The Mike Toole Show

Holy Terra

by Michael Toole,

Ever heard of the Showa 24 Group? The 24th year of the Showa era was 1949, a time when Japan was still in a chaotic period of postwar occupation and recuperation, a good few years before the gears of their miraculous recovery from World War II would lurch into motion. In that year of 1949, the famous shoujo manga artist Moto Hagio, of Heart of Thomas and They Were Eleven fame, was born. Minori Kimura, another artist of considerable renown in Japan but unknown amongst English-language manga, was born in that same year. Spread that date range out a teensy bit, and suddenly the group expands to include Riyoko Ikeda (Rose of Versailles) and Toshie Kihara (Angelique) and Yasuko Aoike (From Eroica with Love), plus many others. If you study manga closely, you've heard of the Showa 24 Group, sometimes called the Year 24 Group. Shoujo manga scholar and translator Matt Thorn calls them the Fabulous 49ers. I like that.

For me, the most fabulous of the 49ers is Keiko Takemiya, who was actually born in 1950. What the 49ers accomplished is pretty damn important—it's easy now to look at the field of shoujo and josei manga, which are largely written and drawn by women for their female target audiences. But this wasn't always the case; when the genre emerged in the 50s and 60s, the stories were typically created by men. Good men, the likes of Osamu Tezuka and even Leiji Matsumoto, but still men creating comics for girls. The 49ers successfully broke into manga in a big way over the course of the 60s and 70s, pushing the aesthetic and storytelling boundaries of shoujo manga with breakout hits like Rose of Versailles and Eroica. My favorite 49er manga? Toward the Terra.

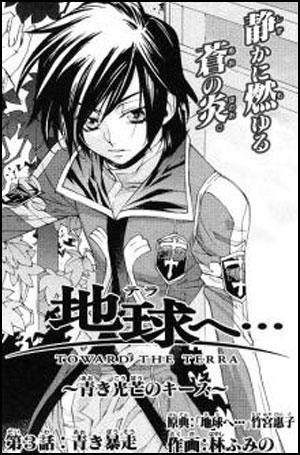

Toward the Terras's gotten the anime treatment a couple of times, with both format and a gulf of over 25 years serving to produce similar yet surprisingly different results. Interestingly, though, the anime's comic basis is not shoujo manga—at least, not in a strict demographic sense. It ran in the pages of Gekkan Manga Shonen in the late 1970s, alongside a fascinating array of long-form SF comics and shorter pieces – fare as diverse as Tezuka's Phoenix, Satomi Mikuriya's NORA (I really like the OVA of this, and wish it would come out DVD somewhere—anywhere!), and Katsuhiro Otomo's SOS! Tokyo Metro Explorers. Keiko Takemiya had previously established herself with shoujo and shounen-ai fare (her Song of Wind and Trees won the Shogakukan manga award in 1979; both it and her fine Door into Summer would eventually be adapted as anime as well), but Toward the Terra quickly became her broadest hit, winning the inaugural Seiun award for manga and soon jumping formats: first to a radio drama, and then to a feature film.

Before I talk about what makes the film so interesting, I'll touch on the manga itself. It's fascinating, simply because of its sheer scope. Echoing western SF fare like J.G. Ballard's Deep End and the film Silent Running, Takemiya shows us a future planet Earth where, faced with an exhausted ecosystem, mankind leaves, ostensibly to allow the planet to recover. But straightforward deep-space colonization efforts just result in mankind becoming fragmented (planetary settlers quickly start to see the Terran authorities as “aliens” and ignore them), so a system, dubbed Superior Dominance, is established: kids come from test tubes, are matched to surrogate parents in sprawling “educational cities” devoted to their early development, and summarily (and, usually, traumatizingly) brainwashed at age 14. From there, the great and the good rise to become Members’ Elite, the cream of the crop who administer the SD system and get to visit the blighted, still-in-recovery Earth. Regular folks of ordinary intelligence instead serve the vast interplanetary machinery that makes up the SD system.

It's compelling stuff right off the bat, and Takemiya sweetens the formula by introducing the Mu, an unexpected evolutionary wrinkle in the SD system plan. Most test-tube kids thrive under SD's conditions, but a select few are born sickly or handicapped. More often than not, those infirm few develop telepathy and psychokinesis to compensate for their frailties, making them dangerous to SD's carefully planned system. Leading the Mu out of the darkness of oppression from their fearful human captors is Soldier Blue, the first telepathically-awakened Mu to escape from the SD regime. Almost three hundred years later, Soldier Blue conspires to liberate his people and make for Earth, even as the SD system churns out wave after wave of callow recruits for their cosmic treadmill. A boy named Jomy Marcus Shin emerges as a Mu – and not a feeble or stunted kid, but a hardy, resilient, smart boy with psychic reserves as deep as Soldier Blue's. On the opposite side, a secret Superior Dominance program to produce an ideal leadership candidate gives rise to Keith Anyan, the only human with enough intelligence and pragmatism to see the reality of humanity's situation without interference from his own emotions. Thus is the stage set for awesome, multi-generational interspecies conflict, as the gentle but fiercely protective Mu push back hard against the feckless, domineering human SD empire.

