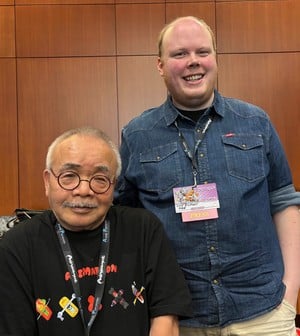

There From the Beginning: An Interview with Anime Legend Masao Maruyama at Animazement 2025

by Coop Bicknell,

If you were to compare the anime industry to a historical document, Masao Maruyama has been around since ink was first put to parchment—or, in his case, paint to celluloid. In his over-60-year career, the prolific creative producer had found himself drawn to challenging projects that no one else would dare to touch. In his own words, Takeshi Koike's Redline is a perfect example of one such project. But when asked what his toughest project was, Mr. Maruyama loudly proclaimed, “Zenbu! All!”

Nowadays, he isn't concerned with getting the next MADHOUSE, MAPPA, or M2 off the ground but rather leisurely pursuing his creative passions with the time he has left. At 83 years old, Mr. Maruyama might have a little trouble navigating the halls of the Raleigh Convention Center—the home of North Carolina's Animazement—but you'd never know it after sitting down for a chat with him. With a razor-sharp wit that transcends the language barrier and swagger for days, you'd almost mistake him for an excited twenty-something who is proudly displaying his choice for best girl on his jacket. For him, it's the original anime dream girl, Betty Boop.

As I started talking with Mr. Maruyama, I found myself thinking of my own grandfather—old school to the core, with all the good and bad that comes along with it. Not to mention that he came off as tougher than nails, seemingly unbothered by his long flight or standing in line alongside the fans to score an autograph from his former MADHOUSE cohort, Hiroshi Nagahama. But what struck me the most about Mr. Maruyama is his kindness. He seemingly sensed the spark in my eyes while we spoke, because he wasn't about to let me leave the room without taking a picture. Nor was he going to leave out our interpreter, North American anime community pioneer and Animag alumni Takayuki Karahashi.

Maruyama-san, you've been a part of the industry since the days of [Osamu] Tezuka-sensei's manga-eiga [manga movies]. With that in mind, what are some prevailing trends you've noticed over the years? How has the industry changed, and how hasn't it?

Masao Maruyama: There have been many changes, especially since I was involved from the very beginning, particularly in TV animation with Tetsuwan Atom [Astro Boy]. Back then, the size of the industry was much smaller. There were fewer people in it, and not much of the wider world really gave us credit for our work. Today, things are very different. Japanese animation now appeals to a worldwide audience, and we've seen tremendous changes. I feel that animation was considered something only for children in Japan. However, I also feel that sentiment started to change around the time we made Genma Taisen [Harmageddon]. Anime started appealing to mature audiences around then as well.

You've previously spoken at length about the impact of Ashita no Joe [Tomorrow's Joe] on your career. From how it brought the original MADHOUSE team together to how the departure of [Osamu] Dezaki-san and [Akio] Sugino-san kicked off MADHOUSE's second era with [Yoshiaki] Kawajiri-san. Fifty years on, how do you feel about the series? And what's it like to know that Western audiences are just now able to watch it officially?

MARUYAMA: It all started while we were at Mushi Production [where Ashita no Joe was produced], which went belly up. A lot of the staff were wondering what they'd do next. So, we got together and founded Studio Madhouse. That's where Dezaki, Sugino, and I went after we made Ashita no Joe. However, Dezaki and Sugino went on to found their own studio, Annapuru [where the duo made Ashita no Joe 2]. The next generation of MADHOUSE included Kawajiri, who stayed at the studio, and we made shows such as Marco Polo's Adventures.

Looking back on it, I think Ashita no Joe was probably the start of us courting a more mature audience with our material. It was one of the earliest turning points in Japanese animation, where it started pivoting toward more hardcore and action-oriented stories. I was fortunate to be there at the same time as talents like Dezaki, Sugino, Kawajiri, and also Rintarō, who directed Genma Taisen [Harmageddon], as we gathered at what was our starting point—Ashita no Joe.

When you and your colleagues left Mushi Pro to start MADHOUSE, was there a certain goal you all had in mind? Did you feel like you had something to prove?

MARUYAMA: When we were starting MADHOUSE, there were still major studios around, such as Toei and Nippon Animation. So as a personal endeavor, I was more interested in what I could do on my own—as an individual.

Do you remember why Aim for the Ace! was selected to be MADHOUSE's first project? Was it simply a matter of what was being offered to you at the time, or did your reputation as “the team behind Ashita no Joe” come into play?

MARUYAMA: Aim for the Ace! was a title that Tokyo Movie [TMS Entertainment] was producing back then, and we took them on as a client. That's where Dezaki and Sugino came in.

