Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Manga and Mega Comics

by Jason Thompson,

Episode LXXI: Manga and Mega Comics

There's a thin line between self-publishing and vanity publishing. In the old days before digital publishing and POD (print on demand), to get a book published, you needed to convince an editor at a major publishing house who had the money and connections to get it done. If that failed, your only real option was to go to a vanity publisher, who would handle the editing, printing and distribution…for a price. Basically, you were paying someone to publish your book for you, but the very words "vanity publisher" carried a stink of desperation, since most vanity publishers would publish any old crappy book as long as you had money. But really, the only distinction between vanity publishing and real publishing is whether people buy it.

In comics, on the other hand, self-publishing has always been a little more accepted. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles started out as a self-published book, and it was so successful that it led to a boom in black-and-white comics which indirectly led to the creation of the first American manga publishers, Studio Proteus and VIZ, in 1987. Before that, barely any manga had been published: the major companies like Marvel and DC wouldn't touch it, the small American comic publishers who did B&W books didn't know about it (and were mostly trying to self-publish their own stuff anyway), and for the Japanese manga publishers—who at the time were making major bank in Japan—the American market seemed so rinky-dink and tiny that breaking into it wasn't even a priority. But a few mangaka in Japan were interested in the American market, even if their publishers weren't. They threw money into nicely produced, before-their-time English-language graphic novels which usually crashed and burned, like Gō Nagai's 1986 edition of Devilman and Takao Saitō/LEED Publishing's Golgo 13 books (released to tie in with the NES game). Or one of the earliest, the anthology book simply titled Manga, the most un-googleable title ever, from a company called Metro Scope.

Manga is an 88-page magazine probably released sometime between 1980 and 1982. (There's no date on it, and no one's exactly sure.) With its anthology format, its airbrushed logo and its robot girl on the cover, it looks a lot like Heavy Metal—not a bad way to sell it, since most of the few manga printed in English in the early '80s were short stories in adult comic magazines like Star Reach, Heavy Metal and Marvel's Epic Illustrated. Around this time, Blade Runner was coming out, Frank Miller was drawing ninjas in Daredevil, and Americans were just starting to get obsessed with Japanese pop culture. Could Manga teach the curious Westerner about this mystical land of Oriental Adventures, samurai and gynoids? Why yes, it could! The back cover editorial by Tadashi Ookawara, the only explanation of this strange object, reads:

"Perhaps the most widely read publication in Japan is the 'manga' or comic book. Over seventy-seven million comic books are sold monthly throughout the country. Unfortunately, due to differences in languages, customs and editorial practices virtually no mangas have been translated into English and introduced overseas…Our purpose in publishing Manga is to give the non-Japanese reading public a visual taste of Japan and the creative talents that exist there. Nothing would give us greater pleasure, however, if in doing so we are able to boost the cultural understanding in the west about Japan."

It's an editorial which appeals to the reader's sophistication, and indeed, Manga is a classy book. It's adult but not too adult: Hajime Sorayama, an artist who sometimes seems like he keeps a speculum on his drawing table, keeps it classy on the cover illustration with just the littlest arrow pointing to the robot's crotch. Breasts are bared, samurai's bodies explode in showers of black inky blood in Hiroshi Hirata's story, but it doesn't dwell on slime and gore and sex in a conscious "Up yours, Comics Code!" kind of way, like many of the American underground comics.

