The Mike Toole Show

YAS Hands

by Michael Toole,

A couple of times a year, I'll go to a convention and run a few panel presentations—usually jaunts through the career of a certain artist or studio, explorations of a particular genre, or one of my mainstays, Dubs that Time Forgot. A few of these have even been featured here on ANN, and the gist is pretty simple—I dig up old English-dubbed anime, be it forgotten theatrical features, orphaned pilot films, obscure TV airings that never made it to home video, or stuff that didn't make it to North America period, and show ‘em to people. Afterwards, at least one person will always ask me why I do this. The thing is, I do it out of a desire to preserve this old material (much of it has never made it to DVD and never will), but also because of the simple thrill of discovery, of finding something completely new and unexpected.

It was with this thrill of discovery in mind that I set out to unearth a dub of White Fang, a 1982 TV movie produced by Sunrise. The film's typical of its day, a period that also produced anime TV movies of great western novels like Daddy Long-Legs, Les Misérables, and Call of the Wild. All three of the above were dubbed in English, so it seemed only natural to me that White Fang must've gotten that treatment too. I was particularly keen to find White Fang, because it featured character designs by one of the great masters of the medium, Yoshikazu Yasuhiko. I didn't find what I was looking for, but I found something else that was totally unexpected. Before I detail that, though, let's talk about the illustrious Mr Yasuhiko, or as he calls himself, YAS.

YAS has an origin story that similar to that of peers like Osamu Dezaki and Rintarō—he dropped out of school to work as an animator, getting his training in at Mushi Production in 1970. He'd work on the studio's seminal shoujo TV series Wandering Sun before Mushi faceplanted into bankruptcy. Yasuhiko was part of the Nishizaki-led exodus to Office Academy, where he also put his mark on Space Battleship Yamato as a storyboard artist. In the meantime, Yasuhiko put in work as an animator for a series called Zero Tester (he's listed as the character designer in the ANNCyclopedia at the moment, but those duties were actually handled by Munehiro Minowa), a merry Thunderbirds takeoff by another new studio formed by Mushi refugees, this one called Sunrise. Zero Tester was only Sunrise's second animated series, but it would prove pivotal—not only did it provide valuable experience for future heroes like Ryōsuke Takahashi and Sōji Yoshikawa, it also showcased the design and illustration work of Crystal Art Studio, a collective of artists who later changed their company name to Studio Nue and went on to become hugely influential in their own right.

It was in 1975 that Yoshikazu Yasuhiko really started to flex his creative muscles. He drew the characters for breakout hit Brave Reideen, a show that saw him fall back in with his Wandering Sun director, Yoshiyuki Tomino. He had a hand in designing the show's titular robot, the first Japanese cartoon robot to transform into a vehicle. Later that same year, he helmed the prehistoric children's comedy/adventure Kum Kum; not only did he create the scenario, he drew the characters and acted as animation director. Chief director on that series was Rintarō, in the midst of his own creative boom. Two fun Kum Kum facts: number one, soccer superstar and World Cup runner-up Sergio Aguero takes his nickname, “Kun,” from Kum Kum. Number two? Kum Kum was dubbed in English and shown on TV… in Australia.

inding this dub, like I mentioned above, elicited an amazing feeling of discovery. My friend and Dubs That Time Forgot originator Dave Merrill tracked down some episodes, which were dumped straight from slightly-fuzzy 8mm film and uploaded by some mysterious benefactor or another. The episode credits bore Paramount's name, but they were actually dubbed in Australia—audio director Phil Judd was a stalwart at Hanna Barbera's Australian studio, and the cast included the regulars from Yoram Gross's Dot and the Kangaroo films, including a young Keith Scott, who'd go on, some 20 years later, to become the official voice of Bullwinkle. I don't think this dub officially reached the United States, in terms of broadcast, but I've got pals in Australia who remember watching it on the tube. Now, of course, you can comb the internet for the Kum Kum dub and enjoy it in all its fuzzy glory.

