certainly not an upbeat story, and it delivers news of humanity's continual decline over the years with detached, machine-like regularity. Yet I would not call it pessimistic either. There is a sense that humanity ultimately endures through its creations – even the inhuman robotic machines meant to surpass us. Love, hope, knowledge, the promise of future generations – these all survive. Sure, they are twisted and morphed by the ravages of times, but perhaps the message of Robo Sapiens is exactly that: In the end, humans suffer because of human action, and humans persevere by the same hands. We endure. Sadly at times, lonely at others, but ultimately we endure, and there is a wonderful beauty in that battered survival.

discuss this in the forum (36 posts) |

back to The Winter 2021 Manga Guide

Feature homepage / archives