Hero of a Lost Era: Examining the Context of Kamen Rider Kuuga

by Coop Bicknell,The following article contains major spoilers for Kamen Rider Kuuga

Art is most often a response to the world it was made in. Sometimes that response might be a light remark, and other times, it's a loud scream. 2000's Kamen Rider Kuuga is one of those screams, directed explicitly at the string of misfortune and tragedy that befell Japan in the 1990s, a period known as its “Lost Decade.” Having first viewed the series when it officially hit streaming in 2020, Kuuga captivated me with its portrayal of people doing their best to carry on despite the world becoming scarier by the day. A feeling that many strongly relate to in current times.

What follows is a macro-level examination of what Kamen Rider Kuuga scratches at with its commentary. In addition to these larger ideas, the series is permeated with many more micro-level observations throughout its 49-episode run. I would appreciate you checking it out for yourself. Major spoilers ahead.

Kamen Rider Kuuga follows adventurer Yusuke Godai, who is dragged into humanity's struggle for survival against the Grongi, ancient monsters who can disguise themselves as humans. With detective Kaoru Ichijo behind him, the two men later learn that the Grongi's attacks are less random than they initially thought. In fact, it's been a game from the beginning. This death game, known as the Gegeru, depicts its players as a cult of serial killers through the horrific rules they kill by.

For many working on the series and its sponsors, the real-life parallels were too close for comfort, even when the death game was still a mystery to the audience. The Grongi quickly became an analogy for the cult fears that swept Japan following the events on March 20, 1995. The cult Aum Shinrikyo released sarin gas into Tokyo's subway system, killing 14 and injuring thousands. The authorities had been tipped off to the attack, but the slow response made the public increasingly anxious about what could happen next. This tragedy dissuaded Toei from using an evil organization like the original Kamen Rider's Shocker as Kuuga's villains, but it ended up being inescapable.

Anxious himself, chief producer Shigenori Takatera couldn't make just another children's show. He wanted to find a way to live with those anxieties through his work.

“I think it's about what kind of anguish people live with, and how they [the main characters] can heal it by interacting with it,” he stated in an official press conference for the series in 2000.

With that in mind, Takatera and series scribe Naruhisa Arakawa intended to hold up a mirror to many more of the country's anxieties. At the time, cult fears were on the minds of many as another compounding element that made a rough decade even more difficult.

The Lost Decade started with the burst of Japan's prosperous bubble economy in February of 1991. The stock market started to decline the year before, soon turning loans used to purchase real estate into bad debts. Why “bad” debts? The land was often used as collateral, so its plummeting value could not cover the defaulted loans. The banks were buckling. Japan's economic situation improved slightly by 1996, but the economic reforms enacted in March 1997 had disastrous consequences. By the fall of 1997, many large financial institutions went bust in an event known as “the credit crunch.” With another steep drop in the stock market, the public became understandably uneasy. Employees of all ages were being laid off left and right across the decade, with unemployment taking a steep jump after 1997. 1999's unemployment numbers would surpass those of the United States. Young workers were increasingly fed up with the poor working conditions, while older workers had the rug pulled out from under them. Entering the new millennium, the public was terrified that whatever stability they had was now unguaranteed for future generations.

Kuuga approaches these worries for the future with the recurring character of Mr. Kanzaki. The tenured elementary school teacher struggles with his role as an educator when the audience first meets him. Talking with a coworker, he questions if kids these days are too spoiled to get through real hardship—a question also posed by Takatera and Arakawa in their mission statement for the series, interestingly enough. However, this rough exterior is broken while waiting to meet with Godai. Mr. Kanzaki breaks down as he questions what he can actually do for his students. Can he point them in the direction of achieving rich and fulfilling lives despite the pressures put upon them by society? Is stable employment possible for them? Or is the world he's sending his students out into going to be terrifying regardless of the Grongi?

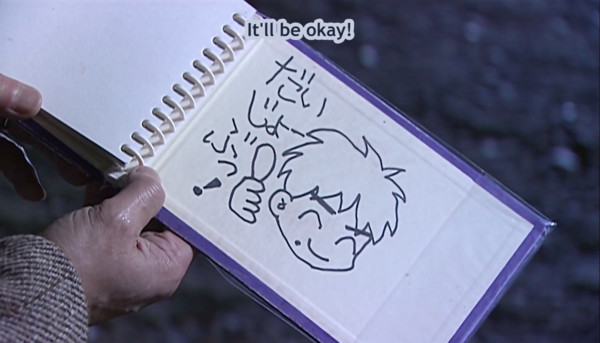

These are questions teachers ask themselves often, both then and now. Godai is a vehicle to assuage those fears for real-life educators and this fictional one. Mr. Kanzaki is moved to tears upon learning that his student took his words to heart, striving to be his best to help others. The enthusiastic thumbs up Godai gives Kanzaki, something he taught his student, is a sign that he made a difference, that maybe his kids will be alright.

