Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Swan

by Jason Thompson,

Episode XXXVIII: Swan

"Most people are surprised to look through opera glasses and see that the sweetly smiling prima ballerina is actually drenched in sweat from the exertion."

-- Kyoko Ariyoshi, Swan

I didn't expect that a shojo manga about ballet would be one of the most fiery-spirited shonen manga I've read in the last few years. Blood and sweat, competition, agonizing training sequences -- these are things that are more common in boys' manga, but Swan transfers them to the ballet and somehow makes it a perfect fit. It's a mixture of rivalry and hard work, art and elegance; a combination of yûjô, doryoku, bigaku. Perhaps it's a product of its times; in the 1970s and 80s, the Japanese economy was booming, and shonen manga was full of Horatio Alger-esque inspirational stories of boys struggling to succeed in professions like sports, cooking, fishing, photography, selling household appliances, and so on. (I also just found out from Wikipedia that Horatio Alger may have been gay, which makes the comparison even better.) It's only natural that shojo manga shared the same hardworking spirit. Japanese media commenters in recent years have complained that Japanese boys are turning into "herbivores", lacking the manliness and self-sacrificing work ethic that characterized their father's generation. I don't know if this is just stereotypes, but judging purely from Swan, Japanese girls in 1976 were 10 times more badass than men in most countries today.

Kyoko Ariyoshi, the mangaka, is obviously in love with ballet; after the original 21-volume Swan (15 volumes of which were translated by the now-defunct CMX), she went on to draw a sequel and many other ballet-focused stories. In contrast to some other ostensibly occupation-based manga like Mixed Vegetables and The Magic Touch, which contain virtually zero information about cooking or massage, Swan is full of fascinating ballet trivia. If you don't know the definition of ballet terms like a pas de deux or a grand jeté, you will know them after reading this manga. You'll also know all abot the great classical ballets of the 19th century, which the characters perform, one after the other, with helpful descriptions by Ariyoshi. Real-life ballerinas like Yoko Morishita, Margot Fonteyn and Maria Plisetskaya, who sometimes show up in cameos, give the manga an extra feeling of authenticity. Swan is so associated with ballet for manga readers of a certain generation, it lives on today in Swan Magazine, an ongoing quarterly featuring a mixture of Ariyoshi's manga together with with ballet news and interviews.

I didn't know anything about ballet when I first read this manga, but I quickly got into it. Masumi Hijiri, our teenage heroine, is a cheerful girl who lives out in the sticks in Hokkaido. She lives with her dad, a sculptor with an enormous 1970s mustache, but her mind is always on ballet, and she dreams of becoming a great ballerina like her deceased mother. (The 'following in her mother's footsteps' thing is just a background detail; it's clear that Masumi loves ballet for its own sake, and not just to take care of her mother's baggage.) But it's not easy studying ballet out in a rural classroom where farm animals occasionally run through the rehearsal studio. Masumi loves ballet so much, she travels all the way to Tokyo to see a special performance by visiting Russian dancer Alexei Sergeiev. The ballet is sold out, but she forces her way backstage, where she runs into the performers. She is so stunned to meet them that she can do nothing but express her emotions through ballet, in an impromptu attitude en pointe, before the security guards hustle her away.

Luckily for Masumi, her spontaneous dancing intrigues Alexei, who thinks she has natural talent. The Russian dancer invites her to participate in a special national ballet competition for which he is one of the judges, and before she knows it, Masumi is attending a special ballet school in Tokyo. There she meets a bunch of rising ballet superstars who become her friends and rivals. Kyogoku Sayoko, an elegant, slightly older girl, takes Masumi under her wing and tries to teach her how to be a better ballerina. Aoi and Kusakabe, two of the male students, become Masumi's friends and try to make her feel at home. But it's not all fun and games at ballet school. Alexei Sergeiev, whose skill is compared to Rudolf Nureyev, becomes Masumi's personal coach. Furious at the idea that she might squander her natural talent, he leads her in a harsh training regimen, taking her to the edge of collapse.

