Forum - View topicErrinundra's Beautiful Fighting Girl #133: Taiman Blues: Ladies' Chapter - Mayumi

|

Goto page Previous Next |

| Author | Message | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

yuna49

Posts: 3804 |

|

||

|

How is Chihayfuru not a "sports anime with a female lead?" Or are you saying that the team that made Wandering Sun should make such a show? I'm afraid Osamu Dezaki cannot be on-board; he died in 2011.

Shion no Ou might also qualify though there are other important plot themes like identifying the murderer of her parents. |

|||

|

|||

Alan45

Village Elder Village ElderPosts: 10012 Location: Virginia |

|

||

|

I think he intended to make a reference to 1973s Ace o Nerae! with Osamu Dezaki as series director. Hence the "Anyone for tennis" bit. I'm pretty sure that qualifies as a "sports anime with a female lead?"

|

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Yeah. I should be less cryptic.

Meant in a relatively immediate sense I was flagging two things. 1. Ashita no Joe + Sasurai no Taiyou »» Ace o Nerae!; and 2. An Ace o Nerae! review isn't far away. Unless something intervenes, it's fourth in line. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girls index

**** Beautiful Fighting Girl #8: Merumo Watari, aka... Marvellous Melmo

From atop the barricades Melmo leads the revolution against her bourgeois schoolteacher overlords. The revolt lasts until the boys get hungry. One is distracted by a notable trope of the anime: panchira. Synopsis: When the already widowed mother of nine-year old Melmo and her two younger brothers is herself killed after being struck by a car, she pleads with God to allow her children to grow up quickly as life will be difficult without parents. Be careful of what you wish for. Thanks to the divine intervention, Melmo is gifted a jar of red and blue lollies. One colour ages her ten years; the other makes her younger by ten. Swallow different combinations and all sorts of weird things can happen: she might be reduced to her original fertilised egg, from which, in a sort of Haekelian evolutionary twist, she can grow back into the animal of her choosing. Armed with the pills, Melmo does her best to bring up her brothers. Things get complicated when one of them turns into a frog with a gullet too narrow to swallow the necessary pills to make him human again. Amidst all her travails Melmo gets assistance and advice from the exiled Professor Waragarasu (aka Professor Nosehair) who provides regular lessons on natural history, evolution, ecology, mating, conception, pregnancy, birth and child rearing. Production: Premiere: 03 October 1971 Studio:Tezuka Productions Source material: the manga Fushigi na Melmo by Osamu Tezuka, published in Shogaku-Ichinensei from September 1970 to April 1972. Chief director: Tsunehito Nagaki Episode directors include Osamu Tezuka and Yoshiyuki Tomino, who also storyboarded the series. Note on the production: the series was re-aired in 1998 with new voice actors, music track, opening and closing credits and restored colours. I watched the "renewal" version. The current rights holders have made it available on Viki for those fortunate enough to live in regions where it can be accessed. Living in the provinces I had to watch it raw by other means. Happily the rights holders have also provided episode summaries via their website.

The two ages of Melmo. Her older body retains the child's mind, though you wouldn't know by that wink. Surprise, puzzlement and fear are characteristic expressions of the younger Melmo. Comments: In his survey of Beautiful Fighting Girls, Tamaki Saito treats the transforming girl as separate from the magical girl, though he admits to hybrid examples such as Sailor Moon. Oddly enough, he includes Secret Akko-chan as a magical girl, which seems inappropriate given that her mirror's power is to change her appearance in any way she chooses. That aside, and however one may label the series, Marvellous Melmo is not only the strangest magical/transforming girl anime I've ever seen, but it deliberately and forcefully introduces one of the genre's most enduring tropes: transformation from innocent, budding but powerless child to sexual, ripe, potent young woman. I use the words "budding" and "ripe" advisedly - Saito is a notable proponent of the theory that the term "moe" comes from the Japanese word for "budding". While Melmo pre-dates the term by over two decades, she is a moe prototype: her parents are dead; she is vulnerable; she elicits the viewer's sympathy; she is fertile in her older form. The ageing Professor Nosehair will protect and guide her. Where later magical girls display their sexuality in their outfits and in their romantic longings, Marvellous Melmo brings the biological processes front and centre. Each episode includes an educational sequence that, other than an absence of the mechanics of intercourse and the deployment of sometimes quaint metaphors, isn't afraid to depict the human body and the processes that will eventually lead to childbirth. Remember, this is a children's show. The anime ends with Melmo's marriage and the birth of her first child. In a sweet closing of the circle, the last two pills reveal to Melmo that the spirit of her mother inhabits her daughter. I'll provide an example of what the show does. In one episode, Melmo struggles to feed her infant brother Touch with milk formula. She reasons that, in her adult form she can breastfeed him, so swallows the requisite lollies. When she unable to lactate, Professor Nosehair gives her, and the viewers, a class on the role of hormones in lactation. Don't think, though, that the anime is either this dry (pun intended) or so narrow in its focus. Most episodes are adventures - it's amazing how often she is held hostage by villains - or hijinx around the use or misuse of the pills. The most dire example of the latter occurs when the older of Melmo's brothers turns himself into a frog - apparently ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny in this universe. He remains in this vulnerable form for much of the series, at one stage almost ending up on the menu in a restaurant. How he convinces a school principal to allow him to attend classes as a frog is a highlight, as is what happens when he does. (Why couldn't those other students keep their pet python in its cage?)

From the Nosehair lessons. Left: the successful sperm fertilises the waiting egg before a breaking wave of semen; and Right: an agitated child in the womb - his mother has been viewing modern art. Transormation is the characteristic trope of Marvellous Melmo. In his intruction to 100 Anime, Philip Brophy points out that, "characters in anime are not based on 'people we know', but on the possiblities of what people could be." He develops the idea more specifically in the article on the series.

Here's a neat idea: when we, as fans, identify with the beautiful fighting girl we are creatively participating in our own transformation, that we truly become ourselves by becoming something else. Hey! that's a dictum for life: develop self-awareness through watching anime. As otaku we participate in the creative processes contained within the anime we are watching. Saito will make a similar argument, albeit with his psychologist's emphasis on sex.

Clockwise from top left: Professor Nosehair lectures Melmo; Melmo's younger brothers Totoo (the frog) and Touch; The older Melmo's pendulous breasts and beckoning panty shots express her fecundity; and The Leaning Tower of Tokyo. Brophy also argues that the anime sympathetically portrays Melmo as a single mother in a society that prefers to render them invisible. While that is true, I'm not sure Tezuka is making a feminist argument. On the contrary, he seems to be limiting Melmo to her reproductive role, as evidenced by her eventual destination as wife and mother and by her desirability - I find her orange lips particularly beguiling (see image below). Her constant habit of transforming while dressed as a child (and a short child at that) provide ample opportunity to show off her adult form. I've said before - in my Princess Knight review - that Tezuka is a perv, but there is more going on here. One of the most important themes in his life's work is the notion of renewal in a world of both majesty and destruction. The image of the phoenix recurs throughout. It even has a role here: the pills that allow Melmo to transform are made in heaven by boiling down eggs laid by the phoenix. While Melmo's situation is treated sympathetically, if paternalistically, her ultimate role is to provide renewal. She is, metaphorically, a phoenix. The images are crisp and bright when compared with contemporary anime I've been watching, thanks no doubt to the "renewal" version on hand. Like Wandering Sun, though, the artwork and animation is basic in the extreme. The Tezuka humour is constantly evident, however the mostly episodic stories are, like the artwork, dull. I thought the voices actors seemed way too modern for the material until I learned they were recorded as recently as 1998. There is no choice but to accept that the script and the re-recorded incidental music remain faithful to the original. The version I watched had the OP and ED removed, but, what I imagine were the original OP and ED were provided separately. There's a moment 42 seconds into the OP where the rhythm stutters in a way that is near-perfectly mimicked in the ED of The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya. Anime ever renews itself by feeding on its own corpse. Rating: so-so. Fascinating overarching narrative, themes and subtext along with a restored version of the series can't compensate for ordinary visuals and mundane episodic plots. Marvellous Melmo is an essential anime In terms of the history of the artform and within the scope of the great project, and I highly recommend checking it out, but sitting through most of the episodes was a chore. Subtitles may have made them more bearable.

