Interview: Steve Alpert, The Westerner at Ghibli

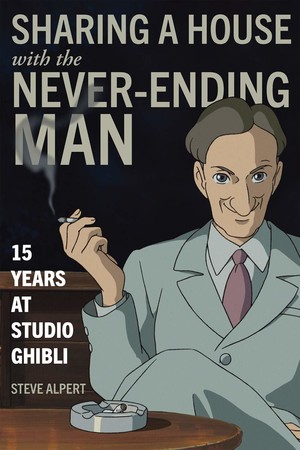

by Andrew Osmond,Studio Ghibli fans will be devouring Steve Alpert's book Sharing a House With the Never-Ending Man, written by the American who was a member of Ghibli in its greatest years. Alpert discloses a fantastic number of secrets about the turbulent time when Ghibli sold its films to Disney, giving new perspectives on Hayao Miyazaki, Toshio Suzuki and Ghibli's overbearing owner Yasuyoshi Tokuma.

In this interview, Alpert talks about Ghibli's perilous business plan, clears up that story about giving a sword to Harvey Weinstein, and recalls when he made Hayao Miyazaki cry.

In your book, you describe your experiences in vivid detail to put the reader into the scene, from a Christmas Eve at a Paris family home together with Miyazaki and Suzuki, to the extraordinary pomp of Yasuyoshi Tokuma's memorial service. Are you just blessed with a good memory, or did you keep a diary at the time?

In your book, you describe your experiences in vivid detail to put the reader into the scene, from a Christmas Eve at a Paris family home together with Miyazaki and Suzuki, to the extraordinary pomp of Yasuyoshi Tokuma's memorial service. Are you just blessed with a good memory, or did you keep a diary at the time?

I used to have a great memory, but now that I am older, not so good. Living in a foreign country for 30 years with friends and relatives far away, you write long letters. I did anyway, even in the age of e-mail and Twitter. The digital age allows them to be stored and referenced, and later mined. So maybe a kind of diary, but sporadic and unsystematic.

You write about your friendship with Toshio Suzuki and how he is instantly recognized in Japan. To foreigners, he can just seem a very courteous gentleman, but I wondered what kind of public image he has cultivated in Japan – how Japanese people see him. (I've always been intrigued by how Suzuki started as a journalist, covering scandals and biker gangs, including working on the Asahi Geino magazine that you describe vividly in the book.)

This is a topic that deserves volumes. There should be books about him for the different phases of his career. His Ghibli days of course. His stories about his days in publishing are amazing. He's that rare combination of creative guy and solid businessman. And he's always been a very good public speaker. I'm not entirely sure about courteous gentleman. He has a booming (orator's) voice and he's not shy about saying exactly what he thinks.

I'm not the best qualified person to say how the Japanese people see him. I think Suzuki-san has always been something of an iconoclast. He does the unexpected. He's broad-minded and gets along with a lot of very different types of people. He doesn't dress like your average Japanese person. He has a way of ferreting out the hidden details of a story, which I guess might be the definition of a good journalist.

You explain how Suzuki worked hard to publicize Princess Mononoke to Japanese people as “the film Disney had bought” – even extending to you being forced into an appearance on late-night Japanese TV! Of course, Princess Mononoke ended up being a record-breaking blockbuster hit in Japan. If the Ghibli-Disney deal hadn't happened, Princess Mononoke would surely have still been a hit in Japan, but do you think it might have earned far less?

I learned from Suzuki-san that when you're promoting a film everything is important. Whatever you can do, you do. Ghibli was built to make feature-length theatrical animation. The filmmakers run the studio, so they make the films they think should be made the way they want to make them. How popular the film might be and what kind of money it will make doesn't influence the making of the film as it might in a large commercial studio. They decide to make the film first and figure out how to promote it after.

Ghibli's business structure from the beginning was to live or die based on the success of the Japanese theatrical release of each film. Succeed with Film A and have the money to go on to make Film B. If the one film they made every two years or so failed, then the studio would (might) go down.

That was the way Hayao Miyazaki liked it. He often said that you do your very best work when you can truly feel the consequences of failure. That goes for the animators and the people running the business side of things.

I'm not sure it's possible to say what portion of the film's commercial success came from the association with Disney. Suzuki-san had a lot of things in his promotional bag of tricks. He knew the Japanese theatrical market better and in finer detail than anyone. He spent a lot of time thinking about how Japanese people behave and how best to optimize his promotion of the film.

Isn't your question a little like asking what is the sound of one hand clapping? In a different kind of company, I suppose I would have been expected to be able to answer.

