Who Is The Real Motoko Kusanagi?

by Brian Ruh,If you look at the credits that have been released for the upcoming live-action version of Ghost in the Shell, Mamoru Oshii's name doesn't appear anywhere on it. The clue only that this film is an adaptation comes from the line in the credits that says "based on the comic 'Ghost in the Shell' by Shirow Masamune." Of course Shirow is rightly credited as the original creator, but the trailers that have been released so far reveal the additional debts the film owes to Mamoru Oshii's 1995 anime adaptation of Shirow's manga. In a previous article, I took a sweeping look at the Ghost in the Shell franchise as a whole, and I made the case that the many anime adaptations have tended to take bits and pieces from Shirow's manga and recombine them in different ways. (I wrote an academic article arguing a similar thing a few years ago as well.) For now, however, I think it will be useful to take a more in-depth look at the relationship between Shirow's manga and Oshii's version, which, as the first adaptation of Ghost in the Shell, set the tone for everything that was to come afterward.

As is the case with almost all projects like this, the decision to adapt Ghost in the Shell didn't originate with the man who would become the film's director. As much as we like to think that directors have control over their body of work, often it is far more complicated than that, with large companies and producers dictating what gets made. In the case of Ghost in the Shell, it was Bandai who came to Oshii, with money that had in part come from an international coproduction deal with Manga Entertainment. Even if Oshii wasn't thinking about the distribution and marketing of the film beyond a domestic Japanese market, certainly folks higher up in the production food chain had such aspirations in mind. Perhaps it is for this reason in part that Ghost in the Shell is probably the film that best melds Oshii's art house and action impulses.

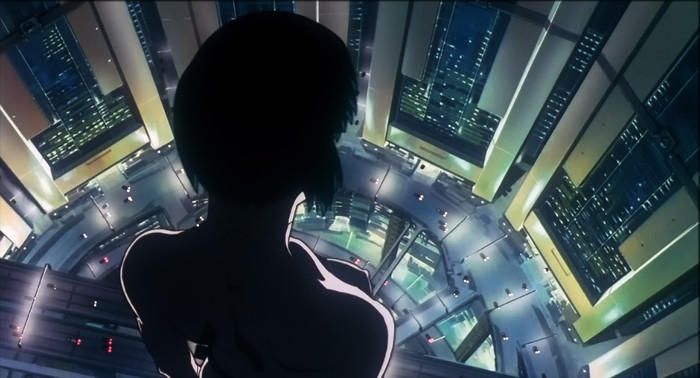

Shirow's original manga begins with an assassination of a foreign government official by a secretive cyborg operative named Major Motoko Kusanagi. In the story, public security officers storm a clandestine meeting in a high-rise and threaten to arrest the official and his compatriots. However, their operation is cut short when Kusanagi shoots the official from outside the building. As Kusanagi makes her escape by plunging down the side of the skyscraper, her form begins to merge into the background thanks to her high-tech camouflage. It's a powerfully iconic scene, drawn by Shirow in glorious color (which makes it all the better to see the flying guts of the official when he explodes from Kusanagi's bullets). It had such an impact that Oshii took this scene as the opener of his film, and it has continued to be referenced in one way or another throughout the Ghost in the Shell franchise.

From there, the plot of the manga and Oshii's anime begin to diverge. Shirow next follows Kusanagi and her team on a raid of a orphan relief center that may be brainwashing and exploiting people, after which her Section 9 assault force is officially formed. From there, the Major and her crew track down a garbage man who is unwittingly hacking the cyberbrain of the interpreter of the foreign minister, find the culprits behind a series of robots who have been attacking their owners, investigate an old Soviet submarine base on Etorofu being used for possibly nefarious purposes by a Japanese electronics company, fight with terrorists and crime syndicates, and deal with a government-created program called the Puppeteer that has seemingly turned sentient. In the end, Kusanagi (with the help of her Section 9 partner Batou) fakes her own death to try to escape both domestic public security and foreign intelligence agencies. Kusanagi in then approached by the Puppeteer and merges her consciousness with it in order to forge a new path into the cyber world. Shirow also includes a couple of shorter chapters that focus on the AI tanks called fuchikomas that Section 9 uses. These tanks are rather naive and used for comic relief, but also contribute to the ongoing discussion of the nature of life in the new digital age.

