Fighting for a Better Anime Industry - An Interview with Animator Supporters' Jun Sugawara and Genga-chan

by Coop Bicknell,

According to Animator Supporters' founder Jun Sugawara, these regular departures and a headhunting culture developed by larger studios such as A-1 Pictures have led to a troubling brain drain among the Japanese animator community. The practice allegedly started around 2010. This is now considered a bad practice at any anime production company. Veteran animators were snapped up from smaller studios, leaving them unequipped to educate the next generation. It was also around this time that then-CG artist Sugawara said to himself, “This isn't normal,” and founded Animator Supporters—a nonprofit organization that offers housing assistance, career assistance, and mentorship to blossoming talent through their Animator Dormitory program. In the organization's almost fifteen years of operation, seventy-seven talented creatives have walked through the dormitory's doors. Some of these talents have gone on to work on huge titles like Chainsaw Man and Gundam, but others have unfortunately left due to the very same issues the organization has been tackling.

In addition to Animator Supporters, other organizations like the Terumi Nishii-founded NAFCA have appeared to join them on the front lines of their shared advocacy and education efforts. However, according to Mr. Sugawara, the progress on real change is still slow-rolling. He has also heard calls from international supporters for a union, but the NPO founder has always been quick to share the Japan-specific difficulties of such an undertaking. To quote Mr. Sugawara, “It's not so easy.” Fortunately, some studios have been making headway on the dire situation. Sugawara shared that CloverWorks, the studio behind Bocchi the Rock!, went out of its way to hire an animation director who would serve as a mentor to their younger animators. While at Otakon last year, I'd heard a similar sentiment from The Wrong Way to Use Healing Magic director Takahide Ogata regarding that title's production at Studio Add.

After fifteen years of operation, Mr. Sugawara feels that Animator Supporters has established a strong base for itself. However, he also dreams of opening an American anime studio one day—bringing animators from across the Pacific Ocean to create amazing new projects while being provided with proper union protection and fair pay. But given America's current geopolitical situation and the troubles of its own animation industry, I quickly referred Mr. Sugawara to the Animation Guild—an American union that's been assisting creatives in the aftermath of the destructive LA fires and their industry's job-cutting cataclysm.

As someone who wouldn't be where they are today without the talents who make animation happen, I felt a strong sense of responsibility well up within me when I sat down for an extended interview with Mr. Sugawara at this year's Animazement convention. Alongside one of the Animator Dormitory's current residents, Genga-chan, we talked about the realities of working as an animator today, what led the industry to this point, and the solutions that are being considered to help fix these issues. Translator and regular Animator Supporters collaborator Darius Jahandarie served as our interpreter.

Sugawara-san, for those just hearing of your efforts for the first time, what is the mission of Animator Supporters and the Animator Dormitory? What do you do for the new animators who come through your doors?

Jun Sugawara: To start, the working environment in Japan is pretty bad overall. In particular, it's very bad for animators, and there are many reasons for that in terms of our societal structure and the presence (or absence) of unions. For example, there's a payment structure for in-between animators in which they're paid 200 yen [roughly US$1.39] per drawing.

Oof.

SUGAWARA: It's pretty bad. I've been running Animator Supporters since 2010, so almost fifteen years now. The people we support aren't randomly chosen, but rather, they're animators who we believe to be quite good. Going back to that payment model, a really, really good in-between [douga] animator can maybe do 300 pages a month at the most. Genga-chan probably can't hit the full 300 herself. So, there's a very limited number of animators who can do it. Even if you can, it would total out to 60,000 yen [roughly US$417.59], which is barely even enough to rent a single tiny room.

When I started the organization in 2010, I was graduating from an art school, Musashino Art University in Tokyo, with a focus on CG. Some of my younger classmates occasionally asked me, “Hey, could you teach me a few things about CG so I can get a job in that field?” I also worked with Tomohisa Shimoyama-san, who's most well-known for working on Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood. Both of us were helping out and teaching the others around us. The people I taught CG animation to were generally able to get jobs. Meanwhile, the folks under Shimoyama-san were taught so well that they became good at animation. However, the jobs they'd end up getting would only pay around 30,000 yen a month [roughly US$208.80], so they ended up quitting. They just couldn't sustain themselves even though they'd been taught well.

