Interview: The Secrets of Deca-dence

by Lynzee Loveridge & Kim Morrissy,Last time we interviewed the Deca-Dence team, we had no inkling of the surprises the series had in store. Director Yuzuru Tachikawa is back for round 2, along with Cyborg designer Kiyotaka Oshiyama and Deca-Dence designer Hiromatsu Shu. Read on to find out more about the design philosophies that shaped this very unique anime.

Warning: This interview contains spoilers for episode 2 and beyond.

(For Yuzuru Tachikawa) The world of Deca-Dence and Solid Quake corporation look very different. What are the staff hoping to communicate through these stylistic differences?

My first priority was to ensure that the two protagonists stand against two very different backdrops. I wanted to depict a story where the two influence each other, live, and change. I also wanted to challenge myself by creating something that flips between two screens that are so detached from each other that you would think that they belong to different works. This was necessary so that the rulers of the world that commodifies those “humans” as products have their looks drastically different from the humans. This also encompasses the issue of broadcasting ethics.

In the current world of Deca-Dence, most of humanity is gone and the planet's resources have been destroyed. A corporation has purchased humanity and controls the robot players. Are there any themes in Deca-Dence that you hope viewers consider?

Robots that can be active for several hundred years if they undergo maintenance, and humans who are treated as commodities in an entertainment complex… This anime depicts what it means to “live” from those two drastically different viewpoints.

The robots like Kaburagi have a full range of emotions, but… they're very cute. Was this purposeful to entice viewers to cheer for the robot players despite the fact that they are not human?

The fact that his society commodifies humans would make them unlikable from the audience's perspective, so I took care to ensure that their designs would be pleasing. It would please me if you find them cute.

What made you decide to reveal the setting of the anime in episode 2, instead of episode 1 or towards the end of the anime?

The original plan was to reveal it in episode 4, around when Kaburagi tries to stop Natsume from participating in the battle. But it was difficult to understand Kaburagi's emotions while keeping the nature of the setting under wraps, and it was hard to depict the drama we were seeking. Revealing it in episode 2 would overturn the fundamental expectations for the structure set up in episode 1, so I did have some uncertainties about whether it would be well-received by the audience.

(For Kiyotaka Oshiyama) What were the circumstances behind you handling the cyborg designs?

I first met Tachikawa when I was directing Flip Flappers and he worked on the 6th episode's storyboards. Through that connection, I worked on Mob Psycho 100, which Tachikawa directed. I didn't appear in the credits, but I handled some of the background art concept designs for the enemy hideout, and some other things.

From there, I got asked to work on the cyborg designs for this anime.

When you design characters or creatures, do you consciously attempt to make them look different from anything you've drawn before?

Whenever I think of designs for an original work, there's a feeling of discovery of something I've never seen before, and I value that greatly. Doing it that way will ensure that both the audience and the artist will be compelled by the work when they face it, but the biggest thing for me is my desire not to draw the same thing over and over. If, for instance, I set out to draw something completely differently from how I did it before, my quirks as an artist would leak out, so I've been doing my best to approach this work with a neutral feeling, to create the design that best suits it. Also, I once heard that the Bones president Masahiko Minami said, “Don't worry. Whatever Oshiyama draws will have Oshiyama's flair.”

What sort of instructions did you receive from the director?

The thing that left an impression on me was when he said at our first meeting, “The cyborgs don't understand death.”

This is why Deca-Dence is a game that sells death, but I think that when it was conceived, the cyborgs felt less fear than the humans did, comparatively. Director Tachikawa also told me to make the designs cute so that people can form an attachment to them, so through the colors and shape I created a design that conveys their lack of fear towards death, their large eyes and short limbs, their baby-like cuteness, and their detachment from reality.

How much did you consider the post-apocalyptic setting when drawing the designs?

The cyborgs may not possess the concept of death, but their thoughts are otherwise very much like humans. One of my favorite picture books is The Cat Who Lived One Million Times, which is a story about an immortal cat who learns about love and dies for the first time. I think that this story had a happy ending, but as for the cyborgs who don't love and are never allowed to die in an endlessly resetting game, perhaps you could say that their lives have a bad ending according to our values system.

A number of characters in the anime have both a human and a cyborg appearance. How did you try to convey a character's personality through their cyborg design?

At the stage when I designed the cyborgs, the only ones who had a human concept design were Kaburagi and Minato. Kaburagi is an armor mechanic, so I gave his face a welding mask motif. I also added the high-visibility colors of a construction site worker's outfit to him to express his gruff and taciturn masculinity as he goes about his job. Because of director Tachikawa's directions, I gave him spiky hair that resembles his human hair and a backpack rocket that is reminiscent of the days he was trying to act cool.