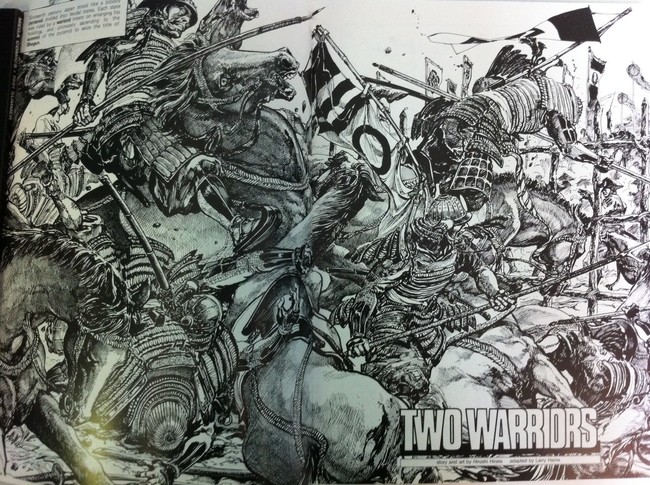

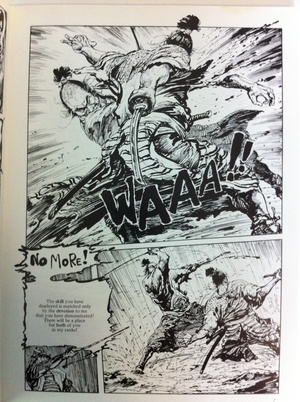

Except for two pages of funny-animal gag cartoons by Masayuki Wako, all the stories in Manga are either science fiction or are set in historical Japan. The first and longest story is by Hiroshi Hirata, the most badass and authentic of all historical manga artists. Hirata's vigorous, brushy, heavily detailed art style is vaguely reminiscent of Goseki Kojima, but his ultra-precise anatomy is more Western-looking, and Hirata's samurai manga are so mean and rugged they make Lone Wolf and Cub look like Red Hot Chili Samurai. Imagine Lone Wolf without Daigoro or any humor, and with no guarantee that the main character will survive from chapter to chapter, and YOU're sort of getting it. Dark Horse published three of the five volumes of his epic Satsuma Gishiden ,but his involvement with Manga shows that he's been interested in the American market for a long time. (He also collaborated with a Western writer, Sharman Divono, in the 1987 one-shot Samurai: Son of Death, a book whose failure is entirely due to DiVono attempting to cram about 200 pages of story into 48 pages.) His story "Two Warriors" is about two friends, Kichibei and Jubei, bald men with hard faces, who both want to become samurai in the service of the Great Lord Tadanaga. Tadanaga tells them to fight one another to the Death and the one who wins will be admitted into his ranks. Kichibei hesitates ever so slightly, allowing his friend to win, and loses the battle as well as an arm. Tadanaga is so impressed by their willingness to kill each other that he spares Kichibei's life and allows both men to enter his service, but beneath their superficial friendship, Jubei grows ashamed and resentful because deep down he knows Kichibei threw the match. This is a classic samurai story of cruelty and honor carried to insane extremes, with lines like "Friendship is alien to the warrior's creed! There is honor only in victory or Death! Friendship is just another adversary!" Yeah, take THAT, Shonen Jump! This is definitely the best story in Manga, both due to Hirata's talent and the fact that it's 20 pages long, a reasonably spacious page count for a story, whereas most of the Manga stories are much shorter and read like Western comics due to their excessive narration.