I see this situation, and I think, “This is bad... It's weird, right?” As I looked into it further, I realized that it's a very deeply rooted issue—it's not a surface-level problem. One of the contributing factors to this is the existence of production committees. The way these committees profit is by running very cheap productions and operating lots of them. And if they want to run a cheap production, one way to do that is to reduce the cost of in-betweening.

What have been some of the major successes of your organization's work?

SUGAWARA: In terms of our organization, we started by supporting certain animators with their living situations. How we did this wasn't arbitrary, so we selected animators based on the value we believed they would have as they continued to grow. We did that by holding an animation contest, the Animator Grand Prix, where we had people apply to join, and industry members judged it. Some of our judges were Naoyuki Asano, an animator on Osomatsu-san, and Shingo Yamashita—these folks served as judges and heads of the dormitory.

The first person who joined was Shingo Tamagawa, who is an animator involved with a couple of different works like Gundam Reconguista in G, Mobile Suit Gundam Hathaway, and Puparia. He does a lot of character animation direction, especially with Sunrise.

Genga-chan, what initially drew your attention to Animator Supporters and Animator Dormitory?

Genga-chan: I first learned about Animator Supporters through the internet and learned about the dormitory through the Animator Grand Prix.

What has your experience in the dormitory been like over the years? What are the general vibes between you and your roommates?

Genga-chan: When I first heard it was a dormitory, I imagined an apartment building with separate rooms. But in reality, it's more like a traditional house.

SUGAWARA: Like your grandma's house!

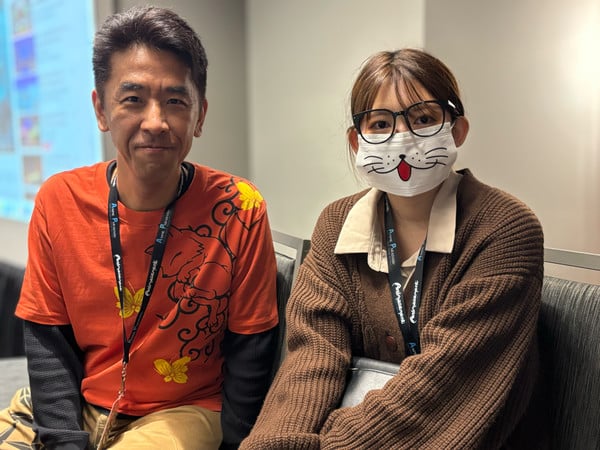

SUGAWARA: It's this house, and these are the students. Genga-chan's on the right, and Tanaka-san, another one of our students, is on the left. Tanaka-san is quite talented herself!

Genga-chan: I have a great relationship with Tanaka-san! Even in our private time, we might go out to get something to eat or grab dinner together. We get along very well.

How did your parents react when you decided to become an animator?

Genga-chan: Making a living by drawing pictures is, even in my opinion, not something I was able to fully visualize in my mind. And my parents even more so. They were quite surprised and opposed to it.

I was a theatre student in college, so I know the feeling.

Genga-chan: Aaaaaah.

What are some of the challenges you've faced in your career so far? And how has the dormitory prepared you to face them?

Genga-chan: For the last year, I've been working on a music video, and it's been challenging. [Chuckles] I'm doing the layout and the keyframes, so it's been quite challenging when you need to look at the storyboard and just make it all yourself from there. The amount of work I'm doing on this is huge.

SUGAWARA: Actually, the difficulty level of this project is probably higher than one would normally want to assign to a new animator.

Genga-chan: Yep.

I see.

SUGAWARA: Given that my background is in CG, I made the original storyboards from a CG artist's perspective. But that made it a bit hard to implement, because there are some differences between CG and hand-drawn animation implementation.

Sugawara-san, how does the Dormitory Program tackle the topic of burnout? In addition to dealing with harsh deadlines, I'd imagine there's been a discussion about those who want to work late hours because they love what they do, but they're not considering the toll it will take on them.

