Forum - View topicErrinundra's Beautiful Fighting Girl #133: Taiman Blues: Ladies' Chapter - Mayumi

|

Goto page Previous Next |

| Author | Message | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girls index

**** Splash of Crimson #16: Remy Shimada

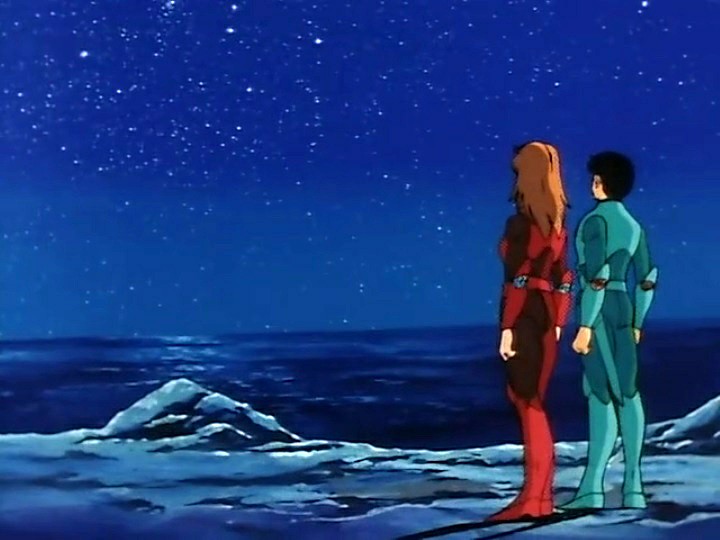

GoShogun (aka Sengoku Majin Goshogun) Synopsis: In 2001 - twenty years in the future - the world is ruled covertly by Docooga, a gigantic corporate / military / industrial complex. Their attempt to kidnap a Japanese scientist, Doctor Sanada, who has unlocked the secrets of an infinte energy source known as Beamler, is foiled when the scientist becomes a suicide bomber. His associate, Sabarath, takes the scientist's young son, Kenta Sanada, under his wing, recruits three ace fighter pilots - Remy Shimada, Shingo Hojoh and Killy Gagler - and reveals the existence of a teleporting flying carrier known as Good Thunder and a giant robot known as GoShogun, both built by Doctor Sanada and powered by Beamler energy. Thus begins a cat and mouse game around the planet as the crew use the teleporting powers to avoid Docooga and foment rebellion wherever they land. When it is revealed that destroying GoShogun will result in a detonation that will vaporise the entire solar system, the villains realise they must be more circumspect in their approach. All the while Kenta's strange affinity with machinery grows until it may just be that he can ascend to a higher level of existence. Production details: Premiere: 03 July 1981 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #29, Yayoi Yukino and Beautiful Fighting Girl #30, The Unnamed Girl with a Glass of Water) Director: Kunihiko Yuyama (Fairy Princess Minky Momo, GoShogun: The Time Étranger, Leda - The Fantastic Adventure of Yohko, Ushio and Tora, Weather Report Girl, Wedding Peach and couple of Slayers movies before becoming the creative force behind the Pokemon franchise.) Studio: Ashi Pro Source material: original production Screenplay: Kunihiko Yuyama, Shôzô Yamazaki, Sukehiro Tomita, Takeshi Shudō and Yuuji Watanabe Music: Tachio Akano Character Design: Hajime Kamegaki, Hideyuki Motohashi, and Satoshi Hirayama Art Director: Geki Katsumata Mechanical design: Gen Sato and Hajime Kamegaki

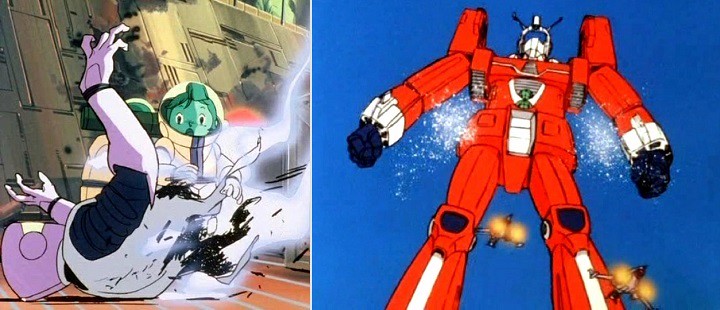

Top: GoShogun and the much smaller, almost useless Tri-3 (Captain America, anyone?). Middle: Sabarath (= Savalas, get it?) and his pilots Killy Gagler, Shingo Hogoh and Remy Shimada. Bottom: teacher and mother figure OVA and her charge Kenta Sanada. Comments: One of the pleasures of doing this project in premiere date order (the Splash of Crimson side trip notwithstanding) is seeing the shows within their original context. That's relevant here as GoShogun is an affectionate parody of titles I've recently reviewed. Had I watched it as a follow up to my original viewing of GoShogun: The Time Étranger seven years ago, and without the benefit of what I now know, I wouldn't have picked up its many references. Parody parasites its hosts and it cannot exist without them, but I must say that I enjoyed this series rather more than its multiple targets. These include Gundam for the mechanical designs; Ideon for the "kill 'em all" giant robot; both the Tomino franchises for the fugitive spaceship plot; Cyborg 009 for the characters Remy (=Françoise), Shingo (=Joe) and Killy (=Jet); the Go Nagai giant robot shows for the, you guessed it, giant robots, but also for the Destroid robot beast of the week and the shadowy, powerful big bad Neoneros with his peculiar and ambitious but mostly incompetent commanders - Leonardo Medici Bundle, Suegni Cuttnal and Yatta-la Kernagul; the train computer in Galaxy Express 999 for a pair of super computers that run the Good Thunder and the Docooga corporation, named "Father" and "Mother" respectively; and maybe, at a stretch, the character, though not the design, of Olga from Space Firebird 2772 for the child-rearing OVA. I'm sure there's other links to be unearthed with greater knowledge of then contemporary anime, especially with the eleven year old protagonist, Kenta. Yuyama's and Ashi Pro's penchant for parody will inform Fairy Princess Minky Momo, giving it an appeal beyond its target demographic, but, oddly, be largely absent from GoShogun's movie sequel, The Time Étranger. More on that, though, when I return to the main sequence. The genre aware humour pokes fun at giant robot conventions. I'll give some examples. Remi, Shingo and Killy each pilot a rocket powered fighter plane that combine to form a giant mecha they call call Tri-3 with Remy as the chief pilot. The mecha is inevitably overwhelmed by the firepower of the Docooga flying armadas - so much so that its deployment is largely pointless. Which is the point. Alternatively, the Good Thunder may launch the much larger GoShogun. This requires the pilots to manouvre their planes into compartments within the mecha in an elaborate aerial dance that takes so long that Killy reminds the Docooga, "Don't attack until this part is finished". They sportingly oblige, despite the likely consequences. Shingo flies his plane into GoShogun's chest cavity from where he controls the mecha. Remy and Killy embed themselves in its thighs from where they can do nothing of any use other than give Shingo gratuitous advice. Their main role in the circumstances is to triple the agony when things go awry. The best battle is when Docooga builds an identical giant robot, other than its more evil looking colour scheme. When the two grapple they are so evenly matched that they remain motionless while observers wait impatiently for something to happen. GoShogun will, naturally enough, pull a rabbit from a hat, in the form of the GoFlasher - a five-pronged array of light beams that transform in the most surprising way any machine caught in their radiance.

Docooga vilains. Top left: Suegni Cuttnal may look and act like a pirate but he also runs the world's largest pharmaceutical company. Middle: big bad Neoneros in one of his transformations. Right: Yatta-la Kernagul's punching bag personal assistant turns against its master after being hit by the GoFlasher Bottom: When this Docooga mecha deploys to Chopin's Revolutionary Etude, Leonardo Medici Bundle (right) observes, "Such power; it gives me chills." GoShogun is also a fun character-based comedy. Although Kenta is nominally the protagonist, as the only non-adult character he is outshone by the wise-cracking pilots, his anxious robot nanny OVA, byTelly Sevalas clone Captain Sabarath and, eventually by the three Docooga commanders. His role is central to the outcome, but his juvenile personality is something of a drag on proceedings, or, as Killy puts it, "A child protagonist is so hard to accept." Hey, even the anime itself understands its own limitations! As the series progressed I warmed to the three pilots with their banter, the double-entrendres, the bravado and the sharp digs. Blond Killy is something of a poseur, seeing himself as a lady's man. His ambition is to write a best-selling autobiography. Happily his self-effacing ironic demeanour should erase any doubts the viewer may harbour towards him. Shingo, chief pilot of GoShogun, is the action man of the team and the one who is most often seen in the gym or practising at the shooting range. He is the straight man - though no idiot - to Shingo and Remy. (More on her shortly.) In an episode with a George Harrison lookalike character, Shingo is depicted as Paul McCartney. That's GoShogun for you: lots of unmarked visual and audio gags. Pick of the villains is the effeminate, cultured Leonardo Medici Bundle. His camp posturing is something of a cliche these days, but he is the earliest example of the type I know of in anime. Most of the battles he commands are accompanied by a soundtrack of famous classical pieces, sometimes reflecting what's on screen, other times in ironic contrast. Edvard Grieg's "Morning Mood" from Peer Gynt is a good example of the latter. When "The Blue Danube Waltz" plays to an otherwise lame shout-out to 2001: A Space Odyssey, Shingo identifies it as composed by Johann Strauss. No, it's not fourth wall breaking (although that occurs from time to time). It turns out that Bundle is actually broadcasting the music from his attacking aircraft and mecha, a la Colonel Kilgore blasting "The Ride of the Valkyries" from his attack choppers in Apocalypse Now, released only two years earlier. Bundle likewise uses Wagner (Lohengrin), and also Chopin ("Revolutionary Etude"), Rossini ("William Tell Overture") and a piano piece by Lizst I'm not familiar with. The regular soundtrack is a sort of synth-pop. In a nice touch, during an episode set in Munich, the style abruptly changes to classic Krautrock sequencer rhythms. Getting back to Bundle, he constantly trolls his co-commanders, Cuttnal and Kernagul. It's a wonder they don't beat the crap out of him. The blue-skinned, musclebound Kernagul keeps a stress relief robot handy that he beats up instead. He's actually more interested in his worldwide chain of hamburger franchises than fighting. Cuttnal is addicted to tranqilisers - happily for him he controls the world's pharmaceutical industry. The least amusing of the villains is their shadowy prime mover Neoneros, who watches on patiently while his minions snipe at each other. He doesn't need to be much more than that, but proves he is in an absurd escalation of his powers in the final episode.