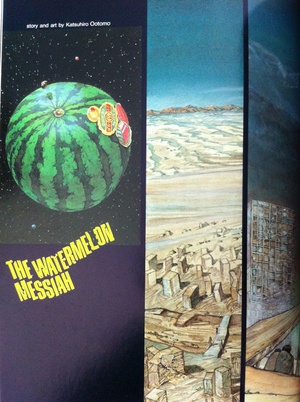

Take Yukinobu Hoshino's "The Mask of the Red Dwarf Star," a 10-page story about Roscoe, a beardy space criminal. While floating out in deep space as a result of a job gone bad, he's picked up by a luxury liner spaceship carrying crass old rich people in suspended animation, so their remaining years of life can be stretched out as they wander the galaxy seeing the sights. The story is full of jaunty first-person narration. ("Though I'm not exactly an Einstein when it comes to scientific things, I have a veritable sixth sense for danger…which is exactly what's kept me alive this long.") Things go bad in the spaceship, just like in the Edgar Allen Poe story it's based on, and Roscoe manages to get out of danger and get the girl, albeit sorta nonconsensually. With its high detail and chiseled character designs, Hoshino's artwork is also rather Western-looking, which is one reason VIZ chose to publish several collections of his science fiction stories, Saber Tiger and 2001 Nights, in the late '80s and early '90s. Dark Horse also published his adaptation of James P. Hogan's The Two Faces of Tomorrow. Hoshino's long-form work is very thoughtful hard sci-fi, but there's only so much you can do in 10 pages, and so "Mask of the Red Dwarf Star" is a sci-fi story where it's all about visuals and one cool (or in this case, not that cool) idea; there's no real room for character or emotion. I also prefer Hoshino's B&W work to his color work. Katsuhiro Ōtomo (yes!!) also has a story in Manga, and it's also a visual thing. In the wordless full-color "The Watermelon Messiah" Earth has become a desert wasteland, until a giant space watermelon crashes down from the heavens, and the starving people swarm on it like ants. It's a beautiful little Otomo apocalypse. Noriyoshi Olai contributes some color paintings of Star Wars artwork and sci-fi pinups of women in jeweled loincloths.

As you probably noticed, the comics in Manga are generally very Western-looking. Presumably in their desire to appeal to Americans, the editors picked a very specific group of artists: as other reviewers of Manga have pointed out, there's no hyperactive shonen manga, no anime-style big-eyed stuff in the Hideo Azuma vein, no Shōjo Manga, just seinen tales of manly men in manly scenarios. The closest thing to a shojo story, although it's still several degrees removed, is probably "Midsummer Night's Dream," a collaboration between American underground comic artist Lee Marrs and underground mangaka/musician Keizo Miyanishi, both of whom are still working in comics. Miyanishi's work appeared in AX volume 1, exquisite artwork in a decadent style a bit like Kazuichi Hanawa or Suehiro Mauro. Loosely inspired by a story from The Tale of Genji, it's an erotic fairytale in which Genji, the main character of that work, is traveling through the woods and admires a yugao flower. When he turns around, he finds that the flower has transformed into a strange, bewitching woman who resembles his mother, and then things get sexy. Like many of the stories in Manga, it'd be better with less text: some lines are just redundant ("Hikaru moved like a man under a spell. The lady's beauty was riveting. Her tones carried the echoes of trust, openness. He drank in every detail of her loveliness…") but others are really questionable ("This vision had unlocked his heart, opened the door of his soul to the wonder of sharing").

Still, even if it tries to cram too much subtext and backstory into 8 pages, it's a good story. It's also drawn in a really unique style, unlike some of the creators in Manga who mimic the look of American comics as much as possible, notably Noboru Miyama's "The Great Ten," a 12-pager about spaceship pilots who race through a deadly maze, and Masaichi Mukaide's "The Promise," a 10-pager about a samurai who meets a yuki-onna on a snowy night. Of course, who am I to tell Japanese creators they can't imitate American comic artists if they want to? I don't want Japanese artists telling me I ought to imitate Jack Kirby. But just like manga readers in Japan generally aren't looking for Westerners who try to draw exactly like manga—the Morning International Manga Contest changed their name to the Morning International Comic Contest because they were sick of getting entries that tried to look 'manga-style'—I read manga primarily to see new styles instead of the same stuff I can get back home. But Manga isn't solely American-focused: Yousuke Tamori's three-page sci-fi story, "Down Time," is drawn very much in the style of Moebius. There's only one more story to mention, Youki Fukuyama's "Schizophrenia," a simple, creepy little sci-fi comedy about a man who builds a time machine to go back in time and escape his boredom. Fukuyama's art reminds me a bit of Naoki Urasawa's.

Coming out just at the time when small-press comics were becoming a viable commercial market in the US, Manga must have been a fun book to work on. It's a real international collaboration: in addition to Lee Marrs, a couple of other American comic creators worked on the English adaptations of the stories, including G.I. Joe creator Larry Hama (!). The person who put all this together is probably Consulting Editor Mike Friedrich, who had previously published some science fiction and fantasy manga in his magazine Star*Reach before working on Manga. The translations are good and the whole thing is a very nice package, but some curious omissions, like the lack of a publication date or a price on the cover, make it a little more believable that Manga sank from sight so fast and never had a second issue. (Although to be fair, there's no indication that it was intended as more than a standalone. There's not even a US address to send letters to.) Who bought this? Did it get distributed in comic stores? Did anyone review it, and what did they think? I'd like to say that it was ahead of its time, but since it's done so much in imitation of Heavy Metal, I can't really say that. Was it intended to make money and maybe lead to more Mangas, or more as a portfolio piece for the artists who contributed to it?