Among Melmo's transformations are wife and mother. I dare you to look her in the eyes and tell her she isn't gorgeous. Resources: 100 Anime, Philip Brophy, British Film Institute Publishing The Font of All Knowledge Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press TezukaOsamu website Anime News Network The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Apr 28, 2018 11:45 am; edited 2 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Toei Magical Girl Miscellany

Toei made seven more magical girl series before giving up on the genre for over a decade. Partly to move along the Beautiful Fighting Girl survey more quickly, but mostly because for four of them I've only been able to track down the first episodes, I'm going to provide short impressions of those four elusive anime. Beautiful Fighting Girl # 9: Etsuko Sarutobi, aka Sarutobi Ecchan

Left: She may be knee-high to a grasshopper but don't take Ecchan's powers for granted. Right: Her demolition of the school kendo team. Production details: Premiere: 04 October 1971 Source material: Manga Okashina Okashina Okashina Ano Ko by Shotaro Ishinomori, published in Margaret from 1964 to 1964 - the same person who gave us Cyborg 009. Directors: Masayuki Akehi, Mineo Fujita, Hiroshi Ikeda, Minoru Okazaki, Yugo Serikawa and Yoshio Takami. Script: Shotaro Ishinomori, Tatsuo Kasai, Tadao Yamazaki and Shunichi Yukimuro. Music: Seiichirou Uno Comments: Sarutobi Ecchan returns to the rumbustious physical humour of Sally the Witch, spending the first episode introducing the veiwer to Ecchan's prowess without providing any back story. In short order she sweet talks a wild dog, flummoxes her female homeroom teacher with her sudden, rapid translocations, tosses the local gang of bullies into a swimming pool, demolishes the school kendo team and the school's judo sensei, out-pitches and out-bats the boys' baseball team, and knocks out the girls' volleyball captain with a smash. The central gag is that this tiny, unprepossessing, innocent-looking girl with a mouth like Ponyo is one formidable fighting girl. She has the samurai quality of remaining motionless until acting, at which point she moves faster than the eye can follow. She also has a scream that can damage buildings. Research reveals that she is meant to be a direct descendant of Sarutobi Sasuke, the monkey jump ninja of legend, with his famous agility and speed. You can add to that psychic powers and the ability to talk to animals. Strictly speaking Ecchan isn't a magical girl, although her extraordinary abilities come across as supernatural. The atwork has a more cartoony, artificial, expressionistic appearance than Toei's earlier magical girl series, which suits the execution of its absurd premise. The action-filled first episode makes a greater impression than those predecessors, though I wonder if the underlying joke may wear thin over 26 episodes. In my review of Mahou no Akko-chan I noted how over the first three series the girls become older and the plots more serious. Ecchan takes things back to Sally the Witch, which was my favourite of the three. If it were possible, I'd watch more of this amusing anime. ANN **** Beautiful Fighting Girl # 10: Mahoutsukai Chappy, aka Chappy the Witch

Left: what happens to witches (and their kid brothers) when they upset the local motorcycle gang. Right: Chappy. The sparkly stars tell you the intended audience. Production details: Premiere: 03 April 1972 Source material: original production; a manga by Hideo Azuma was adapted from the TV series. Directors: Masayuki Akehi, Hideo Furusawa, Keiji Hisaoka, Hiroshi Ikeda, Osamu Kasai, Katsutoshi Sasaki and Yugo Serikawa. Script: Kuniaki Oshikawa, Noboru Shiroyama, Saburo Taki, Masaki Tsuji, Jiro Yoshino and Shunichi Yukimuro Music: Hiroshi Tsutsui Comments: I was able to watch both the first and last episodes - this time dubbed in Italian. Apparently it was broadcast in Japan, Italy, France, Spain, Mexico, Chile and Peru, but not in any English speaking country. We are so gauche! Perhaps programmers in the anglophone sphere weren't aware that girls also watched television. At least we did get Princess Knight. Anyway, this is standard Toei magical girl fare: Chappy is bored with the fusty ways of the magical world, steals a wand from her grandfather - the king - and a flying broomstick from a powerful witch, abducts her younger brother, and flies to the human realm where she whips up a new home with a wave of the wand. Her parents, who seem to not fit into the magical world either, follow her. Liking the setup their daughter has created they settle in with her. Also joining her is a mascot character - looking like a hybrid between a red panda and a tanuki - who drives a downsized sports car. Like Sally in Sally the Witch, she gets a saccharine friend, Shizuko, and a tomboyish friend, Michiko. Adventures follow. Unless it goes to more interesting places in the other 37 episodes then this seems to be following the instruction manual used for the first Toei series. Five years and four months after Sally the Witch the new audience may not have been born when the older series premiered. I suppose a new franchise means new marketing goodies - no hand-me-downs from older sisters, friends or relatives. ANN ***** Beautiful Fight Girl # 12: Satomi Nishiyama, aka Miracle Girl Limit-chan

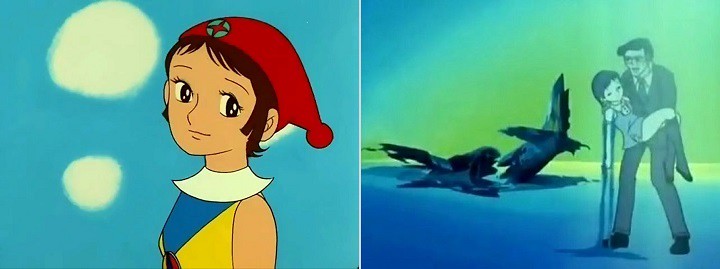

Left: Limit-chan has a sadness about her that's untypical of other Toei magical girls. Right: In a swift, savage emotional volte-face we go from schoolyard capers to mortal injury and cyberisation. Production details: Co-producers: Hiromi Productions Premiere: 01 October 1973 Source material: original story by Shinji Nagashima - an occasional resident of Tokiwa-sō - and Hiromi Productions. Director: Takeshi Tamiya Script: Masaki Tsuji and Shun'ichi Yukimuro Music: Shunsuke Kikuchi Comments: For the first fifteen minutes Miracle Girl Limit-chan gives the viewer the impression that it's going to be standard Toei magical girl fare with the usual features: an endearing protagonist with a strong sense of fairness; a gravelly-voiced tomboyish best friend; a mascot pet dog; an overweight schoolyard bully with his gang; and a pendant giving her exceptional powers. A couple of hints suggest things may not be as they appear: Limit-chan's characteristic melancholy expression and the bolted-on front legs of the dog. Then, in a tectonic tonal shift while Limit-chan is playing the piano, the viewer learns that the dog is indeed a robot, that our heroine was killed in a plane accident, and her father preserved her mind in a the body of a super-powered cyborg - something she keeps a secret from her school friends and her teachers. She asks herself, "And what am I? I'm neither a robot nor a living thing. I'm just a weird thing named Limit," then slams the piano keys. I love it when anime does those sorts of things. The mood lightens up again when Limit-chan and her friends spend a day at a theme park, but the disquieting moment has made clear the underlying existential dllemma for the heroine. Things might get worse - after all I've only seen a fansubbed first episode. According to The Anime Encyclopaedia, she only has one year to live. According to ANN, if she uses her pendant too often she will die. According to the font of all knowledge, the time limit idea was abandoned part way through the planning stage as both Hiromi and Toei thought it too grim. Only the name remained. Whatever happens, the series has a doleful underbelly that make it the more interesting than at first blush. That said, it could easily settle into a regular schoolyard routine. ANN **** Beautiful Fighting Girl # 14: Honey Kisaragi, aka Cutie Honey Premiered in Japan 13 October 1973. I'll be reviewing the Discotek release in the coming weeks. **** Beautiful Fighting Girl # 16: Meg Kanzaki, aka Majokko Megu-chan, ie Little Meg the Witch Girl

