Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Oishinbo

by Jason Thompson,

Episode LXIX: Oishinbo

"He's like a gourmet demon! He sacrificed his whole family to his perverse obsession with food!"

—Oishinbo

America is one of the few countries that doesn't have a Ministry of Culture. Some would argue that organizations like the National Endowment for the Arts constitute government approval of certain cultural projects, and different citizens' groups and political organizations certainly push different ideas of what "American culture" is, but on the whole the US government stays out of the fray, at least officially. Contrarily, in Japan for example, certain traditional crafts and arts have the government's seal of approval, and some individuals are even designated Living National Treasures for their mastery of things like kabuki, noh, and traditional dollmaking. In America, a country with a shorter history and a more diverse population, the idea of the government singling out and promoting a certain "high" culture is more problematic (like, what would it be? Corn husk dolls? Scrapbooking? Bonnet-making?). On the other hand, American pop culture definitely doesn't need any help from the government, since in the form of movies, TV, video games and the ubiquity of the English language, it's famous just about everywhere.

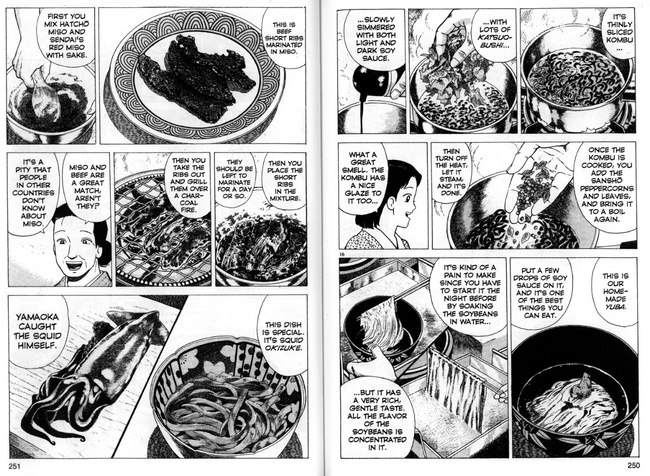

I got on this train of thought because of food; because of Oishinbo ("The Gourmet"), an awesome cooking manga which has been running continually since 1983 and which is available in seven translated volumes from Viz. Written by oldschool badass manga author Tetsu Kariya (who wrote Otoko Gumi, "Men's Gang," with Ryoichi Ikegami in the 1970s) and drawn by Akira Hanasaki, it's a foodie manga with just a dash of story, a plot as thin as passing a bit of kombu seaweed through some boiling water to give flavor to soup stock. Each chapter is full of info about food, and sometimes actual recipes, although more in terms of general tips than a step-by-step "use 2 tbsp of soy sauce, 1 tbsp of green onion," etc. (There's one or two mini-recipes here and there, but for detailed recipes, you'd really have to read Cooking Papa, Tochi Ueyama's untranslated manga which has been running since 1984 in a rival magazine.) Here you'll learn how to make dashi, how to cut sashimi and how to cook rice. From these basic tips, you might move on to tackling some of the really hard dishes shown in the story; and you'll certainly learn a lot about how food is grown and made, from the raw natural ingredients to the way it's processed, prepared and served. This might be TMI, but my mouth is watering as I write this. The power of cooking manga is that food is such a visual experience that looking at drawings of sumptuous food, or even reading descriptions of it, can actually make you hungry. And when I'm reading it on paper instead of digitally, I can eat as I read and I don't even care about spilling food on the pages.

Shiro Yamaoka is a food reporter for the Tozai News, who is hired by his boss to develop a project called the "Ultimate Menu." The Ultimate Menu will capture the essence of Japanese cuisine, and basically be a shining light for those of a discriminating palate for generations to come (I think…It's sort of unclear, but basically it's an excuse for the hero to travel around sampling different foods all the time). Yuko Kurita is Shiro's assistant, and like a patient housewife in a '50s sitcom (and—no spoiler—they get married later), she helps him out and cheerfully puts up with his crap, such as his tendency to spend his work time clipping his nails, sleeping at his desk or betting on horseraces. But like many manga heroes, when it comes to his area of expertise—food—Shiro morphs from a slacker to a genius. He's been cooking and studying food since he was a child, and he knows it all.

Like Shizuki in The Drops of God, Shiro's skill is partly inherited from his father, who's also a food expert, not to mention a famous and wealthy bizenware ceramicist. And this is where the tragedy starts. Shiro's father, Yuzan Kaibara, is one of those cruelly stern manga fathers who embodies the old Japanese saying that the four things to fear are jishin, kaminari, kaji, oyaji: earthquakes, lightning, fire and the old man. Whereas Shiro sort of tries not to push his food opinions on others, Kaibara is a perfectionist who uses his super-refined taste to show his superiority. When the food at a restaurant displeases him, he knocks the dishes off the table and humiliates the chefs, forcing them to make it again and again ("You call this suimono soup! It's undrinkable! The same goes for the fish niimono. The dashi used to simmer it is awful. Make it again!") The father and son haven't talked for years, and when Kaibara is hired to create the "Supreme Menu" for a rival newspaper, the gloves are off. "I was forced to sacrifice my youth for my father's love of food," Shiro growls. "But I could deal with that: it was my mother who had to make the greatest sacrifices for my father's gourmet extremes. She resigned herself to putting up with my father's relentless demands. She never had a moment's rest. KAIBARA IS THE MAN RESPONSIBLE FOR MY MOTHER'S DEATH!"