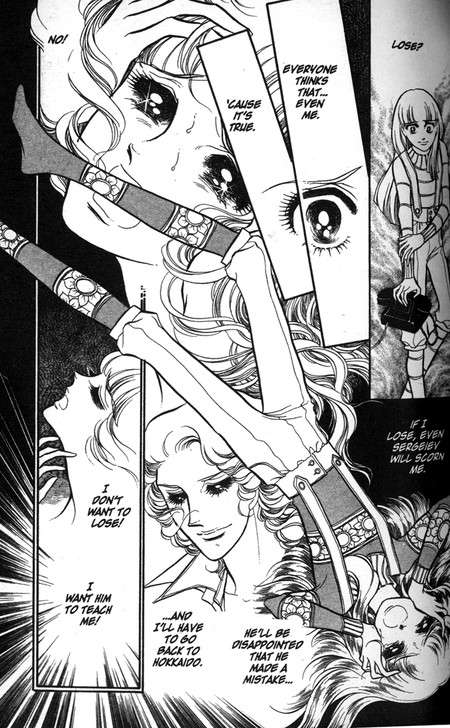

"The beauty of ballet is based on grueling daily lessons and mental discipline!" Kusakabe tells her. Masumi trains all night long. She wears out pair after pair of ballet shoes. Her feet blister and bleed. (Remarkably, there's not so much of that old shojo manga cliché of the jealous rival putting tacks in the ballerina's slippers. She injures her feet all by herself.) "Dancing one scene is as tough as a 100 yard dash!" she thinks. Later, she dances so much in competition that she almost passes out. "I can't see or hear anything anymore. So much sweat…my body feels as heavy as lead…" Onward she struggles, despite the pain. "I want the harsh world of ballet! I want it more than ever! I want to take this passion and pour my heart and soul into my training!"

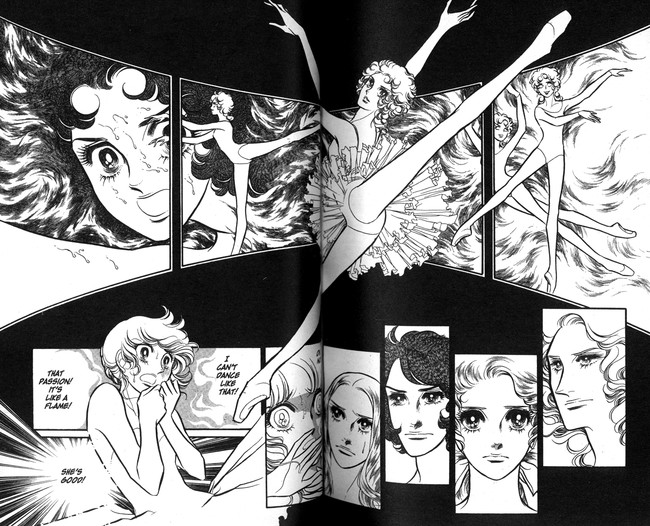

If the training in Swan is like a shonen manga, the ballet scenes are the fights, and it's here that Swan is really unique. Everyone who's read manga is used to a certain visual vocabulary, developed since 1950 or so, for how action is drawn -- the speed lines, the use of spread pages and big panels, the panels showing someone just before their fist hits someone or just after the other person goes flying away, but rarely the moment of impact. There were other ballet manga before Swan, but I presume the field wasn't as crowded as fighting manga, and Ariyoshi uses her own original techniques for depicting ballet's own, beatdown-free celebration of the human body. Instead of speeding up time and putting us in the red shoes of the ballerina (except for a few important moments), she puts the reader in the position of the audience. Time stands still as we appreciate the beauty of the human figure in motion. Ariyoshi draws the figures as they leap and pirouette and pose, like little film strips; she obviously sketched actual ballet dancers and probably owned a lot of ballet photo books. (Did she have a VCR or movie projector in her studio to watch ballet films, way back in 1976?) Unlike many fighting manga, the ballet never gets superhuman; sometimes the ballerinas make it look so easy, but other times you appreciate how strong and flexible and limber they have to be to get into those poses. (No wonder ballerinas often start training at the age of three.) Ariyoshi's great figure artwork is enhanced by her amazing page compositions; essentially, she turns each dance scene into a series of expressionistic illustrations, visuals which help the imagination fill the gap left by the missing movement and sound. (For a counter-example of a manga which doesn't manage this, take Nodame Cantabile, which never quite makes me imagine I'm listening to music). Swan captures the joy of dance in the same way that sports manga captures the excitement of a goal and battle manga captures the feeling of having the crap kicked out of you. "Ballet is not a tournament!" one teacher tells a student who gets too aggressive, one of the only lines I think Ariyoshi wrote with a wink.

