Make Everything E.X.P.L.O.D.E. — The Other Works of Akira's Katsuhiro Otomo in English

by Kevin Cormack,

For Western anime fans of a certain age, Katsuhiro Otomo's 1988 cinematic masterpiece Akira was the gateway drug into Japanese animation's wild and exotic world. Growing up in late 1980s Scotland, I was exposed to kid's TV shows that, at the time, I had no idea were Japanese — especially my three favorites, Battle of the Planets, Mysterious Cities of Gold, and Ulysses 31.

Then BBC2 broadcast Akira late at night on January 8th, 1994 at 23:05, and I got permission from my parents to stay up late to watch this much-hyped movie. I was transfixed by the amazingly detailed visuals, brutal violence, and flawed but fascinating characters, and somewhat discombobulated by the complex plot. I needed to find out more.

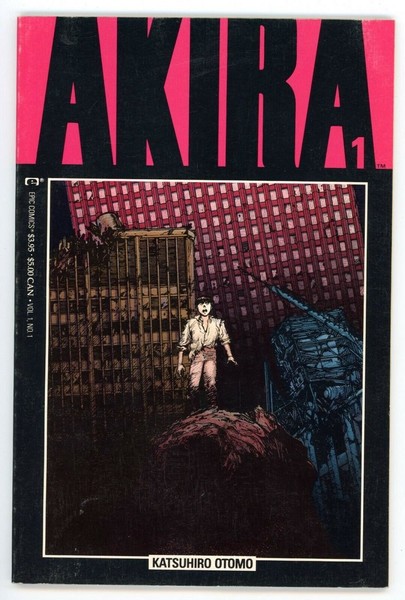

At that time, Dark Horse Comics' short-lived UK branch produced a monthly magazine — Manga Mania — that was part manga anthology, part news and reviews. Think of it as the UK's equivalent of Viz's Animerica, but better. Almost half of Manga Mania's 128-page count comprised reprints of Marvel's Epic Comics' 38-issue English adaptation of Akira. While the U.S. editions were painstakingly, digitally colored by the Harvey and Eisner award-winning Steve Oliff (Otomo's personal choice) in an attempt to entice American readers, the UK editions mostly reverted to the original black-and-white, showcasing Otomo's incredibly detailed pen and ink draughtsmanship. Every month I excitedly anticipated the next chapter and was henceforth doomed to lifelong anime and manga infatuation.

In its original Japanese form, Akira ran for 120 chapters between 1982 and 1990 (similar to Miyazaki's 1984 Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, Akira's movie was released long before its source manga concluded). These chapters were released in the U.S. three at a time, which was completed in 1996. Due to Akira's success, 1990s manga publishers looked to capitalize on this by releasing some of his earlier work. The aborted 1979 serial Fireball (all meager fifty pages of it) was collected in the UK by Mandarin Books' short-lived Equinox Manga imprint in the anthology Memories.

Memories contains fourteen of Otomo's early short stories; sadly, it has long been out of print, and any available copies go for eye-watering prices online. As a poor teenager, I borrowed this from my local library. One of my biggest regrets is that I never got my own copy. Of note to Otomo's anime fans, the anthology contains the short manga Memories, later adapted into Magnetic Rose, a segment of the 1995 anthology anime also titled Memories. Farewell to Arms was (much) later adapted as A Farewell to Weapons, part of the 2013 Blu-ray/PS3 game hybrid anthology Short Peace. Both stories were published separately in the U.S. as 32-page one-shots by Epic Comics, whereas the other short stories are available in English only in this rare UK volume.