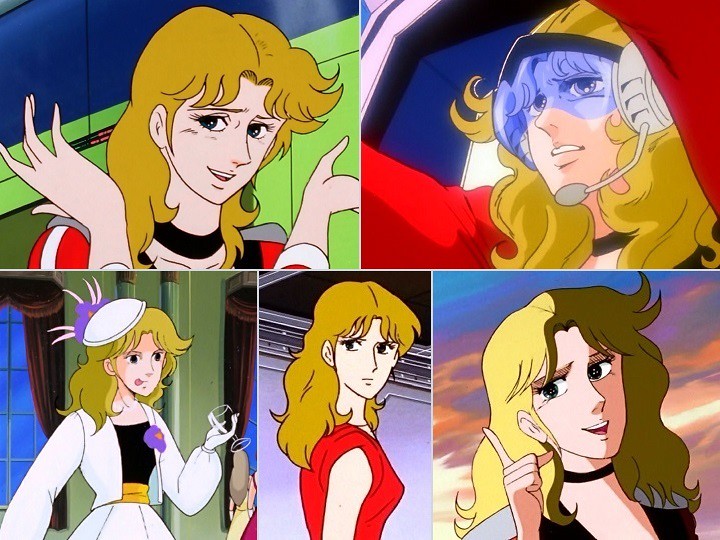

Five faces of Remy Shimada (clockwise from top left): sceptic, warrior, contrarian, doubter and drunkard. Remy Shimada: Given equal billing to the other two pilots - both Shingo and Killy concede she is the most capable among them - Remy is the culmination of the development of the otaku-targetted mecha / sci-fi heroine to that time. She is both older and more credible than any of the Go Nagai and Yoshiyuki Tomino female pilots encountered in this survery; more fun than the Tomino female characters who are similarly aged; much more layered than Space Battleship Yamato's Yuki Mori or Cyborg 009's Françoise Arnoul and altogether superior to the absurd Cutie Honey. Only Maetel from Galaxy Express 999 shades Remy, but the narrative and thematic roles of the two are profoundly different. Part of the skill of the GoShogun's creative team is their ability to switch seamlessly between comedy and sci-fi action. Remy is no exception. She is a comedienne without becoming a clown; gives as good as she gets in the banter with her fellow pilots; and, while no genius, isn't anyone's fool either. Part of the strength of her depiction is how her sex has no bearing on how her abilities are perceived by the other characters, even if they wouldn't mind romancing her. Shingo and Killy happily accept her as their comrade and equal. That said, GoShogun is aimed at a male audience, so she is the butt of sexual jokes and gendered humour. One of her constant gripes is that she is committed full time to battling Docooga while her marriageable years slip by. Given that in the sequel film, which is set 40 years later, she is 70 years old, then she is between 27 and 30 over the TV series. Kudos to Kunihiko Yuyama for having a heroine of that age, but the "left on the shelf" jokes do get repetitive. And I might also add she is the only recurring female character, if the motherly OVA is excluded. Courageous news reporter Isabelle Cronkite - the daughter of a famous newscaster - is another female of substance in the series, but only appears in three or four episodes. Rating: For its entertainment value, very good; if you're not familiar with the franchises it parodies, then some of its impact will be lost, reducing the rating to good. There's still plenty to enjoy otherwise: a clever script, absurdly funny scenes, entertaining banter between a bunch of appealing characters and likeable villains. I enjoyed it somewhat more than any of the other mecha series reviewed in this survey. Perhaps GoShogun is the mecha series for people who aren't into mecha. Note also, the TV series is markedly less serious in tone than the sequel movie (if you haven't figured that out already). Resources: GoShogun: The Complete TV Series, Discotek ANN The font of all knowledge

Last edited by Errinundra on Mon Feb 14, 2022 3:35 am; edited 4 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

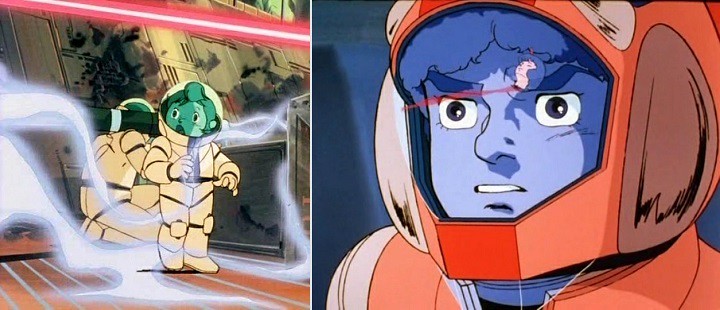

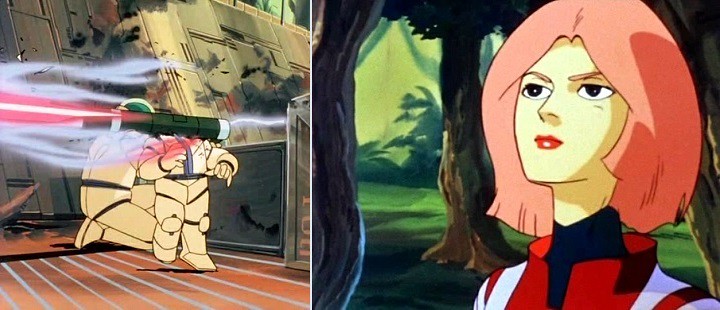

Splash of Crimson #17, Karala Ajiba and Sheryl Formosa

The Ideon: A Contact The Ideon: Be Invoked Synopsis: See the equivalent paragraph from Space Runaway Ideon above. The first film - The Ideon: A Contact covers up to episode 32 of the series, although some events are juggled. It begins with the discovery of the Ideon, contains highlights of the battles between the human Logo Dau runaways and the alien Buff Clan, then concludes with the death of one of the Ideon's pilots - Moera - and Sheryl Formosa's return to the Solo Ship from the super computer at the Earth's moonbase with important data about the giant robot and its infinite power source. The Ideon: Be Invoked continues to the point in the series where Doba Ajiba repudiates his daughter Karala, who is pregnant with her and Bes's child. (The Solo Ship crew have named the child Messiah.) From there the tale tracks a different path from the TV series. The Solo Ship rescues Karala from the Buff Clan then escapes. Gathering the entire Buff Clan military resources, Doba surronds the Logo Dau runways then forces them into the path of his ultimate weapon, the Gando Rowa, a space station that can channel all the power of a supernova into a single beam. Surviving one blast from the beam, Bes and Cosmo decide to attack Doba directly as Buff Clan marines infiltrate the Solo Ship and begin the slaughter of its crew and inhabitants. The Ideon attacks the Gando Rowa just as it fires. All surviving Logo Dau refugees are killed, causing the Ide to be invoked. The resulting explosion destroys the universe. The spirits of every character from the franchise are awakened, including Messiah who will guide them along a new, more loving, path. Production details: Premiere: 10 July 1982 - both films in a double bill (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #32, Minky Momo, and Beautiful Fighting Girl #33, Ranze Etou) Director: Yoshiyuki Tomino Studio: Sunrise Original creator: Yoshiyuki Tomino and Sunrise (under their pseudonym Hajime Yatate) Scirpt: Kenichi Matsuzaki, Sukehiro Tomita, Yuuji Watanabe and Hiroyasu Yamaura Music: Koichi Sugiyama Character design: Tomonori Kogawa Art director: Mitsuki Nakamura (A Contact) and Tomonori Kogawa (Be Invoked) Mechanical design: Yuichi Higuchi