But enough about kooky old dubs for now. Kum Kum, despite being a goofy comedy for little kids, looked kinda incredible. YAS's character designs were becoming remarkably strong and distinct, and under his direction, the show's drawings almost always looked good. His peers have pointed out how mind-bogglingly sure his technique is—he presses hard into the paper when he draws, seldom making any mistakes, and in his manga he frequently employs bamboo paintbrushes for finishing instead of pens. But in the mid-70s, he hadn't quite established himself as a manga powerhouse – he was still busy playing trendsetter, teaming up once again with Yoshiyuki Tomino for the compellingly violent, grim Zambot 3. He also helped out the great Yasuji Mori with the character designs for The Little Prince, which, if you're of a certain age, you might remember watching on Nickelodeon. I hadn't thought of that show in years (yes I own the entire thing on DVD, why do you ask?)—you can tell from looking that YAS was involved, but I was kind of surprised to look at the credits and see that the animation production was provided by the merry trashmen at Knack Productions, who are mostly known for their blazingly weird failures, like Charge Man Ken and Astroganger. But Knack had a couple of solid hits, like the influential shoujo volleyball series Attacker You!, and they acquit themselves well for what turns out to be a puzzlingly expansive redux of Antoine de St. Exupéry's touching fable.

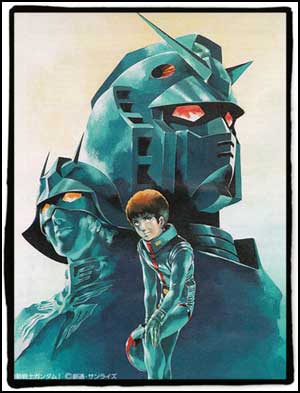

Then YAS got called up by his buddy Tomino, and what you're looking at above happened. In interviews, Tomino has repeatedly pointed out that Yasuhiko is an artist that he'll nearly always call first when he gets a new project, only deferring to others when he's not available. (The same goes for Gundam’s mechanical designer, Kunio Ōkawara.) Yasuhiko would once again prove to be a reliable collaborator, staying with the Gundam franchise for six years, and only departing when Zeta Gundam wrapped. He'd later climb back aboard for the fascinating disaster that was Gundam F-91, not to mention the generally excellent Gundam Unicorn. But YAS defined the look of Gundam’s characters, and by extension the look of SF anime characters in the 80s in general. Still, his days as a top creator lay ahead of him.

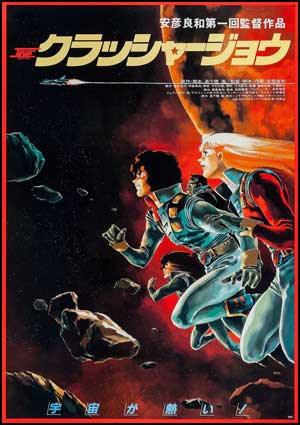

I say this because, when he drew the characters for Mobile Suit Gundam, fans still hadn't yet experienced any projects that were his in a way that his earlier collaborations hadn't been. There'd be a taste of that in his first long-form manga, the lavishly illustrated Arion, which debuted in 1979. But he'd make a much more dramatic impact in 1983, helming the theatrical film Crusher Joe. With Crusher Joe, YAS reunited with his old Studio Nue buddies; scribe Haruka Takachiho, who wrote the novels that the film was based on, had enlisted YAS to draw the illustrations for one of his earlier novels, The Great Adventures of the Dirty Pair. The pair of men teamed up to write a screenplay based on Takachiho's book. While the young Shōji Kawamori handled mecha design the film boasted an all-star brigade of guest designers, from Akira Toriyama and Keiko Takemiya to Yumiko Igarashi and Shinji Wada. Meanwhile, YAS directed the film. And drew some of the storyboards. Also, he wrote the script. He designed the main characters, of course. Oh, and he was chief animation director, as well. Yeah, he did like five or six different jobs, on a sweeping, ambitious SF adventure flick.

