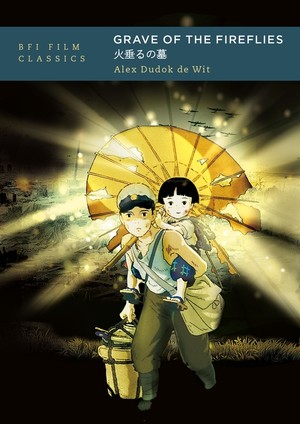

Alex Dudok de Wit, Author of BFI Classics: Grave of the Fireflies

by Andrew Osmond, Alex Dudok de Wit's new book study of Isao Takahata's Grave of the Fireflies is published in the British Film Institute's BFI Film Classics range, and offers a fresh appraisal of one of the most acclaimed anime films. The book emphasizes that Takahata did not make the film to reduce viewers to tears. Instead the director hoped that younger generations would think critically about their modern lives. Dudok de Wit delves into Grave's production and analyzes how Takahata modified the original prose story by Akiyuki Nosaka. He also discusses whether Grave reflects a mentality that Japan was the "victim" in World War II.

Alex Dudok de Wit's new book study of Isao Takahata's Grave of the Fireflies is published in the British Film Institute's BFI Film Classics range, and offers a fresh appraisal of one of the most acclaimed anime films. The book emphasizes that Takahata did not make the film to reduce viewers to tears. Instead the director hoped that younger generations would think critically about their modern lives. Dudok de Wit delves into Grave's production and analyzes how Takahata modified the original prose story by Akiyuki Nosaka. He also discusses whether Grave reflects a mentality that Japan was the "victim" in World War II.

It was great to read about the original Nosaka story, and about how it differed from the film - for example, in its more nuanced treatment of the adult characters. The story is often referred to as a novel; about how long is it really? Do you think there is any hope it will ever be translated into English? – I'm not aware of any translation to date.

There is in fact a translation, by James R. Abrams. It's sequestered in a 1978 issue of the journal Japan Quarterly (under the title A Grave of Fireflies). Pushkin Press, which has put out translations of other Nosaka stories, has announced a new translation of Fireflies, but it isn't clear when that's coming out.

Abrams's translation is around 12,000 words, so it's a long short story or a short novella. With its rich psychology and complex structure — a narrative spanning months, flashbacks within flashbacks, etc — it feels more like the latter to me. There's another term for stories of this length, the “novelette”, but as that word has often connoted light romantic tales, it didn't feel right for Fireflies!

The novella is a tough read, not just because of its harsh story, which Takahata's film alleviates by adding more moments of joy and beauty. Nosaka's prose is knotty, stream-of-consciousness, idiosyncratically punctuated, brimming with detail — that's his style. It's a remarkable read, and must have been bloody tricky to translate. Abrams did a fine job, I think.

You talk about how Takahata's own war experiences informed the film, and emphasize its romantic sensibility. Do you think that it might be Takahata's most personal film?

Quite possibly. Takahata would say the firebombing he endured as a child was the most difficult experience of his life. Making the film, which plunged him back into those memories, must have been difficult too. When Studio Ghibli was founded, Takahata didn't initially plan to direct a film there, and this was the project that convinced him to do so. It was clearly very meaningful to him.

There are other candidates: Pom Poko, which is more of an original Takahata story than his other features; Gauche the Cellist, which was produced independently across five years; Kaguya, which took even longer, and which he'd been mulling for decades. That last film hums with the wisdom of an artist nearing death. But he invested himself so deeply in all his works that you could make a case for any of them as his most personal!

Linked to that, I'm wondering if Takahata's closeness to the material — and especially his personal knowledge of what wartime Japan was like — might be linked to the way that he seemed to misjudge how 1988 audiences would react to Grave. Do you think there might be such a link?

Takahata lived through not just the war but also the wrenching U-turn in official ideology that followed: suddenly, the politicians and teachers were preaching American-imposed democracy and pacifism, not Japanese imperialism. I think that experience led many of his generation to be skeptical of authority, to question how society works, and this carried through the decades of political protest that followed.

Japan had certainly changed by the 1980s, and Takahata worried that children were now growing up too spoilt by consumerism, too self-absorbed. In this sense, he saw a similarity between them and Seita, who rebels against the social customs of the time by rejecting his community. He hoped his young viewers would also see something of themselves in the character, and be prompted to think about how they live their lives. He may have overestimated how ready they were to take the film as social commentary, as opposed to a pure tragedy.

I grew up in the stable, wealthy UK of the 1990s and 2000s, and war seems very remote — almost alien — to me. I find it hard to judge the actions of well-meaning civilians caught up in that kind of nightmare, which is kind of what Takahata was hoping his viewers would do. They may have felt the same as me. On the other hand, Takahata expected that people who'd lived through the war would find Seita's behavior unrealistic. He was surprised at how many of them were moved by the film.

In your book's last pages, you are critical of several other anime films that deal with World War II, which tend to have a victim mentality. I wondered if you thought the film In This Corner of the World was any more interesting than them?

