The Real Yokai of DAN DA DAN Part Two

by Zack Davisson,

“Spirits, Paranormal Abilities, Urban Legends, UFOs, Ancient Civilizations, Alternate Worlds. In this world exists every conceivable mystery.” – Count Saint Germaine, DAN DA DAN Chapter 122.

In The Definitive Guide to Japanese Yokai, folklorist and manga artist Shigeru Mizuki muses on exactly what can be defined as a yokai. He concludes that yokai is a broad term that can encompass all the world's mysteries. He encountered yokai on the far islands of Papua New Guinea while fighting during WWII. In such a world, even an obscure cryptid from a small town in Massachusetts can be considered a yokai.

There are different kinds of yokai. Densetsu are legendary creatures, found in ancient tomes where they battle mighty heroes. Minwa are folktales, whispered around campfires and candles in a time when the dark truly ruled the night. Emakimono are yokai created by artists as visual puns and jokes or just cool creatures that might catch a customer's eye. Sekenbanashi are urban legends, spread in modern times by a friend of a friend who heard of a story where… And UMA, known in English as cryptids, are undiscovered animals that just might be real, but probably aren't.

DAN DA DAN has largely focused on the last two categories. Tatsu Yukinobi brought to life obscure sekenbanashi like Turbo Granny and Acrobatic Silky that were whispered about on the internet. And of course, with Nessie playing a major role, Tatsu clearly always loved a good UMA/cryptid. DAN DA DAN> has never been overly concerned with presenting these monsters authentically. Aside from the name, Tatsu creates essentially new yokai with unique purposes, backgrounds, and abilities, often giving them a somewhat extreme interest in male genitalia. As the story progresses, Tatsu goes even further, merging traits and character designs of several yokai into a single creature, which makes up the special magic that is DAN DA DAN.

Let's take another look at some of the yokai of DAN DA DAN!

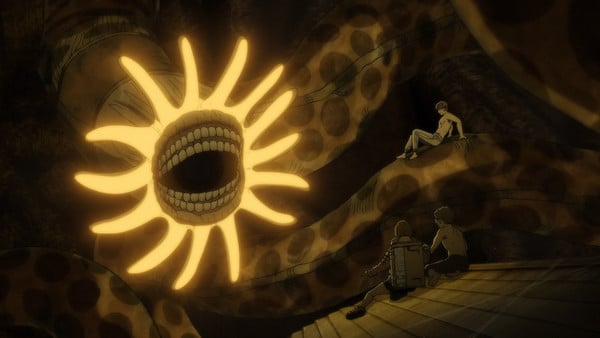

Mongolian Death Worm / Tsuchinoko – This big boy is two cryptids mixed with one Lovecraftian horror to combine into a single creature.

First off are tsuchinoko. These are a well-known cryptid in Japan, with annual hunts every year to prove they exist. They first appeared in the 1980s. Tsuchinoko resemble snakes with wide bodies like barrels. They are said to move by rolling down hills. The Tsuchinoko Shrine of DAN DA DAN is real, located in Hondo, Gifu.

Next are the Mongolian Death Worms. Alleged to exist in the Gobi Desert, they were first noted in 1922, when Mongolian Prime Minister Damdinbazar said, “It is shaped like a sausage about two feet long, has no head nor leg and it is so poisonous that merely to touch it means instant death. It lives in the most desolate parts of the Gobi Desert." No evidence has been found of this elusive creature. It is most likely a misidentified Tartar sand boa, which are equally deadly.

Neither tsuchinoko nor Mongolian Death Worms are kaiju-sized. That comes from dhole, massive, burrowing worm-like creatures created by H.P. Lovecraft. First appearing in his story "Through the Gates of the Silver Key" (1934), they rear up to be several hundred feet tall and are covered in goo. They have been the influence for several giant worm monsters, such as in the film series Tremors.

Hitobashira – Japan was never big on human sacrifices, unless they were. To secure the safety of massive structures such as bridges and castles, a human being was sometimes sealed up within a pillar. There they would die, and by doing so offer protection. However, contrary to the Kito Family, human sacrifices were never made to Shinto or guardian deities. In fact, death is a taboo at Shinto shrines and so offends the kami that those with a death in their families are not supposed to visit until a prescribed period has passed.

Evil Eye – Jiji Enjoji's alter ego is an original Tatsu creation, taking bits and pieces of other yokai such as zashiki warashi and itsuki. The concept of the evil eye comes from European folklore. It was thought some had the power to curse with a glance. The appearance of DAN DA DAN's Evil Eye is a mix of influences, with the twisted face when it first appears likely an homage to Shigeru Mizuki.