Left: Two seconds of Ashura Novak's life will lead to her immortality; right: the Ideon. The nature of the Ideon: Throughout the TV series and the two films characters speculate on the powers and intentions of the giant robot. Because the characters are clouded by ignorance the viewer cannot be sure of the truth. The first film ends with a discussion among the crew of the Solo Ship about the mystery. I repeat it here (with some edits to make it shorter) as it neatly sums up the dilemmas they face and themes of the franchise. Please bear with the long exerpt and also keep in mind the parallels with the Cold War, with its threat of imminent destruction despite the supposed defensive intentions behind building nuclear weapons. - Sheryl Formosa: I'm not sure if this is the same "Ide" from the Buff Clan's legend, but we now have proof that this unknown energy from this ship and the Ideon is infinte. - Cosmo Yuki: Have you managed to figure out the control system? - Sheryl: Of course not! - Cosmo: Well, then what's going to happen? If people who have infinite power aren't able to control it, then... - Sheryl: If the infinite power is released then, theoretically, the entire universe could be destroyed. If we make a mistake then everything will be destroyed! - Bes Jordan: And if it's liberated by an altruistic power? - Sheryl: Then the Ide might be a power that's here to save us. But, that's probably the optimistic view of things. - Bes: I see. So, the Ide is the will of the Sixth Civilisation? - Joliver Ira: Yes. This ship's (defensive) barrier is sealing it in, within this space. The Solo Ship and Ideon are machines that convert it to energy. - Hatari Naburu: So, what activated it in the first place? - Joliver: Supposedly, the defence instinct of the sealed Ide. It means that Ide activated itself in response to pure self-defence instincts. For instance, since the infant Piper Lou wanted to protect himself, the Ide responded instinctively. Coincidently, we let babies like Lou aboard the Solo Ship. Thanks to that, Ide's power protected us. So that's how it is. - Cosmo: That's strange! Why would too much preservation instinct destroy us?

Right: Cosmo watches as the girl he loves - Kitty Kitten - is blown asunder. Note the reflection in his visor. - Bes: No. If Ide itself is an independent entity, it's possible. When the Solo Ship and the Ideon were completed, and the power of numerous consciousnesses become one power... - Karala Ajiba: Ide will destroy others to prevent them from invading its own existence. That may have been the fate of the Sixth Civilisation, who gave birth to the Ide. - Sheryl: It's true. We're being taken in by the Ide. - Karala: But was not the Ide under control, because of Piper Lou's consciousness? - Gije Zaral (until now not generally known to be aboard): I believe so! I believe the battle between the two different alien species hasn't ended in complete destruction yet, because of the existence of babies like Lou. - Kasha Imhof: Cosmo, how'd it get like this? How can an enemy just be amongst us, without us even knowing it? - Cosmo: Maybe this is a test as well, to see whether we're altruistic beings or not. - Kasha: Are you saying the Ide is watching us? I think it's possible. But, for both us and the Buff Clan the people here can't represent an entire race! - Bes: Yes. But we do not know how to tell an entity made of hundreds of millions of life-forms, that goodness does exist. - Sheryl: It's true. The Ide can only watch us. I wish to draw your attention to three things: a giant robot that may be a higher evolved life form than the humans supposedly controlling it; the harvesting of a vast energy source from the wills of deceased consciousnesses - an energy source that defies entropy at that; and the misery of characters whose only prospects are undeserved annihilation. The genesis of Evangelion and Puella Magi Madoka Magica lies right here. Futher comments: The ideas are interesting, the concept of killing every last character singular (at least in 1982), and its bequests to later anime profound, but the films have hurdles to jump, particularly A Contact. Compressing 800 minutes of the TV series into 85 minutes of film was never going to work. I first watched the films about 7½ years ago, long before my recent, first viewing of the TV series. Back then, I found A Contact bewildering. Consisting of a highly truncated summary of the initial contact with the Buff Clan along with the inaugural flights of the Ideon and the Solo Ship, before moving into highlights of the many battles between the warring parties, the film gives no mind to character development or plot niceties. I could make neither head nor tail of who was supporting who or why anybody was doing what they were doing. The characters seemed little more than faces in a sequence of action set pieces. Under the circumstances I rated it as weak. The point is, it isn't setting out to be a coherent film. Released on a double bill with Be Invoked - the real reason fans were turning up at the cinema - treating it as an extended recap episode would be more appropriate. With eighteen months passing by since the TV series wound up, fans out for a proper resolution to the story would have appreciated its memory prompting role. Although I still wouldn't rate it highly, I appreciated it after only one month's gap since watching the TV series.

Right: Karala looking uncannily like Balsa (Moribito - Guardian of the Spirit). Importantly, It sets the relentless, doom-laden tone that is characteristic of the sequel. Be Invoked is counter-intuitively more powerful on subsequent viewings. First time around the viewer doesn't know what's happening beyond the film's reputation. And if the viewer had seen the TV series, then it soon enough moves beyong the truncated ending that spoiled the series' impact. Even then, the desperate struggle of the combatants to make sense of their predicament while trying to avoid annihilation is gripping. The moment the humans sought shelter in the Ideon and the Solo Ship, their fate was sealed. Trapped in a fight or flight pattern of behaviour they are unable to see their way through their dilemma. To relinquish infinite power is to cede it to those, both human and Buff Clan, who would use it aggressively. Retaining the power leaves them open to continuous assault that not only compels them to fight reluctantly, but will surely destroy them in detail. Doba, the supreme military commander of the Buff Clan, comes to a more rational conclusion: the Ideon and the Solo Ship must be destroyed at all costs for the sake of any who may survive the resulting apocalypse. Any other option entails total annihilation. Oddly enough, I find the tragedy quite bearable, unlike, say, Barefoot Gen or Grave of the Fireflies, which, despite their merits, discourage re-watching thanks to their grim presentation. Be Invoked is similarly grim but the otaku-centric visual style constantly reminded me that I was watching something artificial. The dryness of the characterisations - see my comments in the TV series review - also meant that I remained detached as the players were killed off in turn. In addition, the very reputation of the franchise has diminished the many deaths by turning them into a fan-centric circus show. I'm guilty myself in this post with my lovingly re-created decapitation of Ashura. We fans have transformed the deaths from tragedy to spectacle. And finally, the upbeat ending, even if utterly fantastical, is an antidote of sorts to the tragedy. I must give a special mention to the ponderous, yearning and yet grandiose death and rebirth musical theme, To the Cosmos used in later scenes. This gives way to the equally appropriate delirium of the Carl Orff and Vaughan Williams inspired Cantata Orbis in a visually distorted live-action sequence that owes much to 2001: A Space Odyssey. The on-screen activities may be cheesy, but the music lifts the film beyond its limitations. Karala Ajiba: In some ways Buff Clan Karala becomes the pivotal character of the series. Her liaison with human Bes Jordan should be a pointer for all the other characters. The conflict between the humans and the Buff Clan is predicated on the insistence of difference between them. The Karala / Bes and the Sheryl Formosa / Gije Zaral relationships prove otherwise. The humans are too pre-occupied to see what's staring them in the face, while the Buff Clan are too affronted. The fruit of her relationship is the child Messiah, whose role as guide reinforces Tomino's utopian, dare I say hippy, message that love and harmony are imperatives we must adopt for the sake of our future. Karala's worth lies in her natural curiosity, her principled decisions, and her determination to chart her own course. The writers avoid the common anime trap where love reduces the female to little more than an appendage of the male character. That said, her role, ultimately, is to become the vessel for her male child, whose very name suggests she is the Mother Mary figure to the coming saviour - important but subsidiary nonetheless. Still, her qualities, in spite of her humourlessness (though she's far from the only one), meant that she was my favourite character of the franchise. (My next favourite is probably Doba: initial dislike in time changing into begrudging admiration.)

Right: Sheryl Formosa in a positive frame of mind. Sheryl Formosa: Sheryl is the modern woman, brought undone by her ambition. A sour disposition (constantly exacerbated by a flying blue amphibian that seems intent on mocking or tormenting her - see image at the top of the post) makes her less than appealing, despite her considerable capabilities. Her affair with Gije is de-emphasised in the movies, no doubt due to time constraints. Gije gets much less relative screen time and, in any case, not only is their relationship but a variation on Karala's and Bes's, they don't produce any issue, so to speak. Unlike Karala whose role is essentially positive, Sheryl is a tragic figure. As the intellectual leader of the Logo Dau runaways she is the one expected to solve the mystery of the Ide. Instead, her realisation that the Ide will likely detroy everything will break her. Hysterical, her final act is to expose the uncomprehending child Piper Lou in the midst of battle in order to prompt the Ideon into action. The career woman becoming the mad woman just doesn't work for me. You may see it othewise. Ratings: The Ideon: A Contact: not really good. A disjointed, episodic recap of the first 32 episodes (or thereabouts) of the original series that's only worth watching for the last seven minutes, which provides a good breakdown of the dilemmas facing the humans controlling the Ide power. It may be handy if you need a reminder of what happened in the TV series before watching the sequel. The Ideon: Be Invoked: very good. A startling, gripping and thought provoking conclusion to a franchise that inexhorably ramps up the horror and desperation of the characters' situations, before resolving into a blissful, mystical flight of fancy. Despite the notorious death of every single character the film leaves the viewer on a high. How manufactured or appropriate the uplift is will be determined by the viewer. While I was moved, the cheesiness of the finale brings the score down somewhat.