In Chapter 3, you tell the story of how Suzuki brought a samurai sword to New York, and personally presented it to Harvey Weinstein while shouting “No cuts!” As you may know, Miyazaki has told a slightly different story to Western media, in which he claimed Suzuki mailed a sword to New York, with the “No cuts!” message attached to the blade.

I would be personally very curious to know exactly when and to whom Miyazaki told this story. While I was at Ghibli I think I was with him for every single one of his foreign press interviews and I never heard, or even heard of, him telling this story. [NB: One press source for this story is an interview with Miyazaki published in the British newspaper the Guardian in 2005.]

Nothing is impossible, but I think the most likely thing is that it's a misunderstanding amplified by mis-translation and inaccurate re-telling. All I can say is that I was present for all of the original story from its conception, to the purchase of the sword, to its delivery to Mr. Weinstein.

You mention that Miyazaki saw clips from Disney's upcoming film Fantasia 2000, but that he said the footage was terrible. As it happens, Fantasia 2000 includes one segment (“The Firebird”) which has imagery which somewhat resembles Princess Mononoke. I wondered if you remember if any of this imagery was in the footage Miyazaki saw, and if any of the Disney staff indicated if Fantasia 2000 might have been influenced by Princess Mononoke??

I'm sorry but I don't remember what footage we were shown that day. As I recall, no one mentioned Princess Mononoke. We were in a hurry and it was an unauthorized addition to our Disney itinerary. The Disney executive in charge of our visit was angry that the animators had slipped it in without asking him, but Miyazaki said he would prefer looking at animation to having a fancy lunch, so everyone else in the group proceeded to lunch while Miyazaki and I joined the animators.

I subsequently saw Fantasia 2000 in a large theater with a live symphony orchestra in Tokyo. The memory of that gala event has somewhat overlapped the memory of having seen random footage earlier.

I have come to regret putting that episode in the book. When it's mentioned in isolation like that it gives the impression that Miyazaki doesn't respect Disney animators. This is definitely not true. I mentioned the incident in the book as part of something else. The difficulty of translating I think.

In 2005, Ghibli became independent of Tokuma Shoten. Suzuki has referred vaguely to “various circumstances,” but can you say anything about why this happened? You make clear in the book that Tokuma Shoten was declining catastrophically, even before Yasuyoshi Tokuma's death. However, if Mr. Tokuma had lived longer, do you think Ghibli might have stayed with Tokuma Shoten?

Suzuki-san's explanation is completely accurate. If Mr. Tokuma had lived longer, a lot of those “various circumstances” would also have changed.

Regarding Mr. Tokuma, I was startled by your reference to his “fond memories of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” Later you mention that his favorite enka song “had certain connections to extreme rightwing nationalists.” Can you say any more about his political leanings?

My bad. Sometimes I'm a little too fond of my private jokes.

In terms of the political spectrum it would be very hard to place Mr. Tokuma. He was apolitical in the sense that he himself had, and he had friends and close associates who had, political views all over the spectrum. I can't say if this was true, but several people told me that during WWII Mr. Tokuma was jailed as an anti-war liberal. At the same time if there were such a thing as Political Correctness ratings, Mr. Tokuma's would have been the lowest of the low. He was a person of a certain era and grew up with the beliefs and prejudices that were common in his day. I'm not condoning it. Just trying to understand it and balance it with the better parts of his character.

Tokuma-shacho was a very complicated and fascinating guy from another era. Definitely worth a book.

I loved the character of Castorp in The Wind Rises (who is the character on the cover of Alpert's book; he was voiced by Alpert in Japanese and visually inspired by him). In the book, you describe how arduous the process of voicing a Ghibli film is for Japanese actors. How tough did you find it yourself?

Well, I'm tone deaf and I had to memorize and sing a song in German, which I don't speak, so…definitely no cake walk.

When Hayao Miyazaki asked me to do the voice of a character in the Japanese version of The Wind Rises, I was of two minds about it. On the one hand I realized that I don't have the talent for it. That would be a realistic appraisal and not false modesty (in Japan you have to do something spectacular to earn your false modesty). On the other hand, how could I possibly say no to a request like that? You think, well, he's the director, he must know what he's doing, and if he doesn't there's always digital correction.

Being in the original Japanese version brings a big responsibility and a lot of pressure. The animators have put in a lot of time and effort and used their tremendous skills to bring the character to life. The studio only makes a film every two years and could collapse if one of its films failed. You don't want to be responsible in any way for screwing it up.