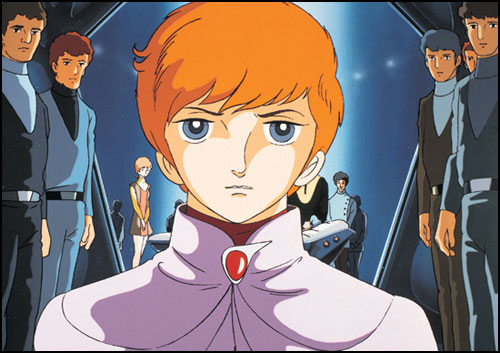

Toward the Terra, which can be easily had in manga form in three 300-page volumes from Vertical under its faithfully-translated-from-Japanese title To Terra…, was fast-tracked for feature film development by Toei after the massive domestic success of Galaxy Express 999. But while GE999 would put its group of top animation talent to excellent use, Terra was steered by Hideo Onchi, a filmmaker of some renown—but one who'd never before worked with animation. Onchi was more used to modestly-budgeted feature films and TV series. To convert Takemiya's vision to the silver screen, Onchi recruited mechanical designer Akira Hio, who'd go on to make his mark designing Albegas (hey, remember the weird gladiator Voltron? Yeah, Albegas was that guy!), and character designer/animation director Masami Suda, a Toei lifer whose resume is a bit low on really high-profile projects, but certainly not low on works (hey, he was animation director on those NORA OVAs!). With this staff, the film is bold and colorful, but oddly workmanlike—Onshi treats the animation camera a bit too much like a film camera, favoring slow pans and rotations over truly dynamic movement.

But those are just some technical details. In spite of the odd staff lineup, Toward the Terra's film production reflected its status as a rapidly-rising cultural touchstone. Lead actors Junichi Inoue and Masaya Oki recorded parts of their dialogue in cosplay as their characters, and the film even sports a pair of amateur seiyuu contest winners providing incidental voices, one of the first productions to use a method that's employed fairly regularly as a PR stunt these days. Defying Toward the Terra's stately, epic feel is the movie theme song, a peppy disco number by Da Capo (you thought it was an anime, but it was a musical group way before that!) entitled “Coming Home to Terra.” The film compresses a great deal of the manga's broad storyline, greatly reducing the role of Keith's early foil, Seki Ray Shiroe, and turning Jomy's disciple Carina into his lover, making him the father of the film's emerging hero of the third act, Tony. This isn't the case in the manga—very interesting! Despite the sometimes boring camerawork, I'm very fond of this rendition of the story – the musical score is fantastic, and the monaural, slightly tinny soundtrack makes the proceedings seem dreamlike at times. Years later, Onchi would admit that, despite being his only animated film, Toward the Terra is probably the most important, far-reaching movie he's directed. We're fortunate to have an easily-available DVD from Nozomi Entertainment, which was struck straight from Toei's remaster. Back in Japan, fans get to enjoy the movie in blu-ray, with the added extra of a deleted scene—a real rarity in any anime production!

Anime/manga franchises spinning off complementary film or TV projects is commonplace. It's practically expected now, with franchises like Bleach and Madoka Magica making their presence felt on both big and small screens, and it was also routine circa 1980, which saw the likes of Galaxy Express 999 and Space Adventure Cobra dance adroitly between TV sets and movie houses. But while Toward the Terra made the jump from the printed page to movie theatres just fine, there was no TV deal forthcoming. Instead, Toei rewarded Takemiya by greenlighting a production of her Door into Summer; but while the film was backed by Toei, it was animated at Madhouse, directed by the incomparable Toshio Hirata. A fine film indeed, and arguably the first great shounen ai anime. Toward the Terra would take a bit longer to emerge as an anime TV series—about 27 years later, in fact.

You can imagine how distant the final product might feel from Takemiya's classic manga. But intriguingly, it's not that far from the original at all. Instead of altering key details, the TV show's new staff, including key creatives like Yutaka Izubuchi (who provides designs and steers the overall look of the show), character designer Nobuteru Yuuki, and director Osamu Yamasaki, expand on the original, introducing great new characters on both sides of the conflict and expanding the battles on Terra itself and on Naska, the Mu's temporary homeworld. The TV series does make numerous changes that set it apart from both the original manga and the film, but one of them really stands out: it's how Soldier Blue is treated.

See, to me the biggest weakness of Toward the Terra in both manga and film form is that, while Jomy is a pretty cool character, he's nowhere near as intriguing as Soldier Blue, the spike-haired scion of the Mu, who's doggedly persevered in his resistance to humankind for three centuries, and who also wears a really cool cape and psychic amplifier. He's decisive where Jomy's hesitant, fiery where Jomy rejects the idea of fighting, and slings around enough raw ESP to push aside a planet-busting megaweapon. Izubuchi and his staff really understood this fact, and they've dealt with it by giving Blue a vastly increased role in the TV series. The character fades quickly in Takemiya's original story, but in the TV show he sticks around to fight off the bad guys, who are nakedly fearful of him and his reputation. He even flies around in space, unaided, because that's how much ESP he has. Man, remember back in the 80s how everyone had ESP? Kimagure Orange Road, ESPer Mami, Cosmo Police Justy, Locke the Superman… who's got ESP these days, anyway?