Right: Karala sends forth Messiah. How to watch the Ideon franchise: I'd recommend watching all of it, but if you want to avoid the "wrong" ending of the TV series and the worst of A Contact, I'd suggest the following. 1. The first 32 episode of the TV series. 2. The last 7 minutes of The Ideon: A Contact. 3. Return to the TV series and watch up to the moment Karala and Joliver are teleported from the Solo Ship (4 minutes into the last episode, including the credits). 4. Start The Ideon: Be Invoked from the same moment (6½ minutes into film). Resources: ANN: The Ideon: A Contact; The Ideon: Be Invoked The font of all knowledge Ideon at Counter-X

Happy starchild. Blink and you'd miss the image when it appears. **** It may be 2-3 weeks before the next review. I've got a couple of 40-odd episode anime to watch. Last edited by Errinundra on Mon Feb 14, 2022 3:34 am; edited 4 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

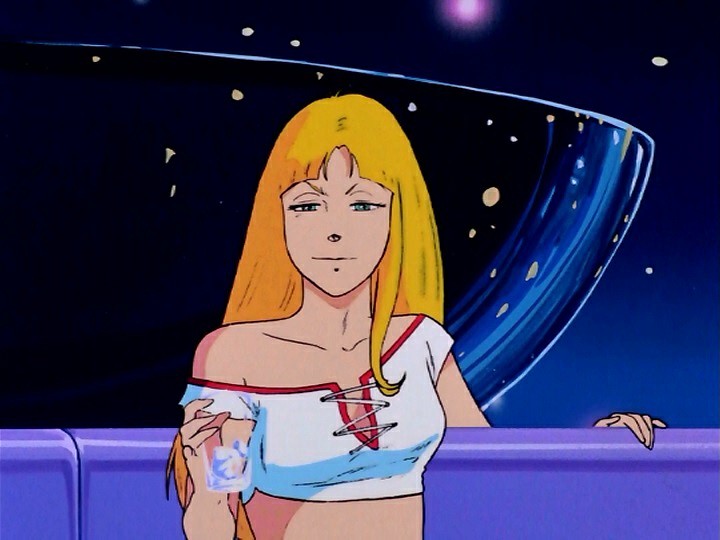

Splash (or more accurately, Gush) of Crimson #18, Lynn Minmay and Misa Hayase, et al

The Super Dimension Fortress Macross

Synopsis: Misa Hayase is the first officer of the Macross - a mighty spaceship come giant robot rebuilt from the remains of an abandoned alien craft that crash-landed on earth some years earlier. On the day of its launch another alien civilisation, the endlessly warring Zentradi who are investigating the fate of the ship, attacks earth. The crew of the Macross, in their haste to escape, accidentally teleports the spaceship, along with tens of thousands of civilians, to the far side of Pluto. There begins a cat and mouse game as Hayase and her comrades, led by Captain Bruno J Global, keep the warrior Zentradi at bay while trying to find a way back to an earth that dreads their return. Among the civilians on board are acrobatic pilot Hikaru Ichijyo who becomes an ace fighter for the Macross (all the while driving Misa Hayase spare with his unconventional attitude) and wannabe pop-singer Lynn Minmay, who quickly becomes the heart and soul of the Macross with its many homesick refugees. When video clips of Minmay's songs such as My Boyfriend is a Pilot are infiltrated among the rank-and-file Zentradi soldiers the effect is seismic. Preferring the proffered fantasies of an idol singer to a life sentence of warfare, the Zentradi forces crumble before Minmay's kawaii assault. As these apocalyptic events unfold Hayase realises that she has fallen in love with Hikaru. But how does a straight-laced, uptight, career military woman compete with something like Minmay? Production details: Premiere: 03 October 1982 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #32, Minky Momo, and Beautiful Fighting Girl #33, Ranze Etou) Director: Noboru Ishiguro (Space Battleship Yamato and sequels, Megazone 23 and sequels, The Legend of the Galactic Heroes franchise among other things) Studio: Studio Nue with the assistance of Tatsunoko Productions, Artland and others. Series Composition: Kenichi Matsuzaki who had a hand in the scripts for both Gundam and The Ideon. All three have a similar framing story of a space battleship adrift, abandoned and beset by enemies. The same narrative elements propel both Space Battleship Yamato and GoShogun (though Kenichi Matsuzaki wasn't involved in either). Music: Kentarō Haneda Character Design: Haruhiko Mikimoto Art Director: Kazuko Katsui and Kikuko Tada Mechanical design: Kazutaka Miyatake and Shoji Kawamori. The latter became the creative force behind later Macross iterations as well as The Vision of Escaflowne, Arjuna, Aquarion and AKB0048 among other things. His mechanical designs permeate anime from the 1970s to the present. Note: You can read my original review of the series here. Given that it has only been two years I won't review it again. Rather, I'll make some brief comments about a couple of aspects of the series before looking at three of the female characters in more detail. The post is written within the context of the overall beautiful fighting girl project so please be aware that there's more to the series than is presented here.

SDFM introduces the harem to the project, though not quite in the form we are familiar with today. The main harem revolves around Captain Bruno J Global (centre). Clockwise from top left: First Officer Misa Hayase; Navigation Officer Claudia La Salle; airhead Shammy Milliome; Kim Kabarov; the highly stressed pinpoint barrier team (May, Panapp and Pocky as you continue around); and Vanessa Laird. Comments: When I first watched SDFM two years ago I came to it with expectations that it would be a sententious action series with mecha, spaceships, brave soldiers and overwrought romance in the style of Gundam or Space Battleship Yamato. While those elements are an essential part of the package I soon realised that something more interesting was going on. Given my pre-conceptions, when Captain Global first bangs his forehead on the bulkhead doorway onto the bridge the tonal effect is jarring (in more ways than one). The girly bridge crew then had me scratching my head. By episode nine, as the first Zentradi fighters are going ga-ga over transmissions of Minmay in a bathing suit, I was in no doubt that this wasn't the straightforward anime I thought it would be. This time around, fully aware that the series is a nudge-nudge-wink-wink piss take on the contemporary sci-fi and mecha formula (of which I'm now more knowledgeable), I was able to assess it on its own terms from the get go. Funnily enough, this isn't a parody in the style of GoShogun, which stands outside the mecha conventions of the time and laughs at them, albeit cleverly and affectionately. No, SDFM is knowingly and closely connecting with its otaku audience. The viewer is aware that the creators are aware that they live together in a sort of entertainment ecological niche. In important ways the otaku viewer is the subject of of the series, not Hikaru Ichijyo nor Misa Hayase nor Lynn Minmay. Daicon III introduced the approach a year earlier; now SDFM brings it to the TV screen with all its durability and accessibility. Like Daicon III, it presents as an artefact for a in-group to claim as their own. Unlike Daicon III, broadcast availability allowed it to expand the very audience it was feeding (and feeding off). With the voracious yet ironic male otaku viewer the raison d'être behind the production, servicing their expectations becomes paramount. Hence the mecha, spaceships, brave soldiers and overwrought romance. An intriguing fanservice innovation is the introduction of the harem to anime, ten years before Tenchi Muyo! Ryo-Ohki, though not yet with all the tropes we are so familiar with today. Three harems can be identified. The first, and largest, surrounds Captain Bruno J Global, as shown in the image above. This is largely played as a gag: feminine chatter, gossip and emotional over-reaction have commandeered the traditionally masculine, military space of a battleship bridge. While the development undermines any militaristic posturing, no feminist case is being made. The purpose is to amuse the male viewer via the women's clownish behaviour and gendered depiction. Only Hayase and Claudia are given any roles beyond their place within the harem. For his part, Global treats the women with a gruff paternalism, thereby reinforcing the privileged position of the male player as well as the male viewer. The second, smaller, harem involves the protagonist Hikaru, his competing love interests in Minmay and Hayase, and, to a much lesser degree, Shammy, Kim and Vanessa (who dismiss him out of hand). A third harem, as illustrated by Claudia to Hayasa as a reflection of Hikaru's, is Roy Fokker's flotilla of girls, with whom Claudia must compete. SDFM succeeds with its harems thanks partly to the good-natured humour, but also because the depiction of its female characters is affectionate, unlike the earlier Go Nagai series I've reviewed, including Cutie Honey, where the women are treated, for the most part, spitefully.