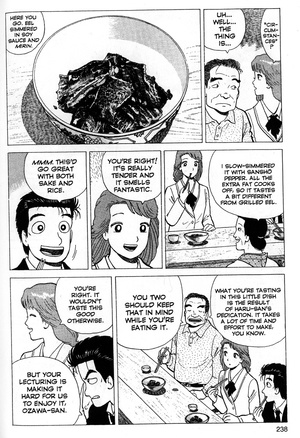

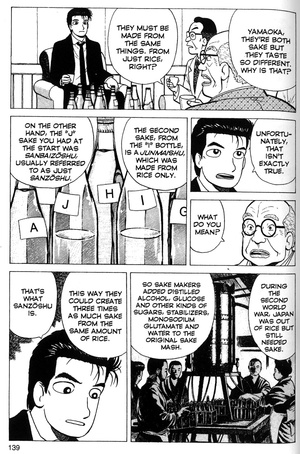

It's on!! Oishinbo follows Yamaoka, Kurita and occasionally the other newspaper staff around Japan as they go to different restaurants, taste different foods and sakes, and experience hundreds of food-related mini-adventures and side-quests. Along the way, they frequently run into Kaibara, and father and son get into bitter arguments about food, which Yamaoka sometimes loses. They visit restaurants and farms and fisheries; in one chapter, Yamaoka goes swimming in the sea in search of inspiration for a new way to serve seabream. They talk about rare ingredients and seasonings, but also about simple, natural food, such as the pleasure of serving something grown in your own graden. Yamaoka (and through him, Tetsu Kariya) is a natural foods advocate, and frequently criticizes the gross, artificial stuff which goes into food and liquor, particularly sake, most of which is pumped full of sugar, stabilizers and MSG, grain alcohol, charcoal and rice bran syrup. (In Japan, some of Oishinbo's claims about food additives, food labeling and GM crops have resulted in controversy and criticism from the Japanese food industry.) Yamaoka is a fan of slow food and artisinal (that's such an overused buzzword, but there's no other way to say it) foodmaking techniques; he even praises handmade chopsticks. But the chef's intentions are also important. "The most important thing in raising food to the level of an art form is to touch the hearts of those who eat it! An the only thing that can touch a person's heart is another person's heart—you can't fake it by relying on good ingredients and techniques!"

While it's not full of actual recipes, Oishinbo is a great manga to give to someone who cooks; it's full of ideas and info about food. While some of the ingredients may be hard to find outside of Japan, at least it's easier for a foreigner than following in the footsteps of Fumi Yoshinaga's Not Love But Delicious Foods!, her manga restaurant guide to restaurants in Tokyo. A typical Viz volume has more than 10 pages of cultural footnotes. Of course, even an information-packed manga like Oishinbo needs some character or conflict to make it interesting; otherwise it would just be an info dump. Although this isn't an outright tournament manga like Iron Wok Jan, Yamaoka shows his mastery of food through expertise and good taste; food is an art form, and Yamaoka is an art critic. Many storylines involve Yamaoka schooling somebody who's got messed-up opinions about food, and turning them around to his (proper) way of thinking.

