Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Japan Inc.

by Jason Thompson,

Episode XVI: Japan Inc.

"This book tells us…about the national mood in Japan, where apprehension and optimism jostle one another as the country heads towards what some predict will be 'the Japanese century.'"

-Peter Duus, introduction to Japan Inc., 1988

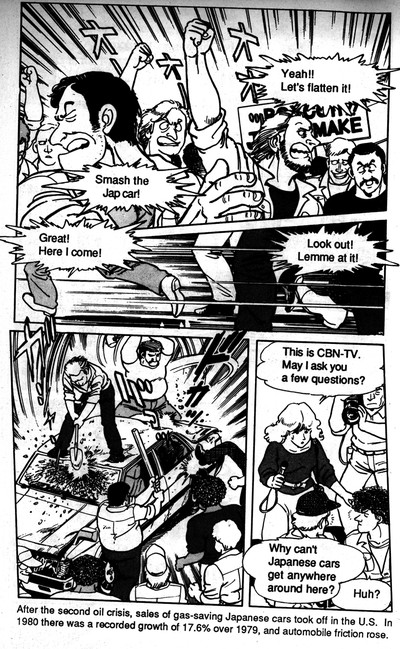

In the 1980s, America was obsessed with-- and frightened of-- Japan. Japan had the second largest economy in the world, and it seemed like the sky was the limit. In industries like electronics and automobiles, Japan was booming and America was falling behind, and unemployed American auto workers and opportunistic politicians fanned the flames of racism and paranoia. In 1985, on the 40th anniversary of the end of World War II, Senator Howard Baker, who served in the U.S. Navy during the war, told his colleagues "First, we're still at war with Japan. Second, we're losing." Cold, calculating Japanese businessmen were villains in movies like Robocop 3 and Rising Sun, and in Blade Runner (which in turn was a huge influence on '80s science fiction manga and anime), the future looked distinctly Japanese. In 1982, Vincent Chen, a Chinese American living in Detroit, was beaten to death on the night of his bachelor party by two autoworkers who mistook him for one of the Japanese people they blamed for taking their jobs.

Of course, at the same time some Americans were committing hate crimes, other Americans were getting into sushi and ninja. But although Westerners have always been interested in Japanese culture, the Japanese economic boom of the 1980s also brought about a new kind of weeaboo: economists and businessmen who were fascinated with the Japanese "economic miracle." After all, they had recovered so well from the destruction of World War II, surely they must be doing something right. Maybe it was tea ceremony. Or maybe manga. And so came about the very small, specialized industry of manga translated for American businessmen wanting to learn about the Japanese economy and culture. Mangajin magazine, which taught people how to read Japanese by including little bilingual segments of seinen and josei manga, ran from 1990 to 1996 and printed some very interesting excerpts of manga, including a whole anthology book, Bringing Home the Sushi, which is worth checking out.

Also worth checking out is Japan Inc.: An Introduction to Japanese Economics (The Comic Book). This strange little manga on the Japanese economy was translated in 1988 by the University of California Press, making it more of an academic book than like something you'd find in Borders. (Oddly, the second volume wasn't published until 1996, when the Japanese economy was beginning to wind down.) Drawn by veteran mangaka Shōtarō Ishinomori, Japan Inc. is half academic paper and half business-world drama. Like the super-long-running manga Section Chief Kosaku Shima, it's a manga about how to be a good salaryman (I say "man" instead of "person" because female business executives are out of the picture in this manga). Unlike Shima, which runs thousands and thousands of pages, it tries to cram all the crises of the 1980s into 314 unbelievably dense pages. It's no surprise to find out that the book is a manga adaptation of a Japanese economics textbook -- although the all-text pages every 20 manga pages or so, explaining various economic factoids, might clue you in if the story doesn't.