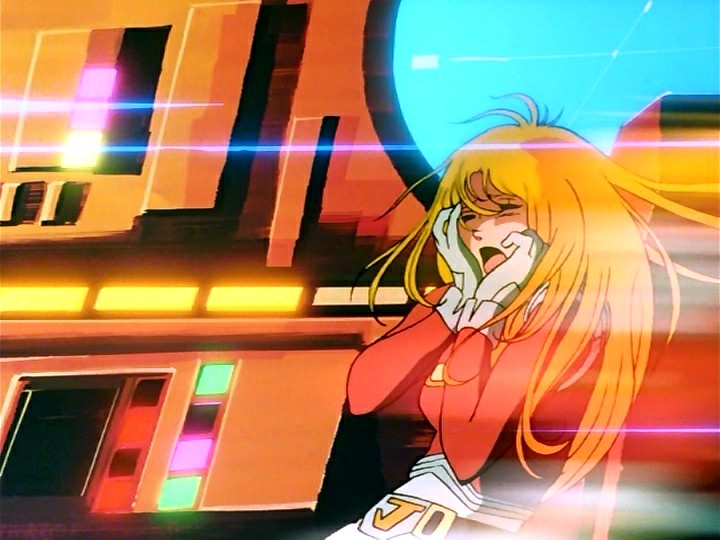

Milia mortifera (sinister) et Minmay hospita (dexter). Don't be fooled by appearances: they are each a weapon of mass destruction. Lynn Minmay (perhaps more correctly, Minmei): While Hikaru Ichijyo is the protagonist and point of view character of SDFM, Minmay, as the embodiment of proto-culture, is the story. As I've assembled my collection of beatutiful fighting girl anime I've noticed that this bifurcation between protagonist and premium character is a common set-up within the genre, from Armitage III to Burst Angel to Shakugan no Shana to Claymore, to give some examples. But, more on that another time. Minmay is the most original element of Macross and will be the foundation of one the franchise's characteristic features - the idol singer. As such, she is intimately linked with not only her on-screen fans living within Macross, but also with her real life otaku fanbase, thereby neatly illustrating my argument above: she is created to be possessed by the real subject of the series, the otaku audience. What's more, like Junko Fujiyama as Nozomi in Wandering Sun and Takako Ota as Yuu Morisawa / Mami in Magical Angel Creamy Mami, singer / seiyuu Mari Iijima will spawn a successful idol career thanks to her exposure in the anime. Minmay also embodies one of the most appealing features of SDFM: it's apocalyptic absurdity. Her cuteness, her sexiness, her songs of promised love will lead to the extinction of the Zentradi race. (The few survivors will be assimilated with the remaining humans.) The underlying theme of "make love, not war" is both subversive and deliciously enticing for Zentradi and viewer alike. I suppose you could say that, from the human point of view, making love will win the war. It's a credit to the creators that such disparate elements as armegeddon and idol singers, warfare and intimacy, battle fleets and harems, or epic theatre and absurdity, can be blended so seamlessly. Milia Fallyna: Milia is the greatest of the Zentradi warriors, akin to Trojan Hector or Greek Achilles and many other legendary or historical figures. (It just occurred to me: Minmay is the Zentradi's Trojan Horse. How cool!) As Hector met his match with Achilles, so Milia will be conquered by the human champion Maximilian Jenius. First of all, given the different sexes of Hector and Milia, and the thematic pre-occupations of SDFM compared with The Illiad, conquering has different connotations in the two cases. Hector will be killed; Milia seduced (though not without a fight - literally). Secondly, who is Maximilian Jenius, the human champion who can best Milia on the battlefield, in a knife fight and in the game arcade? He is skinny, bespectacled, lank-haired and a geek. In other words, he is the representation, or even parody, of the otaku fan. He gets the girl nonetheless, and Milia's an impressive one at that. What's more, theirs is the most natural seeming of the various romantic permutations explored in the series. Milia never loses her dedication to her chosen career path - killing people - and continues fighting (though by now she has switched sides) even as a mother. Her simple solution to her child-minding dilemma is to take her baby into battle with her. As I mentioned in my review, I'm sure that the baby-in-the-battle scene is a direct riposte to Ashura's last moments in The Ideon: Be Invoked. (I've posted pictures in the review.)

Milia battling Maximilian Jenius - in a game arcade. Misa Hayase: I've saved the best till last. Hey, you don't need to believe me: she won the Animage best character award in 1983. Just as SDFM isn't quite a harem show, Hayase has elements of a tsundere (even if the term hadn't been invented at that point), being preceded by Lum from Urusei Yatsura and pre-dating Madoka Ayukawa from Kimagure Orange Road. Hayase isn't capricious, but she does give Hikaru grief from time to time, escpecially early in the series. (Him calling her an old woman certainly doesn't help matters.) The thing to note, though, is that Hayase has an important relationship not only with the protagonist, but also with the viewer. Like Minmay, she's proto-moe. Despite her intelligence - she's the best tactician on the Macross - and her surface self-assurance I frequently had the feeling that circumstances were giving her a raw deal, and that she wasn't quite up to romantic warfare with Lynn Mimnay. That's something of a moeru response and, hence, I found myself shipping her, rather than Minmay, with Hikaru. Negima mangaka Ken Akamatsu said this of moeru, "The person feeling it must be stronger: the object of “moe” is weak and dependant (like a child) on the person, or is in a situation where she cannot oppose." Hikaru will save her and Minmay multiple times. Happily Hayase is something more than just a moe object for the subject viewer. With her serious outlook, her smarts, her authentic behaviour and her occasional unintended clownishness (a trait shared to varying degrees with every single character in the series) Hayase is a more otaku-oriented version of Sayla Mass from Mobile Suit Gundam and a harbinger of future beautiful fighting girls. Rating: Given how well Super Dimension Fortress Macross stood up to a second viewing I've increased it to very good. To quote myself from the earlier review, "The whole thing is deliriously absurd yet the series gets away with it. SDFM nicely juggles its dramatic and absurd elements, partly for the reasons I gave above (ie, how it steadily escalates the absurdities to maintain coherence), partly because all the characters in the large cast have some degree of clownishness about them, partly because the battles are quite the spectacle, and mostly because of the three central characters." (Thanks, Zin5ki.)

I loved Misa Hayase's Irish appearance, the Princess Leia inpsired hair whorls notwithstanding. Resources ANN - I recommend this Answerman article about idol culture from Justin Sevakis The font of all knowledge The New Matthews Anime Blog, quoting Ken Akamatsu's online diary. Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Last edited by Errinundra on Mon Aug 16, 2021 5:18 am; edited 8 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Zin5ki

Posts: 6680 Location: London, UK |

|

||

|

↑

Heavens, I am unsure why credit was due, but you are most welcome nonetheless! |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

@ Zin5ki,

This post. Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Nov 27, 2020 2:10 am; edited 1 time in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Beltane70

Posts: 3969 |

|

||

|

I quite enjoyed your presentation regarding my favorite anime franchise and its female cast! The original Macross series was also my gateway anime (not including shows that were shown in the US before it, since I wasn’t aware of the term anime at the time), so it holds a very special place in my heart.

I look forward to seeing what you’ll be covering next! |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Thanks for the kind words.

More Tomino! |

|||

|

|||

|

Beltane70

Posts: 3969 |

|

||

I’m guessing Dunbine, perhaps? |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Splash (or rather, cascade) of Crimson #19: the many female characters of

Aura Battler Dunbine

Ciela Lapana, Queen of Na. I've chosen her to head the post as she's the most powerful of the regularly appearing women. Synopsis: Japanese motocross competitor Shou Zama is unwillingly sucked into another dimension - the mediaeval fantasy world of Byston Well - where his "Upper Earth" aura grants him exceptional capabilities when piloting mecha known as "battlers". That the mecha even exist, alongside gigantic floating battleships, is also due to transported Upper Earth humans, who have brought their modern engineering expertise along with their auras. Drake Luft, the man behind the inter-dimensional transporting using the magical powers of an enslaved silkie, builds an aura fleet to forcefully unify Byston Well, leading to an arms race involving its various kingdoms and factions. Rebelling against Luft, Shou joins a resistance group led by Neil Given who eventually allies with two queens, Ciela Lapana and Elle Humn. Angered by the aggressive behaviour of the humans - whatever their origin, Byston Well or Upper Earth - the queen of the silkies transports every last battler, warship and their combatants to Upper Earth, where now it's the Byston Well aura that is magnified stupendously. The inhabitants of our world can mostly only look on in stupified wonder as, unable to curb their instinct for war, the Byston Well factions race towards a final apocalyptic battle above the North Atlantic Ocean. Production details: Premiere: 05 February 1983 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #33, Ranze Etou, and Beautiful Fighting Girl #34, Yuu Morisawa) Director: Yoshiyuki Tomino Original creator: Yoshiyuki Tomino, Tominori Kogawa and Sunrise (under their pseudonym Hajime Yatate) Source material: Tomino's light novel series The Wings of Rean, which, oddly enough, doesn't contain mecha. Studio: Sunrise Music: Katsuhiro Tsubonou Script: Sukehiro Tomita and Yuuji Watanabe Character Design: Tomonori Kogawa Mecha design: Kazutaka Miyatake Art: Shigemi Ikeda

Protagonist Shou Zama with his constant battle companion, the fairy Cham Huau. Insert: Queen of the silkies, Jakoba Aon, and three of the insect inspired "battlers", with the titular Dunbine on the left. Comments: Tomino's original novels, upon which is the series is based, are set in a mediaeval European inspired fantasy landscape replete with castles, unicorns, fairies, silkies, druid-like priestesses and assortment of reptilian, slime and insectoid monsters. Sunrise and Bandai were amenable to making a TV series if it included mecha, so a compliant, if not happy, Tomino maintained thematic integrity by utilising mecha designs inspired by the aforementioned insects that, when still, are an improvement upon his earlier shows, what with their carapaces, wing covers and transparent wings. (In fact, the "battlers" are built from the bodies of the giant insects.) When animated, however, the curved body parts, the insect appendages, and uniform colouring (particularly the cannon-fodder rank and file soldiers) meant that I too often struggled to make out what a mecha was doing. The combination of Tolkienesque fantasy and mecha warfare not only pre-figures The Vision of Escaflowne by some thirteen years, but also provides considerable scope to appeal to a wider demographic than, say, either of Tomino's earlier Mobile Suit Gundam or Space Runaway Ideon. The gorgeous, otherworldly landscapes - somewhat reminiscent of the artwork of Roger Dean - make this easily my favourite Tomino setting. That said, the magical transportation of the warring fleets to our modern world two thirds of the way through is the dramatic turning point of the series, allowing Tomino to hammer home his gloomy view of the human race's inability to avoid destructive warfare. That means, in typical fashion, he will kill off large swathes of the cast. And, for once, the TV stations didn't pull the pin on his show prematurely, so that the last few episodes of ABD don't feel rushed. The oppressive doom-laden mood is steadily, deliberately ratcheted ever upwards, though the near non-stop battles do became a chore to watch at times. In fairness, I watched the entire 49 episodes over ten consecutive days, whereas the original broadcast would have spread the violence over the best part of a year. Under that viewing regime one wouldn't feel quite so bludgeoned.

