Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Junko Mizuno

by Jason Thompson,

Episode CXXV: Pure Trance & Junko Mizuno

"Some people want to think that I'm mentally ill. I'm just making things that I enjoy."

—Junko Mizuno

Junko Mizuno's art used to scare me. Beneath her curvy, Pop Art drawings of little girls is a sense of power and danger. Her women, their legs often spread wider than their eyes, look like idols of some sinister religion; shrines to My Little Pony, Sanrio, Strawberry Shortcake, Polly Pocket, lined with flames and blood-dripping hearts and leering skulls. If anyone ever tried to tell Mizuno how "shojo manga" was supposed to be drawn, she obviously ignored their advice, and it's a good thing.

Manga is only a small portion of her output; she designs T-shirts and toys, draws gallery paintings and rock posters. When Jeremy Riad interviewed her a few years ago, after Mizuno had moved from Japan to her current home in San Francisco, they bonded while sorting through boxes of her toys. (Mizuno: "Do they still make Easy Bake Ovens?") She loves '70s and '80s "cute culture", both American and Japanese, but she also loves exploitation, gore, sexuality; her cutesy-creepy kawaii-guro character designs may be inspired by Hideshi Hino. Her sense of design, her ornately patterned backgrounds, and some of her pervasive sexual imagery may come from another one of her favorite artists, the Victorian decadent illustrator Aubrey Beardsley. Her love of dominant women with their bodies on display has echoes of Eric Stanton, a 20th century fetish artist who drew wild women in lingerie, tormenting men and each other. Like Wonder Woman, created as a feminist superhero but armed with a magic lasso she uses to rassle men into submission, it's art on a murky borderland between female empowerment and female exploitation. Mizuno's art is like a trawler ship searching these deep cultural currents of porn.

Junko Mizuno's work first came to America mostly thanks to Izumi Evers, a Viz designer who was a fan. Her first works published in English were original drawings commissioned for Viz's PULP magazine, illustrating a series of translated essays on Japanese prostitution (technically, working in a Soapland): lots of drawings of soap and bubbles and happy-looking little men like babies in the hands of naked women. Viz also translated one of Mizuno's science fiction stories, "The Life of Momongo," in their underground comics anthology Secret Comics Japan. But it was Last Gasp, an underground publisher, who translated Mizuno's first really long-form work, Pure Trance.

Pure Trance, Mizuno's first manga, was created when she was in her early 20s. Drawn in CD booklets for a set of techno CDs (which is why the comic pages are square), in 1998 it was revised by Mizuno and published as a graphic novel by East Press, publishers of the underground magazine Comic Cue. Like her short story in Secret Comics Japan, the plot is like a 1970s sci-fi apocalypse movie (or maybe Osamu Tezuka's Phoenix) reimagined in a fever dream.

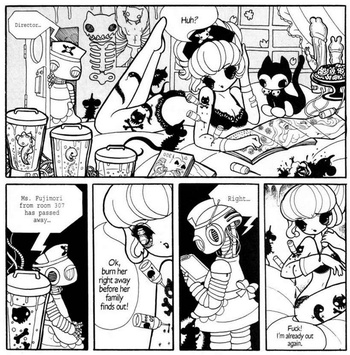

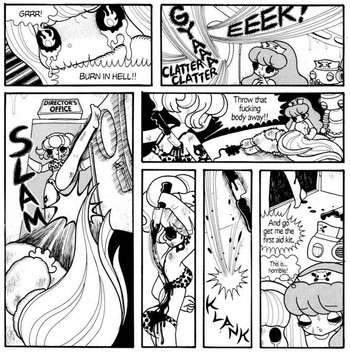

In the post-WWIII far future, humanity lives in domed cities, surviving on nutritional capsules called "Pure Trance." But overeating is a problem, and people often puke up thousands of pills and die, while other people live for a taste of black-market animal meat. Center 102, a hospital which mostly treats "Pure Trance" eating disorders, is run by Director Yamazaki, a sexy blonde in black lingerie with a little skull-and-crossbones on her nurse's hat. Yamazaki is a drug addict, a sadist, and a really sloppy doctor, who accidentally kills one patient by leaving a porno magazine inside her body after surgery. ("You stupid bitch! My daughter that YOU operated on died yesterday! And THIS came out of her stomach from the autopsy!") She lounges around bed all day with hypodermic needles sticking out of her body, served by her staff of robots and nurses, who, like her, are all long-legged, sexy women. Her second-in-command is Kimiko, a scarred tough-girl type who swears almost as much as the Director. ("Don't talk back to me, bitch! Hurry up and prepare my meal! Now! I'm fucking starving!")