Zashiki warashi are the spirits of children. Said to bring good fortune when pleased and bad fortune when annoyed. One way to ensure their blessing is to play with them. While often thought of as house spirits, some speculate they were the ghosts of children who had been killed and buried under the floorboards of the house. However, instead of sacrifices for prosperity, they were culled by heartbroken mothers who could not afford to feed their entire family. Burying their bodies under the floorboards let them feel they were still a part of the home. Zashiki warashi are generally positive yokai and are high on the list of ones people would want in their own houses. No matter their origin, they generally don't bring any harm. For that, you need itsuki.

Itsuki are the ghosts of those who died by suicide—usually hanging—and their malevolent spirits want others to join them. It is said that the only way for them to escape hell is for someone else to die in the same manner and take their place. Those encountering an itsuki feel an overwhelming urge to kill themselves. If not stopped, they will succeed. Itsuki are among the most terrifying of Japanese yokai.

Dover Demon – In DAN DA DAN, this stout little slugger goes by many names. Mr. Mantis Shrimp. The Dover Demon. Kappa. And his real name, Peeny Weeny. Able to transform his body, he takes on traits and powers of many creatures, such as the mantis shrimp's ability to deliver knockout punches underwater. Visually, he draws inspiration from Ultraman aliens like Gan Q and Baltan. What he resembles the least is his namesake, the Dover Demon.

The Dover Demon appeared only a few times in 1977 in Dover, Massachusetts. It was described as "about 4 feet tall with glowing orange eyes and no nose or mouth in a watermelon-shaped head.” It was seen independently by three teenagers who drew sketches of it and swore their testimony was true. Investigations uncovered nothing, and the sightings were soon dismissed as hoaxes or misidentifications of actual animals. But we know the truth, don't we?

The first yokai of onbusman is the curse known as inen. It is found in the village of Saisetan, located on Fukue island in the Goto archipelago of Nagasaki prefecture. They manifest as large lumps on bodies where the restless dead cling to the backs of the living. To dispel inen, a type of shaman called honin can be hired. Honin speak directly to the inen, interpreting their demands and negotiating the price that must be paid. Mizuki Shigeru's painting of an inen looks remarkably like the onbusman of DAN DA DAN.

Inen are spiritually heavy but not physically. For that, you need Konnaki jiji. These yokai appear as babies, but when you get closer you see they have the faces of old men. Their attack is to be picked up, then suddenly increase their weight until they crush their rescuer to death. There are other yokai, such as nure onna, with a similar attack. Although this usually involves handing someone something, like a baby, which then increases in weight with predictable results. Neither Konnaki jiji nor Nure onna can make things lighter. That's entirely Sawaki Rin.

Often called a tsukumogami—meaning an object yokai that comes to life after 99 years—kasaobake are more properly emakimono. Created by artists purely as images for popular entertainment, kasaobake appeared during the late Edo period. They have no stories from traditional folklore and did not appear in any of the major collections. Although there are ancient depictions of creatures with umbrellas for heads, the oldest known image of what we recognize as kasaobake comes from Shichi Henge Sangoru (1815), a print series by Utagawa Toyokuni of Kabuki actor Arashi Sangoro III who incorporated a kasaobake costume in his quick-change routine. Kasaobake were also popular in Meiji-period children's board games.

As for powers, kasaobake have none. They are just what you see. Perhaps the most folklorically accurate depiction of the kasaobake is when Zuma uses it to keep the rain off Momo. They are, after all, umbrellas.

These are only a taste of the yokai of DAN DA DAN. The comic reads on multiple levels, from an action-packed wild ride of wacky adventure to a deep exploration of Japanese religion and folklore blended with world conspiracy theories and whatever else captures Tatsu Yukinobi's twisted imagination. One thing you can be sure of: behind every story of DAN DA DAN, there is another story.

Zack Davisson is an award-winning translator, writer, and lecturer. He is the author of The Ultimate Guide to Japanese Yokai and Kaibyo: The Supernatural Cats of Japan. He translates Shigeru Mizuki's works, including The Definitive Guide to Japanese Yokai and Kitaro, as well as other globally known entertainment properties.

Davisson is on faculty at NYU in the translation and interpretation department, and has lectured on manga, folklore, and translation at institutions such as Duke University, Annapolis Naval Academy, UCLA, The Museum of International Folk Art, Wereldmuseum Rotterdam, and the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Davisson currently lives in Seattle with his wife Miyuki, dog Mochi, cat Shere Khan, and several ghosts.

discuss this in the forum (9 posts) |