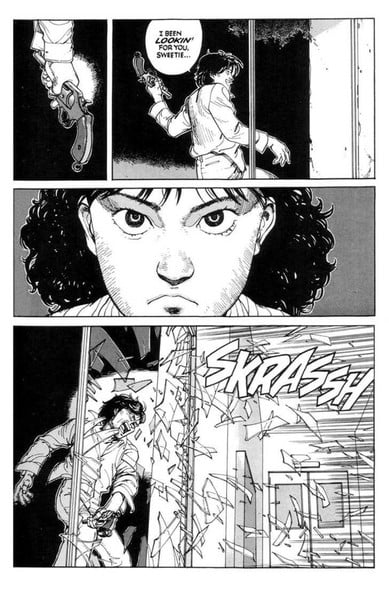

My favorite Otomo manga is the single-volume Domu (A Child's Dream) from 1981, which directly precedes Akira in terms of theme and content. Adapted twice into English contemporaneously, it was released in the U.S. by Dark Horse in three parts in an odd mini-prestige square-bound format. In contrast, in the UK, like Memories, it was released by Mandarin Books, along with Gon (by Masashi Tanaka) and the Steve Oliff-colourized Akira Volume 1. Dark Horse's translation and lettering work are much smoother, but both versions are long out of print.

Domu is set in a large Japanese apartment block and follows a young girl with emerging psychic abilities battling a mischievous and cruel old man who murders people with his powers. It's a masterclass in tension, atmosphere, and wordless communication, with a (literally) arresting ending. Otomo's eye for painstaking architectural detail takes shape here, lending his mundane apartment block setting a concrete sense of place, later perfected in Akira's Neo Tokyo. Domu is worth seeking out. Guillermo Del Toro acquired the movie rights years ago but failed to produce anything.

In the late 1990s, Dark Horse began publishing the seven-volume The Legend of Mother Sarah, a post-apocalyptic road trip manga that owes a lot to Mad Max, but this time features the formidable yet maternal Sarah who searches the ruined world for her missing children, fighting fascists and other evil-doers along the way. Dark Horse published only the first three story arcs, leaving the story incomplete. Only the first volume was collected in trade paperback format, with the rest available in single floppy issue form. Although written by Otomo, the art is by Takumi Nagayasu, whose art style is heavily Otomo-influenced. Dark Horse flubbed when publishing the collected edition, neglecting to credit Nagayasu on the cover. My wife particularly loved this manga and was heartbroken at its English cancellation.

Following Akira, Mother Sarah, and 2001's children's picture book Hipira (also translated by Dark Horse but now out of print. The anime adaptation streams on TubiTV), Otomo mostly left the world of manga behind to focus on his cinematic career. His first anime credit was as a character designer for director Rintaro's infamous Harmagedon (1983), any Western release of which is long out of print. Before his breakthrough as Akira's director in 1988, he directed segments of two prominent anime anthologies: Robot Carnival and Neo Tokyo, in 1987.

Otomo's contributions to Robot Carnival are the anarchic opening and closing segments, linked by the presence of the titular Robot Carnival, a tractor-treaded mobile monstrosity and traveling war machine filled with fairground-style automatons that bring death and destruction with a painted-on-smile to a desert village of terrified people. As his true directorial debut, Otomo introduces his twisted form of comedic nihilism to the world and his repeated penchant for beautiful, outrageous destruction.

Neo Tokyo was originally titled Meikyu Monogatari (Labyrinth Tales), or Manie-Manie in Japan, but in the U.S. it was renamed to cash in on the success of Akira. It's a poorly chosen title that reflects little on its contents. Otomo's contribution is the darkly humorous "Construction Cancellation Order," a satire on the inflexibility of Japanese corporations. A hapless middle manager is sent to decommission an autonomous AI-run construction plant deep in the South American rainforest. Unfortunately, the order to “de-commission” completely contradicts the psychotic robot overseer's primary objective to continue work at all costs. Said manager is subjected to an increasingly terrifying ordeal, resulting in the hint of (off-screen) cathartic destruction following the tale's conclusion. It's a fascinating, brief, and concentrated dose of Otomo's exasperated worldview that will ring true for anyone failing to effect change while mired in corporate bureaucracy.