Kaori, the only nurse with a conscience, is the frequent target of her bosses' violence. She spends a lot of time being tortured by the Director, with whips, blades, chainsaws or force-feeding. Her pneumatic body is covered with scars. ("Poor Kaori…she's too hard on you," one of the robot nurses consoles her. "Thanks, but I'm used to it!" says Kaori.) Things get worse when the Director makes two artificial nurses, Takeko and Umeko, who turn out just as bad as their creator and like tying up child patients so the rats can crawl on them. When the Director plans to kill four children and turn the twins into earrings, Kaori can't take it any longer; she takes the children with her and flees flees to the surface world, a radioactive wasteland filled with heaps of trash and inhabited by mutant animals and floating brain-creatures. The rescued children grow up into hunter-warriors who wear fur bikinis and hunt with a bow (Sheena, Queen of the Junglestyle), and one of them falls in love with one of the brain-creatures. Meanwhile, Kimiko, Takeko and Umeko are sent up to the surface to find Kaori and take her back for punishment. ("Since she is against the Director, from now on she'll only live to be tortured forever!")

This is just the first half of Pure Trance. Like a Tezuka manga, it wanders all over the place, and it must have seemed even crazier reading it in CD booklets; narratively, it has some weak spots, but that seems to come with the territory of a trippy, grindhouse story like this. (The graphic novel version includes useful 'trivia' sections in the extra-wide margin, which help a lot with following the plot.) After Pure Trance, Mizuno's next works were three loose fairytale adaptations: Cinderalla, Hansel and Gretel and Princess Mermaid. Mizuno has said in interviews that the fairytale plots were forced upon her by her publisher, but they're still good stories: in Cinderalla the evil stepmother and stepsisters are zombies who run a yakitori stand; in Princess Mermaid, the best of the three, the mermaids live in a brothel under the sea until one of them falls in love with a human who works at a foul fish-processing factory. Like Hans Christen Andersen's original Little Mermaid, it's an agonizing, emotional story, with a tighter narrative than Pure Trance—and this is the hidden secret of Mizuno's comics: they really do have drama and good storytelling, in addition to their artistic surface appeal. Little Fluffy Gigolo Pelu, her latest work in progress, is the story of an adorable alien fluffball who travels to the Earth in search of the woman he'll marry, innocently inserting himself in the tragic love lives of hapless women, one after the other. The look of Pelu is based on Fujiko Fujio's Mojacko, but the stories are an affectionate homage to the 36-year-long Tora-san film series, about an eternal wanderer encountering sentiment and sadness, and of course drug overdoses and vomiting space hippos and flaming death.

Artistically and story-wise, Mizuno, too, seems like an alien. Of course work so individualistic would never be published in a "shojo" or "shonen" manga magazine, but more than that, her work defies categorization by the clichés of stories for "women" or "men." Mizuno's comics are full of traditionally "female" concerns—pregnancy, cosmetic surgery, eating disorders, fashion, food—combined with traditionally "male" fascinations such as half-naked catfights, gore and showing women's breasts whenever possible. It's in the spirit of Russ Meyer's Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! and women in prison movies (both early 1960s tropes—Mizuno loves the '60s). But no matter how many exposed DD-cups there are in Mizuno's work (not to mention zombie women tearing off their own breasts spilling forth spiders and worms and snakes), it's clear the women are the really powerful ones. Her art is sexy and cute, but it lacks any sense of the pure, the demure, the blushing maidenly come-hither look that makes moe fans' hearts (or whatever) throb. Unlike manga artists working in commercial magazines, she never draws women with blank plastic crotches: their pelvic areas are ornamented either with suggestive objects like a heart or a flower, or with pubic hair like curving flames. (Or musical notes, in one lovely drawing.) And although her women are beautiful violent dolls, her male characters are soft little cartoons of men that make Leiji Matsumoto's potato-people look like Jotaro from Jojo's Bizarre Adventure. There are no handsome bishonen in her work; at least, none that the readers could take seriously. In Little Fluffy Gigolo Pelu, the romantic lead makes the discovery in the first chapter that he's not even a complete person: he's more like a fluffy little gonad, an internal organ that was accidentally dislodged from the body of a member of a parthenogenetic all-female race. "Does that mean I'm just a part of somebody's guts?!" Pelu says, white with shock. THE MAIN CHARACTER OF LITTLE FLUFFY GIGOLO PELU IS AN ANTHROPOMORPHIC TESTICLE. (Or maybe ovary.) And you thought the love interest in Ceres: Celestial Legend was Freudian.

Junko Mizuno's manga output has never been big compared to her fine art and illustration, and Little Fluffy Gigolo Pelu is shaping up to be her longest manga. But until the epic second and third volumes of Pelu come out, Pure Trance is a taste of Mizuno at her rawest and trashiest, and it's great. Her women may be hungry spread-legged girls with their hands full of meat and syringes, but they are completely in control. Her manga is a strange hardy plant that's rooted in the oozing muck of pin-ups and soaplands and internet porn and all the other ways that pop culture makes toys and dolls out of women. If I were making a feminist meme, I'd use Junko Mizuno instead of Ryan Gosling.

discuss this in the forum (15 posts) |