Manga Creation with Kazumi Yamashita

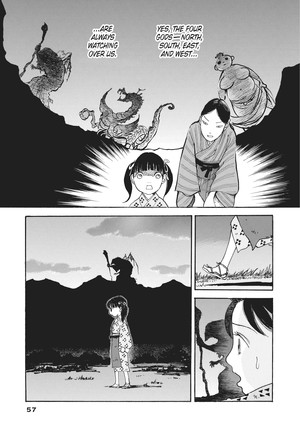

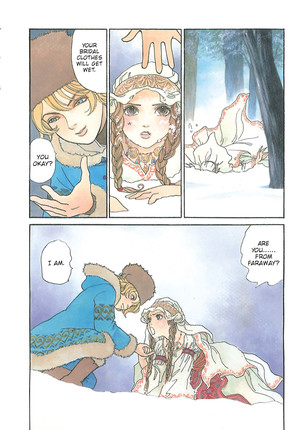

by Rebecca Silverman,Manga creator Kazumi Yamashita has been crafting stories in the medium since 1980. Originally debuting in Margaret, Yamashita has moved fluidly through both shoujo and seinen magazines, bringing readers stories that are steeped in humanity even when they don't deal with characters who are, strictly speaking, human. 2025 marked the first time her works were translated into English, with Yen Press publishing Land followed by Wonder Boy, both stories that skirt the edges between science fiction and fantasy while delving into what makes humans human. We were able to discuss Yamashita's career and works, and if you haven't had the chance to pick up her manga, hopefully her own words will inspire you to do so.

How have you seen the manga industry change over the course of your career? Beyond analogue versus digital tools, what's different now from when you began in 1980? Has the definition of “shoujo manga” or “seinen manga” changed?

You've mentioned being inspired by Mariko Iwadate as a creator. Was it specifically the otomechikku style of storytelling that spoke to you, or was it something about her stories and artwork? How do you think those influences showed in your early works?

YAMASHITA: Although Mariko Iwadete-sensei's work may be simply described as"maiden-like," I think she is a rare example of someone who is able to express the minute emotional fluctuations and cruelty that are unique to girls not through action, but through skillful psychological descriptions and lovely expressions. That's what attracted me to her.

YAMASHITA: Shoujo manga lives in its era (or maybe lives more on a day-to-day basis) and so embodies the feelings of girls who exist in that particular moment. That's why I think it reflects the times very strongly and also why it's so hard to continue to create shoujo manga over a long period of time... The reason I originally applied to a shoujo manga magazine was because I read shoujo manga as a teenager and didn't know much about other manga magazines; plus, my first finished work was over 40 pages long, and at the time, Shueisha's Weekly Margaret was the only magazine accepting submissions with a long page count.

Do you think that blanket demographics like “shoujo” and “shounen” are outdated? Do you ever find yourself blurring lines between demographics and genres?

YAMASHITA: I've never felt that it was outdated. Rather, shoujo manga itself has changed over the years. For example, depending on the magazine, there are shoujo manga that middle and high school girls read excitedly, while there are also shoujo manga that elementary and middle school girls read who want to act a little more grown up. It feels like it has become more specialized. By the way, in the 1960s, a single magazine could contain a wide variety of stories, including coming-of-age stories, stories about mothers and children, school manga, horror stories, stories set in foreign countries, comedy stories, and historical stories. In that sense, the world feels smaller now. At the time, the world of shojo manga was gradually narrowing, and I was beginning to lose track of what to draw. I think that's when magazines for young men became the outlet for me.

YAMASHITA: At first, I didn't even think of it as science fiction. I've never really been a fan of the genre myself. The inspiration for this work came from a geographical misunderstanding I had as a child. I was born in Otaru, Hokkaido, but my parents were from Tokyo and moved there 10 years before I was born due to my father's job transfer. I grew up at the foot of Otaru's ski resort, overlooking the northern sea. When the weather was good, I could see the Mashike mountains far beyond the sea. Until I started elementary school, I believed that was the Soviet Union. This was during the Cold War, which meant there were news reports about the Cuban Missile Crisis and nuclear tests, so I think I had a vague sense of fear in my mind as a child. It felt like a missile might fly over the mountain in the distance. Also, there was a large cemetery on the ridge of the western mountain, but as a child I had never visited my relatives' graves in Tokyo—to me the grave markers looked like the skyscrapers of Manhattan. Maybe that's because I never left Otaru and just stayed at home watching TV. Until I started elementary school, both foreign countries and Otaru seemed like a jumble. If I had stayed there without any ever learning anything, I might still think like that. I think that misunderstanding is reflected in Land. In my opinion,it's easy to deceive people if you so desire, which means to me, it's important to go out and find out the truth for yourself.

Both of your series to get English releases (so far; I'm hoping for more!) examine man's inhumanity to man through different lenses – Land looks at the ways religion can influence how people treat each other while Wonder Boy has elements of a war story. Is this a theme you're drawn to? Does the international scope of Wonder Boy indicate a message to readers?

Your works have been translated into many languages – English, French, and Italian, among others. What unified message do you want to send out to your international audience?

YAMASHITA: This is a message I want to convey to myself—I don't know if what I see before me is real, so it's imperative that I look at it from different perspectives.

Do you have any series that you'd particularly like to bring to international audiences?

YAMASHITA: I hope everyone picks the stories they think they'd enjoy reading.

Do you have a story that you'd like to tell that you haven't yet? Any genre you'd like to create in that hasn't yet happened? Why or why not?

YAMASHITA: Right now I'm writing a fun family story, but my next one might be darker. There's quite a wide range. Regarding Wonder Boy, I'd like to introduce a second main character in addition to the boy and move the story forward. Will the boy be chasing the new protagonist, or will he be chased instead? I feel like we could see a completely new development that's different from what's come before.

YAMASHITA: Thank you for your interest in my work. It's been my dream to have an English version of my manga. And the fact that it can be read from right to left without flipping the picture around was something that wasn't possible in the past. I am truly happy that the world of manga has become an independent language and has spread throughout the world as a common language. I read it and get angry and cry. I hope that everyone can feel something and understand each other. And I hope that one of you will become a manga artist who creates manga that can move the whole world. Even a small emotion is fine. Thank you.

discuss this in the forum |