Left: Meg learns to appreciate the importance of love in a family. Right: From the OP, Meg demonstrates the cheeky side of her nature. Production details: Co-producers: Hiromi Productions Premiere: 01 April 1974 Source Material: The font of all knowledge indicates that a manga was also produced, but, as far as I can tell, it was a spin-off. Directors: Shingo Araki and Yugo Serikawa Script: Toyohiro Andô, Fumihito Imamura, Seiji Matsuoka, Masaki Tsuji, Hiroyasu Yamaura and Shun'ichi Yukimuro Music: Takeo Watanabe Comments: As a contender to become queen of the magical realm Meg is sent to earth to gain experience. She is followed by her chief rival Non and a voyeur who is supposed to be reporting back on her progress. She is adopted by the Kanzaki family, whose mother, Mami, is a former witch who married a human. Mami casts a spell to convince the family that Meg is the oldest child. The independently-minded Meg must come to terms with family life, contend with the skirt-lifting of her new brother, as well the sleazy plans of the spy and the belligerent ambitions of Non. Majokko Megu-chan has a more modern appearance than any of the Toei magical girl series that I've covered to date. Mako-chan excepted, those heroines were invariably short and often stumpy. Like Mako-chan, Megu-chan (gotta love the variety in the names) is lithe and spunky. She also gains the stringy, psychedelic, curly hair that will become di rigueur by the end of the 70s in such anime as Candy Candy and The Rose of Versailles. It's hard to pin down why but the episode has a whiff of Sailor Moon about it despite the 18 year age difference between the two shows. Perhaps it's in Meg learning the importance of familial love or in her dual with Non. Like Usagi, Meg is a bit of dill who needs to develop some competence. In any case both series are from Toei with some of the same staff. Megu is affectionate but quick-tempered, energetic but clumsy. Despite her magical abilities, her new younger brother Rabi and sister Apo run rings around her in their childish, but very physical, fights. A major development, for better or worse is up to the viewer, is Majokko Megu-chan's frequent fanservice. Meg has her skirt lifted and her blankets removed as she sleeps. She wears a sheer negligee and gets herself caught in her underwear. The odd thing is, this is a quintessential shojo anime. I think the emphasis is different from shonen fanservice, where the subject of the revelation is the male viewer. That is, the panty shot in shonen anime is part tease, part conquest, and very often accidental, a stolen glimpse by the male viewer. In a shojo magical girl anime, where the viewer is identifying with the protagonist, the moment is part violation and part excitement for the protagonist and a signal to both her and the female viewer of their latent sexuality, welcome or otherwise. However you interpret it, the fanservice is a harbinger of what's to come. ANN ****

Familiar anime tropes begin to appear through these four series. Left: Apo attacks Rabi with a weapon pulled from "hammerspace" (Majokko Megu-chan). Right: Ecchan's face assumes unnatural proportions (Sarutobi Ecchan). From this point Toei became less enamoured of magical girls. The next, Han no Ko Lun Lun (premiered 09 February 1979), isn't for almost another five years, followed by Mahou Shoujo Lalabel (premiered 15 February 1980). Because multiple episodes are available for each, I'll do individual reviews at a later time. Nature abhors a vacuum so other studios will leap in to fill the void. Source Material: Anime News Network - see indivisual links above The Font of all Knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Mar 03, 2018 8:29 pm; edited 4 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girl # 11: Jeanne, aka

Belladonna of Sadness

Jeanne: Gothic austerity meets licentious psychedelia. Synopsis: In mediaeval France a young serf couple - Jeanne and Jean - visit their lord on their wedding night to pay the marriage tax. Jean is ejected from the castle and Jeanne gang raped, led by Milord. The couple try to continue as if nothing had happened, but Jeanne is haunted by a sprite who offers her the wherewhithal to take revenge upon her tormentors. Jeanne rejects the sprite's promises yet their fortunes rise, despite some setbacks and the unremitting poverty of her fellow villagers, until an envious Milady declares Jeanne a witch and has her driven violently into the wilderness. Even Jeanne's husband rejects her, so she commits her soul to the sprite, who reveals himself to be Satan. The knowledge she gains will lead to a violent confrontation with the lord and lady of the castle. Production details: Premiere: 30 June 1973 Studio: Mushi Pro Source material: La Sorcière (aka Satanism and Witchcraft) by Jules Michelet, originally published in 1862. Director: Eiichi Yamamoto Screenplay: Eiichi Yamamoto and Yoshiyuki Fukuda Music: Masahiko Satoh Other notable contributors: Gisaburō Sugii (director of Night on the Galactic Railroad) as animation director; and Osamu Dezaki (director of Ashita no Joe; Aim for the Ace, Nobody's Boy Remi, The Rose of Versailles and Space Adventure Cobra among other titles) as a key animator. Jules Michelet and La Sorcière: Jules Michelet (1798-1873) was an historian, notable for his Histoire de la Revolution Francaise (1847) and his 19 volume Histoire de France (1833-1867). From a Huguenot protestant background, he was liberal, anti-clerical, a democrat and a pantheist. Unsurprisingly, he loathed the Middle Ages, which he viewed as empty and turgid, while the Renaissance was a dynamic rejuvenation of European culture. Although he was exhaustive in his research and generally factual, his polemical approach and his literary skill made him, according to some, untrustworthy. La Sorcière examines, in a highly imaginative fashion, the circumstances of the Middle Ages that led to the church's obsession with witches. Michelet argues that Mediaeval Christianity had replaced the worship of nature with a longing for the end of the world. Stagnation had replaced innovation. The priests and the people had been split apart. The former either lived monastically or indulged in the power plays of the fuedal lords, while the latter toiled in unvarying, abject poverty without succour from their masters either temporal or spiritual. Indeed, the feudal lords and the Church contributed to the misery of the serf. Scientific endeavour had been abandoned; the only intellectual pursuit was the copying of existing texts; and what little scientific medicine was practiced was beyond the reach of serfs. They turned to witchcraft partly through necessity - the witches possessed invaluable apothecary and midwifery skills - and party through rebellion against the brutality of the lords and the stultifying conservatism of the monks and priests. The first twelve chapters of La Sorcière brings the thesis to life by sympathetically personifying it through the travails of an unnamed woman on a journey from rape to rebellion. The anime, which follows her trajectory closely, names her Jeanne.

Clockwise from top left: Death warmed up - Milady, Milord and The Priest; Death piled up - victims of the Bubonic Plague; A very different take on the Merkel Raute; and The symbol in the context of the Witches' Sabbath - see also my image of Anthy's hands here. (Revolutionary Girl Utena owes a debt, both visually and thematically, to the film.) Comments: Mushi's last production before expiring under cumulative debts, Bellandonna of Sadness (originally released in English under the title of its inspiration, La Sorcière, but later as the translation of the Japanese title, Kanashimi no Belladonna) shows its severely restricted budget in the most obvious of ways - in its limited animation. There is some, but for the most part the film consists of panning across watercolour paintings, eye-catching though they may be. Yamamato himself described it as a "patchwork film" while historian Tsugata Nobuyuki called it "inanimate animation". This shortcoming is more than made up by the artwork that is one moment austere, another ghastly, another licentious, another sumptuous. Jeanne is portrayed as a late 1960s/early 1970s movie star goddess with an, at times, almost photo-realistic face, snake-like hair and a frequently naked body. Indeed, her body is the site of much of the narrative's themes and conflicts. It is both subject and object: subject of Jeanne's aspirations; and object of possession (Satan); ownership (Jean); abuse (Milord); envy (Milady); correction (The Priest); worship (Nature); pity and desire (the viewer). I think she is one of the most beautiful female characters in anime. I wouldn't call the film exploitative however, even with the foregrounded sex and Reading La Sorcière brought home to me the different strengths of the two media - book and film. In the book, Michelet is arguing a thesis - that witchcraft was a reaction to the dreadful times of the Middle Ages - and his story of the witch is an illustration of that thesis. The book, on the one hand, is explicit if ultimately obsessive and Michelet generally sympathetic to his heroine if paternalistic, while she remains secondary to his ultimate aim of critiquing her times. Don't get me wrong, her tale is imaginative. You could classify it as a Gothic romance in the tradition of Charles Maturin's Melmoth the Wanderer, William Godwin's Caleb Williams or The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner by James Hogg. Yes, it's masculine Gothic in its emphasis on horror rather than terror, which possibly accounts for Michelet's somewhat patronising approach to his female character. (My appreciation of 18th and 19th century Gothic fiction predates my love of anime. Perhaps it made me susceptable.) The film, on the other hand, must find oblique ways to get inside its protagonist's head. It is most effective polemically when it is suggestive or implicit. Belladonna can't lay out its arguments clearly as the book can, so it is more susceptible to both tedium and misunderstanding. Be warned.