Byston Well landscape. The series also suffers from characteristic Tomino shortcomings. First of all, his principal characters are devoid of wit. They are a uniformly dour bunch. Tomino follows the Toei practice of siphoning the humour through secondary gag players, in this instance mainly through the Mi Ferario characters, Cham, Bell and El. These comic relief fairies correspond to the mascot characters of shoujo anime. While Cham is, on balance, a positive addition to the series, Queen Ciela's Bell and El spoil any scene in which they appear, unintentionally and comprehensively undermining her supposed gravitas. GoShogun proved that anime can give us witty action heroes; Super Dimension Fortress Macross seamlessly transitioned its characters from heroic to absurd. Funnily enough, when Tomino took over directing The Star of the Seine (my favourite of his shows) around the half-way mark, he introduced a cheesy, sly humour to the mix, so he can do it. Secondly, episodes (or strings of episodes) can be heavy handed in their execution and repetitive in their structure. It isn't nearly as bad as the TV version of Ideon, while the detailed Byston Well world-building mitigates the problem somewhat. Lastly, Tomino plots can be directionless for long stretches, moving in fits and starts, and all the while leaving the characters reacting to events instead of shaping them. His fatalistic worldview that humans are incapable of resisting their self-destructive impulses may well exacerbate the problem, but great anime can be satisfying on a thematic and narrative level simultaneously. As I mentioned earlier the series shifts up a gear when the super-powered aura mecha and battleships arrive en masse on earth. (This is the oldest show I know where "powering up" is featured and discussed in story.) Australia is worthless (apparently koalas have rat-like tails and our deserts have cacti), Tokyo is trashed, Paris burned to the ground and the rest of western Europe cowed. Like all the Byston Well queens, the Queen of England proves herself heroic, while pretty much only Russia and America resist. The former get their nuclear missiles flung straight back at them, while the Americans have the good sense to side with one of the factions. The delicious irony is that we, the earth's population, are forced to bear witnesses and become victims to the very behaviour we are unable to restrain. We become collateral damage thanks to an alien personification of our own innate folly.

Paris burns. That's an aura battleship cruising above the Arc de Triomphe Although the characters may be earnest, ABD has a vast array who are both distinctive and interesting. None of the villains can match the charm of Gundam's Char Aznable, but their very earnestness means that the viewer is spared the evil laugh for the most part. Protagonist Shou Zama is, like his counterparts in Gundam and Ideon, a straigtforward, serious young man who somehow can't extricate himself from a fight. He'd be totally dull if not for his early incomprehension in the face of his summoners' iniquity, his inept, wooden responses to romantic interest Marvel Frozen, or Cham's behaviour humanising him. (And, yes, Aura Battler Dunbine is the apotheosis of stupid anime character names. Along with Marvel Frozen there's Shot Weapon, Drake Luft, Keen Kiss, Neil Given, Bishott Hate, Galeria Nyamhi, Musy Poe, El Fino and Zet Light to list the best of them. Don't ask me how a redheaded Belfast woman could be baptised Jeril Kuchibi. I would add also that there doesn't seem to be any canonical way to spell or even say many of the names.) The big bad, Drake Luft - a bald-headed variation on Ideon's Doba Ajiba - is yet another humourless character. His ruthlessness is tempered by the gnawing suspicion that he may genuinely be working hard for the benefit of the people he rules. Like Ajiba Doba he has a daughter who, objecting to his methods, defies him. The big difference is that he somehow manages to retain a soft spot for her in his heart. That helps redeem him in this viewer's eyes. Aura Battler Dunbine may be a pinnacle of stupid names, but, more tellingly, it has the best ensemble array of female characters so far in this grand survey. Sure, Maetel and Oscar surpass them on individual comparisons; sure, the protagonist is male; and, sure, their designs are, for the most part, intended to please the male viewer, but, grunts aside, they appear in pretty much equal numbers as the men amongst all the factions and, protagonist aside, in importance to the story. The final cataclysmic battle pits two battlefleets commanded by men - the big bad Drake Luft and his rat-cunning confederate Bishott Hate against two battlefleets led by Queen Ciela Lapana, with her enormously expanding aura powers, and Queen Elle Humn. Silkie queen Jacoba Aon's banishing of all the combatants from Byston Well pins her as the most powerful character until Ciela brings the war to its ultimate conclusion. By this point Shou Zama has been rendered superfluous. Although it's as if there's a smorgasboard of female characters to appreciate, much as with Super Dimension Fortress Macross, I believe something else is beginning here. At least some of these characters elicit a degree of admiration from the male viewer, though there's still a way to go before the connection of male viewer identifying with female protagonist is made.

Fighting women of Aura Battler Dunbine The women (left to right) Top row: Elle Humn. The granddaughter of King Phaezon of Lao, when we first meet Elle she is more interested in the mystical powers of Byston Well than politics. After her father is killed in battle she reluctantly takes command of his forces against Drake Luft. Her affinity with the sacred makes her a powerful aura commander. Elle's journey is from the domestic and spiritual to the public and military realms or, if you will, from the feminine to the masculine. It is something she accepts rather than chooses. Ciela Lapana. A steadfast character who does what she does because it is right to do so, Ciela will ultimately become the most powerful aura user. Her final act that concludes the story, and which is a variation on the earlier banishment of the warmongers from Byston Well, indicates that she has taken the mantle of final arbiter from silkie queen Jacoba Aon (whose act meant the sacrifice of her own life). This makes her, thematically, the key character of the anime. (Oh, and the fairies in the image are the dreadful Bell and El.) Middle row: Marvel Frozen. Raised on a Texas farm before her summoning to Byston Well she is the best "battler" pilot of Neil Given's resistance force against Drake Luft until the arrival of protagonist Shou Zama and the catalyst for his change of heart. Their's will be the chief love interest of the series. So, while her role defines her as adjunct to the male, she is strong-willed, otherwise independent, and capable. Unlike so much other anime, her romantic involvement does not diminish her personality. Keen Kiss (or Keats in some souces). Tomboy "battler" pilot in Neil Given's resistance force aboard his flying ship Zelana, she lacks the innate abilities of Frozen or Shou so overcompensates by fighting rashly. Keen personifies Tamaki Saito's phallic girl to the extent that she has cast aside feminine traits idealised elsewhere in 1980s anime such as Magical Angle Creamy Mami. Riml Luft. Naturally enough, the daughter of the big bad and the evil mother will be the lover of the leader of the resistance force, Neil Given. You'd expect that sort of thing in an epic yarn. Her father keeps her under house arrest for, he supposes, her own good. The funny thing is, after several failed attempts by Neil and Shou to rescue her (or abduct her, depending on your point of view), she has to do it on her own. Bottom Row: Galeria Nyamhi. Near psycopathic "battler" pilot in the Drake Luft forces, she is motivated by a lust for glory and, after repeated defeats in battle against Shou Zama, an overwhelming desire for payback. As an unhinged phallic girl, she volunteers for ever more outrageous fighting missions to achieve her goals. In her own way she is subordinated to Shou, defining herself against him. Musy Poe. Begins as Riml Luft's music teacher. Her love for the ambiguous American engineer Shot Weapon, summoned to Byston Well by Drake Luft, brings her into the war as a "battler" pilot. Despite being submissive to Riml, Drake and Shot in turn, she is one of the few decent characters amongst Drake's forces. Jeril Kuchibi. Born and raised in the tenement slums of Belfast , Jeril concludes that life as a "battler" pilot in Drake's army is much preferable. Is she pissed off when Jacoba Aon trasnports her back outside her childhood home (though sitting comfortably in her aura battler), or what? A complete cynic, she's out to look after herself and if that means fighting a war of little interest to her or sticking with the big bad because he's the likely victor, then so be it. Rating: Good. Aura Battler Dunbine stretches the boundaries of how far an anime can develop autonomous female characters for a mostly male audience, though it may be argued the anime is also hoping to expand its female audience. The detailed world-building of Byston Well gives the setting more depth and appeal than Tomino's two previous franchises, and he has more space to properly prepare the viewer for his epic and explosive climax, however the characteristic earnest characters, pessimistic take on human nature and attenuated narrative style remain. Resources: ANN Terminal Tomiosis from the Mike Toole Show The font of all knowledge Aura Battler Dunbine at Super Robot Wars Wiki Aura Battler Dunbine archived from The World-Wide Gundam Informational Network The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle

