Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Walking Man

by Jason Thompson,

Episode LXXXIX: The Walking Man

"What was it that made it so peaceful? Time goes by very slowly, like the river…a brief interlude in daily life, where nothing is pressing."

Since it's the holidays and everyone is taking it easy (at least I am, and I hope you're able to), it seems like a good time to talk about a manga in which nothing happens. The Walking Man, by Jiro Taniguchi, is less a story manga than a form of virtual reality. It's like a diary in manga form; it's like a sandbox video game where you lose track of the plot and just end up looking at the scenery, and that's fine. Really, though, it's not "like" anything except wandering around in the world, lying in the grass, climbing a tree or walking down an undiscovered street. "If you like to go on walks, this is the manga for you" doesn't make for great back-cover copy, but it's a pretty accurate description, only it doesn't capture why it's one of my favorites.

Jiro Taniguchi draws a bit like Katsuhiro Ōtomo (Akira), but whereas Otomo used his ultra-realistic style to draw near-future urban science fiction stories, Taniguchi is more inspired by reality. When he does go on flights of fancy, it's not into the future but into the past, in nostalgic stories set in Meiji- and Showa-era Japan (A Distant Neighborhood, A Lion in Winter, The Times of Botchan) or inspired by the hard-boiled detective noir genre (Hotel Harbor View, Benkei in New York). Taniguchi is incredible at settings: his backgrounds are never just backgrounds, like the premade flat photo-backgrounds in a ComiPo! comic, they're places. Usually, like most artists, he uses the places as the setting for a story, but in The Walking Man, perhaps the purest expression of his style, the places are the story. There's no melodrama here, no plot twists. Reading The Walking Man reminds me of walking around San Francisco, always wondering what's at the end of that street, what's over that hill, who lives in the house with the walled garden over there.

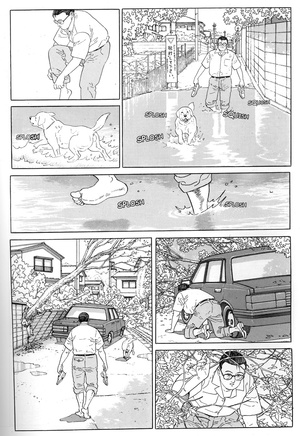

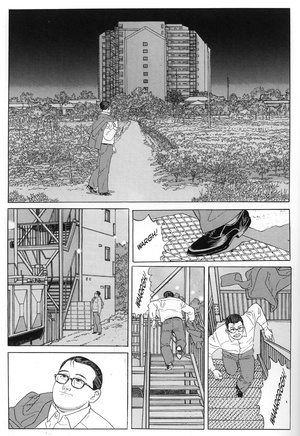

The main character, essentially a stand-in for the reader, is a salaryman who lives with his wife. We never find our their names, occupations, or ages, and it isn't important. When the book begins, they have just moved into a new house in a new neighborhood, and the man is getting to know the place. In short chapters of about 8 pages each, he wanders here and there, usually alone, sometimes with his wife. (They seem to have a good relationship.) While he's riding the bus, he spots a hill in the distance down a side street, so he gets off the bus and goes on a detour to climb it. We see the world as he sees it, stopping to glance at the details: an unusual design on a manhole, a strange bird taking flight, a vase of flowers at the site of a traffic accident by the roadside. There is almost no dialogue. Very rarely, he meets people on his walks: a birdwatcher, a fisherman, an old lady. Occasionally, he has little challenges, or he gets just a little naughty on his explorations: he sneaks around people's backyards while a woman looks at him suspiciously from an upstairs balcony, he runs up ten flights of steps to a rooftop just to see the sun rise, and he can't resist sneaking over the chain link fence to swim in the neighborhood swimming pool at night after it's closed. In another chapter, he builds a replacement for a fallen birdhouse, and in another chapter, they adopt a stray dog.