On the topic of Aim for the Ace!, while attending one of his panels, I asked about how he allegedly used the pen name “Yumeji Asagi” while writing episodes of the original 1973 TV series. He quickly but coyly replied while flashing a knowing smirk.

MARUYAMA: Did I really write anything for that show? [Everyone starts chuckling] I'd say it's not in my memory, but if I did (and I possibly did), it would've been because there wasn't anyone else available at that time. And then the director would've said, “Can you be a pinch hitter for that?” It would've been a moment in production when we were short on time and budget. If there wasn't anyone else willing to do it—and I would have never volunteered for this—but if there's no time or money, and if it's something to appease the director, I'd just do it. A great director could always take a good screenplay and make a good work out of it. A good one would just rewrite a badly written script and do as he pleases. I think I excelled at coming in as a pinch-hitting writer who could deliver something that could be easily rewritten.

I believe I wrote under a pen name the most for Ashita no Joe, using names like “Kobayashi” and others. This is because Director Dezaki, regardless of who the screenwriter was, would've perhaps used three lines at most from the script and come up with the rest himself. So, most writers would just quit the show in anger and protest. Eventually, there would be no one left, and I thought, “Well, if he's just going to use three lines anyway, I could just write up a general guideline, and he would happily rewrite the script, then make a good show out of it.” So that's how I ended up doing a lot of substitute pen name writing.

In a recent interview, you've talked about being the person on a production who'll do anything that needs doing—from cooking to scrubbing toilets and writing a script from time to time. With that in mind, how has your work ethic changed over the years? How does your approach to modern projects differ from how you handled the odds and ends in your early days?

MARUYAMA: I started MADHOUSE, but as it grew and became a bigger studio, it became harder for me to oversee the individual parts of it. I then wanted to go smaller, so I started MAPPA, but it also grew into a larger studio, and I only kept getting older. So, I left the management of the studio to a younger president, and I continued on by establishing a smaller studio. MAPPA has been left to younger producers and management who now oversee the staff. My inclination has been to start up a studio, go to a smaller start-up, and then just age gracefully and fade out over there.

Having been at this for so long, what is your philosophy for keeping your coworkers happy, healthy, and creatively fulfilled? How has that changed over the years?

MARUYAMA: I tend to think that morale is at its best when you can enjoy the work. If you think the pay is too low or the work is arduous, then you're only making it tough for yourself. So, I tend to think that it's most important to love the work.

Since I brought up your reputation for cooking a few minutes ago, I've got to ask: What's the one dish your coworkers are always asking you to make for them? Was there something special that Dezaki-san was particularly fond of?

MARUYAMA: Hmm, maybe curry or gyudon? There's an expression we have in Japan: “Onaji Kama.” It means to eat from the same pot, the same cauldron. It tends to reinforce camaraderie and strengthen bonds among colleagues.

Given your role in fostering the careers of irreplaceable talents like [Satoshi] Kon-san and [Sayo] Yamamoto-san, how do you feel the industry is doing when it comes to talent development these days? Do you believe it's still a key focus for studios, or is it falling by the wayside in a rush to get the next project out?

MARUYAMA: I would say that I never was the one fostering talent, I could only prepare an environment for them. I tend to think that talent is something that fosters itself. So, I'd just prepare a location—an environment in which the self-fostering could take place.

It's been a little over a year and half, but congratulations again on the release of Pluto. Considering that it was your dream project for so long, what did it feel like to finally get it out the door? And to discover it was well-received too?

MARUYAMA: I started at Mushi Production under Osamu Tezuka, and Naoki Urasawa's Pluto is a work that was inspired by Tezuka's characters. I've also been working with Urasawa since we [MADHOUSE] animated his series, Yawara! [in 1989]. It's been the best reward that I've been able to work on Pluto for over a decade. I worked on just Pluto during that entire period. I was worried if I'd actually live to see its completion, but I managed to do it. I'm very grateful for everything, especially the staff who made it possible.

Fantastic, I'm glad you're still around to see it happen.

MARUYAMA: Thank you.

As someone who has maintained a close creative relationship with both Tezuka-sensei and [Naoki] Urasawa-sensei, what was it like as a creative producer to best represent both of their sensibilities in a single project? Did you ever find yourself thinking, “I wonder what Tezuka-sensei would say if he was in this meeting?”

MARUYAMA: Well, he may have scolded us and encouraged us to do better. Both Tezuka and Urasawa were never satisfied with what was in front of them. So, I know that he [Tezuka] would've just cracked the whip and kept on telling us to do better.

With Pluto finally completed, what was your biggest takeaway from the whole experience?

MARUYAMA: I felt that Tetsuwan Atom [Astro Boy] is a great starting point, but Urasawa took that and expanded it into a story with much greater context behind it. We can see that because our own world has greatly expanded since the days of Atom, and Urasawa's talent allowed it to grow with the times, so we can appreciate it today. It was wonderful to see that kind of dynamic progress unfold in front of my very eyes.

