Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Panorama of Hell

by Jason Thompson,

Episode XLVII: Panorama of Hell

"These are the vile confessions of an unknown painter who fell to hell because of his obsession with the exquisite beauty and the intoxicating smell of blood."

—Hideshi Hino

If you asked me for the best fighting manga or the best romance manga, I might have to think about it for awhile, but if you asked me about horror, there's no question: Panorama of Hell is the best horror manga there is. It's not an epic like Kazuo Umezu's longer works, it doesn't have a ton of plot or characters, but it's perfect and complete in one volume, 200 pages of living hell.

It's a strange little book, originally published in 1983 in Japan under the name Jigokuhen. It was translated in 1993 by Blast Books, a publisher that specializes in underground fiction and creepy art books: their other publications include titles like Suehiro Maruo's Mr. Arashi's Amazing Freak Show, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch's Venus in Furs (from which the word "masochism" comes) and Dissection: Photographs of a Rite of Passage in American Medicine 1880-1930. Even the translators are creepy: well, maybe not Yoko Umezawa, who I don't know anything about, but certainly co-translator Screaming Mad George (Johji), a Japanese special effects artist who worked on a lot of horror movies. It's been out of print for years, and if you find it, grab it, but be careful. Like the Necronomicon, it's the kind of book where you can almost imagine if you read it, they might find you dead the next day…glazed eyes staring, face covered in blood, your cold corpse lying on the floor of the manga section of Barnes & Noble for the employees to find when they open for the day.

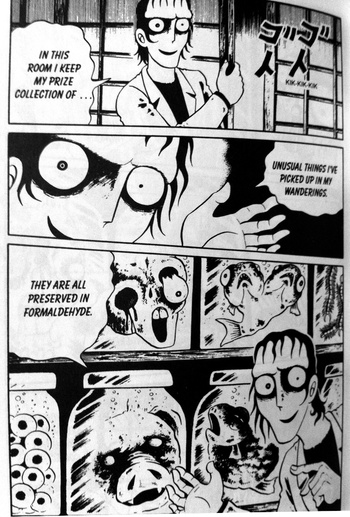

Panorama of Hell is especially disturbing considering Hino doesn't draw realistically at all. Some horror comic artists, like Junji Ito and Jacen Burrows, try to go for an ultra-realistic detailed style, so you can see every spiral-shaped wound, every zombie's mouthful of flesh. But Hino's characters look more like children's cartoons, not inappropriately, since he has spent a lot of his career drawing children's horror comics, with adult works like Panorama scattered throughout. His roly-poly, bug-eyed characters aren't cute in a conventional manga sense—there's no moe, no cute boys or girls, no positive sexuality any kind in Hino's comics—but they're often disturbingly sweet at the same time that they're gruesome. This cute-grotesque style influenced artists such as Junko Mizuno and Kanako Inuki. Hino's simple artwork has oldschool roots, from the time of the '70s and earlier when artists like Osamu Tezuka and Gō Nagai dominated the manga world with their wacky-looking characters. But on those special occasions when Hino wants to show a closeup—for instance, a rotting face covered in maggots—the horrific detail is all the more shocking because it's surrounded by such cartoony art. He draws faces so horrible you can't look at them, textures so revolting you can't touch the page; the only other artist I can think of who can be so simultaneously childish and terrifying is Stephen Gammell, and I dare you to do an imagesearch for his name.

Unlike some of Hino's works, Panorama of Hell is not for children. The title and subject matter summons up a classical theme: Japanese Buddhist Jigoku zoshi ("Hell scrolls") which depict the underworld. With their graphic depictions of sinners being tortured, Jigoku zoshi are a bit like the famous hell paintings of Heironymus Bosch and other Medieval painters, although a religious scholar might point out that in Christianity hell is permanent while in Buddhism hell is just a place you pass through temporarily when you've been too evil in your past life to just be reincarnated as a slug. (Unless you believe Hell Girl.) But in Hino's universe, Hell is much more than a mere bad roll on the roulette wheel of karma. After all, one of the tenets of Buddhism is that existence is suffering; the difference between hell and your ordinary life is just a question of degree. In Panorama of Hell, the narrator's whole life is suffering. Life is hell.

The manga is told in the first person by the narrator, a painter who sits in a studio with boarded-up windows and paints hellish paintings by candlelight. We immediately realize that this is not going to be a conventional horror story about 'normal' people in 'abnormal' situations. The painter talks directly to us, the reader, welcoming us to his world. He takes off his clothes to reveal a body covered with scars from cutting himself and gathering blood to use in his paintings. He has even started drinking hydrochloric acid to vomit up blood clots for more paint. "Oh beautiful, glistening blood…" He needs paint for his masterpiece, his life's work, of which we only see a glimpse at first. "I call it 'The Panorama of Hell.' It depicts the end."