Anime is very often driven by auteurs, men and women who easily handle multiple production jobs, but what Yasuhiko Yoshikazu took on with Crusher Joe stood apart even then. The resulting film, while benefiting from the hard work of Takachiho, Kawamori, and the rest of the crew, exhudes YAS's aesthetic—refined character designs, fluid action, and dazzlingly detailed backgrounds and settings—like nothing prior to it. It's a film that still holds up wonderfully today, such that it kind of pisses me off that, like so many great anime films it's now out of print. I'm particularly fond of the titular protagonist—in an era that brought us callow spacefaring heroes like Luke Skywalker and the O.G. Battlestar Galactica crew, Crusher Joe himself is compellingly ruthless. In the movie's climactic showdown with a massive fleet of space pirates, Joe doesn't screw up his courage, stick his chin out, and belt out a quip like “Hold on to your hats, people!” Instead, when the pirate fleet—which vastly outnumbers his small crew's single ship—fails to surrender, his face contorts in fury, and he hisses “You just made a big mistake!” This leads into an extended space dogfight where the increasingly ragged Minerva, Joe's ship, repeatedly gets the better of huge, ponderous capital ships. It's fabulous, like watching the Red Baron wipe out a fleet of B-52s.

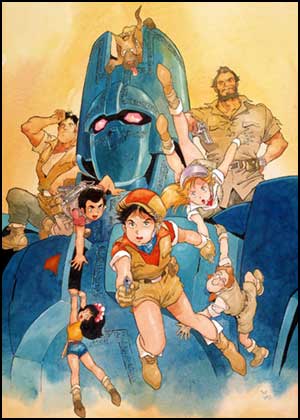

1984 would bring on Giant Gorg, a Sunrise TV series that boasted YAS's character designs. And storyboards. And animation direction, and chief direction, and it wouldn't surprise me if he helped Masaki Tsuji and Yumiko Tsukamoto on the scripts. Oh, and obviously, he created the series, as well. His touch doesn't hold up quite as well over a 26-episode TV series—Gorg does look wonderful, with a fantastic giant robot, fun heroes (one of which looks weirdly like Woody Allen), and a great big old Scooby Doo ripoff of a dog. (Fortunately, this dog, Argos, doesn't talk.) Each episode ends with a cliffhanger and the charming Engrish “TUNE IN TO THE NEXT: The same GORG time, the same GORG channel.” But the series is filled out with cartoonishly unthreatening villains and rivals—for a series about a race to connect with an alien superweapon, it seems weirdly low-stakes at times. Still, it's a beautiful show that benefits from its creator's touch. We almost got Giant Gorg from Bandai Entertainment back in the day, but an issue with the master tapes that Sunrise provided kept it from reaching store shelves.

Remember a few paragraphs ago, when I mentioned Yasuhiko's big debut manga, Arion? He eventually turned that into a feature film, in 1986. Yes, he directed it, and co-wrote the film's screenplay, and drew the characters, directed the animation, blah blah blah. While the film's visual and auditory splendor is undeniable (hey, it's Ghibli's Joe Hisaishi as maestro!), it's kind of a messy story, a free, diffuse adaptation of Greek mythology starring the super-powered son of the rebellious Prometheus. Still, when the animation kicks into high gear, it's incredibly compelling; Arion’s got peaks and valleys, but its highs are really high. So overall, Arion is a beautiful film, well-animated, and somewhat incoherent. It gets kind of hilariously loose with its mythmaking, reshaping the Arion of Greek myth, which is, I shit you not, a talking horse, as a fiery and smart young man. The three-way power struggle between Zeus and his brothers Hades and Poseidon is populated with all sorts of random gods—Athena here, Ares there—and many of ‘em end up dead. But it's full of action and eye-popping animation, and given that, it kind of amazes me that there's never been an English dub; something like this would've fit in beautifully with the old Streamline catalog, and lest we forget, good old Streamline did raid the Sunrise vaults for the Dirty Pair film and OVAs.

YAS followed Arion with The Song of Wind and Trees, a 1987 OVA based on the manga by Keiko Takemiya. Just as he'd shaped the look of SF and mecha anime characters before, the artist here creates one of the definitive shounen-ai animation works, right up there with Mad House's splendid Door Into Summer film. The OVA, a subtle piece about a pair of boarding school outcasts finding solace with each other, is vibrant and beautiful. It's funny, back before shounen-ai and yaoi were well-known in western fandom (it's hard to believe, but stuff like this used to be very hard to find!), you'd usually get this OVA on a tape with the much more lurid, adult Bronze: Zetsu-Ai OVA. Bronze is still pretty compelling stuff, but the effect is kind of like running Breakfast at Tiffany's back to back with Animal House.