As you might be able to tell from this description, the Ghost in the Shell manga is very episodic. The closest thing to a narrative thread running through it is the story of the Puppeteer, and even this rogue digital lifeform doesn't appear until more than halfway through the book, initially appearing in chapter 9 and then once more in the final chapter. Most of the Puppeteer's arc is taken care of in the first chapter in which it appears. It only makes a sudden appearance at the end of the manga to merge functions with Kusanagi in what can very appropriately be called a deus ex machina resolution as a way of finally freeing her from her commitments to Section 9.

Oshii and scriptwriter Kazunori Ito took Shirow's episodic elements and wove them into a whole that would work better as a single coherent film. They used the Puppeteer saga as the backbone of their story, and incorporated the quandary of this new advanced program throughout. (The English translation of the manga uses Puppeteer, whereas the subtitles for the film usually use Puppet Master. Both are equally correct, and I often prefer to go back and forth, depending on which format I'm talking about.) Therefore, in the first scene of the assassination, the officials are made to discuss the problem of the Puppet Master before Kusanagi makes her violent entrance. Oshii and Ito then incorporate the episode of the hacking of the minister's translator, only this time the final culprit is the Puppet Master. (In the manga, it was entirely unrelated.) In order to simplify things, Oshii and Ito cut down on the international politics present in the original, only vaguely gesturing at the relations outside their country's borders. Many aspects of the chapter that focuses on the Puppet Master play out in the anime much as they do in the manga. Structurally, one of the biggest differences is that instead of a narrative break between when the Puppeteer tries to seek asylum with Section 9 and Kusanagi's final merger with it, the film lets the events play out unimpeded.

Not only did Oshii and Ito take Shirow's original narrative and make it less fragmented, they also significantly changed the overall tone for the film version. Gone are the comic relief fuchikoma sidekicks, as well as the superdeformed art that Shirow would occasionally use for levity, particularly in the closing panels of his chapters. Hiroyuki Okiura's character designs were far less cute and more realistic, even at the expense of being less "cool." For example, when we first see her in the manga, Kusanagi is rocking a large mane of blue hair and a cyberpunk wraparound visor that serves some undeclared function. The film's Kusanagi is far more severe, both in appearance and her personality. While the manga is swirling with humor, anger, and sometimes even love among the members of Section 9, the film's characters demonstrate far less emotion. This makes the film more subtly poignant in some aspects - for example, we can tell that Batou has feelings for Kusanagi by some of the little things he does in his interactions with her - but potentially less accessible to an audience expecting emotional involvement. This austerity is helped along by Kenji Kawai's haunting score that highlights some of the themes of the film. In a world where the organic and the machine is being blurred, Kawai's music amplifies the human voice through a choir and a rhythm that sounds as if it could belong to an ancient ritual.

In addition to Oshii, Ito, Okiura (who also did key animation, supervision, and layouts, and would go on to direct the film Jin-Roh from a script that Oshii wrote), and Kawai, the Ghost in the Shell anime boasted an astounding list of collaborators. The art director was Hiromasa Ogura, whose lovingly detailed work (he was also worked on the background art) really brought the world of Ghost in the Shell to life in a realistic way. Some anime fans may recognize Ogura in the fictionalized character of Ookura in Shirobako. Toshihiko Nishikubo had been the animation director on Oshii's Patlabor z2, and he reprised his role with this film. One of his later directorial credits would be Musashi: The Dream of the Last Samurai, an animated experimental documentary penned by Oshii about the famous swordsman Miyamoto Musashi. Shoji Kawamori of Macross fame did some of the mechanical designs, and the amazingly talented animator Mitsuo Iso not only worked on key animation, he was given a prominent credit for weapon design. Iso would later take some of the technological themes present in Ghost in the Shell in a different direction with his television series Dennou Coil.