Outside the painter's house is a nightmare landscape of smoke and trash. It's the kind of dark industrial world of factories and smokestacks that we see in the manga of Imiri Sakabashira and Yoshihiro Tatsumi, in the comics of John Bergin and the movies of David Lynch: the gray, dismal world of the modern era. But it's not a deserted wasteland; the neighborhood is busy. A guillotine next to the painter's house is running full steam, chopping deformed heads day and night. Afterwards, the heaps of bodies are cremated, and our hero conspires with the crematorium workers to sneak up to the furnace and get a look at the bodies as they burn. ("It's so exciting! The smell of burning flesh…blistered red skin! Dripping fat! Crumbling bones!")

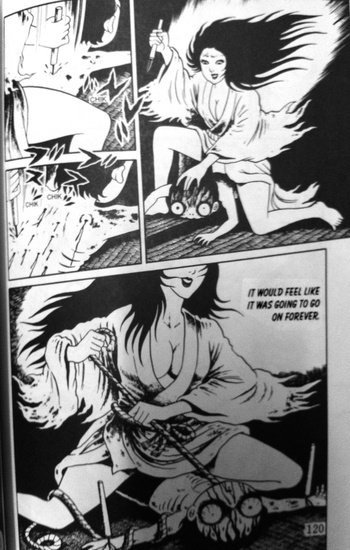

Then we meet the painter's family. His son, Krazy Boy, likes to torture animals. His daughter, Krazy Girl, is an artist like our hero, with similar subject matter. Around the house wanders the hero's senile old mother, who—this is an important detail for the conclusion—can no longer recognize her own children, and instead lavishes her affection on an old rotten pig's head. The hero's wife, a beautiful woman, works at a pub in the town. At night, the headless corpses from the guillotine, those that escaped the crematorium, rise from their grave as zombies and eat in the pub. Since they have no heads to eat with, the hero's wife carves holes in their throats with her knife, and they stuff food down their rotting stumps, including pieces of themselves.

Then we meet the painter's family. His son, Krazy Boy, likes to torture animals. His daughter, Krazy Girl, is an artist like our hero, with similar subject matter. Around the house wanders the hero's senile old mother, who—this is an important detail for the conclusion—can no longer recognize her own children, and instead lavishes her affection on an old rotten pig's head. The hero's wife, a beautiful woman, works at a pub in the town. At night, the headless corpses from the guillotine, those that escaped the crematorium, rise from their grave as zombies and eat in the pub. Since they have no heads to eat with, the hero's wife carves holes in their throats with her knife, and they stuff food down their rotting stumps, including pieces of themselves.

There's a certain Addams Family vibe to all this, but Panorama of Hell isn't just a horror comedy. After the initial splatter, and some beautifully surreal imagery—red fruits sprouting from the blood splattered on the railway tracks by the execution yard—the painter begins to tell us the story of his life. In the process, the manga slowly becomes more realistic, and before we know it, we're not in the over-the-top nightmare world of the beginning: we're dangerously close to the real world.

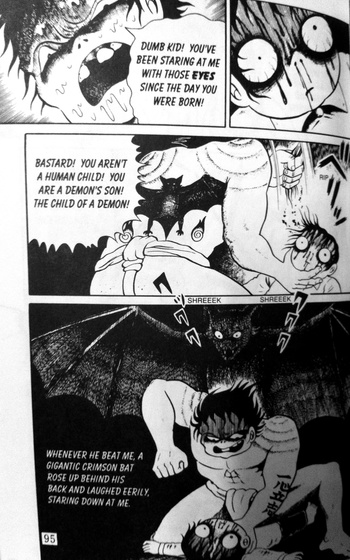

Our protagonist the hell painter, it turns out, is the result of several generations of abuse. His grandfather, father and younger brother are all violent, abusive alcoholics; they are each introduced in the same shot of a hulking man crouched over a bottle of saké, distinguished only by their tattoos. His grandfather, a roving yakuza gambler with a snake tattoo, died a violent death. His father, a pig farmer with a bat tattoo, worked in a slaughterhouse, drank himself into a stupor every night. Like his father before him, he beats his son and wife mercilessly. Blast Books' savage English rewrite makes this abuse sound brutally realistic. ("Bitch, how many fucking times do I have to tell you to stay in the house?") His mother, when she was a young woman, returned the favor by torturing her son. His younger brother, the only person who showed some compassion for the protagonist, escaped his wretched home life by becoming a delinquent, and wound up a "fight freak," provoking bloody fistfights in the streets.

Here is the thing: some of this is real. Hino used the "crazy artist who paints with his own blood" thing in several other manga (Lullabies from Hell, The Collection, etc.)—in Lullabies from Hell the narrator actually straight-up says "I am Hideshi Hino"—but Panorama of Hell goes a little farther into personal territory. In a long interview in the print edition of the magazine The Comics Journal a few years back, Hino talked about the origin of Panorama of Hell. It was written when Hino was in a deep depression, and it is loosely based on Hino's own life. Hino's own grandfather had tattoos and mob ties. And Hino, like the hell painter, was born in the shadow of one of Japanese history's most horrible events.