I like the film. The story is ambitious in that it spans many years, and that era is portrayed with lovely detail. I also find it a bit plodding: as with many of these films, it sometimes feels like the narrative is being driven by the progress of the war more than by any clearly defined character arc.

There's depth to Suzu, the protagonist, but overall I think she and the other characters slip into the trope of the victim. They suffer the consequences of the war, but seem almost completely disconnected from the circumstances that caused and sustained it — including the imperialist ideology that underlay popular support for the whole thing. The only characters who seem to subscribe to this are the military police, who are cartoonishly evil.

To be clear, I don't think the Japanese have a unique duty to do penance for the war. Honoring those who suffered and died in wartime is a natural thing, and all countries do it. But Fireflies does something unusual for the war anime genre: in Seita, it has a character who is sympathetic but also a dyed-in-the-wool imperialist, which is what a 14-year-old exposed to constant propaganda would be. The film intelligently hints at how that belief system contributes to his bad decisions. It tells us something about the nuances and contradictions of human behavior.

I should say I haven't seen the extended cut of In This Corner of the World.

This is a horrid way of putting you on the spot, but you make clear how different Takahata's and Miyazaki's philosophies of storytelling and filmmaking were by the time Grave was made. Do you, like many fans, see Takahata as a fundamentally greater artist than Miyazaki?

I don't — the two filmmakers are equally great in my eyes. They shared many convictions yet expressed them in very different ways, so comparing their films is endlessly interesting, even if that's far from the only way to look at their work. It's especially fun to juxtapose Fireflies and My Neighbor Totoro, the original double bill. They were marketed to Japanese audiences as a joint statement on a bygone Japan. There's a lot more that binds them than first meets the eye, and I think there's a strong streak of Takahata in the way Totoro depicts the girls going about their daily activities.

What strikes me is how comparatively uninterested English-language scholarship is in Takahata. He may not have the mega-blockbusters or Oscar, yet he's a director of rare genius, many of whose works are well known and widely accessible. Where are the books about him? I'd like to see his weighty collected writings translated, too.

I was fascinated to learn that the pond and the (blocked-up) bomb shelter which inspired Nosaka still exist today. Have you visited them yourself, and if so, were there other tourists there? You mention some tourists do visit the pond, despite the film's bleak subject.

I've never visited the pond — I haven't been to Japan since I started writing my book. But when I looked up its location a few years ago, I was amazed to find it's within walking distance of Kwansei Gakuin, the university I attended for a term in 2009. For four months, I unknowingly roamed the same streets as Seita. My walk from the station to the campus passed through a neighborhood, Nigawa, that's referenced in Nosaka's story! It has all changed beyond recognition, of course.

Last June, a crowdfunded monument in honor of Nosaka's story was unveiled near the pond. The placard features a bit of pre-production artwork from Takahata's film. So now there's an official pilgrimage site.

You talk about Border 1939, the war drama that Takahata envisaged making after Grave. It sounds like a fantastic story [Dudok de Wit wrote an article about it]. Do you think there's any chance that Ghibli might release any more material about it in the future?

When I wrote about Border 1939 for Little White Lies, I contacted Ghibli, who were unable to provide material that wasn't already published. There's little information on the project out there. With Takahata now gone, few people may now be in a position to say much about it at all.

Sadly, Takahata is no longer with us. Did you ever have the opportunity to speak to him; and if so, what were your impressions of him?

I met him twice. The first time was at the Hiroshima Animation Festival, where we didn't speak much. I met him again in Japan in 2016, around the release of my father's [Michael Dudok de Wit's] film The Red Turtle, on which Takahata served as artistic producer.

He was kind, reserved at times and talkative at others. We spoke of Spielberg, Japan's syncretic religious practices, and The Simpsons (he wasn't a big fan). He put me on the spot by ordering raw horse sashimi for me in a restaurant. In conversation he'd occasionally drop in a few words of French, knowing I speak the language (he did too, very well). He was in high spirits, and when I learnt of his death a year and a half later, I couldn't square the news with my memories of him.

Soon after Takahata's death, it emerged that Toshio Suzuki had made blunt comments about Takahata's working relationship with his subordinates, and especially with Yoshifumi Kondō, who was the character designer and animation director on Grave of the Fireflies. The comments were reported by ANN.

Do you have any comment about what Suzuki said? For example, did they affect the way you regard Takahata; or do they shed any light about his attitudes and beliefs that are embedded in Fireflies?

Takahata was a famously demanding director — that's clear from the account I give in my book of the making of Fireflies. But these specific comments from Suzuki are problematic, as Suzuki kind of retracted them later on. They were initially published in an essay about the production of Kaguya, but when Suzuki's production memoirs were anthologized in a book (Tensai no shikō: Takahata Isao to Miyazaki Hayao, reviewed by Dudok de Wit here), this essay was left out, Suzuki explaining in his afterword that he had written it when "my emotions weren't in order" and now worried it might cause misunderstandings.

There's a bundle of first-hand testimonies about the making of Fireflies, and those formed the basis of my research into the film's production.

discuss this in the forum (4 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history