The Mike Toole Show

The Hard Cel

by Michael Toole,

If you go to the top of this page and click on the VIEWS tab, you'll get a list of columns on the site, including my own, with descriptions. My column is specifically described as "a look behind the scenes at the fascinating history of anime productions." That amuses me, a bit, because it's not strictly accurate – my stuff is about my experiences as a fan as often as it is about anime itself. Now is one of those times where I'm going to go ahead and mix up those two aspects of my column - how anime is produced, and my life as a fan - in a hobby that alchemically combines the two. I'm talking about cels and cel collecting.

If you're a serious animation fan, you'll know right away that cel refers to cellulose acetate, the plastic stuff where animators throw down ink and paint that turns into wonderful entertainment for You and Me. Cels have been in use for animation almost since the inception of the medium, though the earliest animators used actual celluloid (the hilariously flammable stuff that was used to create film). Interestingly, many of Japan's early animation masters weren't able to use cels, because getting the acetate was too expensive, so they settled for paper. (You can see some of these paper-animated cartoons on the Roots of Anime DVD from Zakka Films.) But after World War II, cel animation became ubiquitous all over Japan.

Here's the thing about traditional cel animation: it's a complex, assembly-line practice that requires many, many expert artists and leaves behind intimidatingly large piles of by-product, both paper and acetate. We human beings are pack-rats by nature, so it wasn't long before animation and comic fans began to seek out these leftovers of the production process for themselves. Now, to be fair, most of these cels are pretty pedestrian; they're small shots of big characters, or they're scenery, or they're Itchy's arm instead of his whole body. But many cels are instantly recognizable (and thus instantly desirable), and a select few, especially when combined fully with original props and background elements, are good enough to hang in a damn art gallery.

I didn't care about cel collecting when I first noticed it, because it seemed like a lavishly expensive hobby to me. This is because all of the good cels of the most popular series (and I was only really familiar with popular stuff in 1995 and 1996) were expensive. There was just no way you were getting a close-up of Shampoo from Ranma 1/2, impishly smiling, with both eyes open, for less than a hundred bucks. And Studio Ghibli cels? Pshaw, forget it! The good stuff was stratospherically expensive, and even the tiny, smudged shots of Totoro's Mei and Satsuki from far away approached $100 each.

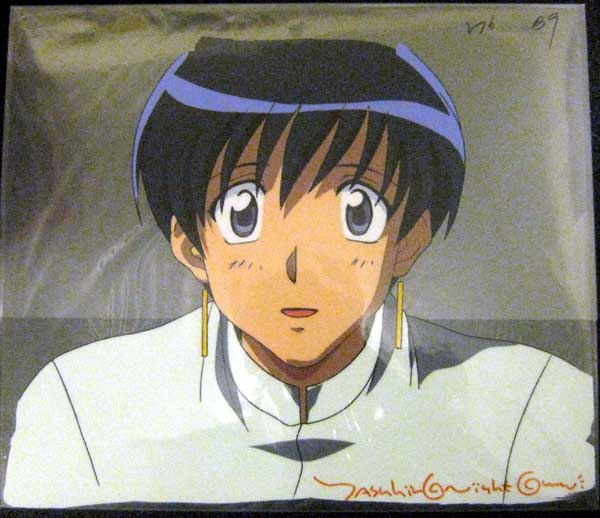

Things changed in 1999, when I visited Japan. Anime cels were as common as dirt there, and while the good stuff still had hefty price tags, there was a certain importer's markup that wasn't present anymore, making a lot of goodies tantalizingly within reach. Even better, the viciously rapid rise and fall of shows meant that a lot of old favorites that were still well-liked in the West had been forgotten in Japan. That explains how I got my first cel, a shot of a show's main character with both eyes open, looking at the camera, for 450 yen. Now, that character may have been Chirico Cuvie and the show might have been Armored Trooper Votoms, which has never been overwhelmingly popular even in the best of times, but right from the start, I was hooked. Before the afternoon was up, I'd bagged a broad selection of cels from Giant Robo, Battle Athletes, GoShogun, and Black Jack, all for under 1000 yen each. Big favorites like Sailor Moon, Fushigi Yuugi, and Rurouni Kenshin were also surprisingly affordable, but I wasn't quite ready to take that plunge.

See, there's a learning curve to cel collecting. The most valuable cels are ones that feature the most popular characters, face front, with eyes open. The eyes-open thing is very important! Sailor Mercury is the perennial favorite of the Sailor Scouts in Japan, but a shot of her with her eyes closed or obscured is likely to fetch less than half of a portrait-style shot of her with her peepers uncovered. Girl characters are always in more demand than boy characters. Some collectors prize oversized cels used for panning shots; others patiently sniff out cels with revealing mistakes or off-model characters. A lot of cels feature multiple layers, with different elements on each one. Over time, these layers get stuck together, or get stuck to their backing paper, so cels that don't have that problem are highly prized. Some cels look about 90% awesome but have paint damage that will leap off the page to a seasoned, discerning collector.