The hell painter's father, like Hino's father, emigrated overseas when he was young, in a vain attempt to live a better life than his father did. He moved to Manchuria (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manchukuo), which at the time was occupied by Japan. There, in a puppet state supported by the Japanese military, nearly a million Japanese settlers lived alongside a Chinese underclass. When the end of World War II put an end to Japan's colonial ambitions, the tables were turned, and the Japanese settlers in Manchuria and Korea were forced to flee to the mainland, an event depicted in a somewhat bowdlerized way in the 1993 anime Rail of the Star. The shame of Japan's World War II atrocities, the pain of Japan's defeat, the "lost empire" of Manchukuo, all is part of the tragedy of the painter. The painter's father is drafted and forced to kill complete strangers at war, then goes home and abuses his wife and child. But the portrait of hell is still not complete.

"On August 6, 1945, a gigantic emperor from hell appeared in the sky over Hiroshima…with a flash and a tremendous roar, it sucked up the blood of hundreds of thousands." Born on April 19, 1946, a little more than eight months after the event, Hideshi Hino was too young to remember the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, but the roar of the bomb echoes through his childhood. In the manga, the light flash from the nuclear blast travels all the way to Manchuria and strikes the painter's mother, and in that instant, the hell painter is conceived in his mother's womb. Evil omens surround his birth: he is born laughing, with bloodstained hands, and on the long road home from Manchuria, where the Japanese are dying like flies from starvation, the baby crawls over to a corpse and licks its blood. The old midwife is horrified. "All I see is a vast, terrifying hell in this child's future! You mustn't let it live! No one would blame you if you kill it now!" His parents cannot bring themselves to kill the child, although they never love him either. And as the hell painter grows up, we see that he is not merely obsessed with ordinary death and suffering: he is obsessed with the atomic bomb. Perhaps one day he will be reunited with his true father. Perhaps soon.

Panorama of Hell is a fusion of every kind of suffering: personal, political, family. The political elements don't feel tacked on, they feel like a natural part of the story. Almost the only area Hino doesn't directly attack is romantic love, although when we watch the painter's father drag his half-naked wife across the floor by her hair and beat her as the children watch, or when we notice that the painter's wife looks exactly like the painter's mother, we can see the patterns forming there too. And although you don't have to know the story of Hino's life to enjoy the manga, it has a personal rawness, almost like an autobiographical comic. When the narrator talks to us, it feels like his soft voice is whispering in our ear. And in those rare moments when the narrator seems to feel some kindly human emotion, like the moment when he cries at the sadness of his brother's fate, it's a howl from the soul.

One recurring theme inthe manga (as in many horror manga and anime) is that people's bodies change to match their mental state. Human flesh is a plaything of the soul; when someone becomes angry enough, or crazy enough, or sick enough, their form changes and mutates. In one way or another, this happens to several people in Hino's story. It doesn't require explanation, just as Hino doesn't need to explain how historical postwar Japan turned into an industrial hellscape where trainloads of severed heads rush over the landscape day and night. Is it all in the painter's mind? Or is this reality?

But the horror of ordinary life, like the horror of war and abuse and madness, is not the worst horror in Panorama of Hell. I mentioned earlier that in Buddhism, hell and heaven, life and death are all part of a cycle. This is a comforting thought, and one which gives an odd note of optimism to several of Hino's manga. Zoroku's Strange Disease (in the collection Lullabies from Hell), Living Corpse and the untranslated Kaiki! Shinin Shojo are all variations on the same theme: a person decays while they're still alive (or at least undead), their mind trapped in filthy oozing flesh. But at the end of these stories, there is a strange happy ending: when the protagonists finally rot to pieces, their souls rejoin the natural world. They are reborn as the soil for the grass, the dust in the wind, the nutrients in the water. After enduring terrible torments, the dead finally find peace: Nirvana, rejoining a greater consciousness, or rebirth.

But in Panorama of Hell, there is only one way out of our lives: death. The greatest horror is the inevitability of death, the horror of oblivion. "Will it be today, tomorrow, or maybe…the very next second?" the hell painter whispers. The ending of Panorama of Hell feels like Hino would reach out of the manga and grab you and shake you if he could. It comes out of that dark place in the mind where you are feel such fear or despair that you have to tell everyone, to shock them out of their complacency, or just to make them share your pain. What Hino seems to be saying is, in the end, we are all alone, facing oblivion, the final blank page. This is the end. Death is hell.

To celebrate the launch of my new book with Victor Hao, King of RPGs volume 2 on May 24, we're announcing a contest for the greatest King of RPGs fan art! These are the five big prizes:

GRAND PRIZE: A limited edition, full-color King of RPGs t-shirt designed by Victor Hao! Available in M, L and XL. Plus a signed and sketched-in copy of King of RPGs volume 2!

1ST AND 2ND PLACE PRIZES: A signed & sketched-in copy of King of RPGs volume 2!

3RD AND 4TH PLACE PRIZES: A signed King of RPGs minicomic, plus a fully playable copy of "The Siege of Gharazak," the climactic adventure of Theodore Dudek's Neo-Pegana MAGES. & Monsters campaign!

For a chance to win some of this stuff, submit your fan art of the King of RPGs characters to jason (at kingofrpgs.com) by April 15. I'm looking forward to seeing some really weird and beautiful stuff, so please do your best to do some psychic damage on me with your insanely great drawings!

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (15 posts) |