The Mike Toole Show

The Amazing World of Anime Arcade Games

by Mike Toole,

I was back in Japan a couple of weeks back, looking to experience my first Comic Market (it didn't disappoint) and do some other festive nonsense. After ringing in the new year at Kanda Myojin (the official Love Live! shrine, dontcha know), it was time for my wife and I to wander over to Akihabara, to get some souvenir shopping done and meet up with our old pal, games writer and historian Heidi Kemps, who operates the extremely good gaming.moe site. Heidi and her friends dutifully led me straight into Hey, one of the neighborhood's best arcades, in search of limited merchandise and vintage arcade cabinets. Very soon, I was standing in front of a Tokimeki Memorial Puzzle Dama machine. (I'll bet you haven't thought of Tokimemo since… well, since the last time I brought it up.)

The modern Japanese arcade is an interesting piece of work. Very often, these game parlors (which are usually run by Sega, or Taito, or some other entertainment concern like Round 1, who also have arcades in the United States) are multi-story affairs, where the street-level floors house passerby-friendly crane games and print clubs, with the upper floors reserved for actual video games, often broken up by genre. These spaces overwhelm the senses – the cigarette smoke isn't as bad as it used to be unless you're in the corner of the arcade reserved for the mahjong machines, but especially in the rhythm games area, you won't be able to hear yourself think. A couple of years back I noticed that these games started including headphone jacks, and it wasn't until I went to an arcade in Japan that I understood that this is kind of a necessity, because without it, you seriously can't hear a damn thing. As for me, I went straight for the anime video games, which in Hey's case are made up of mostly fighting/beat 'em up tie-ins and an entire Gundam section.

Yep, there it is right there. It's an impressive area, housing damn near the whole spectrum of Gundam arcade cabinets, from the 1993 original to the current-gen Vs. series. As I contemplated the giant Gundam head (cannibalized, I believe, from a Gundam Battle Operating Simulator cabinet – someone correct me if I'm off!) Heidi prompted me to write about classic anime video games. But not about the anime video games you're thinking off – our own retired Todd Ciolek's early X-Button columns often cover a great selection of 80s-era video games based on anime. To understand what I'm gonna be discussing in this column instead, I want you to look at these images.

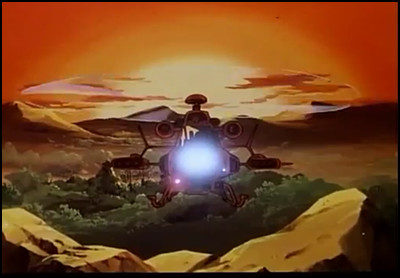

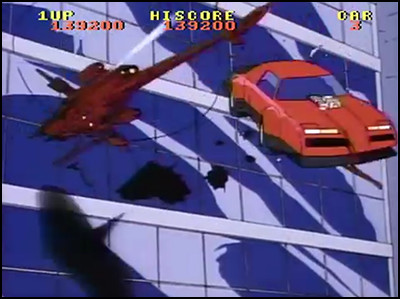

Pretty cool, huh? Looks kinda like a collection of frames from some obscure 80s OVAs. Well, these screenshots are all from arcade games. These below images are also screenshots from arcade games.

Now, wait a minute. That's clearly Harmagedon, and Galaxy Express 999, and Albegas, and The Castle of Cagliostro. These are all animated films (or, in Albegas' case, a TV series), many of them created before the 1980s notion of arcade games had really come into focus. The technology of two companies conspired to make these animated works relevant in arcades well after their original creation: Sega, the video game company, and Pioneer, the LaserDisc people. (Technically, MCA were the LaserDisc people, but Pioneer picked up the slack after the format's slow start in North America and made it a success in Japan.) Sega had this neat idea – they'd use LaserDisc as a storage and delivery method for media used in their arcade games. It wasn't exactly cheaper than using circuit boards (LaserDisc players, particularly durable industrial ones, were expensive then), but it was appealingly modular – in theory, an old LaserDisc game could be swapped out of an arcade cabinet for a new one just by replacing the disc, ROMset, and marquee. Their first game, unveiled in November of 1982 at the Amusement and Music Operators Association (AMOA) conference in Chicago, was called Astron Belt.

Look at that high-tech wonder! Astron Belt was a fairly clunky shooter that incorporated footage from space fantasy movies like Message from Space as a background element. Yep, the presence of finished, high-resolution video was almost completely passive and incidental – but it looked like nothing that had come before it, so for a time, the technology was red hot. But while Astron Belt kickstarted a fascination with LaserDisc technology in the arcades of Japan (it soon got a sequel called Star Blazer, which was retitled Galaxy Ranger in the west, therefore confusing fans of both the Star Blazers and Galaxy Rangers cartoons), the first big hit to use the technology on our shores was basically an interactive cartoon—an interactive cartoon called Dragon's Lair.