Japan Inc. opens in 1980 with Detroit auto workers smashing Japanese cars in protest over competition from Japanese automobiles. "Chrysky Motors" and "Toyosan Autos" are at war over the automobile market, and Toyosan is faced with a tough choice. Should they try to buy factories in the U.S., making their cars in America, to ease over tensions and circumvent American anti-import laws? Or should they keep making their cars in Japan, so the Japanese subcontractors and laborers don't get screwed over? (If this doesn't sound very exciting, maybe I should mention that a corrupt union organizer is blackmailed with photos of himself seeing a dominatrix, so that he won't oppose moving Japanese jobs overseas.)

Quick! If you were in charge of a corporation, what would you do? That answer is left to the story's protagonists, employees of the Mitsutomo Company, the sort of giant corporation which in another genre would probably be producing a deadly zombie virus or rogue artificial intelligences. Here, though, the corporation is no more evil than the people who work for it, that is to say part good and part evil. The heroes are two thirtysomething middle-management businessmen, idealistic Kudo (or "kind-hearted Kudo," as the character introductions describe him) and "wily Tsugawa." Kudo is all hero: he has the thick eyebrows of earnestness, the spiky hair of enthusiasm, and a face which is either serious and thoughtful or goofy and happy. Tsugawa has a widow's peak and is always scowling wearily or smiling a sinister smile. They work with Amamiya, an office lady whose role is mostly to support Kudo and make cute faces. In story after story, Tsugawa and Kudo play the same roles: Tsugawa wants to do whatever will make the most short-term profit at the expense of people, and Kudo wants to protect the subcontractors, the employers, the little folks, the human factor. They argue ceaselessly. ("What are you, the company humanitarian? Sometimes you have to kill the small to give birth to the great!" "That's stupid! You're only looking at the giant trees above ground. Think of the roots underground that support them!" "Get rid of you no-good sentimental idealism!") The other characters include several old wise businessmen, and Ueda, the inexperienced young office assistant who borrows money from Amamiya, giving the other characters an excuse to talk about the importance of paying back your loans.

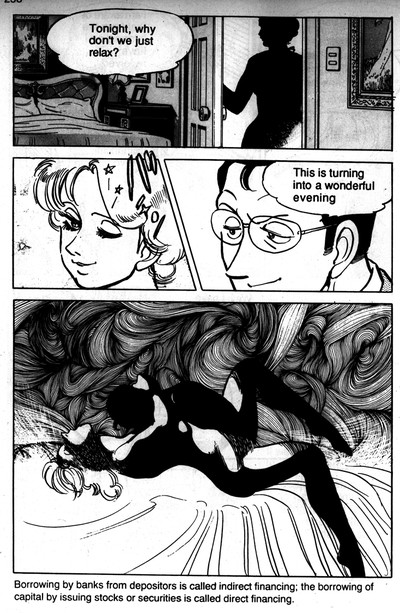

Japan Inc. is divided into six chapters, each one telling a mini-story about a different aspect of the economy or of Japanese history. The rising yen is hurting Japanese exports. The company sends envoys to "Middle Eastern Country P" to build an oil refinery, but there's a revolution and everything falls apart. The company considers investing in old folks' homes to deal with Japan's aging population (incidentally, the graying of Japan is one of the few economic and social predictions Japan Inc. gets absolutely right), but after seeing the dismal conditions in a facility, they decide to focus on home care and better outpatient medicine instead. The reminisces of the older salarymen summon up flashbacks to the '60s, the '70s, and at one point as far back as February 26, 1936, in which rage against the federal government's monetary policy prompted an attempted coup by army officers and the assassination of the finance minister. In between quotes by economists like Milton Friedman and Adam Smith, Ishinomori throws a bit of mild fanservice -- nothing as explicit as the sex in Section Chief Kosaku Shima (who celebrated his "sexy sixtieth birthday" a few years ago, speaking of the graying of Japan), but we see drunken Japanese businessmen watching cowboy-themed strippers in Ginza bars. As for violence and mayhem, in addition to autoworker riots and Islamist revolutions, one story sees the Vatican involved in a financial scandal ("If one of its banks collapses, it will lose confidence of Christians all over the world!"). Shadowy figures make backroom deals ("We can always lie. That's politics"), and in one subplot, dropped as quickly as it's introduced, the mysterious manipulators plot to replace the dollar and the yen with a new joint U.S.-Japanese currency, the "dolen." Ex-president Ronald Reagan shows up in one chapter ("My greatest concern is jobs! If the unemployment rate goes down, we can win the next election easily!").You almost expect Golgo 13 to show up and start assassinating people.