Notice how Frozen is taller than Shou? Last edited by Errinundra on Mon Aug 16, 2021 5:22 am; edited 4 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Splash of Crimson #20: Alfin, Princess Royal of Kingdom Pizanne

Crusher Joe Synopsis: Alfin is a runaway princess acting as navigator on the spaceship The Minerva, captained by Crusher Joe. In 2161 Crushers can be relied upon to take on the tough jobs across the galaxy. They have a strong code of ethics, so when Joe is accused of piracy after their cargo - a cryogenically frozen heiress - disappears mid space warp, he and is crew on the Minerva lose their operating licence for six months. With clandestine assistance from the United Space Force and a politician who's up to more than he's letting on, Alfin, Joe and their crew mates set out to find their missing cargo. This leads them to notorious space pirate, Big Murphy. Production details: Premiere: 12 March 1983 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #33, Ranze Etou, and Beautiful Fighting Girl #34, Yuu Morisawa) Director & character design: Yoshikazu Yasuhiko - has spenct most of his long anime career as a character designer, especially with the Gundam franchise, but also directed Giant Gorg, Arion, Venus Wars and the boy's love anime Kaze to Ki no Uta SANCTUS -Sei naru kana- Studios: Studio Nue & Sunrise Source material: Haruka Takachiho's light novel series Crusher Joe, published from 1977 to 2005. Takachiho also wrote the Dirty Pair light novels and was a co-founder of Studio Nue. Screenplay: Haruka Takachiho and Yoshikazu Yasuhiko Art Director: Mitsuki Nakamura Animation Director: Norio Kashima and Yoshikazu Yasuhiko Mechanical design: Shoji Kawamori Art design: Michiaki Sato Music: Norio Maeda

The crew of the Minerva sans Dongo the robot. Left to right: Talos, Ricky, Alfin and Joe. Note: This is another revisit. You can read my review from 10 September 2016 here. In my conclusion to that review I speculated I would never revisit the film, but time makes a mockery of us all. Not only have I watched, and enjoyed, it again, I'm now the owner of Discotek's DVD issue. As with Macross I'll make some brief comments and then look at Alfin in more detail. Comments: Watching Crusher Joe again after two years not only reinforces its debt to Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark, but the crew of the Minerva (Joe, Alfin, Talos, Ricky and Dongo) constantly reminded me of the crew from Cowboy Bebop (Spike, Faye, Talos and Ed with the corgi Ein replacing the robot Dongo). My strong feeling is that the creators of the newer anime used Crusher Joe as a template for Cowboy Bebop's inventive riffing on the theme of maverick business operators in space. There's no plagiarism involved here: CB explores themes and characters in altogether different ways compared with its older inspiration. And, of course, replaces a bombastic faux-Hollywood soundtrack with Yoko Kanno's memorable jazz inflected numbers. Stepping back into Crusher Joe's own era, it was part of the anime science fiction new wave in the wake of the enormous popularity of Star Wars, alongside other titles I've covered as part of the project: the Space Battleship Yamato movies, Galaxy Express 999, Mobile Suit Gundam, Super Dimension Fortress Macross and GoShogun, and some I haven't, such as Space Adventure Cobra. Like most of the others - Tomino's mecha series are the notable exception - Crusher Joe's tone is marked by its tongue-in-cheek humour and its frequent use of sci-fi action tropes. That said, while it happily exploits said tropes, this is in no way a parody in the manner of GoShogun or a knowing fan-focused romp like Macross. It's a straightforward anime without any major message, self-aware cleverness or emotional investment from the viewer. The film must rely on its verve, its non-stop derring-do action and its goofy comedy to keep the viewer's interest over the rather long viewing time of 132 minutes. (Anime movies of the era were very generous.) Judged by those parameters Crusher Joe is largely successful. Character appearances, spaceship designs and futuristic architecture are conventional for anime of the time. Joe not only shares his name with many contemporary heroes, he looks like all of them to boot. That's not to say the animation and artwork aren't good - in particular, the actions sequences are lively and detailed. Japanese stylistic conventions aside, the influence of American movies permeates throughout. If the big set piece scenes owe much to Star Wars, then the willing embrace of B Grade movie cliches shows the influence of Indiana Jones. Indeed, Joe is Indiana Jones light in a sci-fi setting, though he lacks the American's more self-aware ironic overlay. He's a comic character precisely because he doesn't know he is. In that sense he owes a little to Luke Skywalker.

Alfin: for every subversive demonstration there's an act of conformity. Alfin: The rebellious Princess of Kingdom Pizanne also calls to mind American big screen heroines of the time. Her back story, feisty character and sparring with Joe are clearly referencing Princess Leia, including the latter's relationship with Han Solo. More proletarian than princess, she entirely lacks Leia's aura of authority. Instead of meeting her in the corridors of power, or participating in a military de-brief, Alfin seems the sort of young woman I'd expect to meet in a suburban beer barn on a Saturday night: out to get pissed, have a rollicking time, listen to a band, get into a stoush, and suffer the consequences the morning after. As it happens, she does precisely those things in her most memorable sequence in the film (see middle left in the picture above and also the image at the top of the post). She's gritty and rough and, for the most part, highly competent, though not the sharpest needle in the sewing basket. The catch is, she is not only secondary in importance to Joe, she is the cheesecake female tethered (admittedly willingly) to the male and whose main purpose is once removed gratification for the viewer identifying with the protagonist. She clings to Joe in a crisis (despite repeated demonstrations of her courage), is helpless when he saves her (despite repeated demonstrations of her capabilities), throws tantrums when she thinks he's eyeing off another woman, and it is she who embraces him when they are re-united. In addition, she has a proto-moe tsundere nature that accentuates her weakness. But wait, there's more: she's frequently treated as a clown, undermining her credibility yet further. Yes, she's a fun character, but a very traditional one for all that, even with her layers of anime tropes. Haruka Takachiho would improve the mould with Dirty Pair. Yuri and Kei will blend Alfin's mixture of courseness, competence, clownishness and gleeful violence, then add an insouciant fourth wall breaking camera awareness before topping things off by playing second fiddle to absolutely nobody. Their drive-in theatre cameo in Crusher Joe is but a harbinger of things to come. Rating: Still at the lower end of good. What price can be put on unadulterated fun? LIke most anime of the time, becoming acclimated to the visual style is something of a pre-requisite to enjoying the anime on its terms. Having immersed myself in the era I'm no longer bothered by the seeming peculiarities. Once past that hurdle, the film will reward with its exciting, well animated action sequences and its mostly clownish cast. Resources: Crusher Joe: the Movie, Discotek ANN (recommended reading: Justin Sevakis's Buried Treasure article) The font of all knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle

Last edited by Errinundra on Mon Aug 16, 2021 5:28 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

nobahn

Subscriber SubscriberPosts: 5146 |

|

||

|

I've been neglecting the Anime with Strong Female Leads/Co-Leads? recommendations thread. I say that to segue to the following YouTube video I've found that deals with Magical Girls:

"Why There Are Magical Girl Transformations In Anime" by Get In The Robot It's pretty good; but I can't decide whether or not to post a link in the Strong Female Leads/Co-Leads thread. What do you think? |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Go for it!

(Though she totally lost credibility by not mentioning Princess Tutu.) |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6580 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

It's not quite a new year and not quite a new page, but after almost two years, and now that I've completed the Splash of Crimson sidetrack, it's time to check out where we're at.

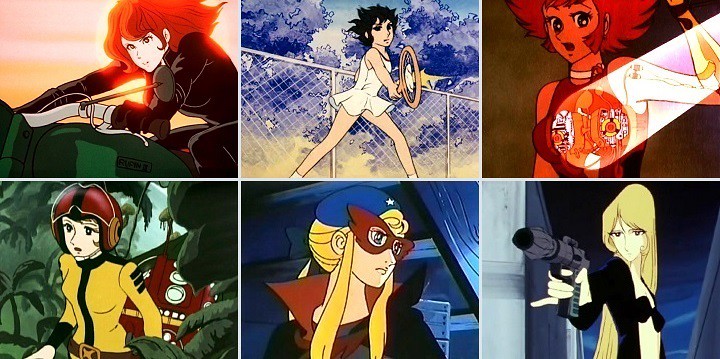

Anime's Beautiful Fighting Girls Recap Episode

This survey has shown me that, before the rise of the otaku in the late 1970s, the evolution of the beautiful fighting girl can be observed in four disparate strands. First, Toei's initially innovative then, later, more formulaic - with one notable exception - magical girl series. Second, Mushi Pro and its successor studios expandiing the magical girl genre beyond Toei's limited settings into shojo TV series and offbeat flims where the female heroine finds herself in a greater variety of roles and circumstances than ever before. Third, the rise of World Masterpiece Theatre type shows and films, again with clear links to their magical girl antecedents, that aimed for a wider audience. And, last, the increasing sophistication of female characters in shonen anime, mostly as secondary players, but sometimes giving us outstanding and memorable characters. Naturally enough there is some cross-over between the threads and, also, eccentric examples that defy classification. As I child of the 60s - I had the good fortune to watch Astro Boy, Gigantor and Kimba the White Lion on their original western release when they were age-appropriate for me - and a teenager in the 70s (the character in the Monty Python image above might just be a parody of me today), my memory informs me that western children's TV shows of the time rarely, if ever, had female protagonists. I can't think of one off the top of my head. My speculation - and I don't think its outrageous - is that, with anime evolving from manga where shojo titles were as successful as shonen ones, Japanese TV companies weren't as nervous as their Anglophone counterparts when it came to giving us female protagonists. Beautiful...