The body emphasised, or, the living witch in a dead era. Clockwise from top left: Traumatised wife as her husband sleeps; Queen of nature in her hermit's cave; Satan's priestess (he's forming from the smoke behind her); and Object of desire. The film adds lustre to the story via its greatest strength, the artwork. The Gothic elements are presented grotesquely, the mediaeval poverty sparely. Yamamato isn't afraid of empty space on the screen. He makes a virtue out of necessity. Scenes are panned until the last pencilled line ends. Characters move from a detailed background into nothingness. Conversely, images erupt from blank space. This eruption points to the second aesthetic element of the film. To its Gothic premise Belladonna adds a delirious psychedelic antidote. It's a masterstroke and a marriage of heaven and hell that works wonderfully well. (My allusion to William Blake is deliberate - the poem makes an analogous argument.) Gothica is death in all its emptiness; psychedelia is life in all its riot. Each is excess, each is dangerous. In the end, life is unquenchable - Michelet's revered Renaissance will surely arrive. The psychedelia shouldn't surprise, being prominent in both A Thousand and One Nights and Cleopatra. Given that Tezuka's creative contribution to Belladonna was minimal, the films point to which of the two - Tezuka or Yamamoto - were responsible for what in the ealier works. My estimation is that the psychedelia is Yamamoto's - you don't see it in Tezuka anime made without him. Conversely Tezuka brought a ribald, quirky humour to anime that Yamamoto eschews. Yamamoto's eroticism is sinuous and dreamlike by comparison. Yamamamoto has a painterly style, while Tezuka adds a manga sensibility. Minimal animation limits them both. Yamamato's embrace of empty space on the screen will be followed by directors like Kunihiko Ikuhara, Akiyuki Shinbo and even Isao Takahata. Rating: The artwork is a masterpiece by anime standards, the animation weak. I'd rate the story as so-so, but the thematic exploration excellent. If you're as thick-headed as I am, you may require research and consideration to be rewarded with the gems to be unearthed. Overall I've rated it as decent.

Jeanne as revolutionary. Top row: at her auto-da-fé, the peasant women's faces are transformed into Jeanne's. Bottom left: the film concludes with images from the French Revolution, including The Women's March on Versailles. Bottom right: Liberty Leading the People was added for the 1979 Japanese re-release. It is also referenced in Cleopatra. Revolutionary France will soon inspire further groundbreaking anime. The demise of Mushi Productions concludes a chapter in this grand survey. Until this point, Marvellous Melmo excepted (and that was made by Osamu Tezuka in any case), the female protagonist had been the preserve of just two anime companies: the corporate driven Toei and the auteur inspired Mushi. From this point refugees from the failed state of Mushi, graduates from the "Toei University", and new generations of animators will use the groundwork laid by the two to enrich anime and take the Beautiful Fighting Girl to altogether new places. Resources: La Sorcière, Jules Michelet, trans L J Trotter, Simpkin, Marshall & Co ANN - I strongly recommend Gabrielle Ekens's review The Font of All Knowledge Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle Film Journal International Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Mar 03, 2018 8:13 pm; edited 2 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

yuna49

Posts: 3804 |

|

||

|

Looking at this Jeanne's visage makes me wonder if it didn't serve as an inspiration for the character designer for Shingeki no Bahamut. Jeanne d'Arc in that series has some similarlties to the Jeanne of Belladona of Sadness though not the full lips.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

There's nothing in either the book or the film that explicitly says Jeanne is Joan of Arc. For instance, Jeanne doesn't participate in any military campaigns. I don't doubt, though, that Michelet had Joan of Arc in mind as an archetype.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girl # 13: Hiromi Oka

Aim for the Ace! (Ace o Nerae!) Synopsis: When first year senior high school student Hiromi Oka enrols at Nishi High - notable as the #1 tennis school in the prefecture - she is Inspired by the glamorous, undefeated senior Reika Ryuuzaki ("Ochoufujin" or "Madam Butterfly" to her legion of admirers) to join the school's tennis training squad. The newly appointed coach - the recently retired Japanese Davis Cup player Jin Munakata (but known as the "ogre coach" by the students) - divines in her a latent ability undetectable to anyone else, least of all Hiromi herself. He promptly promotes her to the senior team, creating resentment amongst the senior players, especially the demoted girl, Kyoko Otawa. Ochoufujin, in her proud way, watches over her, but begins to realise, as Hiromi's talents blossom under Munakata's strict regime, that the younger girl must eventually challenge her as Japan's top junior female tennis player. Production Details: Premiere: 05 October 1973. Studio: Tokyo Movie Shinsha (TMS) and Madhouse, which was founded by former Mushi Pro staff, including Masao Maruyama, Osamu Dezaki, Rintaro and Yoshiaki Kawajiri. This was Madhouse's first anime production. Other notable anime start-up studios to be reborn from the Mushi ashes include Sunrise and Group TAC. Source material: the manga Esu o Nerae! by Sumika Yamamoto published in Margaret from 1972 to 1975 and 1978 to 1980. Director: Osamu Dezaki (and storyboarded under the name Makura Saki). Script: Mitsuru Majima, Tatsuo Tamura and Toshio Takeuchi. Music: Goh Misawa Character design and chief animator: Akio Sugino Comments: In my review/impression of Wandering Sun I suggested that its creation was a logical progression for Mushi Pro after the success of Ashita no Joe (review), but with the shonen boxing protagonist replaced by a shojo pop-singer. I also noted that Wandering Sun compared badly with the older series due to the absence of Osamu Dezaki's directorial flair. Well, Aim for the Ace! reunites Osamu Desaki with the sports anime genre - this time Shojo - at one of Mushi Pro's studio progeny, Madhouse, to welcome effect. Dezaki had been apprenticed in the art of limited animation at Mushi, but, on an emotional level at least, he eclipses his former master, Osamu Tezuka. Tezuka and Eichi Yamamoto had explored ways of making static animation seem dynamic. One trick was rapidly changing the image on screen by means other than normal animation, such as varying the lighting or obscuring/revealing what we see. It could be a succession of still images, or two images strobed, or one image flipped. Another trick is to use a moving camera with still images - a staple of all anime today. A third trick is to use the same animated footage in multiple ways, such as re-using it in other scenes, or looping it so that it can be extended, or iterating it so that 4 stampeding antelopes becomes 44 on screen. A fourth is to use manga shorthand to denote movement, such as speed lines. Composer Tomita Isao's rhythmic soundtracks would add urgency to the scene, thereby enhancing the illusion. As a director Dezaki adds his own signature visual tricks such as the triple repeat, where an action such as a tennis slam is re-played three times in rapid succession (sometimes with the image enlarged each time), thereby multiplying the impact (yuk! yuk!) of the action. Another famous trademark is the "Postcard Memory" where a scene ends with a still that transforms into a painted version of the former simple anime image. Mike Toole does a great analysis in Dezaki's Due.

Dezaki melodrama: Hiromi pictures coach Munakata. Those sorts of things are part of the animator's toolkit, but technical cleverness alone does not make for good anime. Dezaki knows how to pace his episodes. He also knows how to ring every ounce of melodrama from a scene. This is achieved through the pacing and build-up, the visual tricks, the dialogue and internal commentary, and the musical effects. Of the last, being the early 70s you get percussion flourishes and, my favourite, a crashing note at a dramatic climax, which is then repeated using delayed echo from what sounds awfully like a Binson Echorec (or an imitation). All these effects are in the service of the drama or, perhaps more accurately, melodrama, which, as with boxing in Ashita no Joe, is to be expected with high-school shojo tennis rivalry. It sounds cheesy, and it is, but Dezaki has flair, intelligence and an innate emotional sympathy for the stories he tells. Lest this begin to read like a hagiography let me say that the character designs are often ugly, the artwork, while improved over Wandering Sun or Marvellous Melmo, is still basic and badly dated, while the story telling sometimes takes the melodrama too far. That said, I remained fully engaged throughout: Aim for the Ace! is compelling stuff. Hiromi Oka introduces a new type of female character to this survey, but one which is now common in the 21st century. Unlike the monstrous, charismatic Joe Yabuki of Ashita no Joe, she is every girl - not especially talented at school, clumsy both physically and verbally, and straightforwardly honest. Though the anime has its gags, this is a serious story. Like Ashita no Joe it's about the development of character. Where coach Danpai Tange must direct Joe's animal instincts into something productive, coach Jin Munamata pushes Hiromi to discover within herself her latent tenacity, resilience and tennis smarts and to develop her terrific speed and potential strength. He could be infuriating at times - not just for his terrified students, but also the viewer. I wouldn't rate him as a good coach in that his severe methods would, in real life, lead to permanent injuries. Also, he wouldn't ever take Hiromi into his confidence. He wouldn't tell what she was doing wrong or how to remedy the problem. Instead he would throw her into a diabolical situation and leave it to her to figure it out. The series also promulgates that old Japanese belief that, no matter how severe the odds or bad the preparation, pluck and determination will win the day. Japan lost a World War with that attitude; British polar explorers needlessly and pointlessly wiped themselves out trying to prove the same. That said, the show allows Hiromi to make her own discoveries, to grow in the process, and to become more self-aware. She will, in time, chart her own course and, in a progressive-for-1973 moment, decide that her tennis career is more important than the boy she loves (and who loves her). She's a great character.