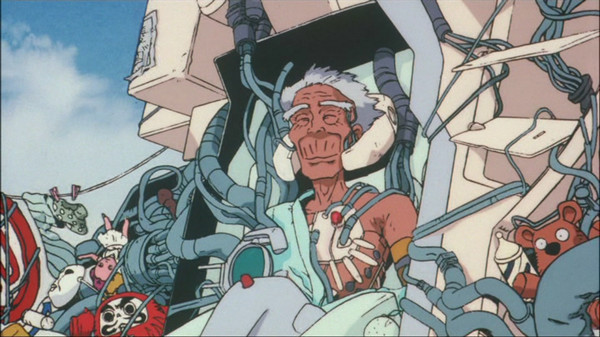

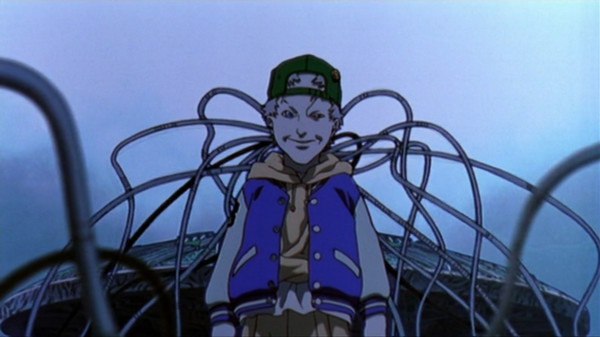

Following his overwhelming success with 1988's Akira, where he directed the adaptation of his own (at the time unfinished) manga, Otomo's next credit was as a screenwriter for 1991's Roujin Z, another satirical work, this time directed by Hiroyuki Kitakubo. Roujin Z is an increasingly timely fable concerning the time bomb facing all post-industrial developed countries: demographic collapse. With the reduced birth rate, elderly people will eventually outnumber working people, and there will be a care crisis.

In Otomo's version of future Japan, the government, military, and healthcare providers have collaborated to develop the completely autonomous mechanized Z-001 bed-care system for the elderly and infirm. It's a humorous but alarming concept — the nominal “main character,” Mr. Takazawa, is strapped into this machine, force-fed, bathed, exercised, and invasively monitored, all without his consent. The corrupt corporate stooges running the trial repeatedly comment on Mr. Takazawa being the least valuable part of the system. Thankfully he has a good nurse in the young Haruko who objects to the dehumanizing Z-001 system, though she can't prevent it from going berserk.

Roujin Z reflects Otomo's singular obsessions, from the dark humor to the insane mecha battles (Mr. Takazawa and his AI bed against a military death machine), to the very Akira-like metal tentacles and out-of-control monster expansion in the overblown action climax. Obviously, there are explosions; Otomo loves to build things up like a kid with a tower of blocks, only to bring them tumbling down, cackling maniacally as he does so.

With 1995's Memories, an anthology of three Otomo short manga adaptations, he himself directs the third segment, the visually unique Cannon Fodder. Again, this is a satirical look at a society organized entirely around the concept of endless, self-perpetuating war. Otomo's directorial work here is outstanding ; it's essentially all one long take, a day in the life of a family — mother, father, son — all cogs in their society's enormous war machine. Some of Otomo's camera tricks and perspective changes still baffle today in their creativity and spectacle.

Cannon Fodder isn't laugh-out-loud funny, but the exaggerated character designs and Soviet-esque settings sit between gently humorous and genuinely discomforting. There's a kind of deep malaise, of hopelessness and emptiness evoked by this short, that's more than a little reminiscent of Orwell's 1984, except instead of a boot stamping down on a human face for all eternity, it's forever in the sights of a massive gun.

Memories' other two (non-Otomo-directed) segments are well worth watching: the spooky and surreal Magnetic Rose features an early screenwriting credit from Satoshi Kon, and Stink Bomb—my favorite segment of the whole film—is another hilarious, darkly funny military satire.