All of the other changes in Toward the Terra TV are to add to story and further humanize the characters. Jomy presides over the first natural birth in centuries courtesy of Carina… and Leo, one of Jomy's first friends among the Mu. Keith Anyan learns much from the rebellious Seki Ray Shiroe before he's pitted against him; later, he's paired up with Makka, who's present but quieter in the older versions, a self-loathing Mu hiding his powers. Keith keeps his secret to use him as a pawn, but in the back of his mind, a doubt nags at him: if he can tolerate and even befriend Makka, why can't humanity put up with the rest of the Mu? There are other colorful TV-only characters too, like Glave Murdock, a human fleet general. Murdock's greedy, opportunistic and a bit cruel to his rivals, but still a professional officer who recoils in disgust at the idea of executing innocent prisoners. While Takemiya paints in broad strokes in her manga, incorporating elements of 1984 and Brave New World and heck, maybe even Logan's Run (the movie came out in Japan several months after Terra's debut, but it's easy to picture Takemiya quietly working its snappy jumpsuits and dystopian cityscapes into the mixer…), the new TV series is even broader still, a show I found myself enjoying more and more as it progressed.

Of course, the 2007 TV Toward the Terra is the one that's starting to slip out of sight, in terms of availability. Bandai Entertainment pumped out spare, subtitled-only 2-disc sets in their latter days, but the prices are starting to creep up on those. There's even a dubbed version, but it's not included on the discs. That might be just as well, as the dub is produced by Telesuccess Productions, a Philippines localization house known for quick but unexceptional work. Still, Toward the Terra hasn't been rescued by Funimation or Sentai Filmworks (its status as an Aniplex show probably makes it something of an orphan), so I hope that Aniplex USA puts it up on Youtube, so I can tempt you into watching it and they can earn a little ad money.

It's funny, I've discussed the differences in production between the Toward the Terra movie and TV series, but let's not forget that this all came from manga. As stated earlier, Takemiya's manga has a very delicate, shoujo-esque aesthetic, despite being written and drawn for a boys’ magazine. With its sleek heroes and numerous ambiguous character relationships, it'd be pretty hard to tell this was a shonen title without noting its origins in a shonen magazine. Despite its placement, Toward the Terra was (and is) popular with women and girls, particularly the driven, troubled Keith. He even got his own spinoff manga that ran concurrently with the 2007 anime.

As you might guess, it's shonen manga. But it's shonen manga of a new breed – the kind of shonen manga that women read in larger and larger numbers. Remember how popular fare like Black Butler and One Piece are with ladies? I feel like Toward the Terra's crossover appeal was a harbinger of this current state, where shoujo manga in general sometimes seems to gradually retreat to something more akin to a stylistic choice than a full-fledged, diverse genre. Indeed, despite the moving sidewalks and space leisure suits, Toward the Terra rarely feels dated. The three manga volumes from Vertical are still mercifully inexpensive and easy to find. If you love good, involving SF manga, don't leave them waiting!

Ultimately, which version of Toward the Terra is the best one? Takemiya's comics retain tight focus and pacing, creating a sprawling multi-generational tale that can still be read in a single evening, provided you're a freak who looks at 950 pages of manga and says “yeah, I can kill that in a few hours.” (I'm that guy!) Onchi's film has the most extreme onscreen violence, but it's probably the original manga version that has the most actual death. The film has the best soundtrack, but its character designs are kinda rough (Jomy never even wears his own cool psychic amplifier, like Soldier Blue's, while he does in the other two versions! Weird.). The TV version is the broadest, freshest, consistently the best-looking, and most ambitious, but it suffers a bit from pacing issues at the end. Ultimately, though, all three versions tell a universal story of pride, struggle, and conflict. You'll find parallels for every 20th and 21st –century ethnic, social, or cultural conflict you can think of in here. The real magic of Toward the Terra, Keiko Takemiya's masterpiece, is that consuming one version will only lead you to seek out the others.

Have you traced a modern TV series back to an older feature and even older manga? For example, did you try out last year's Jojo's Bizarre Adventure TV show, work your way back through the OVAs, and then doggedly chase down those Viz manga volumes? Did you start with Imagi's competent but flopped Astroboy movie, and work your way back to Tezuka's 1950s manga? Have you discovered that reading one version of your favorite enhances your appreciation of the others? I felt that way with Toward the Terra, and I'm feeling the same magic coming from the still-elusive Yamato 2199, a remake of the classic Space Battleship Yamato. Tellingly, Yutaka Izubuchi is involved with that one, as well. New fare is always welcome, but there's nothing as cool as keeping a classic alive, is there?

discuss this in the forum (19 posts) |