Brain Diving

You Fight like a Girl

by Brian Ruh,

I consider myself to be a pretty liberal and open-minded person, and I like to think that an early diet of anime had a strong role in making me this way. One incident in particular sticks out in my mind in this regard. Although I didn't own many Robotech toys, I did get a hovertank from the Masters arc for one of my birthdays. However, I didn't have anyone to drive it, so I dragged my mom to the toy store to find the appropriate character. When I handed her the package with Dana Sterling in it, my mom was rather bemused. “You do know this is a woman?” she asked. Out of all the cool characters I could have chosen, I went with one of the few female options sitting there on the shelves. Now, I'd like to say this this was a kind of Protoculture proto-feminism on my part, recognizing that women can be as tough and cool as men, but really it was probably just that she was the character that went with the tank. I simply couldn't put a different figure in the driver's seat because that would violate the continuity of what I had seen onscreen. Still, with its plethora of strong female leads and its positive depiction of “alternate lifestyles” (I'm thinking of Lancer's transvestism), I think Robotech had a beneficial impact on young minds in the 1980s.

I consider myself to be a pretty liberal and open-minded person, and I like to think that an early diet of anime had a strong role in making me this way. One incident in particular sticks out in my mind in this regard. Although I didn't own many Robotech toys, I did get a hovertank from the Masters arc for one of my birthdays. However, I didn't have anyone to drive it, so I dragged my mom to the toy store to find the appropriate character. When I handed her the package with Dana Sterling in it, my mom was rather bemused. “You do know this is a woman?” she asked. Out of all the cool characters I could have chosen, I went with one of the few female options sitting there on the shelves. Now, I'd like to say this this was a kind of Protoculture proto-feminism on my part, recognizing that women can be as tough and cool as men, but really it was probably just that she was the character that went with the tank. I simply couldn't put a different figure in the driver's seat because that would violate the continuity of what I had seen onscreen. Still, with its plethora of strong female leads and its positive depiction of “alternate lifestyles” (I'm thinking of Lancer's transvestism), I think Robotech had a beneficial impact on young minds in the 1980s.

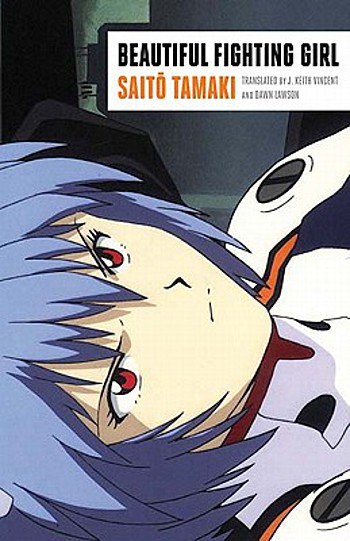

The depiction of female roles in Robotech is just one of many different ways of representing the beautiful fighting girl, according to psychologist Saito Tamaki in his book appropriately named Beautiful Fighting Girl. (Oddly for a translated Japanese author, Saito's name is given with the surname first throughout the book and on the cover. This is likely to cause a bit of confusion, so I thought I'd mention it.) Writing in the wake of successful anime with young women warriors such as Sailor Moon and Neon Genesis Evangelion (the book was originally published in Japanese in 2000), Saito tries to uncover why the fighting girl has become so popular in Japan, particularly among heterosexual male otaku.

Before I get into much more depth with this book, I have to say that I'm really quite glad that the University of Minnesota Press decided to publish it. They have rapidly become one of my favorite academic presses, and I'm not just saying that because they publish the journal Mechademia, where I'm one of the editors. They're also the ones that published Hiroki Azuma's Otaku: Japan's Database Animals (which I discussed a few months ago) as well as a book on Japanese science fiction called Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams. Unfortunately, the current market for books like this in English makes it so that only university presses can afford to take them on, but I hope they continue to release important works like this. (And just so there's no confusion regarding my praise, I paid for my copy of the book myself.)

Beautiful Fighting Girl is an important book because, as Hiroki Azuma says in his commentary at the end, it was the forerunner of a lot of commentary on anime, manga, and otaku that came out at the beginning of the last decade. Azuma notes that Saito's book came out before anyone had begun talking about Japan's soft power; at that time, if people thought about otaku at all they were those creepy nerds that you wanted to avoid. Azuma is careful to note that in reading Saito's book he was spurred into writing his own critiques of anime and otaku because he “disagreed with everything it said (with the exception of some of the finer points of its argument.” I think this is an important point to make – you don't have to be in agreement with the things Saito is saying to acknowledge that this was an important and groundbreaking work in anime studies.