Between 1994 and 2004, Otomo focused on producing his next magnum opus: Steamboy, the incredibly ambitious, much-delayed, over-hyped successor to Akira. However, he also contributed to creating 1998's Spriggan as the nebulously-titled “general supervisor.” It's very unclear from any official sources what Otomo actually did here. Still, his fingerprints are all over it, especially in terms of the climactic action sequence where, you guessed it, everything explodes. Spriggan as a movie fails to measure up to Otomo's previous work; it's a cookie-cutter shonen manga adaptation that's emotionally empty and intellectually dull. However, the action is fluidly animated and exciting, so it isn't a total washout.

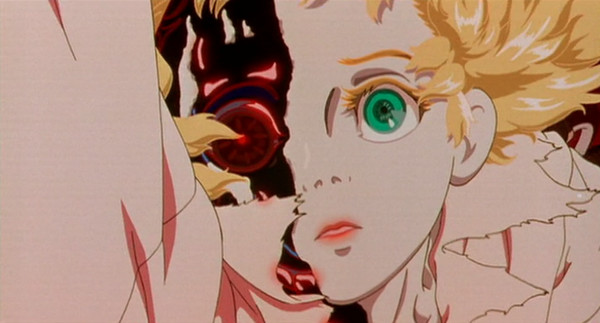

2001's Metropolis reunited Otomo, as screenwriter, with director Rintaro, adapting a 1949 Osamu Tezuka manga. Tezuka was inspired to write his story by a single still image from Fritz Lang's 1927 silent movie of the same name, but his manga bore little resemblance to the film. Otomo attempted to marry two completely different sources for his script and more or less succeeded.

Metropolis is a gorgeous movie, easily one of Rintaro's best. It's authentic to Tezuka's character designs and fairly closely adheres to the shape of Tezuka's plot, if not in most of the details. With imagery evoking a 1920s-esque retro-SF future, few anime can rival Metropolis in terms of sheer beauty. Once again, Otomo spends time building a massive edifice — this time, the city of Metropolis' central Ziggurat, a clear reference to the biblical Tower of Babel, with multiple references to ancient Mesopotamian civilization in the script. The end sequence is a frankly stupendously animated sequence of extended destruction as the Ziggurat spectacularly explodes, a metaphor for man's hubris, brought low by his own creation (in this case, androids). Such themes Otomo returns to again and again, prominently with Akira, but also with Steamboy.

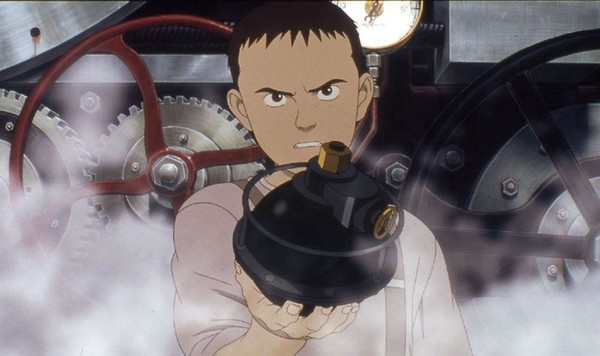

After ten years in extended production, Katsuhiro Otomo's second full-length directed movie Steamboy (2004) was released in a storm of publicity… then promptly forgotten. It wasn't even granted wide cinematic release in the U.S. by Sony Pictures, who butchered 21 whole minutes from the movie, opening it in a handful of arty cinemas, and only releasing the original version on disc as the hilariously-titled “Director's Cut” (well, yes, that was the version that Otomo was happy with until you chopped it to bits, Sony).

A completely different beast to Akira, Steamboy probably wasn't what anyone expected. Featuring no illegal drugs, psychic powers, or even monstrous flesh blobs, Steamboy is an action-packed, Victorian England-set, family-friendly steampunk adventure. And I love it. Once more, Otomo returns to his favorite theme of human hubris resulting in catastrophe and a hint of teenage rebellion. Otomo clearly has a strong dislike for rampant capitalism, for unchecked corporate exploitation.