If I wasn't feeling enough pressure about doing the role, Suzuki, the film's producer, upped the stakes by arranging for a series of press interviews and interviews by the two teams of documentary filmmakers recording the making of the film for posterity. At every possible opportunity I was asked if I was nervous about doing the role and if I thought I was up to performing my lines in Japanese. The documentary teams also followed me around before, during and after the recording sessions.

In voice recording even the most talented actors have to do each line over and over and over again. For recording the small role of Castorp they scheduled enough time for me to say each of my lines 50 times or more. It took Yūko Tanaka, an immensely talented actress [who voiced Lady Eboshi in Princess Mononoke], 50 tries to say part of one line; “kunikuzushi ni fusawashii” ["it's perfect for bringing down a nation]. So I wasn't going to worry if it took me a dozen or two dozen tries to say “ano wakamono uchihishigareteita,” a phrase that in the 30-odd years I lived in Japan I have never heard a single person utter. Not once.

When you're in the recording booth recording at Ghibli you can look up at three small screens mounted in one corner of the room near the ceiling and you can see how the director and the producer in the control room are reacting to your line readings. In Japan you're not always alone in the recording booth. Ghibli uses an extremely talented and energetic woman, Kimura-san, a professional voice coach, to help and encourage the actors as they perform. She provides hilarious, no-holds-barred, on-the-spot feedback on your performance. If you don't quite understand what Miyazaki is telling you to do, after many Ghibli films, she does.

Hayao Miyazaki listens to you read each line with his head down and his eyes closed. At the end of the reading, his arms stretched high above his head forming a circle is a “maru” – well done. His arms stiffly folded across his chest is a “batsu” - bad. One maru out of ten tries is pretty good. As in baseball, three hits out of ten at-bats is professional-level success (70% failure rate). If you happen to go 0-for-50 on a line, they skip it and you come back to try it the next day when you're fresher and have more energy. Kimura-san is there to provide limitless enthusiasm and encouragement, and she tells you not to worry. Some lines you just nail. Others take more time.

Once or twice during my solo rendering of the song “das gibt's nur einmal”, maybe on my 60th or 70th time through it, I looked up to see Suzuki with his arms folded stiffly across his chest, leaning way back and looking up sadly at the ceiling (batsu). Miyazaki had his head on the desk weeping (batsu-minus). All I can say is that Yūko Tanaka wasn't asked to sing in German.

The first day of recording went better than the second day. When you do well on the first day of recording, and you are not a professional, you may get a little cocky when you show up for day two. Some of the fear and tension that leads to a better performance might have dissipated. On day two Miyazaki was less happy with my line reading.

At one point the character on screen was drinking wine and after more takes than I would like to own up to, Miyazaki sent down a bottle of red wine and ordered me to drink a glass before trying the line (each time). When that didn't work he commented that the wine they provided me with probably hadn't been expensive enough (in the credits in Miyazaki's later films each person is represented by an icon – mine is/was a wine bottle).

In The Wind Rises, Castorp' s scenes are with Jiro, who was voiced by Hideaki Anno. Were you in the same recording sessions as Anno?

No, it's one person at a time. But everyone does have the incredible Kimura-san there with them to help.

When The Wind Rises was dubbed into English, “your” character was dubbed by the great German director Werner Herzog. Do you have any comment on this, and have ever been able to meet Herzog?

No, unfortunately. I was asked to play Castorp in the English language version but I declined. In Japanese Miyazaki was looking for a certain something that he thought my voice had. But he doesn't supervise the English versions and I know I would have been a bad choice. I thought it should be Christoph Waltz.

In Chapter 5, you describe how Joe Hisaishi created an expanded orchestral score for Castle in the Sky for the Disney dub. You said Miyazaki vetoed this score. However, the Disney English-language dub for Castle in the Sky does indeed feature a much-expanded score by Hisaishi. Did Miyazaki change his mind later, or was there another reason why the score made it into the dub?

I'm afraid I don't know. That would be something that happened after I retired.

My last question concerns the first line of your Introduction. You say, “Studio Ghibli was for more than three decades Japan's best-known and most successful creator of hand-drawn feature-length animated motion pictures.” Is your use of “was” an indication that you think Studio Ghibli's time has now passed?

My use of “was” is by no means an indication that I think Studio Ghibli's time has now passed. It surprises me that anyone would think that. No one is more eagerly looking forward to How Do You Live? than I am, and to the ones after that which are now in the planning stages.

Thank you to Stone Bridge Press for the interview opportunity. You can read Osmond's review of Alpert's book Sharing A House With The Never-Ending Man: 15 Years At Studio Ghibli here

discuss this in the forum (12 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history