Anno, Itano, and the Apocalypse: Intergenerational Struggle in Megazone 23 and Neon Genesis Evangelion

by Jonny Lobo,In anticipation of AnimEigo's Blu-ray release of Megazone 23 and the theatrical premiere of the final Rebuild of Evangelion film, I found myself comparing the two franchises whilst in not-so-splendid isolation this past year as the world around me seemed just a little too eager to collapse. Though the former has had new projects successfully crowdfunded and the Neon Genesis Evangelion brand has been greatly enhanced by the Rebuild films, I am mostly concerned with their earlier entries. Long venerated by aging otaku and cinephile subcultures across oceans, these mecha-themed masterpieces helped redefine the anime industry in their respective eras. True enough, Megazone 23 and Evangelion are creatively distinct entities, each as different from the other as either one is from anything else comparable. But as emblematic of the 1980s and 1990s as they may respectively be, there are more than a few common threads linking the two together. Moreover, although most anime viewers tend to think of Evangelion as more readily melancholic and critical of society than the comparatively obscure Megazone 23, I contend that both contain equally strong indictments of previous generations in their respective depictions of the apocalypse.

A rarely touted tidbit about Evangelion director Hideaki Anno is that he worked as an animator on the original Megazone 23 OAV, which was released on home video in 1985. Amid his roaring twenties, which included the presentation of short films for DAICON and impressing even the likes of Hayao Miyazaki with his work on Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, a young Anno was one of many freelancers in the 1980s contributing his talent to Anime International Company, Inc., better known as AIC. Along with Victor Entertainment, AIC produced Megazone 23 as an original video animation after unsuccessful efforts to secure sponsorship for a television series. Crafted by some of the same hands that would also contribute to the groundbreaking Bubblegum Crisis OAV, Megazone 23 surpassed initial sales expectations in Japan. Its success contributed to the industry's continued practice of prioritizing home video releases for original animations and even previously aired television shows, boosting nascent overseas anime fandom which, prior to internet streaming, heavily relied upon such physical exports.

Another notable name attached to Megazone 23 is industry veteran Ichirō Itano, famous for his signature style of animating action sequences which affectionately came to be known as Itano's Circus. Though he was instrumental in the original OVA (labeled as Part I in relation to later installments), Itano made his directorial debut overseeing the 1986 sequel, Megazone 23 Part II. Both he and Anno had previously worked on Space Runaway Ideon and The Super Dimension Fortress Macross as the latter artist was just beginning to go professional. Working on these productions proved to be a source of valuable experience for Anno, who viewed Itano as a sort of mentor in the early stages of his career. At the Tokyo International Film Festival in 2014, he even went so far as to attribute his admiration for Itano's work on the Mobile Suit Gundam franchise as the reason he ultimately pursued his own prolific career as an animator.

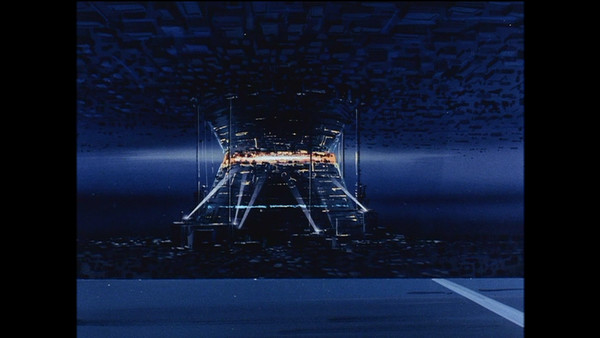

It is somewhat surprising, then, that Megazone 23 has not been thought of as a precursor to – if not possible inspiration for – Neon Genesis Evangelion with the same enthusiasm as, say, Space Runaway Ideon or the gargantuan Ultraman franchise. The otherworldly us-versus-them dynamic certainly appears in both (not exclusively, of course), as the remnants of humanity mount military struggles against uncanny opponents for survival. Biblical eponyms offer a purely aesthetic value of exoticism as much as serving any symbolic purpose in Megazone 23, and are deployed to similar ends in Evangelion (and other works like Nadia - The Secret of Blue Water, an earlier Gainax series also directed by Anno). The concept of an underground city beneath the Tokyo of a bygone age – complete with massive moving mechanisms shielding it from the world above and concealing government secrets – features prominently in the two titles; so too does technology acting as a mother figure to misguided teenagers.

There are also extraterrestrial elements in both plots, with humans embarking on desperate missions of self-preservation as rationale for war against unexpectedly humanlike enemies. These encounters occur against backdrops of global catastrophe, provoking existential questions for characters and audiences alike. In their own respective ways, both question presumed relationships to reality: external circumstances compel youthful protagonists to challenge themselves and confront societies already crumbling under the weight of epistemological crises.