As a comic, however, Japan Inc. has some serious problems. Several factors make it hard to read, one being the weird formatting choice in the English edition: the pages read left to right but the panels aren't flipped, so that dialogue has to be rearranged and partially retranslated to make sense read in the opposite order from the original. The fact that it doubles as an economic textbook and a comic doesn't help either; there are lots of sidebars of economic information with only flimsy connections to the story, almost like a form of metadata. ("The American economist Raymond Vernon's 'product cycle theory' argues that the development of industry and its relation to trade are divided into three stages. Japan has already entered the third stage." Huh?) All this extra information makes the already dense story even denser, and the story jumps from scene to scene so quickly it reads as if it were abridged. But no, it really is that confusing. Each chapter opens with a one-page summary of the characters and plot, which often explains the story better than the manga itself does.

The truth is, Japan Inc. isn't so much a story as a propaganda piece about the power of the free market -- the power of 'good capitalism,' in the person of Kudo, vs. 'bad capitalism,' in the person of Tsugawa. Some scenes are as cheesy as something out of a 1950s educational film: in one, Kudo picks up a pencil and goes on a long speech to his coworkers about the 'god of economics.' "It was people who made this pencil, but it was something like a god of economics who guaranteed it…To make pencils, we use the absolutely straight cedars of northern California or Oregon. We need many tools—chainsaws and ropes and trucks to bring the felled trees to the railroad siding…to make the saws and the engines, we must mine for minerals and make crude steel…" But other bits are simpler and, clichéd or not, more satisfying. Kudo always thinks of the workers, and distrusts the stock market and other abstract economic games with no human element. ("I think we must have money for our real purpose -- to make and sell good products -- but it's stupid to run a business to raise profits simply by moving money around.") Perfect Kudo manages to balance his work and home life (albeit mostly offscreen), while Tsugawa, like some Mad Men character, barely has time to glance at his sleeping children and argue with his alcoholic wife before heading back to work. ("All you think about is business! You used to be different!" "Shut up! I put you completely in charge of the house! I'd like to do more with the kids, but I've got work to do! It's the wife's job to be a pipeline between her husband and her children!") A late-night conversation between Kudo and Tsugawa brings their story arc to a conclusion and explains the difference between them as well as anyone could. "Has it taken the two of us to make one complete person?" they think.

Times have changed since Japan Inc. In the mid-1990s Japan's economy collapsed, leading to what is called the "lost decade," a recession so long and deep that Barack Obama mentioned it in a 2009 speech warning about what might happen if the federal government didn't intervene in the US economy. The rise of Japanese pop culture exports -- video games, anime, manga -- was one of the little bright spots in Japan's economic collapse, but it hasn't been enough to turn around the bigger picture. Former Prime Minister and famous fanboy Taro "Rozen" Aso openly promoted the idea that anime, manga and galge might revitalize the economy the way televisions and automobiles had once done. "By linking the popularity of Japan's 'soft power' to business, I want to create a 20-30 trillion yen ($200-300 billion) market by 2020 and create 500,000 new jobs," Aso said in 2009. Unfortunately, the plan failed, and record unemployment forced Aso to resign as Prime Minister in August 2009. (Gottsuiiyan, a manga translator and blogger (http://www.gottsu-iiyan.ca/), mercilessly mocked Aso's initiatives. "In terms of international relations and global economic clout, soft power via comics, cartoons and teenage cosplayers is the diplomatic equivalent of erectile dysfunction. “Soft" it surely is, but the hard truth is that it isn't very powerful.") In any case, Americans soon forgot about the terrifying Japanese threat to the American Way of life, etc., and found other foreigners to be scared of. But I wonder if any American salarymen who started reading business manga 20 years ago, to discover secret Asian sales techniques and business etiquette and all that stuff, are still reading manga for pleasure today?

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (9 posts) |