But ultimately, for me, it's an amazing feeling to own an actual piece of an entertainment work that I love. It gives me a greater appreciation for the artistry of the work, it makes me feel more invested in my favorite shows, and it helps me feel closer to the people who created them. There's another big perk to cel collecting, too - it will teach you more about the actual process of animating in Japan than you ever thought you would learn. I can't draw a straight line, but I'm at least passingly familiar with every phase of the actual creation of the animation itself. That knowledge came to me entirely though cel collecting, because it's impossible to just get cels - the cels come packaged with pencil test drawings, or rough animatic sheets, or layout and correction notes, or timing sheets, or even copies of storyboard and character design sheets. You simply cannot have cels without the stuff that leads to the cels. Here's a quick rundown of how it all works.

Okay, so the first thing that gets taken care of in an anime series is the concept, screenplay, and script. That's the theory, anyway; I've definitely seen some anime that seem like the script was the last thing on the checklist. Er, so once that very basic world-building stuff is established, two things happen. First of all, one of the head honcho animators (often the director himself) will create storyboards for the show. These are exactly like Western storyboards, rough drawings intended to tell a simplified version of a story with text descriptions on the side. It can take anywhere from eight or ten days to a few weeks to storyboard a single episode of an anime series. Even as the storyboards are being developed, the series director and head artists are also working together to establish the show's visual continuity - character designs, architecture, mechanical design, proportions, and all that good stuff. Once that groundwork is laid, the actual drawing starts up in earnest.