While this sort of internal conflict in Evangelion is more psychoanalytical in nature, in Megazone 23 the human relationship to technology and its capacity to construct or reinforce alternative realities is interrogated more robustly. The notion that computers could confine people to superficiality so powerfully presented in Megazone 23 was such a brilliant take on Plato's allegory of the cave that many initially believed it must have influenced The Matrix. (The Wachowskis, who are quite candid about their appreciation for anime, have indicated that this was not the case.) Amid these and other metaphors for barriers found in Megazone 23 and Evangelion, however, are common themes of growth: adolescents colliding with adulthood; humanity collectively maturing from a figuratively juvenile state; multiple forms of rebirth reachable only after personal growth, and painful recovery from being blinded by the sunlight that exists beyond the dimly lit walls of our own minds. These works are preoccupied with the loss of innocence, with respect to childhood as well as humankind in its cosmic infancy, and how we might respond to the challenges of growing up.

Both series offer a harsh examination of authority, which, on a large scale, is often maintained by political maneuvering but ultimately realized through military might. There are several sets of conceptual lenses through which this subject could be viewed, e.g. authoritarianism, industrialism, and militarism. Key to any well-rounded understanding of Megazone 23 or Evangelion, however, is the consideration of intergenerational conflict alongside various possible messages. Due in large part to the televised broadcast of Neon Genesis Evangelion in the 1990s versus the direct-to-video release of Megazone 23 in the decade before, to date the popular Gainax production has received far more attention in this matter.

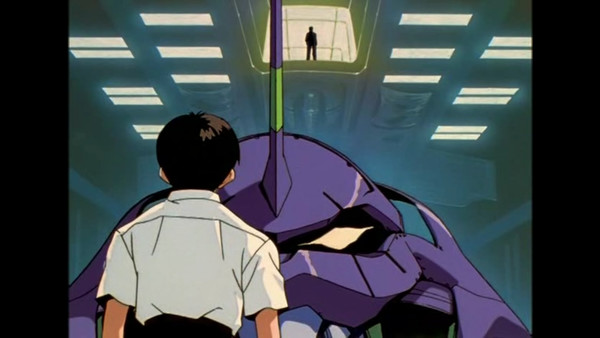

The animosity between Shinji Akari and his father continues to fuel innumerable jokes and memes online as well as detailed discussion. This relationship between a specific father and son is representative of the generations to which each belongs. Focusing on Misato in his piece for Anime Feminist, Anthony Gramuglia references Japan's lost generation (roughly the equivalent of millennials in the US) while pointing out how the show presciently anticipated many of the ills currently faced by young adults inheriting a broken world from their parents. The struggles of bearing Herculean expectations while simultaneously being disrespected or even opposed by those who should be supportive is channeled perfectly in Evangelion through characters like Misato and her juniors, tasked with defending all of humanity as they navigate their own untreated trauma. In NERV and SEELE, there are leaders but not much leadership; in Anno's Evangelion, good role models are hard to find.

Much of the same can be said about the world of Megazone 23 in which Shogo Yahagi finds himself, where parental figures are almost entirely absent. Rebellious rage is directed toward the government, the de facto enforcer of patriarchy, rather than an individual like Gendo Ikari. After becoming a veritable man who knew too much, Shogo and his peer group become the targets of assassination by shadowy government agents. A transforming motorcycle and a ubiquitous virtual idol are the only allies available to him and his girlfriend, Yui Takanaka. Part II thematically continues this narrative as Shogo, Yui, and a biker gang of delinquents evade the authorities before directly confronting the police in a deadly brawl. In an interview accompanying later releases of Megazone 23 by ADV Films, Itano explicitly states that these fight-the-power feelings came from a very personal place. As a relatively young person himself at the time, Itano felt that “the adults that were around were crap and not role models.” After mentioning notable exceptions like Noboru Ishiguro, director of Part I, and other senior staff members, Itano says that “when I was a director, there were no adults that were good role models at the sponsor or the production company.” In addition to expressing his angst about the lack of role models in his workplace via Megazone 23, Itano also inserts therein his need for such figures in curious ways: the antagonist BD, for example, was portrayed as yet another adult in leadership using despicable things to his advantage, but “in a positive way” according to Itano. Perhaps in his self-professed worry of getting “preachier” with age, Itano attempted to prevent Part II from being remembered solely as a diatribe against his elders. Nevertheless, both Megazone 23 and Evangelion demonstrate that when there is a lack of guidance in our lives (whether parental in our formative years, or more broadly societal in the wider world), we seek to fill these vacuums with substitutes wherever we can find them, healthy or otherwise.

