All the News and Reviews from Anime NYC 2025

The Anime NYC Guide to Working in the American Manga Industry

by Reuben Baron,

How many of the 148,000 attendees at Anime NYC 2025 want to find work in the manga business? Probably a lot of them - at least five panels focused on career-building, and even the question and answer segments on unrelated panels would frequently have someone asking, “How did I get a job here?” The manga career events took place on two separate tracks: one focused on jobs surrounding the release of Japanese manga in the United States, and the other for aspiring comic artists seeking to create their own original English-language works. For passionate fans, both career tracks promise opportunity and challenge.

Many Paths in Publishing

The Kodansha-sponsored panel “More Than One Way to Break Into Manga,” moderated by Kodansha senior editor T.J. Verentini, featured people working in different positions at different publishing companies: Lydia Nguyen (assistant editor at Abrams), Shirley Fang (production manager at Kodansha), Mark de Vera (sales and marketing manager at Yen Press), Ricky Uy (founder of Komodo), and Morgan Perry (marketing manager at Square Enix Manga). Each panelist took a different path to their jobs. De Vera worked in manga for his entire adult life, progressing from assistant to manager at Viz before joining Yen Press. In contrast, Uy worked on user interfaces in the game industry before transitioning into the digital manga space, and Nguyen worked at Starbucks while pursuing freelance art on the side. Fang initially reached out to Kodansha for a production job in 2020 and was rejected, but her portfolio ultimately led to her being hired for freelance logo design, which eventually led to her being promoted to the job she wanted.

One of the big takeaways from this panel was that any work experience gives you skills that can be applied to working for manga companies. Verentini told attendees, “Don't knock any experience you have now.” You do, however, need to know what skills are useful for which positions. For example, editorial positions require Japanese language skills to review potential licenses and verify the accuracy of translations, whereas other jobs don't have these requirements. Bookseller experience is particularly valued in publishing, and fanzines and amateur merch provide good backgrounds for production work. Connections are of primary importance for applying to jobs — it was de Vera's recommendation that got Perry past the AI filters on LinkedIn.

“Yen Press Presents: Working in the Manga Industry” covered similar ground and shared a panelist (Mark de Vera), while digging into what different roles entail in manga publishing. Thomas McAllister explained his job as editor as being the final arbiter of how a book will look and is expected to be an expert on each title. Courtney McCutchen, an assistant production editor, manages schedules and ensures that edits are implemented. Madelaine Norman is a senior designer in charge of cover and logo design, working to match the Japanese editions as closely as possible. Yen's production coordinator, Kou Chen, couldn't attend, but the panel explained that his job focused on communication and file transfer. De Vera spoke to the sales side of his sales and marketing position, involving working with distributors, managing inventory, and identifying likely hits. In contrast, panel host Ashley Spruill spoke about being a marketing and publicity manager working to promote books with media, influencers, and conventions while also handling communication between departments.

McAllister says any writing, from Dungeons and Dragons campaigns to fan fiction to Master's theses, can be used in applications for editorial jobs. McClutchen recommended knowing the Chicago Manual of Style. For sales jobs, de Vera said that knowledge of Excel is useful to have, in addition to retail experience. For marketing, Spruill noted the need to be familiar with major press outlets. During the Q&A, attendees had questions about other jobs in the industry, such as IT positions (Yen is hiring for those and almost had an IT person on the panel), writing original manga (Yen is not doing many OEL projects), and starting new companies (de Vera recommended speaking to the people from Denpa about that).

Yen Press' other panel, “Designing for the Wonderful World of Manga,” focused specifically on graphic design jobs. De Vera moderated and Norman participated on the panel alongside Yen's associate art director, Andy Swift, junior designer Lilliana Checo, and marketing design assistant Amy Chen. This panel provided an in-depth look at the process of designing books and their accompanying marketing materials. For regular volumes of manga, the golden rule is always to match the original as closely as possible. However, translating Japanese text to English means that logos and back covers require creativity.

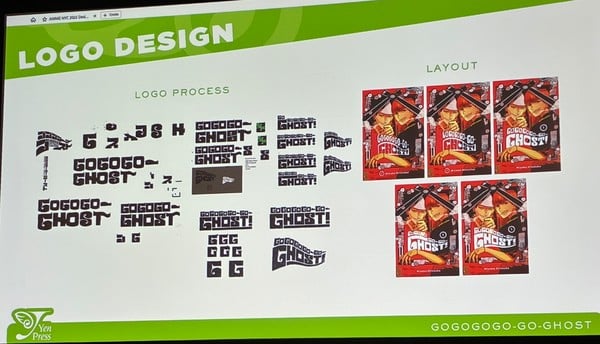

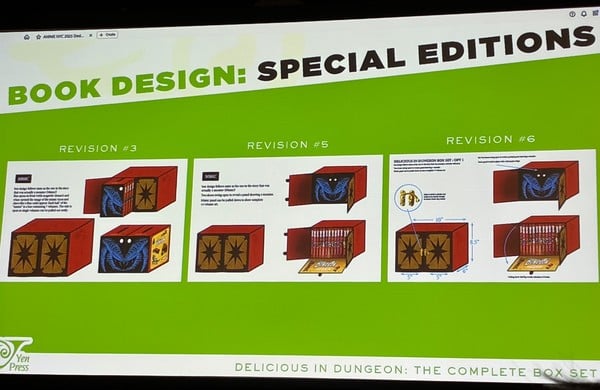

Based on a design brief that describes a manga's plot and target audience, and includes comparison logos, Norman will experiment with different fonts and designs before presenting around three versions for editors to make the final decision. Comparisons of design briefs are usually from other manga, but sometimes other sources of inspiration — for the '70s-style lettering of GOGOGOGO-GO-GHOST!, the poster for the blaxploitation film Superfly was a reference. For box sets and special editions that don't have direct Japanese equivalents to copy, designers can get extra creative — Swift showcased various drafts of his Delicious in Dungeon box set (originally, he wanted an actual 3D Mimic to pop out of the box!).