I feel like I need to get that out of the way at the outset, since Beautiful Fighting Girl certainly could catch a lot of flak from fans for the language it uses. Take this sentence from the beginning of chapter six, for example: “But here I go with the straightforward interpretation that insofar as the Imaginary is governed by the principle of narcissism it will naturally be marked by polymorphous perversity.” Or this, my favorite sentence from the translators’ introduction: “Insofar as their repetition perpetuates a libidinal attachment to a fictional construct, they also challenge us to rethink our understanding of the ontological status of fiction in the visual register.” Other than the fact that both sentences use the word “insofar,” I think they also demonstrate the tone this book is trying to strike; if you're allergic to academic terms and phrases, this probably won't be the book for you. Although I'd certainly agree that writing of this type could be more clear, I think it's a little unfair when people automatically respond with a negative criticism any time analytic language is invoked for something like anime, or for popular culture in general. Think of it this way – you wouldn't just pick up a book on physics and think you should be able to understand everything in it straight away, would you? Of course not, since there's a whole discipline behind it with technical terms and ideas you might be unaware of. The same goes for a book like Beautiful Fighting Girl. I may come across as a bit defensive, but if you do read it, I want to make sure that you go into the book with an open mind.

With that said, though, I will admit to not understanding everything in Beautiful Fighting Girl myself. Since Saito is a practicing psychiatrist, he approaches the subject of anime and manga from the point of view of psychoanalysis. Now, even though I have taken multiple graduate classes on film and film theory, a number of which have referenced Freud and have employed psychoanalytic terms, I certainly wouldn't consider myself an expert in such theories. In fact, I've never really given the psychoanalytic approach much credence in my own work. Saito, however, bases much of his in-depth discussion on Lacanian psychoanalysis, but since I don't know a whole lot about the topic I'm not sure how much of what Saito says is rooted in established psychological theories and how much is his own interpretation.

The main questions Saito is trying to answer in this book are why the characters he calls “beautiful fighting girls” have come about in contemporary Japan and what this means to the otaku who relate to them. Although the term may seem self-explanatory, it's worth it to go into a bit of detail about what Saito means by “beautiful fighting girl.” He uses the phrase to refer to heroines in Japanese popular culture such as Nausicaa, Sailor Moon, and Evangelion who are young, attractive, and often engage in some sort of combat. One of the key points Saito wants to make is that such heroines are unique to Japan and Japanese popular culture. Certainly there may be strong women in Hollywood such as Ripley in Aliens and Sarah Connor in Terminator 2, but these characters are mature women, not girls. And in cases like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Saito says that they have been influenced by Japanese comics and animation, so that the general premise could be considered a Japanese import.

In the first chapter, titled “The Psychopathology of the Otaku,” Saito aims to analyze these people who seem to be so entranced by anime and manga. He goes into the etymology of the word otaku, discussing its origins in the early 1980s and how other writers such as Toshio Okada, Eiji Otsuka, and Masachi Osawa have discussed and tried to define otaku. I think Saito is really onto something when he tries to develop his own definition and distinguishes otaku from maniacs. Simply put, maniacs are obsessive collectors who try to accumulate objects and the knowledge about these objects. Otaku, on the other hand, have “a strong affinity for fictional contexts” such as those found in anime and then try to “possess” them by creating additional, personal fictions through cosplay, doujinshi, criticism, and the like. This is because anime are so immaterial that they themselves cannot be possessed. Sure, you can own the DVDs and the merchandise, but the essential qualities of the anime itself still remains beyond your grasp. As Saito puts it, “even if you owned every cel of an anime, this would not mean you owned the anime itself.”

