How Oreimo Made Little Sisters a Big Deal

by Kim Morrissy,A young pair of siblings struggle to reconnect after an event that made them drift apart years ago. Despite living under the same roof, they never speak to each other. They live separate lives, ignorant of what the other is doing—until one day, when the brother stumbles upon his sister's embarrassing secret…

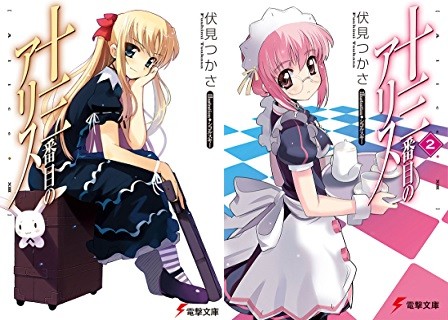

This is the plot of this season's Eromanga Sensei, but you'd be forgiven for thinking of Oreimo first, the infamous light novel series known for its ridiculously long and inane-sounding English title: My Little Sister Can't Be This Cute! Eromanga Sensei shares the same author as Oreimo and, as even a cursory glance at the summary will tell you, the same “little sister moe” theme.

It's difficult to talk about Eromanga Sensei without invoking the name of its loud-mouthed older sibling, but the differences become apparent once you look past the surface. Unlike Oreimo's Kirino, Sagiri of Eromanga Sensei matches the otaku's image of the ideal little sister: a quiet, doe-eyed girl who exudes moe appeal. And unlike the main duo in Oreimo, the siblings in Eromanga Sensei are not related by blood, allowing the romance to play out with a less direct connection to real-life incest.

These differences may seem insignificant, especially to those who don't care much for little sister romances in the first place, but they're hugely important to understanding how the “little sister” genre has evolved in light novels. Oreimo may be the defining little sister moe story of the decade, but I would argue that Eromanga Sensei is more representative of the genre. In fact, Oreimo probably became such an influential series because it deviated from so many genre norms and broadened the appeal of little sisters far beyond the eroge niche.

“What's with Japan and incest?” is a question I often see asked, frequently in relation to the little sister moe genre. I can't hope to answer such a loaded question here, but I will note that brother-sister incest is considered taboo in modern Japan, and that salacious stories about violating social taboos are hardly unique to Japan.

The little sister moe genre as we recognize it in anime and manga today arguably began in 1999 with Sister Princess, a light novel series about an ordinary young man who is made to live with twelve little sisters. The story was first serialized in the monthly Dengeki G's Magazine to a strong reception, but the video game version, which was first launched in 2001 and received multiple sequels, proved to have the most enduring cultural influence.

Before Sister Princess, incestuous themes had certainly been featured in Japanese popular culture. For example, the 1980 manga series Miyuki by Mitsuru Adachi explores a romantic relationship between step-siblings. Sensationalized stories of mother-son incest were also being widely reported in the popular Japanese press during the '80s. But it was only in the '90s, when the all-ages dating sim (galge) genre became popular, that little sisters became an object of attraction in their own right.

The main gimmick of Sister Princess was that it allowed players to choose between a normal ending and a "non-blood relation" ending where they could marry the little sister of their choice. This feature was highly unusual among games at the time, given that until 1999, the Ethics Organization of Computer Software had banned incestuous intercourse in adult computer games, even between non-blood-related siblings. The loosening of restrictions to allow sex between non-blood-related siblings ushered in a flood of little sister-themed titles.

For the next few years, little sister stories flourished, but the genre also became oversaturated with Sister Princess copycats. Audiences began to get tired of the overly peppy little sister characters and stories where nothing bad seemed to happen. Little sister narratives with a heavier focus on realism began to appear, treating incest as a serious subject. The manga Koi Kaze (2001), which was adapted into an anime in 2004, falls into this movement.

But this wave didn't last long, perhaps because the doom and gloom of the realist movement contradicted the core appeal of the little sister moe fantasy to begin with. Little sister characters weren't supposed to be realistic; they were love interests who didn't require much wooing to adore their brother figure. Even when the Ethics Organization of Computer Software revised their regulations in 2004 to allow for intercourse between blood-related siblings, romances between non-blood-related siblings remained a genre staple.

By the time Oreimo began its light novel serialization in 2008, the initial little sister boom was well and truly over. Little sisters had become a staple character archetype in eroge, but games dedicated to little sisters were niche. Oreimo introduced the world of eroge to a new audience of novel readers, but that wasn't its only innovation. The narrative combined the lighthearted tone of traditional little sister moe stories with a feeling of realism, making it distinct from the likes of both Sister Princess and Koi Kaze. The siblings bickered constantly, and the little sister was a generally unpleasant and selfish person. Kyousuke and Kirino felt almost like real siblings.