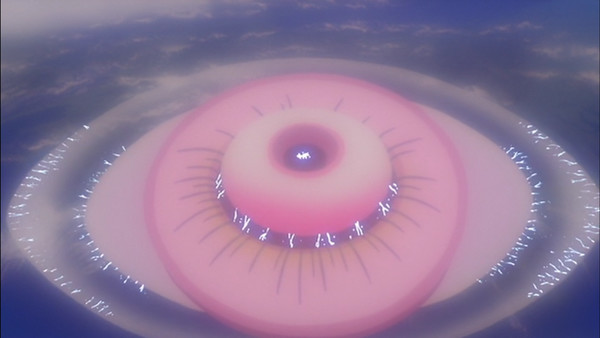

Crafted as expressions of human emotions and evaluations of man-made systems, neither Megazone 23 nor Neon Genesis Evangelion offer systemic solutions to what both implicitly portend as an impending collapse of civilization. In fact, each narrative begins in a post-apocalyptic setting. Whether it be “Himitsu Kudasai” in Megazone 23 Part II or “Komm, süsser Tod” in Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion, footage of widespread destruction accompanies music that is both melancholic and rapturous. The unsettlingly palpable takeaway is that large-scale unmaking is both inevitable and cyclical; only the outcome of such a cataclysm, whether it serves as crucible or final ruin, can be contested. Both of these titles are truly nihilist to some degree. They suggest that our institutions cannot save us from ourselves, and a reckoning is unavoidable.

The end-of-the-world feel to Evangelion reflects the global zeitgeist of fear and possible transcendence at the turn of the century: Y2K unease was a real phenomenon, and the Left Behind franchise was successfully capitalizing on the beliefs of many Christians in the rapture. (High-ranking officials purposefully instigating Third Impact as part of a prophecy still hits close to home in the US, where the current challenges of combating environmental damage regularly clash with longstanding ideas about the end times.) And like Bubblegum Crisis describing a boom-and-bust cycle, Megazone 23 predicted that the carefree excesses of the period (when Japan and the US were riding high economically) could not last. Propagandistic mouthpiece Eve even tells Shogo that the illusory world around him resembles 1980s Japan because it was when humanity was at its happiest. In other words, Megazone 23 was communicating to its contemporary viewers that this is as good as it gets.

As evidenced by the depicted failure of collective human endeavors such as government, religion, and ultimately society, Megazone 23 and Evangelion emphasize the autonomy of the individual as, paradoxically, a potential solution to our survival as a species. Yui Ikari remarks in the previously-mentioned film that “as long as one person still lives” mankind has, in a sense, endured. And by surviving probable extinction, Shogo and his friends inherit the legacy of the entire human race. In dreamlike sequences existing outside of conventional space and time, Shinji and Shogo are questioned about their innermost feelings; they are asked about how they view themselves in relation to others, and the kind of world in which they would choose to live. Acting of their own volition (as opposed to governmental edicts, social norms, or parental instruction) to accept themselves and their fellow man, warts and all, Shinji and Shogo learn that even though hell is other people, it is an inescapable condition of human consciousness. We will always have conflicting desires to escape from, and be accepted by, the judgment of others. Thus merely looking inward, just like relying on our institutions to preserve society without also helping to improve them, is not a cure-all for every problem. We need other people, even though (or rather, precisely because) we are all so flawed. Hopelessness, however, is not the conclusion to be reached from watching either Megazone 23 or Neon Genesis Evangelion. Nor are we individually powerless, even though we often feel helpless. Itano says as much in his interview, stating that the youth of every generation feel lost about how to cope and express themselves. He goes on to say that even though young people might think the police or the government is bad, “I would prefer that they keep the spirit of challenging things with their whole being.” Even though Shogo in many ways fell short, the important thing is that he had a goal and actively took steps to reach it. For Itano, whether Shogo succeeded or failed is largely irrelevant: the point is that he never stopped trying his best. His decisions were his to make, right or wrong, and helped shape his destiny. Self-governance, in terms of one single human being or all of humankind, is an awesome power to wield. It is burdensome, but both Megazone 23 and Evangelion insist that we (not angels, not preprogrammed defense systems, and certainly not our ancestors) should choose our own fate.

This nuance of autonomy as it relates to authority extends beyond the stories told by either production: the way we interact with art, for example, is an interplay between authorial intent and our unique perspective. In an interview with Newtype magazine on the subject of ambiguity in Evangelion and how one interprets it, Anno expresses similar sentiments of encouragement and empowerment by saying that “we're offering viewers to think by themselves, so that each person can imagine his/her own world.” Through filmmaking, Anno appears to be advocating the old adage that life really is what you make it. Despite our internal fears and external struggles, as individuals we are ultimately the authors of our own experiences, gods in our own universes. Even when inheriting existential crises like unending war and rapid climate change (or, hypothetically, a global pandemic), how we respond to tribulation is up to us. But each generation bears the burden of shaping the future. It seems that Ichirō Itano as well as Hideaki Anno, via Megazone 23 and Neon Genesis Evangelion respectively, stress that individuality is no excuse for abdication of responsibility. Because we are all interconnected, our choices affect not only ourselves and our immediate neighbors, but also generations not yet born: and it is they, the curators of history, who will judge and act upon the deeds of their predecessors. Whatever the verdict may be, hopefully they too will be able to retain a sense of imagination, and the power to create their own future.

discuss this in the forum (3 posts) |