The last of Yoshikazu Yasuhiko's big, personal animation projects is 1989's Venus Wars, based on his manga of the same name. Much like Arion, Venus Wars is an intensely beautiful movie that struggles with its story. But unlike Arion, it doesn't really matter—the tangled plot, about a civil war on Venus and the disaffected youth that rebel against both sides, just kinda fades into the background in the face of particularly magnetic characters and some absolutely amazing action sequences. Way back in 2008, Justin wrote about this movie, and reached the same conclusions I did—Venus Wars is a film that simply overcomes and surpasses its obvious narrative flaws with arresting visuals. It's like watching a really good action movie with a forgettable plot; sometimes, that's just what you needed. Happily, since Justin's written about it, Venus Wars has come back into print. It's one of those great 80s anime films that is dangerous to watch, because even a brief clip will make you want to finish the disc.

YAS had some other projects—I'm fond of Super Atragon, a sequel to the live-action SF film Atragon about a flying submarine with a drill on the front, which features the artist joining up with a bunch of the Giant Robo pit crew to tell a thrilling retro-SF adventure. We've also been fortunate to get a bit of his manga here—years ago Comics One published the three-volume Joan, his biographical Joan of Arc story. You can still get the whole set for $20 or $30, and it's kinda worth it just for the artwork. Sadly, a promised English release of Yasuhiko's Jesus, a biography of the son of God himself, never materialized. Gundam: The Origin, a splendid return to the original Universal Century war, is in North American bookstores now, keeping our interest piqued while we wait to see how the animated version of Gundam: The Origin turns out. (Of course Yoshikazu Yasuhiko is providing character designs for it! Don't be absurd.)

I'll close this recounting of one of anime's best and most influential character artists and animators with that White Fang anecdote I promised. I never did find a dub of the White Fang that YAS worked on—there's a raw Japanese rip on YouTube (the TV movie doesn't seem to have made it to DVD, so stuff like this is all we've got), but that's about all I turned up. But I still did find a dub of White Fang! It was just a different White Fang, one from 1990. As I began watching, strange details emerged; sure, the characters called each other names like Weedon Scott and Beauty Smith, but they were clearly not in the correct time period, and the setting and narrative bore little in common with Jack London's novel. I soon discovered that this “White Fang” I was watching was actually a Group TAC film based on Mel Ellis's novel Flight of the White Wolf!

The reason I figured this out relatively quickly is because I actually read the book, which was written for YA audiences and released in the 70s. It's a tidy little read about a kid rescuing his pet wolfdog from vengeful authorities (the wolf, Gray, had killed an aggressive show dog, so hunters were sent out to kill him) and hiking across the Minnesota forests and prairies to deliver the animal to a wildlife sanctuary. It's the perfect thing when you're a schoolkid who likes animals, and TAC do a good job recreating the suspense of the story and the beauty of the wilderness that the boy, Russell, must traverse to save his buddy. Interestingly, the entire soundtrack is made up of Antonín Dvořák's Serenade for Strings. You can hang that decision on TAC head Atsumi Tashiro, who handled music and sound design for the film. It's an interesting idea, and the music complements the story well.

The dub is kind of amusing, because they doggedly try to stick to the idea that this is some sort of version of White Fang, renaming Gray the wolf “Fang” (why would you name a white wolf Gray, anyway?) and referring to Russ as “Weedon Jr.” London's White Fang was set in the late 1800s and Flight of the White Wolf clearly takes place closer to the present (there's even an amusing sequence of Russ raiding a convenience store for supplies, complete with off-kilter candy names and newspaper headlines). Ultimately we're left with a damn decent animated family movie, in spite of the bizarre adaptation; not surprisingly, White Wolf never made it to DVD, like so many interesting 80s and 90s anime films.

Flight of the White Wolf perfectly exemplifies why I continue to seek out weird old dubs. Every time I go looking for something like the Sunrise White Fang, I may not find the target, but I'll still unearth something worth savoring and hanging on to. I bemoan the fact that there doesn't seem to be a dub of YAS's White Fang (why, when so many others were dubbed, was this one passed over?), but the search continues. After all, Yoshikazu Yasuhiko also contributed character designs to Combattler V, one of Tadao Nagahama's famous “robot romance” shows. For years, I've heard whispers of an English dub of Combattler V, broadcast in the Philippines and elsewhere in east Asia. Now, all I have to do is find it!

discuss this in the forum (26 posts) |