The next book I'm reviewing this week, Mega Comics, was definitely supposed to make money. Mega Comics came out in 1991, 10 years after Manga, and in that time the American manga market had completely changed. For one thing, it existed. The manga boom is still ten years off, but companies like Viz and Studio Proteus were publishing a small but steady stream of manga (mostly in the floppy comics format rather than magazines like Manga or graphic novels like Devilman and Golgo 13), and translated anime was available in the direct-to-video American market as well.

At last, the American market was big enough for Japanese publishers to want a piece of the action, and instead of focusing on 'high' culture like samurai, they could focus on pop culture, like anime. The anime studio Gainax, at the time best known for The Wings of Honneamise and Nadia (this was even before Otaku no Video), were interested in cultivating their US audience. In summer 1991 they released Mega Comics, a 122-page partially-color, partially-B&W book. The message of Mega Comics was, Hey fanboys! Get your manga directly from us! This is authentic comics…I mean manga!

Or, as the back cover put it:

Mega Comics has the worst translations I've read in nearly 20 years of reading manga, except possibly for NTT Solmare's cellphone manga. Unlike Manga, it's clear there wasn't much proofreading; this is what can go wrong when a book is produced entirely by non-native speakers. Or almost entirely; the credits list the "Translater" as Katsuji Yatsusige, but I'd like to ask "Assistant Translater Creig York" a few questions. But anyway, some fans like super-literal translations, right? Mega Comics ("Comic, Graphic Novel, Illustration & Anime Information") was going to be part anime magazine (like the already-existing Protoculture Addicts and Animag) and part manga magazine, like the still-a-few-years-off Manga Vizion and Pulp and Shonen Jump. The first (and only) issue included 12 B&W and color pages of info, screenshots and design art from the then-new anime series Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water (a Gainax series, naturally.)

There's also a few manga. "Night Search" by Akihiro Itō is a 14-page police drama about a cop, Louie, looking for the perp who caused the Death of his wife and unborn daughter. Full of guilt over their Death, the brooding, middle-aged Louie gets a new partner, a cute girl, who guides him on his quest for revenge and redemption. Ito, the gun-happy creator of Geobreeders and Wilderness, tries to mix cute and serious, and the art is a little crude when he's not drawing the girl. The translation has rough spots, but what's really awkward is that the word balloons all contain both Japanese and English text: an attempt to resell Mega Comics in the Japanese market, perhaps? It's the same in Mamoru Ikeuchi's "The Passenger," the first 8 pages of an apparently never-finished cyberpunk story drawn with competent but stiff full-color painted artwork that looks like illustrations from the Shadowrun RPG. Basically: a woman goes to Shinjuku to buy an alien fetus from an alien fixer, and along the way she gets mugged and has to shoot some people. ("The feel of cold steel. I don't stop to think…Don't stop! My instincts shout. Finish them!") It ends "To Be Continued…" but, nope. More interesting than both these manga is the next section, "Mega-Talks from Manga Writers," which is a series of two-page spreads introducing different manga artists and showing their art. Would Mega Comics have published some of these artists if it had continued? The portfolios include two artists who later got published in English, Hitoshi Okuda (No Need for Tenchi!) and Hiroyuki Utatane (Seraphic Feather and various adult manga). Apart from Motoo Koyama, I'm not familiar with the other artists, and I wonder which one of them became professionals and which ones were just dojinshi artists who knew people at Gainax. Whatever happened to Ayumi Konomichi? ("She is a young and energetic comic writer. Characteristic of her work is a sense of tender femininity and the sharpness of her original observations. Our only complaint is that she doesn't write longer works!") Or Marino Nishizaki? ("He's been writing comics for ten years, but his published work consists of only three fanzines and one prozine. Because he's very particular about his work, his output is low.")

