Review

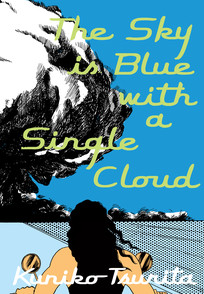

by Rebecca Silverman,The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud

GN

| Synopsis: |  |

||

Kuniko Tsurita, the first woman to contribute to GARO, explores gender fluidity, ideas of death, and what it means to participate in the counterculture of the 1960s and 70s in this collection of her short stories from 1966 – 1981. |

|||

| Review: | |||

Kuniko Tsurita may be the most important manga creator you've never heard of. That sounds like an exaggeration, perhaps, but it isn't: Tsurita, who tragically died of lupus at age thirty-seven in 1985, was the first regular female contributor to legendary alt-manga magazine GARO, and her work had a direct influence on the way that women were viewed as creators and artistic storytellers. At the time of her debut, female mangaka were looked at as somehow lesser than their male counterparts, with the prevailing “wisdom” being that women could only create works for other females, while men could write in any demographic or genre. The term in use at the time was “joryu”, which, translator Ryan Holmberg tells us, is different from what we use now (josei) in that it suggests that works created by women are inherently not the same as those created by men, that there's a “femaleness” that is very strictly defined by gender norms. (By contrast, josei is less about the gendered nature of the creator and is instead indicative of the target audience.) Tsurita defied these strictures to create stories that explored her interests and anxieties, and her few joryu works (none of which are presented here) include marginalia revealing how fed up she was with the sickly-sweet stories she was supposed to write. Although there are many different descriptors we can apply to the stories collected in The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud, “sickly sweet” is definitely not one of them. Tsurita's works are more interested in looking at what it was like to be a part of the young generation in the 1960s-70s, how gender does and does not matter, and in musing on death, something that is present throughout the volume's pieces but grows much more apparent as Tsurita's own death looms closer. Of these, one of the most striking stories is The Sea Snake and the Big Dipper from 1980. The story is presented in picture book rather than manga format, and it reads like one of Hans Christian Andersen's literary fairy tales – a mermaid with a serpent, rather than a fish, tail surfaces for the first time one day and falls in love with a star. Believing that if she follows it north she'll be able to speak to it, the sea snake goes to the North Pole, only to freeze to death gazing up at the silent celestial light that can never answer her feelings. Unlike Andersen's work, which has heavy religious overtones, this reimagining of The Little Mermaid combined with The Little Match Girl focuses on the pursuit of love at the expense of all else. The sea snake, in the end, is sad that she will never reach the star and is dying, but she doesn't regret having tried to get there. We can read a metaphor for Tsurita's own illness and her continued pursuit and love of creating manga in this – anecdotes recorded in the essay that closes out the collection note that she kept on trying to draw up until the very end of her life. Like the sea snake, Tsurita couldn't give up on her impossible drive for what she loved, and with the sea snake ending as a frozen object indistinguishable from the ice in the North Sea, Tsurita expresses her fears of being the same, without the saving “grace” of a soul or heavenly transport that Andersen's comparable works offer to their heroines. This grounding in a reality without saviors is a theme present across the works in the collection. The title story, which is one of the shortest in the book, features a lone, androgynous person in a vast, empty world wondering where everyone has gone. The sky is in fact blue, but as they ride towards the single cloud in hopes of finding where everyone else is, we can see that it is a mushroom cloud expanding over the perfect, empty world. While we can certainly take this literally – although Tsurita was born after WWII, it still would have been very recent history in her childhood – it is the alternate interpretations that make the piece really work. Does the cloud represent the changes to the protest culture of her teen years and early adulthood that is vanishing beneath the cloud of social change? Is it how she views the disease eating her? Or is it just the unpleasant truths that creep up on you as you get older and stop thinking that you can save the world? While there are no firm answers and precious few positive analyses of the tale, it is designed to make you think, which is something that nearly all of the pieces in the book accomplish. The stories do get less oblique as they progress chronologically, which may be the sign of a maturing creator or a reflection of changing tastes in storytelling. Flight, the final piece in the book, dating to 1980, has the most coherent storyline of all, featuring a romance disrupted by time travel that in some ways serves as a metaphor for those coping with the loss of a loved one. The opening story, Nonsense from 1966, is interesting but almost scuttled by Tsurita's closing admonition to re-read the story until you get its meaning, the mark of an author who doesn't entirely trust her audience to understand what she's getting at. Many of the works from the 1960s and 70s focus on themes of isolation – either in pairs or singly – and feature characters of indeterminate gender, with 1969's Occupants being an early example of a story about a lesbian couple. Tsurita draws her characters with manga-coded features for both genders – eye size, curves, etc. – so that it is almost always impossible to assign a specific gender to any one character. That may not seem like a big deal now, but at the time it was, if not revolutionary precisely, certainly largely unconventional. The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud isn't necessarily a book for the casual manga reader. It's heavy in several senses of the word (one of which is definitely weight), and the essay is dryly academic. But for scholars of manga history, Japanese feminism, or the culture of the mid-to-late twentieth century, it's a must-read. Kuniko Tsurita may not be the name most people think of when influential and important female mangaka are mentioned, but she should be. |

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall : A-

Story : A-

Art : B

+ Interesting variety of works presented in chronological order. Informative essay. |

|||

| discuss this in the forum (2 posts) | | |||

| Production Info: | ||

|

Full encyclopedia details about |

||