SUGAWARA: The problem is that we don't have enough animators. There's a statistic that almost 90% of people quit within three years of joining the industry. Part of the reason is the low wages. Other than that, you're alluding to the psychological part of the problem. For example, power harassment is a big issue—it's where people are harassed by their seniors, fall into a depression, and end up quitting because of it.

Something we're currently pursuing as an alternative strategy to avoid burnout is a project we're working on with Terumi Nishii, Jujutsu Kaisen's chief animation director. Since 2023, she has been serving as the animation director for the music video of a short anime currently in production under the project title "Raising Anime Budgets and Providing Training – A Collaboration with Aya Hirano." She is also in charge of mentoring Genga-chan. In addition, she has been instrumental in helping us assemble a team of veteran staff for direction, animation checking, finishing, and more. One of the strategies we'd developed was for our dormitory students and graduates to avoid working on normal TV anime projects with strict deadlines. Instead, we'd help them find projects that had longer deadlines and better pay. For example, these would be projects that are released on YouTube, are crowdfunded, or something similar, to ensure a better working environment. The big problem is the production committees. We're trying to figure out an alternative funding model. One that the fans can crowdfund, and let us do a one-off anime.

Similar to OVA [Original Video Animation]?

SUGAWARA: Yes, yes, yes! [In English] Exactly! Something OVA-like, maybe a 25-minute project that's properly funded.

Genga-chan, how do you and your fellow animators deal with burnout? Are there any tools you've picked up from the dormitory program to help you face it?

Genga-chan: One thing I make sure to do is value my private time. If you don't take care of yourself and your health, it becomes a mental health issue.

Sugawara-san, a couple of years ago, I was listening to an interview with Noboru Ishiguro on the production of the original Macross series and he said that it was something of a miracle that they were able to finish it given the industry's low wages and working conditions. Flash-forward to today, and it doesn't seem that the industry's conditions have significantly improved in the last 40 years. Given the fact that conditions shift from workplace to workplace, is that assumption accurate?

SUGAWARA: There have been some changes, partially due to the work of Animator Supporters and other groups. One interesting dynamic is that, within Japan, the fact that animators aren't properly paid doesn't come up often. It might occasionally be covered on social media, and people will get mad, but there aren't many people working to fix the fundamental problem. However, in America and the West, people are getting angry on our behalf—they have a stronger sense of justice. Due to that, it's a frequent occurrence for something to be covered on social media, and it'll reach the attention of industry heads due to the people in America who are supporting us.

When it comes to the larger production companies in Japan, there have been some improvements. Previously, the fact that animators were paid so poorly was almost covered up, being hidden by companies to the point where if someone were to talk about it, they might be fired. That was the sort of situation at the time. Due to our work and the many Americans bringing these issues to light, that has improved. Now it is becoming a more well-known issue that's being recognized as a problem. As a result, some of those larger companies are now a bit better at properly dealing with the situation.

Since I mentioned Ishiguro-san, I wanted to ask. Is there a prevailing thought of “the industry is what it is” among veterans? How do you push back on that notion?

SUGAWARA: Yes, it is a problem. Since there are fewer animators in the industry now, some of the veterans are paid better due to supply and demand. For example, they'll be paid to finish their existing work and the like. A related problem is that these talented animators will sometimes be pulled from one company to another, precisely because they're talented veterans. In that situation, there might not be any strong animators left at the smaller company they were pulled away from. It becomes very hard to nurture the next generation, and this has been a problem since 2010. Some new animators who would've joined around that time would be in their thirties now, but they might not have had someone to teach them and take them under their wing.

Would you say that the industry has become more geared toward getting out the next product instead of ensuring that this field will be around for years to come?

SUGAWARA: Exactly. It's been the case for many, many years now that everyone has just focused on trying to finish their existing work, so they're not able to think about anything else. And, of course, what we're discussing here [the headhunting of veterans] started around 2010, so it's been almost fifteen years. So many animators haven't received proper instruction in that group. That puts us in the situation where someone who doesn't understand grammar is writing a novel.