Unfortunately, that kind of support system is never guaranteed, leaving room for others to slip through the cracks. Chono has never had a Mr. Kanzaki-like figure in his life. With his slim prospects for the future becoming slimmer by a severe illness, Chono somehow finds the Grongi very appealing, as if their way of life was some future where he could find common understanding among his would-be peers. Real-life cults attract potential members by preying on their lack of faith in the world, with promises that the cult could bring them some new kind of spiritual interiority that the material world could not. It could all start with a seemingly friendly face inviting you to some function.

Hoping to fall in with Grongi, Chono fashions himself in clothing not too far off from the counter-cultural stylings of the disguised Grongi, including a tattoo that resembles one of their brands, which is considered quite taboo in Japanese culture. Chono is fortunate to quickly realize that his would-be peers don't want any understanding from him—they want him dead. When the viewer is introduced to him, he is mistaken for a Grongi. Ichijo does the same thing, which begs the question: if the police thought this kid was Grongi, reasonably, anyone would. Following the sarin gas attacks, the Japanese public took a long, hard look at why someone might join a cult, fueling fears that anyone could be a cultist—or in the case of Kuuga, a Grongi.

Midway through the series, Godai's sister, Minori, and her pregnant co-worker, Keiko, tag along with his friends to a water park. Sitting poolside with Minori, Keiko shares her worries for her unborn child. Will her child be born into a safer world? Minori has no real answers to console her with before they leave the park. As the group exits, a new guest walks in right past them on their way out. Shortly after arriving at Keiko's apartment, Minori turns on the television to discover that the water park was attacked soon after they left. Realizing it could have been her baby, Keiko faints. Minori later checks with the rest of their group over the phone, confirming their collective fear with each other: “It could have been me.” It's a fear that permeates the day-to-day of the cast. I would be lying if the idea wasn't often on my mind, either.

“Will someone be there to help?” is an accompanying concern to that fear. Two months before the sarin gas attack in Tokyo, another tragedy had the Japanese public asking that question of their authorities.

January 17, 1995. A 7.2 Earthquake hit Kobe, resulting in over 6,000 deaths, US$100 billion in damages, and thousands of people displaced from their homes. To the understandable frustration of many, the government took a measured approach in its response. Foreign aid was selectively accepted, but the government admitted that local governments were too overwhelmed to mobilize foreign search-and-rescue teams effectively. In the meantime, non-profit organizations brought droves of student volunteers to help people on the ground. NPOs were not the only groups involved, as the Yakuza arrived to open soup kitchens and contribute aid. This wouldn't be the first or last time the crime organization would be some of the first on the scene either. They later assisted during the earthquake and preceding tsunami that hit Fukushima in 2011.

Between the two tragedies of 1995, the Japanese public had little confidence in the government to take swift and effective action should something similar happen again. Naturally, those government first responders included the police. Already notorious for covering up corruption for politicians and within their own ranks, it became even more concerning when they allegedly botched investigations simultaneously. These concerns led to a police reform council in 2000 to address standards, practices, and approaches to their internal affairs. However, regardless of any actual reform that may have taken place, it didn't help the public's relationship with the police.

In response to that, Kuuga's realistic depiction of Japan made its viewers ask a reasonable question:

“If that was the response to those real-life tragedies, could the police do anything in the face of these brutal monster attacks?”

Though sympathetic to Ichijo and his colleagues, the opening cour of Kuuga hammers home that the police are helpless against the Grongi. Any offense against the Grongi will result in officers losing their lives. The police can't quickly figure out the Grongi's play either, leading to more deaths. Godai ends up being the only person who can fight back, and he happens to be at the wrong place at the right time. That doesn't mean that the police trust him immediately, as Ichijo eventually has to play some politics to officially bring Godai on board the investigation.

In the last quarter of the series, we learn that the source of Godai's power may be turning him into something as monstrous as the Grongi. He continues fighting to protect others despite his conflicted feelings about resorting to violence. This follows the key conceit of Kamen Rider: a monster who fights those like him to protect the humanity he no longer has. Ichijo has that same realization: he, too, as a police officer, is a monster. When involved in a criminal situation after almost a year of fighting the Grongi exclusively, he feels an incredible sense of unease when firing upon another human being. Ichijo faces the violent reality of his profession, making him no better than the Grongi. However, like Godai, he will do what he can to help others.

Over 20 years later, Kamen Rider Kuuga continues to spark these conversations in the East and now the West. The series paints a picture of a nation trying its best to move forward despite the continued tragedy they face daily, something that the crew behind Kuuga was all too familiar with. As I mentioned initially, it's hard not to relate to that as we look at our own day-in and day-out tragedies. Kuuga touches on topics that will remain relevant in Japan and the rest of the world. With the series continuing to run on streaming services and its recent Blu-ray release, I hope that people can take away one thing from it at the very least: Life is rough, but if we try to carry on and help each other as best we can, we might be okay.

Special Thanks to Chiaki Hirai and Mike Dent for their insights on this piece.

Coop Bicknell is an occasional writer and co-host of the podcast Dude, You Remember Macross? You can follow him @RiderStrike on Twitter.

discuss this in the forum (6 posts) |