Top (l-r): Bai Niang, The Tale of the White Serpent; Françoise Arnoul / Cyborg 003, Cyborg 009; and Sally Yumeno, Sally the Witch Bottom: Sapphire, Princess Knight; Kathy Flint, Animal Treasure Island; and Nozomi Mine, Nozomi in the Sun Looking at the strands in more detail, the wellspring of the beautiful fighting girl is to be found in the Toei canon, beginning with Bai Niang, the titular character of The Tale of the White Serpent (1958). She is magical, demonic, enigmatic yet loyal and sets the tone, if not aesthetic standard, for many a magical character to come. The first magical girl TV show, Sally the Witch (1966) was famously inspired by the American TV show, Bewitched, and featured a schoolgirl witch from the magical realm who must contend with the Japanese education system and assorted bad guys who cross her path. Their next offering, Secret Akko-chan (1969) flipped the setup by having the protagonist a regular girl who gains transformational powers with a magic mirror. Every magical girl since is one or the other or a blend of the two prototypes. These early shows are simple, geared to a young audience, episodic and ripe for merchandising. They are largely formulaic, other than gimmicks around their identity - there's a mermaid, a couple of androids, a super-powered ninja and a variation on a doppelganger as examples - and the occasional exploration of uncomfortable topics such as family disfunction, suicide and environmental degradation. The most innovative by far was Cutie Honey (1973) which introduced many of the tropes we take for granted today in the genre. It's a shame it's such a crappy show. Aimed at a male audience, many of those tropes were lifted straight from the super robot shows of the time (Go Nagai was the creative force behind both Cutie Honey and the tranforming giant robot). If the magical girl was the genesis of the beautiful fighting girl, then you could equally say that, without Mazinger Z (via Cutie Honey) there could be no Sailor Moon. Lunlun the Flower Child (1979) upgraded the aesthetics of the genre while transposing the setting to Europe but otherwise largely conformed to the formulae of its predecessors. Subsequently Toei lost interest in the genre. By the end of the period under examination Studio Pierrot had taken over Toei's mantle, broadcasting Magical Angel Creamy Mami (1983), the first of several combining the genre with idol stardom. The priceless gift that Toei bequeathed us is an autonomous heroine with her own agenda who triumphs over adversity and who garnered a suprising level of cross-gender appeal. The 60s were also the golden years of Osamu Tezuka's Mushi Pro, the other studio to play an indelible role in the genesis of the beautiful fighting girl. After some early experimental films followed by more popular TV fare with male protagonists he produced the groundbreaking Princess Knight (1967) which added a level of sophistication to anime unimaginable in its contemporaties. Utterly self-aware, the series makes the arrival of the female protagonist in anime a central theme of its fantasy setting. The girl must pretend to be a boy to succeed in a world of narrow expectations. Her ultimate triumph as a girl becomes a metaphor for the anime industry itself. Emboldened, he made another, peculiar magical girl show, Marvellous Melmo (1971) that was too often an indulgent exercise in expounding Tezuka's humanist worldview. Fine sentiments but audiences hated its pedagogic tone. The studio also attempted to chase an older audience with the films Cleopatra (1970) and Belladonna of Sadness (1973) where the magical girl is replaced by an adult witch. Both bombed in theatres, though the latter is a striking film if watched without normal anime expectations. Mushi pushed the boundaries in another direction with Nozumi in the Sun (1971) about two pop singers who, unbeknownst to them, were swapped at birth. With the collapse of Mushi, staff founded two studios - Madhouse and Sunrise - that continued the Mushi tradition, but with a rigorous business approach. The former produced Aim for the Ace! (1973) while the latter gave us the unjustly forgotten Star of the Seine (1975). The crowning glory, so to speak, of this lineage and for beautiful fighting girls generally in the seventies, would be the Rose of Versailles (1979), although Toei's Galaxy Express 999 (1978) gives us an equally commanding female character in a marginally inferior package. Oscar and Maetel stand astride the era, clearly owing a debt to their predecessors but having more in common with the women who will follow them in the decades to come. Trailblazers and great characters by any measure. ...fighting...

Top: Fujiko Mine, Lupin the 3rd; Hiromi Oka, Aim for the Ace!; and Honey Kisaragi, Cutie Honey Bottom: Yuki Mori, Space Battleship Yamato; Simone Lorraine, The Star of the Seine; and Maetel, Galaxy Express 999 Next is the strand of anime that takes it inspiration from the Western literary tradition. They were very popular at the time not only in Japan but also Europe and South America. The major studios treading this path were Toei (we owe so much to them) and Nippon Animation (and its earlier incarnation Zuiyo Eizo). I only skimmed the genre as the protagonists aren't always female and when they are, aren't strictly fighting girls. Nor is there any obvious connection with later anime protagonists, especially since the genre declined and eventually disappeared as the otaku fandom commandeered the industry's attention. I included them as they demonstrate anime's preparedness to seriously embrace the female as protagonist for a family audience. The Toei films such as Hans Christian Andersen's The Little Mermaid (1975) and The Wild Swans (1977) while not disposable weren't able to live up to the promise of their source material. The Nippon / Zuiyo TV series such as Heidi, Girl of the Alps (1974), Anne of Green Gables (1979) and Lucy of the Southern Rainbow (1982) are gems that exceeded my expectations. They are also exceptional in having heroines who, unlike their anime contemporaries, are anything but fantastical. The biggest lesson for me, and in hindsight I should've known this, is that once the magical girl genre had successfully established the female as protagonist, the development of the beautiful fighting girl who will blitz the 80s and 90s can be traced most clearly in the final strand I'm examining - and one I hadn't intended pursuing when I began the project: the splash of crimson in shonen anime, ie the supporting female character to the male fighting protagonist. It makes sense, given that the later ubiquitous heroines are intended for a male audience. Their early appearances weren't always auspicious. The archetype is Françoise Arnoul (aka Cyborg 003) from Cyborg 009 (1966, also 1967, 1968 and 1979), who, despite her blood-red uniform, remains an anaemic character throughout the period. Rather more ahead of her time is Kathy Flint in Animal Treasure Island (1971), who brings magical girl autonomy to a violently masculine, if comic, scenario. Fujiko Mine from Lupin the Third (1971, also 1978 and 1979) is even more breathtakingly liberated until Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahato bowdlerise and contain her. It will be Go Nagai, however, who will form the link between Françoise Arnoul and the more sophisticated female characters in the famous robot shows of the late 70s / early 80s. His sour treatment of his female characters in Mazinger Z (1972), Cutie Honey (1973), Getter Robo (1974) and UFO Robo Grendizer (1975) belies their growing capabilities and depth (though I don't want to overstate either). Space Battleship Yamato (1974) provides the female character, Yuki Mori, who is considered the first otaku darling. More importantly, later heirs to the giant robot genre will provide their audiences with an array of complex female support characters beginning with Yoshiyuki Tomino's Mobile Suit Gundam (1979, the movie trilogy of 1981 reviewed), Space Runaway Ideon (1980) and Aura Battler Dunbine (1983). (I note that Tomino also directed the second half of The Star of the Seine.) The female characters of Super Dimension Fortress Macross (1982) aren't quite as strong as Tomino's, but are memorable nonetheless, while Remy Shimada of GoShogun (1981) combines smarts with a femininity (however undefinable that might be) designed to appeal to a male audience. That combination will become a feature of one strand of beautiful fighting girls over the next decade, including a notable re-imagining of Remy herself. ...girls

Top: Oscar François de Jarjayes, The Rose of Versailles; Sayla Mass, Mobile Suit Gundam; and Chie Takamoto, Chie the Brat Bottom: Remy Shimada, GoShogun; Misa Hayase, The Super Dimension Fortress Macross; and Yuu Morisawa, Magical Angel Creamy Mami Looking at individual anime there have been surprises. On the positive side, there was Princess Knight's unexpected thematic depth, the incongruous adult sensibility that constantly seeped out of Fairy Princess Minky Momo (1982) and being utterly beguiled by the three Masterpiece Theatre shows - Heidi, Girl of the Alps, Anne of Green Gables and Lucy of the Southern Rainbow. And, admittedly no mecha fan, I enjoyed Tomino's three shows in the genre - probably because of his strong and interesting female characters. The revelation, though, is the other Tomino show that I watched, The Star of the Seine, with its French Revolution scenario, a sweet heroine who becomes a deadly fighter for justice, its breaking of new ground for a series geared to a female audience, and its allegorical ruminations on the emancipation of women in postwar Japan. Overshadowed by the later, and superior, Rose of Versailles, and unashamedly inpsired by the latter's source material it is nonetheless a crucial link between the early magical girl shows and later, more violent, action series - in particular, the girls with guns genre. On the negative side, despite how much a debt is owed to Toei through all four strands examined here, both their magical girl shows and the Go Nagai giant robot shows were excruciatingly dull much of the time. That the latter were all too often odious as well, didn't help. Beautiful literature girls