You can still play Dragon's Lair on your mobile phone, because it remains a visual wonder. Its animation, directed by Disney alumna Don Bluth, looked so good that it successfully masked what was a fairly terrible game, one that relied on carefully-timed joystick and button moves. Mess up once, even a little? Then you lose a life, in the most jarring and confusing manner possible. People flocked to arcade machines to die as the game's hero, Dirk the Daring, over and over again. I recall playing this game at the age of seven, because it really was that impressive. It also got a lot of attention back over in Japan, where companies like Data East and Taito decided that the thing to do would be to make their own fully-animated games. Instead of Don Bluth, they mostly stuck with a revolving set of players from Toei Animation.

One of Data East's first offerings was Harmagedon (or, if we're being precise, Genma Wars), which used footage from the 1982 anime blockbuster as a framing device for a goofy vertical shooter. The movie was honestly a good candidate for this treatment—from a storytelling perspective it was shambolic, but its intense, vivid action animation (courtesy of wild cards like Yoshinori Kanada and Koji Morimoto) was enormously influential, and would serve as a blueprint for new action animators for the next decade. Reducing it to a fairly simple game suited the material, and soon enough the game was imported to our shores as Bega's Battle. Sadly, most of the rockin' Keith Emerson soundtrack didn't survive the conversion.

Meanwhile, Taito, the Elevator Action people, opted to produce their own original game – one that adroitly reverse-engineered the appeal of Dragon's Lair, with a slightly comical, nearly silent hero navigating a treacherous castle and battling wacky monsters on the way to confront a dragon and rescue the princess. The game, Ninja Hayate, is just as fun to watch as Dragon's Lair, and just about as easy to play. Other notable Laserdisc-driven Dragon's Lair clones would come from Universal Entertainment, the Mr. Do! people—they gave us Super Don Quixote, which is sadly not based on the wacky Don Quixote cartoon from Production Reed. As near as I can tell, the only reason it's called Super Don Quixote is because the hero has to storm a windmill, where he fights and kills Maleficent from Disney's Sleeping Beauty. Because that's why you watch old stuff like this, people!

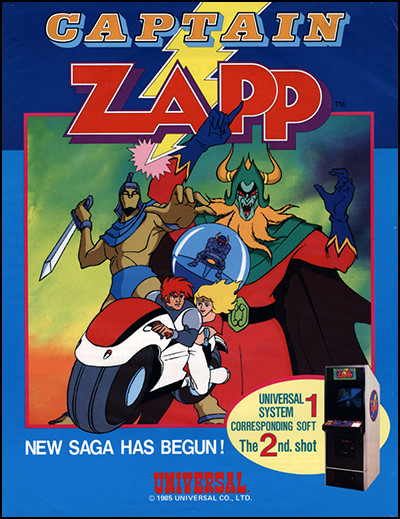

Universal attempted to follow Super Don Quixote with this amazing-looking game with an equally promising title, but it was not to be – Captain Zapp was cancelled. It's interesting to chart the trajectory of these games—most publishers only made a couple, and the public moved on from the format quickly once the gimmick had worn off. Still, a multitude of companies took a chance on LaserDisc games. A partnership of appliance keiretsu Funai and publishing giant Gakken yielded Interstellar Laser Fantasy, a shooter firmly in the same school as Astron Belt, and then swingin' space action game (clearly influenced by Space Ace, Don Bluth's follow-up to Dragon's Lair) Esh's Aurunmilla.

Quite a title, huh? One really notable innovation about Esh is that making the wrong choice wouldn't result in instant death, but simply losing life points and having the game's branching path shifted a bit. Another notable innovation is that the dashing hero character was named Don Davis, so I spent the entire damn game playthrough imagining the composer of the hit Matrix movies playing at being a space hero. Unlike in earlier games, with protagonists that were mostly silent until it was time to scream in terror, Don gets to talk a lot, so that's another change.

At this point, we're into 1984 and 1985, the LaserDisc game boom is hitting its peak, and both Data East and Taito are making some goddamn animation magic for their games. Data East, the Bad Dudes people, struck first with Cobra Command. Originally titled Thunderstorm in Japan (Data East would later make a horizontal shoot 'em up game and dub it Cobra Command, once again confusing western video game dorks), here the player took on the role of a helicopter pilot, ducking and whooshing across cityscapes, caves, forests, and a hidden enemy base to do battle with tanks, jeeps, and other aircraft. The game's story was as threadbare as can be, but it sported pulsing music and first-rate action animation from the gang that had just finished Future War 198X for Toei. It had that awful, unforgiving control scheme, but I still sacrificed a lot of quarters to it, just to savor the animation.