Animation directors are currently taking the illustrations given to them and fixing those drawings from scratch. Compared to the '90s, where the entire team was quite talented—the key animators, inbetweeners, and in-between checkers—the animation director was taking something good and making it a little bit better. Currently, they're taking a poor-quality keyframe and bringing it up to just passable. As a result of that, the directors are taking a lot of time to do their corrections, and sometimes the schedules don't fit. To summarize, we haven't been able to do a proper generational handoff from the old to the new.

Whenever stories of crunch and untenable work conditions hit the animator community, be they big stories like MAPPA's troubles with Jujutsu Kaisen or small ones that are privately shared, how do they tend to process the news? How does that affect morale? Do they hope that speaking out is going to make a change? Or that it's perhaps another story that people will forget about?

SUGAWARA: [Nervous chuckles] Regarding MAPPA, it's said there's a rule that you're not supposed to talk about it.

Genga-chan: It's difficult, so people tend to keep it bottled up and don't necessarily talk about it.

SUGAWARA: Most people who work in animation are fundamentally artistic, and a weird fact of the situation is that a difficult environment can sometimes lead to greater artistic work. There's an irony in that perspective. But unfortunately, such methodologies are unsustainable, and they result in people quitting.

What's one reality of living and working as an animator that you'd like the readers to know?

Genga-chan: Many people assume that you need to be insanely good to get your foot in the door. But actually, animation is the sort of industry where you get in, and then you become good after a decade or so of working in it. You don't necessarily need to be super good from the get-go. Sometimes, a very talented person enters the industry, gets burned out, and leaves. And other times, a person who isn't necessarily a super genius will enter, but they stick around for ten or twenty years. It's the people in that latter group who end up leaving great work behind. I'm also not great [chuckles], but I'm doing my best to stick around and be part of that group.

SUGAWARA: We're not in a great place right now. There are not enough people around. In particular, there are no great animation directors or key animators. And for in-between artists, there is no one left in Japan—it's all being outsourced to other countries. This is a very different situation from the '90s, where you could find good people working in those roles, and therefore, you could easily produce good work. Of course, there are the occasional good title or two being made to this day, but that's done by using money from a big production to assemble talent from other studios. However, that's very rare.

With recent series like Shirobako and ZENSHU. highlighting some of the external and internal struggles of working in the anime industry, do you think they've helped viewers start to understand what animators go through day in and day out?

SUGAWARA: Yes! In particular, I believe that Shirobako in particular is very, very well done. However, one thing that Shirobako isn't being honest about relates to its lack of any in-between representation. The show's story involves many key animators, but it's the in-betweeners who find themselves in the worst situations. And it's an issue because this problem has been going on for many, many years, but no one has done anything about it.

There's another anime called Paranoia Agent by Satoshi Kon that has a particularly frightening look into things. I recommend that you check it out; it's very honest about the reality of the situation. With more recent productions, the laws have slightly changed, so the situation is improving a little bit. But the older productions operated with much fewer restrictions, leading to instances where people would work all night, very long hours without any sleep. There were even some cases where we heard that people would get into traffic accidents due to these work practices.

What is next for Animator Supporters, and how can the readers keep up with you?

SUGAWARA: Our work up until this point has involved our housing efforts and the like, but this is like putting a Band-Aid on the wound, so to speak. To fix the more fundamental problem at play, we need to create more properly paying work for people. That connects back to the topic of OVAs we talked about earlier. We also need to level up our people, not just key animators, but animation directors are lacking at the moment as well. In order to help them grow, we're bringing in more and more talented animation directors to help teach our students. For example, we've brought in Terumi Nishi from Jujutsu Kaisen 0 and JoJo's Bizarre Adventure alongside Kazushige Yusa, who will be joining us in August. However, it's not just animation directing, but art direction too, as Yuki Funagakure—a very talented artist—will also help us. He's worked on a show called Oblivion Battery.

For more information on Animator Supporters, check out their Website, X/Twitter, Patreon, and YouTube Channel.

Special Thanks to the Animazement Staff for facilitating this interview and Mr. Jahandarie for his linguistic expertise.

discuss this in the forum (2 posts) |