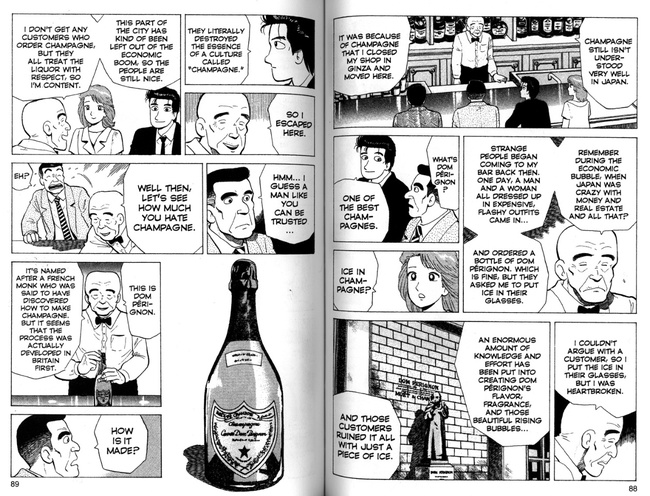

One recurring conflict of taste is between Yamaoka and "Westernized" Japanese people who have developed a negative attitude towards Japanese food and, more generally, Japanese culture. In one story, a businessman's daughter comes back from living in France and doesn't want to use chopsticks anymore ("They're backwards and uncivilized. It's just so unseemly when people eat with them!") A writer who's lived overseas loves Western liquor and hates sake. ("Sake is just undrinkable! It's got no distinct fragrance, it's far too sweet, the palate too heavy, and generally it's just lacking in class! You'd probably end up with something like this if just mixed together some water, rubbing alcohol, and sugar!") A critic who's lived abroad hates sashimi. ("Can you call that a 'dish'? All you've done is slice the fish and put it on a plate!"). Again and again, Yamaoka proudly defends Japanese food from the foreign imperialistic diet of hamburgers and spaghetti, accusing the Westernized returnees of having a cultural inferiority complex. ("Yeah, well, that kind of bias is typical from someone who worships foreign things and blindly adores anything from the West!") Defending Japan's culinary traditions, he also stands up for foods which some Westerners find shocking, such as fish and squid that is cut up and served alive. ("It sounds cruel, but it's so good that you won't have any qualms about it once you eat it.") In another story, he speaks out in favor of whaling.

This pride in culinary differences may be surprising to English readers, but to Kariya's credit, Oishinbo is nationalistic but never racist. In the chopsticks storyline, it's a French woman who speaks up for Japanese culture to the self-hating Japanese girl ("There's something in every country's culture to take pride in. Anybody who claims that something is uncivilized just because it's different from the standards of their own culture lacks flexibility and understanding. That is what I think you can truly call uncivilized.") In another story, an American sushi chef goes to Japan to train, and manages to defeat a Japanese chef in a knife-cutting contest, because the American is sincere and hard-working rather than flashy and showy. (Of course, the American guy is drawn with a huge nose and a bouffant of blonde hair, but….) In another specifically anti-racist story, Kariya criticizes Japanese people who use old-fashioned racist terms for Chinese and other Asians. And although the translated volumes focus on Japanese food, the untranslated volumes include tons of information on French, Italian and other cuisines. According to the author's notes, Kariya has been living in Sydney, Australia since 1988, so he's obviously got awareness of other cultures; and Oishinbo shows it. And Kariya/Yamaoka doesn't pull punches when Japanese food is bad, such as his six-chapter exposé of the sake industry.

Rather than publish all 100+ volumes of Oishinbo from beginning to end the way they were originally published in Japan, Viz chose to translate Oishinbo: a la Carte, a series of Japanese "perfect collection"-style compilations where selected stories are gathered together by food type. Some reviewers complained about publishing the series out of chronological order, with a typical complaint on goodreads.com being "they ruined an amazingly entertaining series... it's extra annoying because the whole series is ultimately about the essence of being Japanese, and Viz completely sh*t on the essence of this series with this presentation." Except that THE A LA CARTE EDITION WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED THE SAME WAY IN JAPAN, STUPID! Although Viz did decide to publish the Japanese-themed volumes of a la Carte first and not publish the volumes on yoshoku (Western dishes), I don't think you can blame 'em; just as most fans read manga for Japanese cultural stuff, most foodies probably read Oishinbo for Japanese food first and Western food second. (The seven volumes released by Viz are Japanese Cuisine; Sake; Fish, Sushi and Sashimi; Vegetables; The Joy of Rice; and Izakaya Pub Food.) Since Oishinbo: a la Carte stories are published out of chronological order, it's true that there are some confusing story gaps, such as the hero and heroine getting married offscreen between chapters. But let's face it, Oishinbo is not really a continuity-based series. Like Golgo 13, there's not a tremendous amount of continuity between chapters, so you can read it out of order without losing too much. You come here for the food, not the service.

Like a classic TV program that's been on the air for nearly 30 years, Oishinbo is repetitive but it works: it has delicious artwork, father-son rivalry, moments of comedy and lots of interesting food factoids. I've always wondered why "information-rich" manga like Oishinbo aren't more popular in the U.S., and that the infomanga style isn't more popular among YA manga in Japan either (take Mixed Vegetables for example—both of the main characters are chefs, but I didn't learn a thing about cooking from that dumb series.). Maybe there's too much text sometimes when they're talking about food, or maybe it's the old-fashioned character artwork which turns away readers. (Would Oishinbo be more popular today if you moe-d up all its character designs? Would The Drops of God be less popular if the hero looked like the dude in Oishinbo instead of like Light Yagami? I think I answered my own question.) Perhaps an oldschool, crusty seinen manga like Oishinbo can never be popular in the American manga market, but trying to market it to foodies and non-manga-readers has other problems; the New Yorker reviewed and praised Oishinbo but, like my parents, were bewildered that it reads right to left. I could write more about Oishinbo, but by now, I'm starving. Oishinbo: read it. Eat its recipes. Ask Viz to translate more volumes. And if you disagree with Kariya about whaling, or chopsticks, or whether white wine goes with seafood better than sake, the best solution is to write your own manga.

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (15 posts) |