The unnamed town is a suburban in-between place with no big landmarks but lots of little ones, the kind of place that might have been an empty field fifty years ago, and where there's still a bit of nature in every grassy patch and creek and tree. Most manga seem to just take places in genero-Tokyo if they take place in the real world at all (maybe their editors actually prefer them to use generic settings, the generic riverbank, the generic school, the generic beach resort etc., so no readers will get confused or alienated by local details), but The Walking Man seems to take place in the kind of neighborhood where Japanese manga readers might actually live. Entire chapters are built out of little changes to the environment: in one chapter, a storm comes through and transforms the neighborhood, leaving behind puddles of water, streams in the gutters, fallen branches and leaves. In another chapter, the main character walks at night, observing how the darkness and streetlights change everything. In still another chapter, he accidentally breaks his glasses, so he sees everything as a blur, until he puts on the broken glasses and sees dozens of reflections in the cracked lens. Each chapter is a virtuoso display of drawing, with Taniguchi challenging himself to capture new aspects of the real world with pen lines in black and white.

Taniguchi's finely detailed art is influenced by European comics, and European artists like him too. He worked with famous French artist Moebius on the disappointing sci-fi collaboration Icaro, but a more significant fan was Frédéric Boilet, a French artist who moved to Japan and collaborated with Taniguchi (sort of—Taniguchi only did the screentones) and Benoit Peeters on the graphic novel Tokyo is My Garden. In his 2006 manifesto on manga, Boilet wrote that, basically, the best thing about European comics were the realistic art, and the best thing about manga was the realistic storylines. ("Unlike Franco-Belgian bandes dessinées, which until the '90s were quite content to rehash the same sci-fi, historical or adventure universes, manga has always emphasized daily life as a theme.…This attachment to daily life is for me the principal reason of manga's success with a broad range of readers…") To Boilet, a mangaka like Taniguchi represented the best of both worlds, a fusion style of realistic art and mellow, daily-life storylines, which Boilet called "Nouvelle Manga." Although Boilet was obviously not reading too much shonen and shojo when he developed his idea that manga is "attached to daily life" (Boilet's own works are obviously influenced mostly by seinen manga, particularly his unfortunate fetishization of Japanese girls), I know what he means; although I love a good sci-fi or fantasy story, one of the things that really got me into manga as opposed to American comics was the relative realism of relationship-focused, everyday stories like Maison Ikkoku. Taniguchi shares some of the same European influences as Katsuhiro Ōtomo, but unlike Otomo, Taniguchi doesn't make the scale of his stories bigger and bigger, showing more and more exploding skyscrapers until the reader gets crushed by the weight of the drama and the screentone. Instead, Taniguchi focuses inward, as if using a magnifying glass. He makes his manga out of delicate observation of the world around him, the same way The Walking Man finds a shell in his backyard and examines it closely, or the birdwatcher in chapter 1 watches the birds.

The Walking Man was translated by Fanfare / Ponent Mon and released as a nice coffee-table edition; I said that it's like virtual reality, but maybe it'd be simpler to say it's like a book of Japanese landscape drawings. But although it doesn't have a plot, it does have some emotions, mostly a feeling of fascination with this world we live in, and the warm peaceful feeling that, at the end of your long walks, someone is waiting for you at home. In one scene towards the end our hero runs into an old fisherman fishing in a shallow stream. "If possible, I hope none will bite," the old man says. "It's better if I don't catch anything. I rushed around enough in my life…so that now it's time to take life easily, slowly…it's wonderful, isn't it?" Those special moments of finding something on the beach, of watching the sunset, of enjoying a cup of tea with your loved one on a hot afternoon: these mixed feelings of wondrous expectation and soothing calm are what The Walking Man is all about, and sometimes, when I'm not up for my usual manga diet of hyper melodrama, it hits the spot. Fans of similarly mellow, wonder-filled manga like Yotsuba&!, Aria, Aqua and Yokohama Kaidashi Kikô might like it, if you can overlook the fact that the main character is a stocky middle-aged guy with glassesinstead of a kyara moe girl. (And also, he gets naked on three pages when he goes skinny-dipping—but don't worry, there's zero sexuality in this manga. I'd loan it to a 10-year-old.) I've rarely felt that a book more closely captured a sense of place and a feeling, and even when it's winter and it's rainy and gray or snowing outside, The Walking Man on my bookshelf feels like a little bit of warmth and calm in the storm.

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (9 posts) |