There's romance in Swan too, at least a little. When her classmates talk about their boyfriends, Masumi thinks "A boyfriend, huh…I guess the rehearsal studio is my boyfriend." Several flesh-and-blood boys have the hots for Masumi as the series goes on, and she isn't entirely immune to their charms, but it's more about friendship and rivalry. There's the faintest scent of yuri—though, I suppose, no more than the boy-on-boy action in the typical shonen manga—in the scenes when experienced older woman Kyogoku takes care of sweet little Masumi, until she finally realizes that Masumi will grow up to be her rival ("I always knew this day would come…to feel this fear, and this strange thrill! I've finally met my true match!"). And of course, there's some chemistry between Masumi and Sergeiev, who is pretty handsome, like many "coach" characters in '70s shojo manga. ("I work *so* much harder when Sergeiev-sensei is watching. How naughty of me!") But Masumi, unlike many shojo heroines, doesn't need love as an incentive to be awesome.

Indeed, for the heroes and heroines of Swan, drawn in Japan's booming 1970s, their motivations for ballet are more than personal. As the characters themselves repeatedly say, ballet wasn't so well known Japan at the time, and they feel a duty to make it more popular—and to prove that Japanese ballerinas are among the best in the world. "We're going to make ballet more special in Japan! Together, I know we can do it! I know we can!" one character vows. "I want to produce a world-famous Japanese ballet -- for the Japanese!" another says, reminding me of scenes in Iron Wok Jan when the characters vow to make a new kind of Chinese food that Japanese people will like better. Like the Olympics, or manufacturing cars, ballet is an expression of national pride. When Sergeiev wants to motivate Masumi, he tells her "Don't you hate the idea of being left behind? Of the entire world of Japanese ballet being left behind?!" There's a hint of an internalized inferiority complex in the scene when Sergeiev tells Masumi that she must train harder than a European; according to Sergeiev, Japanese people are bow-legged, so they can't do those beautiful ballet movements that come so easily to white folks.

One other thing that jumps about Swan is that it's actually a very international manga. Early on in the story, Masumi and the other characters get a chance to attend the Bolshoi Ballet Academy. They head to Moscow, where they must compete on foreign soil against jealous Russian rivals. But the Russians aren't really bad guys; indeed, everyone acknowledges that Russian ballet is the best in the world. (Swan doesn't talk about politics, but it's hard to imagine an American comic or movie from the Cold War having such a positive view of Russian culture and never once reminding us that they're evil Communists.) Later, the characters travel all around the world and meet American, German, Cuban and British ballet dancers. All of them have different personalities and different looks -- it's impressive that Ariyoshi manages to make the Cuban guy look Cuban and the Russian guy look Russian (Sergeiev has an ever-so-slightly-bigger Caucasian nose) while still making them all look as gorgeously unreal as ice sculptures. Ballet is the characters' common language, and though they compete and suffer, they also become friends. But of course, even friends can fight one another. "Without rivals to stimulate you, you get complacent and stop growing," the ever-helpful Kusakabe says.

In short, Swan is a multicultural "be the best you can be" shonen competition manga in shojo drag. It's melodramatic and intense -- though never to the point of being cheesy and self-referential -- and it's fun. But the real joy of Swan is the artwork. Simply put, this is the greatest oldschool shojo manga art I've ever seen, better than the nicest-looking manga pages of Moto Hagio, Keiko Takemiya and Riyoko Ikeda. Of course the characters' faces are beautiful, in a '70s way, but Ariyoshi proves to be a master of drawing the human figure as well, and her gorgeous page designs are some of the loveliest fusions of shojo manga with Aestheticismand Art Nouveau. Even outside of the dance scenes, Ariyoshi uses inventive panel compositions, tapestries of plants and flowers and people and light. She's not just throwing some flowers and screentone in there and letting it all mix together; she designs her pages with skill, and (apart from one or two wonky hands) it's pretty clear she knows the fundamentals too. Like Sergeiev says to Masumi: "Your past training was based on poor technique. It's like a stack of boxes, piled too high and about to fall. It's the same for painters who keep painting without learning the basics of design." Sergeiev might just as easily have said mangaka instead of painters, and I'm sure Ariyoshi isn't a lazy mangaka. I pay her the greatest compliment when I say that I hope her fingers are bleeding drawing ballet manga this very moment.

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (21 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history