Steamboy follows the 13-year-old Ray Steam and his fight to keep his grandfather's nuclear bomb-esque “steam ball” technology out of the hands of various suitors with untrustworthy intentions. The North American O'Hara Foundation's enormous metal “Steam Castle” is Steamboy's equivalent of Metropolis' Ziggurat. Its eventual destruction is a stunning but lengthy and exhausting action sequence that comprises most of the final third of the movie. It really is Otomo unleashed in what is probably the most obsessively detailed sequence of urban carnage ever set to animated film. I can almost imagine Otomo giggling, “More! More! More explosions!” for most of the entire decade he spent directing it.

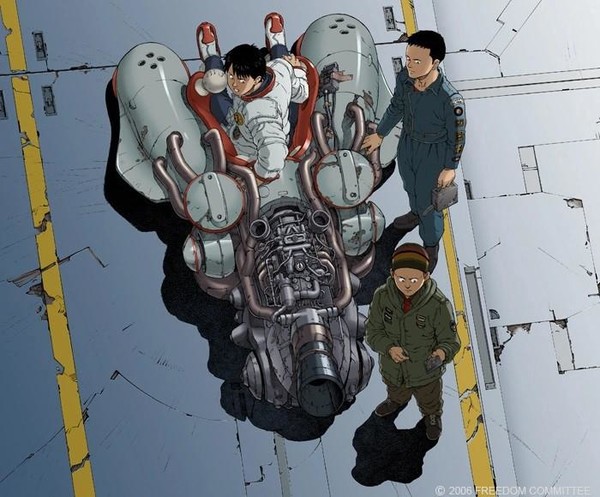

Following Steamboy, Otomo took a detour into live-action with the adaptation of the manga Mushishi (2006), which was also released in English, unlike his first live-action effort, 1991's World Apartment Horror. 2006 also brought the sci-fi OAV series Freedom Project, commissioned by food corporation Nissin to celebrate the 35th anniversary of their ubiquitous Cup Noodle. Otomo provided character and mecha designs, stamping the production with his unique style, but he was only involved in the pre-production stage.

Otomo's most recent animation work was the 2013 anthology Short Peace, which comprised four main segments and a PS3 game. Each anime segment was based on one of his very early manga shorts, and he directed Combustible, a story set in Edo period Japan. It has a fascinating horizontal scroll aesthetic, with characters like traditional wood-block prints brought to life. Although it starts sedately, as seems to be Otomo's repeated predilection, it progresses into a fiery conflagration that brings tragedy and destruction. Also notable is "A Farewell to Weapons" and its reprise of Otomo's comedic nihilism in a post-apocalyptic military setting.

It's been nine years since his last release, but Otomo is currently working with Bandai Namco Filmworks on his third full-length movie as director, Orbital Era. Not much is known about this project and the website that announced it has yet to update since 2019. If his past form is anything to go by, it could be another decade until the project is realized. Otomo also announced in 2019 that Akira would receive a TV anime, presumably to cover the entirety of the manga's story rather than the truncated version depicted in the movie. So far, we've heard nothing more about this either. I suspect we should trust in Otomo's perfectionism—eventually he'll have something incredible, beautiful, humorous, disturbing, and explosive to show us.

Kevin Cormack is a Scottish medical doctor, husband, father, and lifelong anime obsessive. He writes as Doctorkev elsewhere and appears regularly on The Official AniTAY Podcast. His accent is real

Disclosure: Kadokawa World Entertainment (KWE), a wholly owned subsidiary of Kadokawa Corporation, is the majority owner of Anime News Network, LLC. One or more of the companies mentioned in this article are part of the Kadokawa Group of Companies.

Disclosure: Bandai Namco Filmworks Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Bandai Namco Holdings Inc., is a non-controlling, minority shareholder in Anime News Network Inc.

discuss this in the forum (10 posts) |