Data East's follow-up to Cobra Command, Road Blaster, was just about as strong (and had its own comedy brand confusion, this time with the Atari game Road Blasters), putting the player in the role of a vengeful sports car driver tear-assing around a city fighting with a mysterious woman and her legions of Fist of the North Star-esque henchmen. I particularly like the faces of the people you almost hit with your car (there's a few of 'em above), rendered in exquisite detail in brief cutscenes between action bits. The game features a lot of good work by Yoshinobu Inano, who supervises the animation and provides character designs – he was the same guy who did character designs for that Starship Troopers anime.

Also in 1984, Konami brewed up their own animation game, Badlands, which opens with the greatest version of the Konami logo ever. The game, run through with horse chases and gunfights, has a light touch – when the heroic cowboy loses out, he gets wheeled off the set covered in bandages and bruises, and the game on the whole is only occasionally incredibly racist. There's even a part where you can lose a life by tripping over a dog. That's the kind of game Badlands is. Konami planned another LaserDisc game, Max-Mile, but it never got finished.

Taito's 1985 Time Gal is the crown jewel of this format. At first glance it appears to be a pretty brazen Dirty Pair ripoff, with main character Reika wearing a similar outfit and piloting similar-looking vehicles. Reika's a 30th-century time detective, traveling back in time to pursue Ruda, a sneering time villain. This game is beautifully animated, and Reika's fully voiced by Yuriko Yamamoto, who chirps and hollers her way through a boisterous performance. The game starts with a pitched escape from Godzilla, and it just gets sillier and sillier – one of Reika's “death” animations involves her losing her pants. Overall, Time Gal is brisk, funny, and always interesting to watch—it's a screamingly obvious pastiche of SF anime of its time, but it still feels like the most complete of the anime-styled LaserDisc games. It was so popular on its release that, for a little while, Reika became Taito's official mascot.

All of these LaserDisc arcade games are extremely fun to watch in spite of the repetition; they feel like lost OVAs. Since the terrain and scenery almost always continuously moving, the animation absolutely has to look good. Usually, it does. Characters and vehicles look nice and consistent, and there's plenty of action to keep things going, Most of these top out at about 12 or 15 minutes long. In my opinion, all anime fans, especially the subset of animation lovers who go moony-eyed over shiny 80s action anime, need to see these games. Now there's no need to play them, which is good, because as games, they're uniformly clunky and terrible. As works of animation? Pretty good, actually!

And how about the other games based on anime, besides Bega's Battle? In a now-familiar twist, Albegas never got finished. That's a real shame, because the existing demo footage seems to hint at an awful lot of new animated material being created just for the game. Cliff Hanger, the Castle of Cagliostro game, was actually a western product, an attempt by Stern Electronics, the Berzerk people, to inexpertly stitch together the Mystery of Mamo and Castle of Cagliostro Lupin the 3rd films into a single game. Slapdash and poorly-dubbed by a single actor, the game nevertheless generated enough interest that it became a perennial “who remembers this?” game, one that I still occasionally stumble across in boutique arcades. And what about that Galaxy Express 999 game?

That makes for a peculiar footnote. Years after interest had died off, in 1987, a tiny company called Millennium Games touted their new state-of-the-art game, Freedom Fighter. The PR material boldly proclaimed it was based on “the popular movie, Galaxy Express,” and while there have been occasional photos of cabinets and video of game footage, this game landed so long after the LaserDisc boom had subsided that it was never easy to find, even as a prototype.

Viewed now, these games and the technology that drove them comes off as a little hokey, but when they came out, there was a feeling that maybe this really was the future of videogaming, that the way to go was to work towards something truly cinematic and immersive. Decades later, I'd say we made it—we just did it with thousands and thousands of polygons used to create a thrillingly true-to-screen Naruto Uzumaki, rather than hundreds of 2D animation frames.

Even so, these old animated games have one extremely obvious spiritual descendant: pachinko machines. Every year, dozens and dozens of pachinko and pachislot machines come out as anime tie-ins, often featuring all-new original animation to entice players to roll up and start gambling. It's a direct line of succession, too – Universal Electronics now mostly makes pachislot rigs, many of them featuring all-new animation of fare like Madoka Magica, Devilman, and Basilisk. These pachinko tie-ins are part of a virtuous cycle, pushing money back into the anime business, and it all sprang forth from a brief phenomenon that, nevertheless, drove both the video game and anime industries forward, balanced on the edge of a LaserDisc.

discuss this in the forum (27 posts) |