Saito argues that the otaku's interactions with media and fictions are positive things. It isn't that otaku are withdrawing from reality into their own little worlds. On the contrary – the way otaku interact with the media is a way of adapting to lifestyles that have become saturated with media and fictions. Otaku like to play around with the idea of fiction, which is why, according to Saito, otaku like parody so much. At the core of this (naturally, given Saito's training) is sex. For someone to really be an otaku, he has to be able to be sexually attracted to images found in anime and manga that have no basis in “reality.” It's not as if the otaku is being somehow “duped,” but rather it is another level in how otaku interact with fictional worlds. And even though the “image of the beautiful fighting girl contains every conceivable sexual perversion” most otaku are relatively straightforward and “vanilla” in their real-world sex lives.

All this information about otakus is sketched out in the first chapter. From here, however, Saito takes a rather circuitous route through his later points. He is always thought-provoking, but at times it seems like he is meandering from the main ideas he'd like to develop. The second chapter, for instance consists almost entirely of excerpts from letters written to Saito by a Japanese otaku to try to explain how he sees himself and his relation to beautiful fighting girls. In the third chapter, Saito presents the results of his online interactions with foreign “otaku” (he puts “otaku” in quotes for non-Japanese fans, which seems to assert that only Japanese can be true otaku). This section is intensely unsatisfying, as Saito presents little analysis of what his respondents say, but uses them as a foil by which, through their varied responses, he is able to see “the uniformity of Japanese otaku.”

Chapter four takes us even farther away from the Japanese case into the work of an American named Henry Darger. A solitary man who lived from 1892 to 1973, he lived alone and worked blue collar jobs in obscurity. That is, until he had to move to a nursing home and his landlord, who happened to be an artist and a professor of art, began to sort through Darger's belongings. The landlord discovered an epic work, penned and illustrated by Darger, spanning over 15,000 pages, about seven young girls fighting an epic battle against an evil slave owner. This massive manuscript and other related works that Darger had been working on for decades in his apartment, led to his posthumous fame as an outsider artist. In the themes and art style, Saito sees a connection between Darger's work and the beautiful fighting girls found in Japanese popular culture. He spends a bit of time psychoanalyzing Darger in his works, saying that the insights we can gain from studying Darger will also help us to understand the otaku. It's an interesting idea, but I'm not fully convinced that Saito's Darger detour brings us that much closer to the beautiful fighting girl in the Japanese context.

The fifth and sixth chapters bring us back around to the task at hand. Chapter five proposes a genealogy of the beautiful fighting girl, tracing her from 1958's Hakujaden (Panda and the Magic Serpent) all the way through the late 1990s. In addition to presenting this development chronologically, Saito divides the beautiful fighting girls into thirteen different categories in order to better understand how such heroines function in their stories. I found this chapter to be a worthwhile exercise, but the chapter just reads like a dry description along the lines of “there was this show, and then there was this other show.” I really wish Saito had gone into more detail regarding how the creators were influenced and viewed their creations in order to give the reader a sense of the dynamic and changing nature of the fighting girl through the decades.

In chapter six, Saito gets back to discussing in more depth the reasons for why Japanese anime and manga have beautiful fighting girls, but first he needs to stop for yet another comparison with the US, this time with our comics and animation. This is key in his discussion to differentiate a particularly Japanese space and concept of time used within anime and manga. In this final chapter, Saito weaves elements he has discussed in previous chapters together with his psychoanalytic theories to arrive at the conclusion that otaku, far from being deluded nerds living in fantasy worlds, are perhaps the ones who are the best adapted to live in our contemporary media spaces. In his conclusion, Saito writes, “I fully affirm the otaku's way of living. I would never try to lecture them about ‘getting back to reality.’ They know reality better than anyone.”

I hope in the paragraphs above I have done justice to Saito's arguments. Like I said, I'm no master of psychoanalytic theories, so I certainly may have stepped on some conceptual toes along the way. This is definitely one of those books that I think I'll find myself coming back to again and again, my understanding (hopefully) deepening each time I do. It's certainly far from perfect, with the translators acknowledging its unevenness and calling it “quite a baggy monster of a book” in their introduction. In addition to its structural problems, Saito seems to have little time for otaku who may not identify as straight or male. In other words, there is certainly a lot of room for improvement. But as Azuma said in his afterword, Beautiful Fighting Girl was the catalyst for much of the in-depth writings on anime and manga that followed in the 2000s, and for that alone it is a significant book, and one I am happy to finally have a translation of on my shelves.

Brian Ruh is the author of Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. You can find him on Twitter at @animeresearch.

discuss this in the forum (71 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history