Speaking of adaptations, Mr. Maruyama had this to say at one of his panels when a fan asked, “Where do you find the balance of staying true to the original work while adapting it for animation?”

MARUYAMA: Whether there would be any change from the source material really depends on the project or the producer. But first of all, I will be the first one to point out that manga has its own narrative grammar, as does a novel, and all these are different from the narrative grammar you'd find in anime. So, you can't use the same storytelling techniques the source material does. If anyone has a deep love for a certain manga and wants to see the exact same thing on-screen, they would be better off by just reading it...then go on a rant about how things have been changed. But there is one exception to that, and it's a recent title of mine called Pluto.

It's a very long story, going on for eight volumes in the manga. If we were to faithfully recreate it in anime, it would take eight hours to do it. I told Urasawa that I wouldn't be capable of making an eight-hour epic at this point. If he wanted it to be faithfully animated, he'd have to just call it quits and not do it or agree to a drastic rearrangement of the story. Urasawa wasn't willing to quit the project, so he said, “Maruyama, please go ahead and do it.” At first, I insisted that maybe half of the story needed to be removed, but that would compromise too much of the narrative—it wouldn't be possible. I told Urasawa, “Your manga is perfect as it is, there would be nothing about an anime that would enhance it.” But then he said, “No, that's not true. A breeze wouldn't flutter when drawn, nor would you actually hear the sound of birds chirping. And, none of the dialogue is actually spoken aloud. Those are some things an anime can deliver.” I told him that some story elements might have to be altered. So, this was the one example where the source material was so perfect that nothing could be changed. That's how Pluto came to be.

There's a different example where the source material was drastically changed for the anime adaptation, and that's a feature called Perfect Blue. The original novel is a story about a boy who chases his ideal idol and becomes a stalker, but I have no interest in that kind of subject. Instead, I went to the creator and said, “That's not the sort of narrative that Satoshi Kon or myself would be capable of working on, but if we change the story's perspective and make it about a girl who gets freaked out by a stalker. Then, eventually, something strange happens, where reality and fantasy become inseparable, and you go into a psychotic paranoia. That would be a psychological thriller that we could totally do.” That is how the film version of Perfect Blue came to be.

© 山中貞雄 / 「鼠小僧次郎吉」製作委員会 |

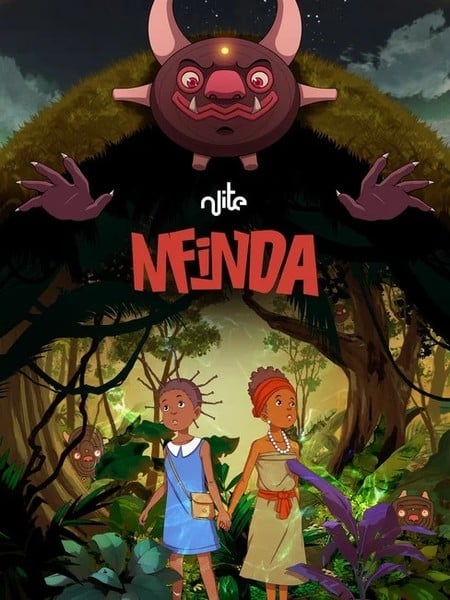

©N LITE |

Looking forward to your next project, N LITE'S MFINDA, what was about the film that initially sparked your curiosity? I'm personally astounded and excited about the incredibly diverse team working with you on this film.

MARUYAMA: I'm getting to be one of the oldest around, so I like to leave the heavy lifting to the younger creative talents and producers. I like to pick up short subjects that others might not be so encouraged to tackle and quietly make those happen. Directed by Rintarō, my latest work [Nezumikozo Jirokichi] is a 30-minute short subject, and it's not based on the story of an animator, but a Japanese live-action director by the name of Sadao Yamanaka, who died in the war at the age of 28. This is based on his screenplay about Nezumi Kozo, the Rat Kid. We made it in monochrome—black-and-white—as a silent film in the old style of Japanese cinema. This is the kind of work that I can do today, because of where I've been and what I like to do.

As someone who was there at the birth of Anime, how does it feel to be in the room for the birth of AFRIME [Afro-Anime] with MFINDA?

MARUYAMA: There isn't much we've specifically announced beyond the title, so I have to refrain from making any specific comments on it.

Finally, aside from your current projects and taking it easy, what's next for you?

MARUYAMA: For right now, it's my aim to pick up projects that others wouldn't be capable of picking up. And they would be the kind of stuff that only old timers like me could do—the sort of projects my limited footsteps would allow.

I know the feeling, my dad is 77.

MARUYAMA: 77?! That's still young! You gotta be 84 or older!

Special Thanks to the Animazement Staff for facilitating this interview and Mr. Karahashi for his linguistic expertise.

discuss this in the forum (2 posts) |