House of 1000 Manga

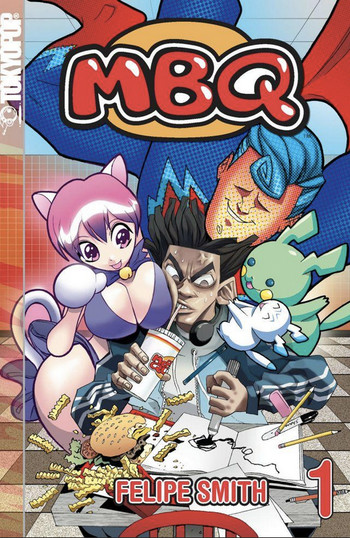

MBQ

by Shaenon Garrity,

Recently, manga scholar Matt Thorn ruffled some otaku feathers with a blog post entitled “Why it bugs me that you call your comics ‘manga’.” Although I admire Thorn above all other manga nerds, and as much as white kids appropriating Japanese culture bug me, too (albeit in a personally cringe-inducing way, since I did the same stuff when I was an poorly-socialized college nerd and had just watched my first episodes of Ranma 1/2 on VHS), I have to disagree with Thorn on his definition of a manga artist.

As Thorn writes: “It has nothing to do with ‘authenticity.’ And it's certainly not because ‘only Japanese can make manga.’ It's simply because you have not earned it, unless, like TogaQ and Kichiku Neko, your work is regularly published commercially in Japan.” Being published in Japan is useful enough as a broad definition of a “mangaka,” and Thorn, who has taught manga at a Japanese university for fifteen years, shares vivid descriptions of the artistic meat grinder Japanese art students go through to sell even one short story to a manga magazine, let alone build a career. Compared to that, some weeaboo slapping their crappy Sword Art Online fancomic on Tumblr and calling it manga looks pretty pathetic.

This image of a manga-ka as a relentless cartooning machine, forever climbing an Otoko-Zaka built from tankobon and the bones of the fallen, has an undeniable macho appeal. To draw for Shonen Jump, one must physically become a Shonen Jump character, driven by pure Friendship, Effort, and Victory. (Friendship will come in the form of encouraging faxes from your assistants, since leaving your apartment for any purpose other than editorial meetings is weakness.) It's the creative ethos championed in last week's House manga, Bakuman., about two young creators determined to become big wheels in the corporate manga machine.

But to my mind it's an overly narrow definition of both manga artists and manga, a definition in which the most authentically manga-ish manga is that produced by the mechanically honed products of boot-camp art schools, edited and marketed and reader-polled into saleable intellectual property for the major magazines. A lot of great art comes out of the mainstream manga system, and a lot of great artists toil in it. But that's not all there is to manga.

Or maybe Thorn's definition sits poorly with me because my own idea of manga is even more narrow. Maybe I do feel, deep down, that only Japanese can make manga. Maybe it takes more than publication in manga magazines to be a mangaka. And here I'm thinking specifically of Felipe Smith, who has lived the impossible dream of American otakudom, the thing I always tell aspiring cartoonists (and many ask) will happen a few hours after hell freezes over: drawing manga-style comics for Japanese publishers and getting paid and everything. But I'm not sure his work is manga. I think Felipe Smith is a publishing category unto himself.

My House compatriot Jason Thompson has already discussed Peepo Choo, which ran in the magazine Morning 2, in a previous column. But before Peepo Choo, Smith started his career the way American mangaka did in the 2000s: by entering Tokyopop's Rising Stars of Manga competition, a contest designed to flush out potential new artists for Tokyopop's OEL (Original English Language, as the kids called it in those days) line. The Rising Stars competitors were mostly young amateurs—one finalist was fifteen—allowing Tokyopop to offer contracts that would appall experienced pros. But shadiness notwithstanding, Tokyopop's OEL line provided an early platform for some genuine rising comics stars, including Becky Cloonan, Joanna Estep, Amy Mebberson, Amy Kim Ganter, and Christy Lijewski, whose Tokyopop comic RE: Play has been reborn recently as a feature in Sparkler Monthly.

Felipe Smith won second place in the third Rising Stars competition with a story entitled simply “Manga.” Tokyopop selected it for development into a continuing series, and it became the three-volume MBQ. MBQ is partly about Smith's efforts to create manga, but more about the things that make his work not manga at all. Like all the best “manga-style” Western comics, it works the elements of manga into a larger tapestry of influences, which in Smith's case include TV cartoons, hip-hop and graffiti design, American urban landscapes, and all forms of media that come slapped with an “18 and Over” sticker.