Clockwise from top left: Hiromi's comic best friend, Maki; This shot with Hiromi and her pet cat Goemon tickled my fancy; As with Ashita no Joe, the series is set within an industrialised community; and Madam Butterfly struts her stuff. Her best friend, Maki, is a treat. A clown who provides much of the comic relief, she gives Hiromi unstinting support. You couldn't wish for a better friend. Ochoufujin is another prototype character: the beautiful, talented, rich girl who is the idol of all the younger students. She is fully aware of the responsibility this entails - guiding them and watching over them. Beneath the glamorous exterior, though, she is ruthlessly ambitious, with the arrogance you may expect from someone with all the advantages she has been blessed with. She is hostile to Hiromi at first, probably in reaction to her friend Otawa being ejected from the senior squad to make way for the young upstart. When Otawa sabotages Hiromi and the senior team, Ochoufujin will look out for Hiromi, but when coach Munakata forces her and Hiromi to enter the prefectural doubles championship as a pair, she reacts poorly. Her growing rivalry with Hiromi will force her to re-evaluate herself. Really, none of the characters are bad at heart. Even the catty Otawa and the fearsome opponents from other schools end up as sympathetic characters. To be expected from Dezaki, and like the best anime, the plot is driven by the ambitions and fears of the characters. Sure, they're exaggerated, but they aren't contrived. Despite the popularity of the manga (over 15 million copies sold), the original broadcast rated disappointingly, resulting in the planned 52 episodes being reduced to 26. Re-runs were much more successful, leading to a re-make five years later, a film compilation, two OAVs and live-action TV drama. Although aimed at school girls it proved to be surprisingly popular with both sexes, proving that female protagonists could have universal appeal. It was also highly popular in continental Europe. (Again, why was the Anglophone world so backward?). It has been a revelation watching an anime that introduces tropes that have since become stale. Rating: as a pioneering series, a revelation; as entertainment: good. Enduring and entertaining character prototypes and tropes combine with melodramatic flair from Osamu Dezaki to create a compelling series with wide appeal. On the downside the melodrama can go too far, while the character designs and artwork can range from prosaic to ugly to dated. It deserves a subtitled release.

The Leaning Tower of Tokyo watches over us. Resources: ANN - again I'll recommend Mike Toole's article, Dezaki's Due The Font of All Knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Postcard Memories, Osamu Dezaki’s Directional Style **** The next two series in the survey - Cutie Honey and Heidi, Girl of the Alps - have, between them, 78 episodes. I expect it will take between four to six weeks to watch. I'm looking forward to them. Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 20, 2019 3:29 am; edited 2 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girl # 14: Honey Kisaragi, aka

Cutie Honey

Honey in her everyday form (left) and in her superpowered form as Honey Flash (right). Premise: Honey Kisaragi is called home from school one day by her inventor father, only to find on arrival that he's been killed by the criminal Panther Claw gang, led by Panther Zora and Sister Jill. She also finds his message revealing that she is an android possessing within her his most powerful creation - the Atmospheric Element Solidifier - a device that can transform one substance into another, such as air into diamonds (hence the interest of the Panther Claws), or android schoolgirls into, well anything you care to imagine. With her brazenly cheeky demeanour, Honey sets out to kill every last Panther Claw as payback. She's a "Fighter for Love", you know. Production Details: Premiere: 13 October 1973 (12 day after Toei's other cyborg magical girl Miracle Girl Limit-chan). Studio: Toei. Creator: Go Nagai, who also gave us Devilman, Mazinger Z and Violence Jack among other creations. A tie-in manga ran in Weekly Shōnen Champion from 01 October 1973 to 01 April 1974. Even then anime and manga were being produced simultaneously to cross promote each other. Orginal character design: Go Nagai and Ken Ishikawa. Director: Tomoharu Katsumata. Script: Keisuke Fujikawa, Susumu Takaku and Masaki Tsuji. Music: Takeo Watanabe.

Sister Jill, Panther Zora and the highly disposable henchmen. Comments: Cutie Honey has become something of an icon as a shonen beautiful fighting girl. Oddly enough, the original plan had been to create her as a shojo heroine on the NET TV time slot given to previous Toei magical girl shows. When, to make way for Miracle Girl Limit-chan, it got pushed into a later time normally set aside for shonen shows, Go Nagai quickly re-tooled it by cutting back on the romance and upping the ante on its raunchiness. In the process he created one of the formative anime in the history of the beautiful fighting girl. Viewing the show for the first time, via Discotek's 2013 release, I'm caught between admiring its innovations and dismissing it for its inanities. Go Nagai claimed that Cutie Honey was the first ever shonen manga with a female protagonist. Right off, he is telling us that anime is secondary to manga in the corporate and creative scheme of things. I'm not familiar enough with manga to affirm the claim, but this survey suggests it is true of anime at least. It also suggests that important elements of the beautiful fighting girl phenomenon have their roots in shonen franchises. The Cyborg 009 films had already provided an example, though Françoise Arnoul was firmly secondary to Joe Shimimura. Later in the survey I'll look at some of the early examples of what Tamaki Saito calls the "single splash of crimson". (More exploration!) In discussing Cutie Honey Saito also says that Go Nagai was responsible for the "original otaku-esque sexuality". Otaku culture would blossom in the wake of 1974's Space Battleship Yamato; the first Comiket will be held in 1975. The innovations don't end there. New magical girl elements are debuted, which will become staples of later anime. Until now Toei's magical girl transformation sequences had been cursory: a wave of a wand (or other magical device) or the utterance of the requisite mantra, followed by a few twinkle effects, and a new girl stands before us. Mushi's Marvellous Melmo pushed the temporal and sexual boundaries by providing a somewhat more elaborate transformation that results in an older girl much too developed for the child's clothing she is wearing. Honey takes it a few steps further. In time-honoured shonen fashion the action stops mid-battle as the villains demand to know who Honey really is. At this invitation she recites all the previouis transformations in the episode then declares loudly that her real identity is Honey Flash, at which point she leaps upwards, her outfit is shredded as she performs several mid-air pirouettes that display her naked body from every angle, before being re-clad in her superhero form. The undressing of the magical shoolgirl has arrived in anime. And not just in the transformation sequence: Honey suffers from frequent costume malfunctions - much to her embarrasment, but to the delight of her male companions. Go Nagai's manga Harenchi Gakuen (Shameless School) had not long before introduced this form of ecchi humour. He said that he was depicting Japan's culture of shame, which is itself a from of eroticism.