Another noted collaborator was photographer Haruhiko Higami, who continues to work with Oshii on his many projects. Higami often works in the early stages of a production while scouting locations that will later be used in the film. This attention to detail highlights another difference between the manga and the anime film - the use of location and the role the city plays. Shirow's Ghost in the Shell takes place in a futuristic Japan, filled with newly futuristic skyscrapers, utilitarian industrial buildings, and urban decay. Yet it's also a place where Kusanagi's squad can be found relaxing before a job on the grounds of a peaceful temple. In other words, Shirow just took the landscape of Japan he was seeing and extrapolated it into a plausible future. Oshii, on the other hand, wanted to go in a different direction, and modeled much of the city in the film on contemporary Hong Kong. He was looking for a setting whose visual impact would mirror the density of the information flowing through the data networks that Section 9 accessed. So Hong Kong became the model of the new world of information that Kusanagi inhabits, taking in the sights as she cruises along and questions her humanity and the nature of life.

All of these things combine to give the film a different feel from the manga. Oshii added his own unique touches as well, such as a fight scene in water that was inspired by the video game Virtua Fighter. (From the trailers, it looks like the live-action film adapts this scene, which was not directly from the manga. This makes it rather meta, in a way - it is a CG-assisted scene that adapts an animated film that adapts a video game that adapted real martial arts moves.) He also made the characters more introspective, which brings a whole new depth to Kusanagi's character. Much has been written on the mind / body duality of Kusanagi in both popular works as well as academic articles. I haven't run the numbers, but I would not be surprised if she was the most-analyzed character in Japanese animation. This makes sense, since her problems are both universal and specific. Many of us can relate to her in some way - we can appreciate what it's like to be looking for freedom, to try to find ways out of the systems that surround and constrain us. This is one of the things that makes the Kusanagi of the film so fascinating - while she may not be as relatable to an audience on an emotional level, her drive to understand and surpass herself makes her an excellent role model for the 21st century.

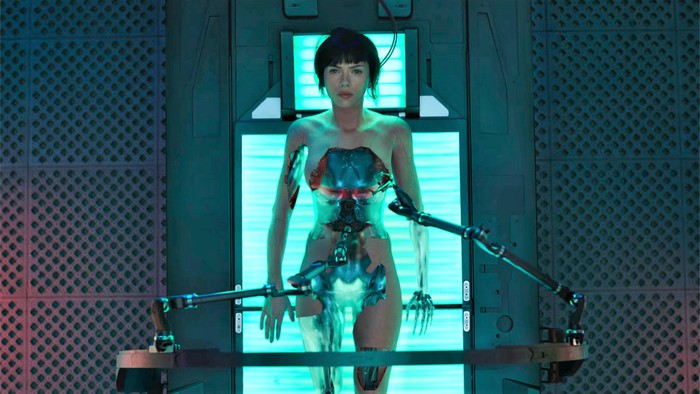

I am unsure whether any of these greater themes will find their way into the live-action Hollywood version. Scarlett Johansson's leading role certainly seems to be taking its cues from Oshii's more somber and intellectual Kusanagi rather than Shirow's partying, joking, loving version. If this is indeed the case, it seems somewhat ironic that a character whose goals are self-knowledge and questing for freedom finds herself enmeshed in a racialized Hollywood system where a woman of Asian descent can't play the main role in a big-budget film like this. Many have argued that the live-action Ghost in the Shell would not have the same shot at success with someone else as the Major, because there is not an Asian lead in Hollywood today with the same kind of draw as Scarlett Johansson. Although this might have some truth to it in the cynical and depressing world of Hollywood movie financing, it is indicative of much larger issues beyond the casting of a single film. Money and race are certainly aspects of control, manifestations of an even more encompassing system whose grasp we should be looking to evade if we are truly interested behaving like Kusanagi and surpassing our limitations. In Oshii's anime, Kusanagi realizes that she is only able to escape due to the change that she undergoes when she merges with the Puppet Master. For its part, the Puppet Master wants to merge with Kusanagi because it is after diversity, and knows that a stultifying sameness poses an existential threat. As the Puppet Master famously says to Kusanagi, "Your desire to remain as you are is what ultimately limits you." Although this is certainly true on a personal level, the same can be said of societies as well.

discuss this in the forum (22 posts) |