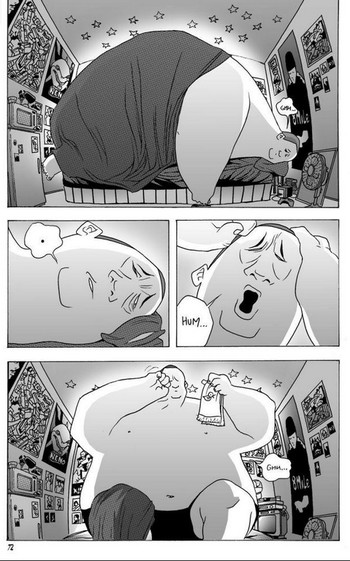

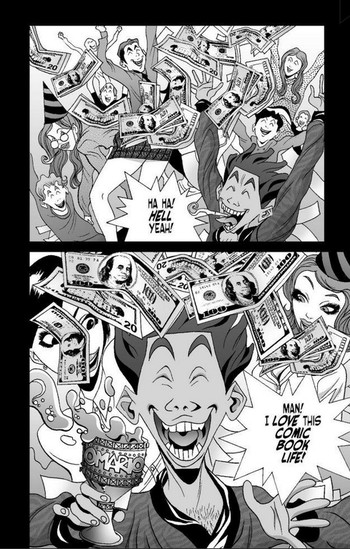

Omario, very loosely the protagonist of MBQ, is the kind of American otaku who bugs Matt Thorn and all decent people. He loudly proclaims himself a comic-book artist who's too good for the Western comics industry, but he hasn't quite gotten around to drawing anything. “Graphic novelist, comic book artist, manga-ka…call it what you like, it's just a title,” he proclaims loftily at one point. “I tell stories with pictures.” But what he mostly does is sleep, sponge off his gentle-giant roommate Jeff, and talk big to his friends. He kvetches about finding a balance between commercial success and artistic truth long before he's come close to either. When he finally draws a comic, Smith devotes almost forty pages to showing it off in all its glory. It's… revealing. A guy who explains the comics industry by saying, “The bottom line is I'm awesome, and they suck… that's the way things work, but they run things, and I'm broke,” wouldn't last a hot second with a cutthroat Japanese manga editor.

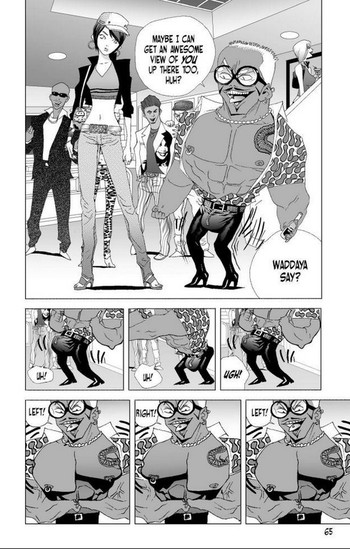

Omario only appears sporadically in MBQ. The comic is more about the world he inhabits, a world no Japanese mangaka could portray—or if one did, it probably wouldn't be a depiction best described with the adjective “balls-to-the-wall.” Omario drifts through a thick fog of characters—gangbangers, cops, convenience store workers, pro wrestlers, groupies, the guy who mops up at the karaoke studio—in an L.A. where fabulously wealthy crooks rub shoulders with petty criminals struggling to get by. His sense of place gets stronger as the comic goes on, and generic lightboxed street views give way to detailed, throbbingly alive environments.

The plot is minimal—or, rather, there are scores of plots, popping in and out of view as Smith's interest shifts. One chapter goes to a glitzy, sleazy celebrity birthday party, complete with orgy. Then we cut to Jeff heading to work at McBurger Queen, the fast-food franchise of the title. Then a disgraced rookie cop has a heart-to-heart with his senior partner. Then more orgy. Then Omario draws comics! The closest thing to a running plot involves a gang beating up a wimpy-looking fellow who turns out to have dangerous connections, setting up a showdown as the cops close in. But in the end it's not particularly important. The heart of the story is at MBQ, where all can meet as equals, a mausoleum of greasy burgers and dead-end jobs where hope goes to die—or maybe it's the place you have to start at, when you finally climb out of bed and begin the long hard slog toward your dreams.

This is not a comic for the squeamish or those possessed of taste. Smith believes in cranking every page to eleven and then penciling in some extra blood and tits just to be sure. If there's a crime standoff that can be de-escalated, it'll end in someone's head exploding into red mist. If there's an arrest, there will be police brutality. Every woman has massive sweaty breasts, and it's hardly a sex scene if it doesn't include a minimum of eight naked women. Jeff isn't just a big guy; he's ten to twenty feet tall, depending on the shot. Dee, the most dangerous gangster in the comic, has a haircut in the shape of devil horns just so there's not any confusion. Maybe the excess will turn you off MBQ. Or maybe it'll get you thinking that this isn't manga, because manga is way too timid. And yet it is manga, at least technically, because in 2009 SoftBank Creative picked it up for Japanese publication.

MBQ is currently out of print but fondly remembered. When I asked folks on my Facebook page which Tokyopop OEL titles were good, MBQ was the most frequently mentioned, along with Svetlana Chmakova's Dramacon. Both those series, probably not coincidentally, involve young American manga fans trying to make it as creators, although the similarities end there. (Why didn't I cover Dramacon for Mangaka Month? Well, to be brutally honest, I couldn't find my copies.) Tokyopop shut its doors in 2011, but not long after it quietly restarted as an ebook publisher, distributing digital editions of some of its titles. MBQ is now available on paid e-comic sites like Comixology and Scribd (for which—ethics in comics journalism alert—I recently helped launch a comics section).

As for Felipe Smith, he achieved the dream of Japanese publication and moved on to other conquests. He worked on the most recent animated Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and redesigned Ghost Rider for Marvel. He's living the nerd dream, becoming an honest-to-god mangaka and continuing to rise, doing things that should be impossible in an industry that breaks so many hearts. But what do you expect? He's awesome, and they suck.

discuss this in the forum (5 posts) |