Three of my favourite Honey transformations, each stiched from panned shots up her body. Those hips! Also introduced to the magical girl tradition, and again adapted from shonen anime, are the now commonplace magical attack announcements, such as "Flash Beam" or "Boomerang Flash". The latter, utilising her armband, is a direct inspiration for Sailor Moon's magical tiara. Indeed, Sailor Moon owes an enormous debt to Cutie Honey. Not just Sailor Moon. Honey's breezy, even cheeky personality, her comic civilian behaviour, her upfront sexuality and her fighting prowess prefigures future protagonists in anime from the 80s and 90s, such as Daicon IV, Dirty Pair, Dominion Tank Police, or even Patlabor. The "Boomerang Flash" is a deadly weapon that severs the jugular of many a male Panther Claw mook. The casual slaughter of legions of useless men will become a trope in later girls with guns anime. (I've said before that it's a wrinkle on the magical girl genre). Noir might be viewed as the thinking person's Cutie Honey. They share the concept of a secret organisation led by powerful women; that men are simply fodder to be mown down - Honey's kill count may well exceed Yumura Kirika's; and they even have analogous tragic origin stories - the death of parents at the hands of the evil organisation. While previous magical girl shows had involved fighting, Cutie Honey is the first to have eros and thanatos overtly linked. The beautiful female protagonist is now a killer. While the show is equal parts a comedy, it doesn't mince its brutality. Episode 16 has fishermen shockingly beating a mermaid to death and the very next episode includes the unexpected immolation of a friend in a school fire. I'm not surprised that episode 18 had the highest rating in the original run - 11.8%. Over the 25 weeks it hovered around 8% to 10%. Otaku anime these days would kill, so to speak, for those sorts of numbers. A central element is the contrast between all the many frightful women who populate the series and the fetishised Honey. It's a kaleidoscopic fantasia of teenage boys' nightmares and wet dreams. The typical episode is structured around the remote Panther Zora berating Siste Jill for failing to kill Honey or retrieving the Atmospheric Element Solidifier, followed by Sister Jill recruiting a new harpy, each with her own peculiar killing powers, who then confronts and is killed by Honey. The Panther Claws are all variations on the terrifying woman, sharing claws, fangs, musclebound limbs and enormous breasts. They are not only vagina dentata embodied, they are also represent the evil mother standing in the way of the otaku's desire: Honey. In this vision the otaku is the passive subject. Honey is the active fulfilment of our dreams. Her transformations are one fetish after another: model, rock star, air hostess, biker, jungle girl, to name a few. She has a simple personality and no character development, yet she can appear in any way we, the viewers, may fantasise. Her appearance is the essential trope of the series, and a highlight at that. The "normal" women of the show - the teachers and students' mothers - are, like the Panther Claws, repulsive, suggesting the male fear of domestic entrapment. They are rendered safe by their ridiculousness.

A selection of the Panther Claws, all variations on a theme repeated over and over. If all this suggests a sophisticated, entertaining show, then I've misled you. If you're after a tits and arse fest then Cutie Honey comes highly recommended. My summary of the episode structure in the paragraph above is a surer guide to what's in store. The episodes are formulaic and dull; the characters as flat as you'll ever encounter; the thematic arguments fully explored by the end of episode 2. Too many episodes hover between tiresome and unpleasant. Thankfully they are unexpectedly short, thanks to the OP, ED and extended next episode previews taking up about 6½ minutes of the 25 minute run time. The famous OP song describes Honey's body while simultaneously inviting us to touch it and begging us not to. It's tolerable. I much prefer the more sentimental and soulful closer. Visually, the series fully embraces Toei's previous leanings towards expressionism. The backgrounds are angular and simple yet highly suggestive, while the colours are garish in their palette, their contrast and their intensity. At times Cutie Honey is downright surreal - the showdown episode with Sister Jill in her underworld is a highlight and even manages to throw in at least one surrealist homage. There's a school tower that's a barely disguised penis in all its glory, even displaying the glans at one point. Apparently the manga was more explicit in its sex and violence. Goodness. Rating: For its place in the development of the beautiful fighting girl, canonical; for its depiction of women, interesting; for its entertainment value, not very good; overall, so-so. Cutie Honey pushes the genre in a productive direction by introducing new tropes and by exploiting the viewers' desire for a more erotic content and themes. It is let down by its formulaic narrative and character frameworks.

Top: the "normal" women of the anime. The lesbian character on the left would be offensive to many. Bottom: Honey's adoptive family reacting to one her wardrobe mishaps. Reference material: ANN, particularly Mike Toole's article, A Bit 'O Honey, and Carl Kimlinger's review Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press The Font of All Knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Mar 03, 2018 8:17 pm; edited 1 time in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

I'm making my way through Isao Takahata's 52 episode TV series Heidi, Girl of the Alps, but it'll be a couple more weeks before I finish. Rather than leave this thread fallow I thought I'd look at some of Takahata's earlier films - they don't require the same time commitment from me - to get some idea where he's coming from.

The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun aka Little Norse Prince

Everything you need to know about Hols's character can be seen here: he fights; and he's dour. Synopsis: When his hermit father dies, Hols sets out with his pet bear, Koro, into the bracing Nordic world to seek out human company. He soon finds himself setting his wits against Grunwald, the demonic overlord of the north. He also earns the admiration and suspicion of the residents of a fishing village when he kills a giant pike that is eating all the fish in their river; and befriends Hilda, a mysterious, solitary girl whom calamity follows wherever she goes. Hols must convince the villagers to rally together to fight adversity; unravel how Hilda is connected to Grunwald; and vanquish the demon lord using a re-forged magical sword. Production details: Premiere: 21 July 1968 (49 years ago to the day, as I write). Director: Isao Takahata Studio: Toei Doga Source material: The Sun Above Chikisani, a puppet play by Kazuo Fukazawa, which in turn was based upon an Ainu epic. Animation director: Yasuo Otsuka Character design/key animation: Yoichi Kotabe Concept art/key animation/scene design: Hayao Miyazaki Key animation (among others): Yasuji Mori, a veteran from Nichido Eigasha and mentor to Isao Takahato, who descibed his influence on anime as "incalculable". Music: Michio Mamiya Backround: With Toei Doga struggling to make a profit in the early to mid sixties, salaried animators were forced to work long hours for poor remuneration. (Sounds very much like the present day. Perhaps it was ever thus.) In 1961 staff unionised and presented a set of demands to the studio. Some months later union members went public with their grievances. The studio responded with a lockout (or, for some, a "lock-in" - animators had been working overnight when the gates were closed at 9 am). After four days the parties reached a compromise. Disputes continued through the sixties. Horus, Prince of the Sun went into production shortly after yet another labour dispute. It is worth noting that both Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki were union activists at Toei Doga. The film, which might be considered an allegory of the activist (Hols = the union organiser = Takahata/Miyazaki), leading the collective (the village = the unionised animators) to resist their oppressors (Grunwald = Toei), flopped at the box office. In Anime Explosion Patrick Drazen suggests that Toei deliberately gave the film a limited cinema release because "the bosses at Toei either didn't know quality when they saw it, or felt the need to stick it to the union types like Takahata and Miyazaki." Both left Toei shortly afterwards. Jonathon Clements, quoting Taku Sugiyama, says that the quality of Toei's output had two significant plateaux: first in 1962 when the effects of the industrialisation of the animator training process had diluted the talent base of the company; and the second in 1966 when the company replaced salaried staff with contractors in response to the labour troubles.

Clockwise from top left: Koro the talking bear cub provides the usual Toei comic relief by cute animal; Think of Drago as a sort of anime version of Wormtongue from Lord of the Rings, but comical; Horus confronts the giant pike; and Grunwald enjoys his moment of mayhem. Comments: One of the interesting things about Horus, Prince of the Sun is how it contains within itself key elements of the early Toei films, while simultaneously presaging elements that will become characteristic of Studio Ghibli, founded by Takahata and Miyazaki some time later. The most obvious way this can be seen is in the character designs. Although they thankfully avoid the salaciously oversized mouths of Magic Boy, they include other designs that are typical of Toei productions of the time. Check out Drago and Grunwald in the images accompanying the review. Even Hols is a variation on Joe Shimamura from Cyborg 009. Ghibli-esque character designs can be found among the faces of the villagers. It's as if they were using the support characters as test dummies for the future. Another contrast is in how the film retains the obligatory cute Toei talking animals who, again thankfully, don't sing, while maintaining an otherwise serious tone (though not as dark as Toei's Anju to Zushio Maru from 1961, which includes the suicide of a major character). There's a bear cub, a squirrel and an owl. Actually, the owl turns out to be quite a sinister fellow, so points to Takahata et al. The singing is left to Hilda, who also plays a lyre, and to the villagers. Her songs are melancholy laments with sometimes bloodcurdling lyrics, while theirs celebrate the bounty of the river or the joys of marriage. Either way they lack the kitsch inanities Toei inflicted upon us previously. The comic content of the film is, like Anju to Zushio Maru, very much secondary to the otherwise more mature sensibility on display - one that will become a feature of Ghibli. The quality and style of the animation is another case in point. While Toei films might be scheduled for as little as eight months for production, Takahata, Miyazaki and Otsuka determined to take as long as needed to make the film to the standard they wanted. It took them three years. The time spent shows. Two of the action scenes are in a league of their own. The opening sequence has Hols desperately fighting against a pack of wolves. The action is kinetic, alarming and violent. It ends abruptly with the appearance of a rock golem, but that's Hols, Prince of the Sun for you - it rarely stops for breath. Each scene proceeds economically and relentlessly to the next. The later pike scene is choreographed like nothing before from Toei, with a new-found immediacy and impact. It's not all good, however. There's a wolf attack and, later, a rat attack on the village that consist entirely of stills. Perhaps three years production time wasn't enough? Too often in non-action scenes the characters revert to that Toei feature film habit of moving too slowly, as if the air had become viscous. After three or four viewings the climactic showdown between Hols and Grunwald in his icy lair seems perfunctory, especially after the spectacle of the the ice mastodon attacking the village in the preceding scene.