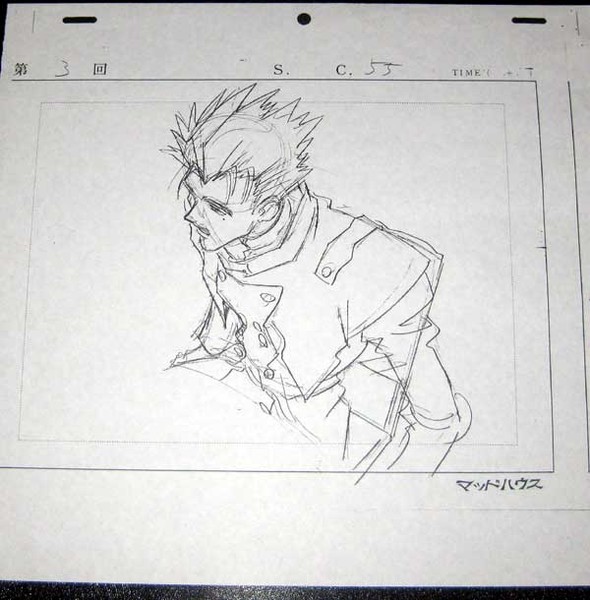

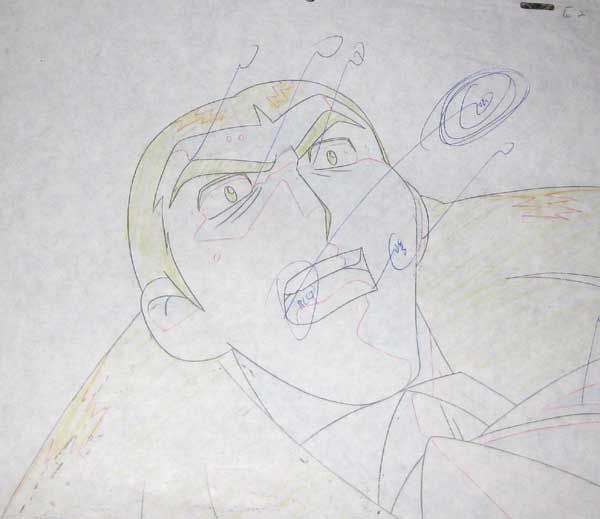

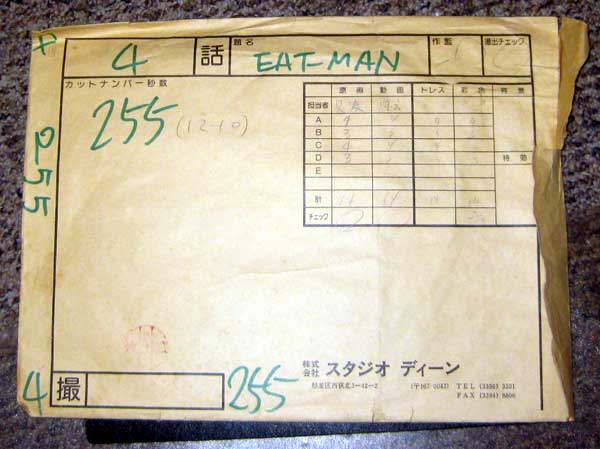

The first step is to create detailed, but very rough pencil animatics (test animation) based on the storyboards. Again, these are often handled by the senior staff to give people downstream a good, solid guide for how the scenes and characters will look. These are called layouts, and are usually a pretty good approximation of how the final cels actually end up looking. They are immensely valuable both to the animation pit crew and to ancillary parties like the sound director, who will use the layouts to determine how to tweak the script for timing. After a couple of rounds of corrections (often done on yellow or blue paper), these images are generally refined enough to be called genga, or key frames for the final pencil animation. Scenes are then divvied up by cut (just as in film, a 'cut' of animation is a single unbroken scene without the camera changing angle or focus - most TV anime has more than 200 cuts per episode!), tossed into a happy yellow envelope called a 'cut bag', and sent out to in-betweeners. (This particular process is detailed in Animation Runner Kuromi, which you should watch right here on ANN because it's awesome!) The in-betweeners and their supervisors will use the tools provided to them - storyboards, rough pencils, and refined genga - to create douga, the "tweens" that create the skeletal framework of the final product. Once a final, smooth, satisfactory test animation is in the can, then the stuff gets colored in with ink and paint and beautiful backgrounds are whipped up - though nowadays the ink and paint are purely digital.

You might be gasping in incomprehension right now, but trust me, you will learn this stuff from the first moment you pull out what looks like a scribbly xeroxed drawing of your new cel from the bottom of the bag. You'll learn about key cels, and book cels, and all the weird numbers and abbreviations along the top of the cel. You'll learn that genga are really beautiful pencil drawings, almost as good as cels sometimes, but they usually don't make it into your hands. You'll figure out that the really nice promotional artwork that ran in OUT and NEWTYPE and ANIMAGE throughout the 80s and 90s was actually a kind of cel called a hanken mono, a copyrighted work created specifically as cover or promo art. (These things are amazing - they're usually HUUUGE! - and pricey. Have a good gander at the old ADV Films box release of the Dirty Pair OAVs for a close look at one. You can see the tape marks at the top!) Then you'll start to notice even more weird stuff, like how anime studios occasionally sell commissioned reproductions of cels from popular shows - Evangelion has been milking this racket for years. You'll discover that sometimes that really beautiful cel is a pretty good counterfeit. You'll realize that background art is incredibly hard to find, so cels are often mated with unrelated but similar background artwork to make them more attractive, or matted with laser-copied background art. You'll find out that most cels that flood into the buyers' market are rescued from the trash, or sold off by the pound by their disinterested studios, or stacks of artwork given to grunt animators, who then sell them in a bid to make up for their lousy wages. You'll even discover that sometimes, cels are just stolen from the studios outright. A lot of Evangelion cels were stolen. Same with Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust. It happens!

The final thing you'll learn is that cel collecting is slowly but surely dying. I still like them a lot, but I haven't bought a new cel in a pretty long time, simply because they don't make them anymore. A lot of studios do still use pencils to create layouts and genga and sometimes even douga, but these items can be frustratingly hard to track down. No anime studio still uses cels - even Studio Ghibli has shifted away from acetate - so the supply, and naturally the interest, is dwindling. But the hobby is still vital and interesting, and like I've said, it will give you a window into how the anime industry worked - and how, in many ways, it continues to work.

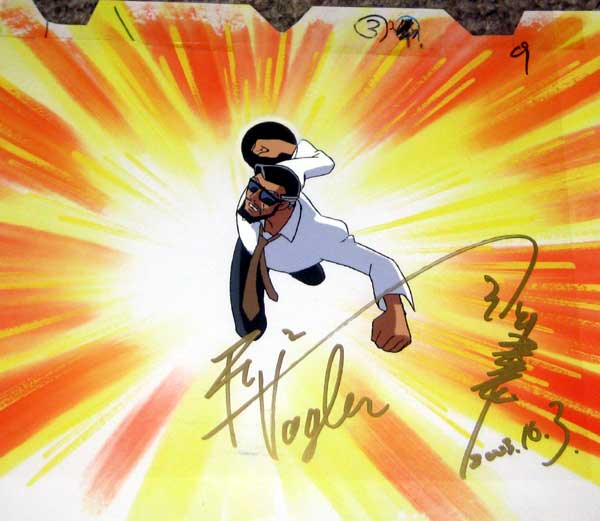

I still treasure my cels and enjoy looking at them, so I thought I'd give you a chance to look at them too. Supplemental to this column is a 15-minute featurette that showcases much of my collection and sheds some light on how the cels fit together with the rough drawings that they come from. My cels are valuable to me because they are so often signature moments of my favorite shows - having them is like owning a prop from a movie, a first edition hardcover personalized by the author, a sketch from the guy that draws your favorite comics, a match-worn shirt from your favorite athlete. Don't miss claiming one if you get the chance!

discuss this in the forum (33 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history