This might be why the sibling dynamics in Oreimo appealed far outside the little sister moe niche, despite the novel's constant references to the genre. Perhaps the most notable thing about Oreimo was how it convinced so many people that it wasn't about incest at all until the very end.

Tsukasa Fushimi, the author of Oreimo, didn't start off as “the little sister writer.” His debut novel, The Thirteenth Alice (2006), was a battle series involving supernatural powers with no little sisters in sight. Perhaps if The Thirteenth Alice had done well with readers, Fushimi would still be writing wholesome action stories to this day. Unfortunately for him, The Thirteenth Alice was cancelled after four volumes, leaving Fushimi to fumble for ideas for his next novel.

According to Fushimi's editor, the genesis of Oreimo was a telephone conversation between the author and editor. The editor suggested many of the elements of Kirino's character: a fashionable girl (gyaru), who acts tough but needs help from her brother, and would be relatable to otaku readers because she loves eroge.

Oreimo didn't start off as a romance. The first volume tells a simple, heartwarming story about siblings learning to reconnect. Beyond that, the story as a whole functions as an accessible introduction to otaku subculture, and the colorful cast of side characters were memorable in their own right. Nevertheless, Fushimi's editor was so struck by the sibling relationship in Oreimo that he referred to siblings as Fushimi's “fetish” as a writer. He urged Fushimi to continue writing sibling stories after Oreimo was finished.

Editorial intervention may have influenced Fushimi's branding as the “little sister” author, but according to Fushimi himself, the controversial ending of Oreimo was something he had decided on from the beginning. What solidified his decision to end the light novels with incest between blood-related siblings was his experience writing the script of the spinoff PSP game. According to him, none of the various endings in the game fully conveyed Kirino's feelings for her brother. Considering that many of the endings were explicitly romantic—much more so than the light novel itself—one can only assume that Fushimi's dissatisfaction arose from the fact that Kyousuke is revealed to be adopted in the game.

What made Oreimo so interesting as a sibling story was how it explored every possibility for a sibling relationship. In the original ending of the TV anime's first season, the story ends with Kyousuke and Kirino having a platonic relationship. In the PSP game, they fall in love as non-blood-related siblings. In the light novel, they commit the ultimate taboo. Oreimo may have taken five years to reach the confession of love, but in the end, the series celebrated little sister moe of all stripes. No wonder it caused another little sister boom, especially in light novels.

The early 2010s saw an influx of little sister-themed light novel titles making it to anime screens, such as NAKAIMO - My Little Sister Is Among Them! and OniAi. This is to say nothing of the all the light novels with amusing titles that weren't fortunate enough to get an anime adaptation, including (but certainly not limited to) My Little Sister Can Read Kanji and I Tried Controlling My Rebellious Little Sister With the Power of the Devil King.

Such is Oreimo's overpowering influence on the light novel genre that even the author's own work can feel like a halfhearted attempt to cash in on the latest little sister trend. Fushimi began publishing Eromanga Sensei in 2013, the same year he ended Oreimo—but it's 2017 now, and it feels as if the little sister trend has run its course. Viewers have been responding to the Eromanga Sensei anime with noticeably more cynicism, at least in the West.

In Japan, however, Eromanga Sensei has been doing respectably well for itself. Over a million copies of the novel are now in print, and the anime adaptation appears to be popular. Eromanga Sensei is unlikely to reach Oreimo's level of infamy and exposure, but clever marketing and cross-promotions with Oreimo have gone a long way toward strengthening Fushimi's brand power. The little sister boom may be reaching a point of saturation, but at least for the foreseeable future, Fushimi is unlikely to lose his crown as the king of little sister authors.

And what does Fushimi himself want to write, after Oreimo and Eromanga Sensei? Perhaps aware that he's been pigeonholed into a niche, he mentioned in a 2014 interview that he'll keep writing stories about little sisters. “But if I didn't have to write under the name of Tsukasa Fushimi,” he adds, “I'd like to write a horror story.”

The last time Fushimi wrote a story unrelated to little sisters was over ten years ago. Like many professional light novel authors these days, Fushimi started out as a web novel author. His experience with Dengeki Bunko may have changed his direction as a writer in more ways than he could have expected, but in the end, he still loves the freedom of web novels. These days, when he's not writing, Fushimi reads the web novels I'm a NEET but When I Went to Hello Work I Got Taken to Another World and Mushoku Tensei - Jobless Reincarnation.

“If I had to write a new little sister-themed story right this minute, I'd like to try my hand at a new setting,” he says. “I might make the characters go to another world and have adventures there. It'd be one of those isekai stories.”

discuss this in the forum (87 posts) |