Hols and wolves (top); Arren from Tales from Earthsea (bottom). I've always considered the newer scene to be a homage to the older. With one notable exception the characters are disappointing. Hols might just be the most boring protagonist in the Takahata/Miyazaki body of work. He fights, he kills, he moves forward. I couldn't tell you if he was good or bad because we never get inside his head. Like Ashitaka in Princess Mononoke his personality and his motivation are entirely subjugated to the thematic needs of the narrative. His ideas are fundamental, and like all fundamentalists he is totally devoid of wit. Hence the cute animals, I guess. I also get that a major theme is rebirth and renewal, hence the youth must overcome the adult villain. That may work elsewhere, but here he seems too much like just another shonen hero self-actualising through fighting. The film would have been far more interesting if he were female. But I would say that, wouldn't I? In its gravity, its violence, its themes, and its technical accomplishments the film is groundbreaking as far as animation goes, but the story of the boy who goes into the world, fights against the odds and succeeds has been told a million times in many forms, including cartoons. Sally the Witch may be more juvenile and Princess Knight more eccentric, but both, particularly Princess Knight, by introducing a subversive female fighting protagonist, are revolutionary in a way Hols, Prince of the Sun simply isn't. Grunwald is just another evil villain who wants to rule the world or, if he can't get his way, destroy everyone. And, yes, he laughs the evil villain laugh. He has the seemingly redeeming trait of overreacting to setbacks. That combined with Mikijiro Hira's restrained voice and almost self-effacing delivery give him a sort of panicky air. I think it unintentionally makes him more sympathetic than intended. You've also gotta have some sympathy for a guy whose only confederates are crows and wolves. As Ursula Le Guin said of the Ghibli take on Tales from Earthsea, "evil has been comfortably externalized in a villain, ...who can simply be killed, thus solving all problems." As the evil laugh indicates, Grunwald's thematic role is completely devoid of nuance. He is no Lady Eboshi (Princess Mononoke) or even Kushana (Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind), who have genuinely redeeming qualities.

Hilda with her good angel, Chiro. The most interesting character is Hilda. Unlike Hols or Grunwald she is conflicted. Also unlike them she is hard to read at first. Hols will fight until he wins; Grunwald will fight until he loses. As simple as that. Hilda is altogether more complex. Hols first hearing her singing, then searching for her in the derelict seaside town is a magical sequence. With her simply drawn but expressive face, her singing, and her tragic air she is quickly sympathetic, despite her reticence and her vague warnings that she is the harbinger of disaster. As the film proceeds we get new, clearer but still incomplete glimpses of what she truly is. She is accompanied by a squirrel and an owl who act as her good angel and her bad angel respectively, urging her this way and that. When her villainous side prevails and she attacks the village with a plague of rats, she is disturbing in a way that Grunwald cannot manage. She has a genuine loyalty to Grunwald, but a yearning to be part of humanity, complicated by a growing regard for Hols. Although she will slide into familiar tropes by being redeemed by the male protagonist, she remains the only characters with complicated motivations. Not being as obviously allegorical as Hols or Grunwald, she has more narrative space. Her motives drive her contribution to the narrative; their thematic requirements drive theirs. She is the forerunner of later Ghibli characters with both negative and positive traits. Rating: good. Hols, Prince of the Sun introduces a somewhat darker, more serious tone to anime (and, as some argue, to animation generally) than viewers will have been accustomed to previously, while some of the action scenes are dazzling for their time. Despite its allegorical suggestiveness, the plot is straightforward, and the protagonist and adversary constrained by their roles., The conflicted, layered Hilda compensates for those shortcomings. The film provides hints of the greater body of work to come from Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki. Reference material: The Font of All Knowledge Anime Explosion: The What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation, Patrick Drazen, Stone Bridge Press. Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle ANN Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Mar 03, 2018 8:19 pm; edited 5 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Jose Cruz

Posts: 1796 Location: South America |

|

||

|

Interesting review of Hols, it has been about 5 years since I first watched it. I though it was a good film at the time but certainly crude compared to what Miyazaki and Takahata made later.

Many people regard it as a super revolutionary movie, like, the movie that redefined what was possible in animation. But I guess that as one goes deeper into the history of anime like you are doing one notices that certain things weren't as revolutionary as previously thought. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Here's an interesting thing. My ordered copy of Hiroki Azuma's Otaku: Japan's Database Animals arrived this morning, about five hours after I'd posted the review. Had I received it earlier I would have dealt with the following quote from the book:

Rather than revolutionary, Azuma describes the film as orthodox and conformist. The quote is his only mention of either Takahata or Miyazaki in the entire book. One of my theses that I'm exploring in the grand survey is that the evolution of the beautiful fighting girl is inextricably tied in with appearance of the otaku in Japanese culture. While there is a split between Studio Ghibli and otaku aesthetics, I am still convinced that many of the best beautiful fighting girls of the 90s and 00s owe much to Miyazaki's Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind.. |

|||

|

|||

|

Jose Cruz

Posts: 1796 Location: South America |

|

||

|

I wouldn't think as Horus being conformist to Hollywood's animation just because it has full animation (I read somewhere it has 160,000 animation cells, more than twice as many as Miyazaki's 1980s movies, by the way). While I watched a Japanese documentary on the making of Princess Mononoke which stated that Horus was "the first animation ever for young adults." In my impression it is light years ahead in terms of complexity compared to any other animation I know made before 1968 but I don't know much stuff from that time but it appeared rather special in many ways, it's very dark tone and Hilda is a rather sophisticated character (never seem anything like her in a Western Animated film).

I tend to view Miyazaki and Takahata's films as being pure animation while limited TV animation like Yamato, Galaxy Express 999 and Gundam is more heavily inspired by manga aesthetics. Yamato started as a series but was simultaneously adapted into a manga. In that sense Miyazaki's stuff is less mainstream and more "otaku" since in Japan manga has been traditionally dominant vis animation and movies in general in general popularity: manga like One Piece and Dragon Ball are way more popular than anything Miyazaki made: the magazine where Dragon Ball was serialized had 300 million copies in print over a year in the mid 90's compared to about 25 million tickets sold for Miyazaki's biggest box office success, Spirited Away. That same magazine serialized things some people here have labelled "otaku" stuff. About "otaku". I don't think that term has a well defined meaning, it's use by the population just means a person with a strong (to the point of being unhealthy) interest in some hobby. Miyazaki talks about otaku as if it were the same as a maniac obsession with something. While Tamaki Saito uses the term to mean a certain form of sexuality: it means heterosexual males who sexually attracted to heavily stilized characters designs. However, mainstream manga like the stuff in Shounen Jump has heavily sexualized and stilized characters and that has been going since the late 1960s, and Saito himself also notes that most porn manga by the 90s became highly stylized and porn manga sells about 100 million copies a year, so many millions of ordinary Japanese teenagers and porn manga readers are otaku by Saito's definition. And also, it's noted that pretty much nobody in Japan identifies as an otaku. It's a label put on others usually with bad intentions. So, in my opinion, otaku is becoming just a meaningless word and is normally/often used to insult people in Brazil as it's basically used to refer to anti-social male geeks who have trouble getting girls. And I think it should be dropped: it's like "moe cr*p" when used by Western anime fans to trash something. I think people should not use these words (even if I am guilty of using them I think I should never write them again). |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

I first watched these two short Isao Takahata films six years ago, almost to the day. When planning the great survey I deliberately excluded them as I thought they were too removed from the notion of the conflicted - or, perhaps more accurately, confronted - female protagonist. Given that Heidi, Girl of the Alps will be included, it now seem anomalous to exclude Mimiko, the heroine of...