The general vibe of these publishing career panels was encouragement. The overall message was that if you know what you're good at and who to talk to, you can find a job that fits your talents in the manga business — and that if you're at these panels at this convention, you already have an advantage on the “who to talk to” part of the equation. Sometimes you could feel panelists straining to be encouraging (when someone asked if working in cryptocurrency could get him a job in manga, de Vera answered what sure sounded like a question: “Sounds like you have solid marketing skills?”). While presented as achievable jobs, the flip side to keep in mind is that these are still jobs. The workload is heavy — editors can work on anywhere from 20 to 45 books a year; marketing designers will do 10-15 projects a week during convention season — and the pay isn't necessarily spectacular.

For Writers and Artists

What if you want to make your own manga? Ignoring semantic debates about whether original English language comics count as “manga,” Anime NYC provided references for that as well. Fawn Lau, Viz's creative content director of original publishing, spoke on the “Making Manga with Viz” panel about the Viz Originals and One-Shots programs (for serialized and stand-alone comics, respectively).

Acknowledging the range of beliefs about what technically makes something “manga,” Lau emphasized certain stylistic identifiers as her standard: layout (smaller pages than other comics, with characters generally prioritized over backgrounds), sound effects (where the size of FX indicates volume, and can be very subtle), different balloon styles (not unique to manga but common within it), floating text (often used for thoughts or narration), and asides (small comments that add depth or humor but aren't critical to plot). She explained the process of writing a manga (from concept and outline to visual development, script, and thumbnails to pencils, Inks, and final art and lettering). She recommended books on the subject (Dr. Mashirito's Ultimate Manga Techniques, The Shonen Jump Guide to Making Manga, Hirohiko Araki's Manga in Theory and Practice, and Shojo Beat's Manga Artist Academy).

Viz Originals and One-Shots are open for submissions at viz.com/create, and they do portfolio reviews at conventions. Originality and layered characters are big things they're looking for—“if you're inspired by a lot of things that already exist out there and are just trying to make things just like that, that's pretty obvious to most readers” — and the ongoing Originals demand a higher standard of quality than the One-Shots. For creators wondering how to sell big series-worthy ideas in a one-shot, Lau recommends as inspiration Eiichiro Oda's pre-One Piece stories, collected in Wanted! Eichiiro Oda Before One Piece.

Getting OEL manga published in Japan is harder, but the VIZ Original Devil's Candy did, so it's possible even if unlikely. “Creating Your Lane in Comics and Manga,” returning to Anime NYC for the second time, offered a conversation between authors and artists of color currently working in comics. Bria Strothers moderated, asking questions to Lucy Camacho (Heroes Circle, IDW's Monster High), Wendy Xu (The Infinity Particle, Tidesong), Gigi Murakami (Resenter, Are You Afraid of the Dark?: The Sinister Sisters), and Tony Weaver Jr. (Weirdo, The Uncommons).

The panelists shared experiences in both traditional publishing and indie spaces. Camacho went indie since last year's panel specifically to write shojo, which too many publishers consider “niche” — “Girls media needs love too!” she said to applause. Murakami's career has gone in the opposite direction, turning her independent project Resenter into one of the first Viz One-Shots. This experience was “crazy, to say the least.” Xu talked about struggling with perfectionism, saying, “There's beauty to be found in imperfection.”

Weaver took a different tack than the other panelists when giving his “three-minute bootcamp” at the end of the panel — “They're good cop, I'm bad cop.” His emphasis was on making sure you have a business plan for your writing and know what it is you're looking to achieve, saying that, “The stories that live are the stories that get paid.” You might think of your story as your baby, but “If there were a parent who couldn't afford food for your baby, you'd say that's a bad parent.”

He recommends looking through Publishers' Weekly to keep track of what's selling. Because he struggles with multitasking, he makes writing his full-time job. He also emphasized that living in New York is a big advantage for getting published: people in remote locations can try to submit stories, “but when all the editors in the industry sit down to have breakfast, you won't be there.”

Ending on this “bad cop boot camp” left me with mixed feelings. The thing with art and creative writing in the age of the internet is that there are far more opportunities to get seen than to get paid, so the idea that one should prioritize the latter when even the former is challenging enough feels uncomfortable, even if it's also an understandable perspective. At the very least, it's clear that any craft takes practice, and all that practice will come before profit. Finding success making your own manga — however you define “success” — is a competitive field, and the path to that success isn't so straightforward.

discuss this in the forum (1 post) |

back to All the News and Reviews from Anime NYC 2025

Convention homepage / archives