Minato has a newer body than Kaburagi, so I gave him a sharp and streamlined form. I drew him so that he had supple limbs, but director Tachikawa advised me to give him pronounced joints in order to convey his stickler-in-the-mud personality. Each character also has a theme color so that their design does not diverge from their human form.

(For Hiromatsu Shu) The Deca-Dence exterior is very detailed. How many details were added over time and how long did it take to finalize the design?

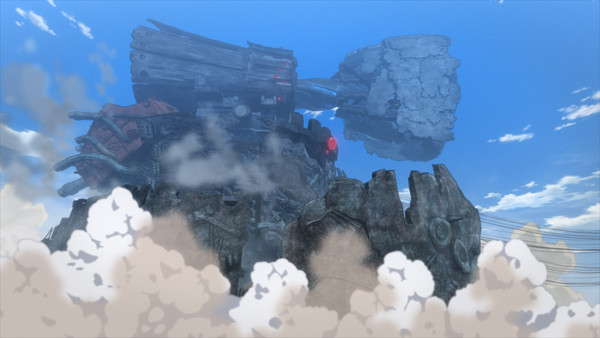

I forgot how many details there are, but I tried to add more details that fit a city more than a castle or a fortress (laughs). I had the sense that it's as if the entirety of Tokyo was crammed into a vertical structure. On a visual level, adding more details would also convey the scale. Also, I would add details to convey the functions and staging that the director Tachikawa-san wanted to put in. From the initial rough stage, we had the concept of “the mouth of a giant face,” and after later conversations, we made it the gate where attacks come out of. Also, because of that function, we added a descending runway which appears when the front shields activate. All of this work took around half a year.

How much did you keep in mind the interior of the Deca-Dence as you were designing the exterior?

In the reference drawings I received at the early stage of the design, the interior functions and vertical structure were already quite fleshed out. I thought that the vertical part only has an influence on the appearance of the exterior, so I didn't intend to commit the interior to mind at all (laughs).

Then, as the work was proceeding and it became time for me to think about the transforming mechanisms, I got stuck on how to make the gun barrel stow away. I had no choice but to think about the interior. I looked back on the initial reference drawings, and the interior divisions were drawn on quite a level surface. When I translated that into a three-dimensional object, everything besides the shell was like an internal organ, which meant that there was no place like a bone or a muscle to serve as a stowing place. By re-evaluating the interior, I was able to resolve the problem of how it reflected the exterior appearance. It turned out to be impossible to get away without looking at it.

How did you try to convey the feeling of dystopia through the design?

For me, dystopia isn't just about lifeless colors or a standard of living that shows no development. The Tankers have liveliness and are allowed (albeit limited) freedom and individuality. From the human perspective, their world has a post-apocalyptic atmosphere, through which the “Deca-Dence” of the world is portrayed.

In comparison, the world of the cyborgs, who say things like, “The world must be rid of bugs.” is closer to the 1984-style of dystopia. For the cyborgs, the world of “Deca-Dence” is a world they escape from their reality to as a form of entertainment. That, too, is close to the dystopia of Brave New World. When the privileged class rules in perpetuity without even touching any other world, that, to me, is dystopia. I wanted to convey such things through the Deca-Dence Core, the surrealist mechanisms (the muscle light fibers, the muscle tissue section in the gun breeches, etc.), and the gap between the control tower and the tank city

What are your biggest inspirations as an artist?

I take a lot of inspiration from normal everyday life. I spend a set amount of time drawing every day, so when I get out and watch a movie, play a game, read a book, or take a trip, it's relatively easy for me to soak in inspiration during that time spent recharging. Art is a form of expression as well as the result of expression, so I've got to make sure I'm not lacking in both practice and in my critical thinking skills. In that respect, inspiration is not a flash of brilliant insight but the greatest common denominator between what you can express and what you want to express.

What were your thoughts when you became aware of the science fiction setting? How much did your understanding of the story shape your design?

First of all, when I realized that it wasn't hard sci-fi but that it has an air of playfulness to it, I was relieved. When the story was explained to me it seemed like it had more than enough novel ideas, even just from the requests regarding the designs. Some of the expressions that I can remember being bandied about at the time are “3km tall,” actually “a game with a real set like The Truman Show,” and “The weapons are punches,” which made it all hard to visualize in my head. So whenever I had a question about the story, Tachikawa-san would explain it all for me.

As a result, I think I was able to make a design that served a purpose in the story. Some of the angles and visuals that I first thought of through the design ended up being depicted in some of the actual scenes. I'm glad that I was able to expand the world of Deca-Dence. The designs of the core, the demolished site, and the final form were added later, so I would have liked to put in more common elements like codes and symbols… That's my little regret. I think about it whenever I watch the broadcast (laughs). Although I would have liked to learn more about the story, I'll take what I've learned to my next job.

discuss this in the forum (2 posts) |