Panda! Go, Panda! and Panda! Go, Panda!: Rainy Day Circus

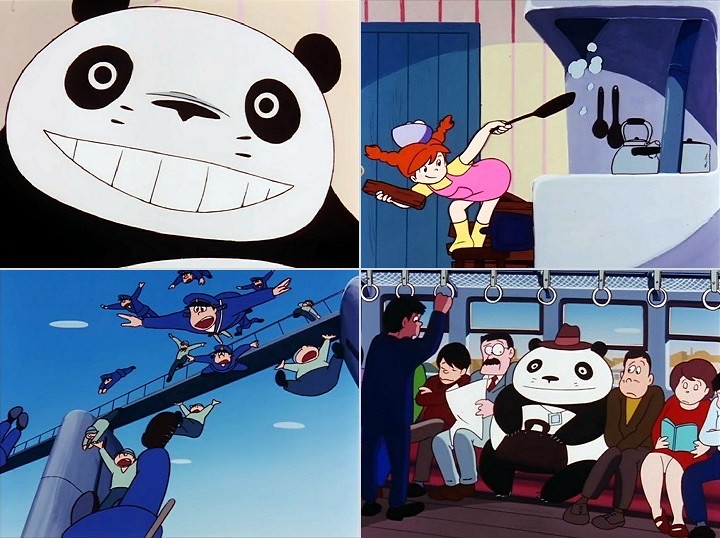

The family that plays together: Mimiko, Papa Panda and Baby Panda. (Panda! Go, Panda!: Rainy Day Circus). Synopsis (Panda! Go, Panda!): When Mimiko's grandmother leaves her to attend a memorial for her former husband, two pandas, Papa Panda and Baby Panda, move into the bamboo grove surrounding her cottage. Mimiko, who longs for a father figure in her life, invites them to move in with her. This suits the pandas - Baby Panda is in need of a mother figure and, besides, the two have not long escaped from the local zoo. Things won't stay cozy for long: pandas aren't built to live in houses; Mimiko has school to attend; and the zookeepers are going to cotton on to things sooner or later. Synopsis (Panda! Go, Panda!: Rainy Day Circus): When a circus comes to town an escaped tiger cub finds its way to Mimiko's cottage in the bamboo grove. It quickly becomes fast friends with Mimiko and the pandas. Later, a storm leaves almost the entire district under water. In her efforts to rescue the circus animals trapped in their cages on a stalled train, Mimiko sets the train off on a madcap ride through the flooded countryside. Production details: Premier 17 December 1972 & 17 March 1973 (Rainy Day Circus) Director: Isao Takahata Studio: Tokyo Movie, later known as TMS. Source material: original concept by Hayao Miyazaki Screenplay: Hayao Miyazaki Art Design: Hayao Miyazaki Animation Director: Yasuo Otsuka and Yôichi Kotabe Character Design: Yasuo Otsuka Music: Masahiko Satoh Comments: Between 1958 and 1982 the People's Republic of China gave 23 pandas to nine different countries as part of what is now called panda diplomacy. (Since 1984 China has loaned, instead of gifted, Pandas.) The arrival of four year old female Lan Lan and two year old male Kang Kang to Tokyo's Ueno Zoo on 28 October 1972 created a sensation. Queues stretched a mile from the zoo and the overall attendance numbers in 1973 reached 9.19 million, more than 50% above the previous year. The release of these two films at the height of the pandamania ensured their success. It didn't hurt either that the films are load of fun, far removed from the mostly serious atmosphere of Hols, Prince of the Sun.

Scenes from Panda, Go Panda! Clockwise from top left: Papa Panda was a prototype for the later Totoro; Mimiko is a deft hand in the kitchen; Someone needs to word up Papa Panda on manspreading and good public transport etiquette; and Police and workers dive into a reservoir for the sheer fun of it. Comical fun and constant activity are the guiding principles of Panda, Go Panda! The energy is provided by Mimiko, perhaps one of the first genki girls in anime. Her characteristic pose is a handstand with her pigtails defying gravity, unlike her slip, which ends up around her armpits. She's no idiot though, demonstrating her capabilities in her homemaking, her handling of the various animals that cross her path, and her clearheadedness in a crisis. Check out the image above - she's simultaneously flipping an egg with her left hand, opening the oven door with her right foot, inserting a log with right hand, all while balancing a bowl of eggs on her head. Papa Panda is her foil. He's slow to act, mostly pre-occupied by the beckoning bamboo grove, and always providing parental male strength when needed. He's a bit of a dill, with a characteristic bamboozled (yuk! yuk!) expression. He isn't fazed for long, though. Whether it be chairs or tables collapsing under his weight, vicious guard dogs, incompetent home intruders, or out of control trains, crises rarely upset his equanamity. That contrast between Mimiko and Papa Panda is emblematic of the films' comedy: the incongruous juxtaposition of opposites. To start off there's the innocent ménage à trois between the girl and the two pandas. The letters Mimiko writes to her grandmother must have the latter's hair standing on end. You have a huge bamboo-eating panda who relaxes by fishing; there's a scrambled version of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, where Goldilocks is one of the bears and the interloper is a tiger cub; and Papa Panda commutes to work on a peak-hour train. At times the absurd humour enters surreal territory - most starkly in the flood scenes. Combine this with Mimiko's and Baby Panda's enthusiasm along with Papa Panda's good-humoured dependability and what you get are two films brimming with happiness. Sure, there's the odd moment of drama, but the viewer can always be confident that all will turn out well.

Scenes from Rainy Day Circus. Again, clockwise from top left: Mimiko, Baby Panda and Tiny Tiger in characteristic poses; Underwater image of the trip through the flood - they're using Papa Panda's bed as a boat; Emerging from the floodwaters; and Mimiko stares down a tiger. Even more than Hols, Prince of the Sun, the Panda, Go Panda! films are a touchstone for much of the Takahata and Miyazaki body of work to come. The unwavering optimism will be repeated in Heidi, Girl of the Alps then culminate in Takahata's masterpiece, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. In her energy Mimiko prefigures Heidi, or Mei from My Neighbour Totoro; in her tomboyishness and independence of mind there are hints of Kaguya, Nausicaa, and Fio from Porco Rosso. The sense of wonder and the uncanny ability of the two directors to present the world through the eyes and mental processes of a child can be found throughout the Ghibli canon. Most telling, though, are Papa Panda and the flood sequence. Totoro is clearly a re-working of Papa Panda, although superior in just about every way. He manages to combine gravitas and enchantment in a way that the older character can't quite achieve. The flood in Ponyo may be technically superior and it may have a larger significance in it's films thematic concerns, but the brazen appropriation cheapens it. In short, Panda's is more fun. That fun aside, the films don't have a lot else to offer. Everything about them is simple, including the character designs, the backgrounds and the story telling. The animation, being Takahata/Miyazaki, is above average for its time without drawing much attention to itself. Yes, there are moments of visual magic - they are from Takahata and Miyazaki, after all. Compared with much of their contemporaries they are attractive (which isn't saying a lot). The jaunty soundtrack is adequate to the task. In the end, what you get are two amusing half hour diversions. Revisiting them has been, well, fun. Ratings: Panda, go Panda! - decent; Panda, Go Panda!: Rainy Day Circus - good. Reference material: ANN: Panda! Go, Panda!; Panda! Go, Panda!: Rainy Day Circus The font of all knowledge Zoo and Aquarium History: Ancient Animal Collections To Zoological Gardens, ed Vernon N. Kisling, CRC Press. Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Mar 03, 2018 8:22 pm; edited 1 time in total |

|||

|

|||

|

All times are GMT - 5 Hours |

||

|

|

Powered by phpBB © 2001, 2005 phpBB Group