The Spring 2020 Manga Guide

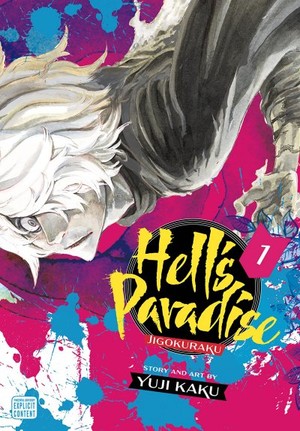

Hell's Paradise: Jigokuraku

What's It About?

Gabimaru, known as “The Hollow,” is a feared ninja assassin, betrayed by his village. They felt he was growing soft and feared that his love for his wife, the chief's idealistic daughter, would induce him to run away, and so they set him up for capture and execution. When he cannot be killed due to his continued investment in life, he and other dangerous criminals are given an ultimatum: go to a mysterious island and find the elixir of immortality. If he can bring it back, he'll receive a full pardon. If he can't however…let's just say that there are things on that island that are worse than mere death.

Gabimaru, known as “The Hollow,” is a feared ninja assassin, betrayed by his village. They felt he was growing soft and feared that his love for his wife, the chief's idealistic daughter, would induce him to run away, and so they set him up for capture and execution. When he cannot be killed due to his continued investment in life, he and other dangerous criminals are given an ultimatum: go to a mysterious island and find the elixir of immortality. If he can bring it back, he'll receive a full pardon. If he can't however…let's just say that there are things on that island that are worse than mere death.Hell’s Paradise: Jigokuraku is written and illustrated by Yūji Kaku. It was published by Viz in March both digitally ($8.99) and in print ($12.99).

Is It Worth Reading?

Rebecca Silverman

Rating:

There are a few elements of Yūji Kaku's Hell’s Paradise: Jigokuraku that definitely feel a little too familiar. Whether that's just because they're pop culture staples (Ninjas! Assassins! Ninja Assassins!) or because they're terms we've seen before in other manga (such as “hollow”) almost doesn't matter; suffice it to say that the book simply doesn't feel entirely fresh. That's far from a non-starter, however – despite its derivative elements, this is an entertaining book, taking those bits and pieces and managing to make them into something that, if not wholly new, is at least a story worth paying attention to.

A lot of this is thanks to our two protagonists, Gabimaru and Sagiri. Gabimaru is a skilled ninja whose training (which is looking a lot like brainwashing by the end of the volume) is coming apart at the seams because of his sweet, optimistic wife. This lands him in hot water with the leader of his village (whose daughter she is, which could have implications later on), and he's set up to be captured and executed by the government. There he meets Sagiri, one of many legendary executioners who use the names “Yamada Asaemon;” she's at the prison to decide if he's a worthy addition to the decidedly shady plot the current shogun is hatching. The two of them are the odd ones in their professions, both having, or having formed, a stronger attachment to leaving people alive than to killing them, and while this has stronger consequences for Gabimaru, there's a definite feeling that Sagiri's gender isn't the only thing making her the target of her fellow Yamadas' distrust. Neither of them are sure which side of the fence they want to be on, either – although Gabimaru knows that his emotional attachment to his wife has made him not want to kill, he's not sure that he wants to live, either, while Sagiri is growing ever more conflicted about whether or not Gabimaru ought to die as well.

Of course, since they've been sent to a mysterious island south of Okinawa in order to find the elixir of immortality for the shogun, the matter of whether or not they live is no longer just up to them. This is another place where the story treads on some too-familiar ground as Gabimaru is just one of many actual cold-hearted and bloodthirsty criminals sent to find the elixir, and for a while it looks as if the cast may be larger than it needs to be. Fortunately for us, Kaku seems to have had that realization too, because the group starts thinning out almost as soon as they're introduced. While this does make parts of the book feel a little disjointed, it also seems like the right approach, because honestly no one else is even remotely as interesting as Gabimaru and Sagiri.

The art does indulge in some pretty graphic violence at times, as might be expected, but that's less of an issue than some random sexual imagery of naked Sagiri being groped by skeletal, blood-drenched hands as she thinks about her profession. There doesn't seem to be much point to this beyond prurience; if Kaku is trying to make a statement about her feeling violated by her work, it's not coming across. But there's more done right than wrong here, and it's an intriguing start to the series. I have an awful feeling that Gabimaru's wife is dead, but even with that potential bit of awful, I'm curious to see where it goes from here.

Faye Hopper

Rating:

I like Hell’s Paradise: Jigokuraku. The character writing, especially for the two mains, is sharp. The first chapter establishes Gabimaru as someone who wants nothing more than to die at the hands of his executioners. This, however, is a mask. Gabimaru, a powerful and feared ninja who has killed hundreds, has been lying to himself about his emptiness, his lack of response to his violent acts. This was a distancing measure, a means to bitterly accept his terrible rut, and a way to deny how happy the love of the one person in his life who saw past his façade—his wife—made him. His co-star, Sagiri (a member of an order of executioners) also struggles to fit into her assigned role. Try as she might, she is terrified of violence. She struggles at cutting cleanly through the neck, giving those she is tasked to kill a peaceful end. She also, like Gabimaru, despises her profession, wishes she could be something, anything else. The way Sagiri and Gabimaru's struggles parallel and allow each other to empathize and grow despite their opposed roles is executed with thoughtfulness and real power, and imbues a gritty, gory seinen with heart.

That said, it is a series that tries very hard to be about the circumstances of its historical era. Sagiri is often talked down to by others, who say an executioner is the role of men exclusively, that women have no place in the field. And the other female characters (like Gabimaru's scarred wife, or several women who are murdered) are archetypes that are very traditional and limiting. While Hell's Paradise is arguably better than a lot of its seinen contemporaries at treating its female characters with respect and dignity, their roles in the story are still limited by the confines of their society in a way that could be read as misogynistic. I think it is trying to be an exploration of how suffocating and terrible this society is for women, but that is fraught territory, especially in stories that are by and, generally about, men. I hope in later volumes we see a greater diversity of female characters who exist outside traditional social molds.

Though I do wonder if manga's death-game-in-hell premise will clash with the series' strengths (character work, brutally reflecting the anxieties of our cast through horror imagery), and if the ensemble of violent killers will get the same, rich characterization as the leads, I came away very impressed by Hell’s Paradise: Jigokuraku. It has terrific, macabre art (I love the eerie and terrifying ways people's true selves are shown in the reflection of Yamada's katana) a solid hook, and richly articulated characters who I am happy to see more of. It's a violent manga that is certainly not for everyone, but it is a series about how casual, uncritical brutality hurts the soul, and that revulsion to it is normal and should be accepted. I can't help but admire that.

discuss this in the forum (56 posts) |

back to The Spring 2020 Manga Guide

Feature homepage / archives