But the biggest story in Mega Comics, filling 64 pages, is Ikuto Yamashita's "Attesa." "Attesa" is a prequel to Dark Whisper, one of Yamashita's successful commercial manga, set sometime in the 21st century after a strange event in which most of the population of America simply vanished. There was also a nuclear war, and civilization is rising from the ashes of these two events. Basically, it's a 'mysterious lost super-civilization' story in which the United States of America is the lost super-civilization. The main characters are Enora, a scruffy 30-year-old salvage boat pilot, and Coyomi, a little girl he finds in a tank he hauls up from the bottom of the ocean off Puerto Rico. Turns out that Coyomi is an eternally prepubescent, apparently genetically modified CIA agent, one of the last survivors of America, although she won't or can't explain exactly what happened. "I am the eyes and ears of the United States," she says. When some more Americans are awakened and try to activate secret high-tech weapons, Enora and Coyomi and the U.N.F.C.D. (United Nations Force of Cataclysm Detachment) must try to stop them from upsetting the balance of world power.

It seems like a pretty interesting manga in the Eden style, there's some high seas action, and the art is nice: Adam Warren is a fan of Yamashita's mecha designs. "Attesa" is also published right to left, which made me realize something unusual about "Night Search," "The Passenger" and all of Manga: they're all drawn left to right, meaning they were original works drawn for American publication! "Attesa" is the only one actually made for the Japanese market, and rather than 'flip' it like companies used to do back then, they published it in the original format presumably to respect the artist's wishes. Unfortunately, it's almost unreadable in the way that it's presented. Instead of translating the text INSIDE the word balloons, even Japanese-and-English-together like "Night Search" and "The Passenger," they used only the Japanese text but included English translations in the margin. This is already hard to read, not to mention that half of the translations are misnumbered, missing or on the wrong page. Printing it right to left was fine of course, but with the awful translation format, reading "Attesa" was so frustrating my eyeballs wanted to jump out of my head and run away, with my optic nerves trailing behind them like leashes trailing after two little dogs.

The awkwardly literal formatting and translation of Mega Comics, and the "join our religious cult" sounding cover text, reflects a trend in manga which had begun in 1991 and continues today: manga readers were now willing to pay more for authenticity, or the illusion of authenticity. However, they apparently weren't willing to pay $17 for 122 pages of badly translated manga, or to pay $25 for an annual membership in Gainax's "General Products Club," a vague-sounding mail-order thing advertised in a big 3-page ad in the magazine. (You don't even get a full year's membership starting from when you order!! If you join in November, your $25 membership only lasts until December 31st before you have to renew!) Gainax never published another issue of Mega Comics and from that point on, they left the sales & marketing of their stuff to the American licensors.

Carl Gustav Horn, the wise and always impeccably clothed Dark Horse Manga editor, loaned me his copies of Mega Comics and Manga to write this article, and as a major Gainax fan, Mega Comics is one of the prizes of his collection. Although they're very different works, they have in common that were published in Japan and thrown onto the American market in an attempt to appeal to what someone thought American manga fans would like at the time. They failed, but other companies succeeded. Since digital publishing makes it so easy, there will probably be more and more manga produced directly in Japan without American intermediaries. jmanga.com was initiated in Japan without the involvement of American manga publishers, for instance, and for a less corporate example, artists like Hitoshi Ariga and Yoshitoshi ABe are now able to publish their works directly in English on the iPhone, iPad and Kindle, which is awesome. Some people would say there's not much need for traditional publisher anymore. But even today, getting published by a "real" publisher gives you some distribution and marketing connections and a certain sense of clout. For instance, in the 2002-2007 manga boom, some manga companies knowingly published unprofitable books just to flatter the vanity of mangaka who were bestsellers in Japan and thought it would be cool to be published in America. A lot of manga published in America is vanity publishing.

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (6 posts) |