The Depiction of Hikikomori in Japanese Pop Culture: Can the Anime Industry Help ‘Social Recluses’ Break out of Their Shells?

by Maja Djordjevic,Distorted representations are endemic to pop culture. By definition, the latter upholds the target ‘popular’ narrative and its basic purpose — instant gratification delivered by means of entertainment. When tackling complex concepts, pop culture prevalently concerns itself with fan service.

On the other hand, the consumers' tendency to exotify or barbarize ‘foreign’ cultural aspects and displace them from their original context is commonplace. As a result, pop culture is habitually paying lip service rather than helping the actual cause. Lack of knowledge on the part of the consumer is the usual suspect.

Heed the disclaimer while reading on, for hereby discussed is one such cultural specificity — the hikikomori phenomenon. I implore you to look beyond the implicit uniformity of pop culture. It goes without saying that learning something new about Japanese culture is a welcome side effect. Kindly keep in mind that dissertated below are living, breathing human beings set against the backdrop of psychological diversity — an insurmountable conundrum in its own right.

Defining Hikikomori

The hikikomori lifestyle was first brought to public attention in 1970s Japan and has been well documented. Typically, hikikomori translates to either a “recluse” or a “shut-in” in English, but neither gives justice to the truth.

“Hikikomori” is a compound word coined from the terms hiki (引き, “to pull”) and komoru (籠る, “to hide away,” “to stay inside one's shell”). Thus, hikikomori are “people who withdraw from society” (the singular and plural forms are the same).

Sometimes a more formal term shakaiteki hikikomori (roughly translates to “social recluses”) is used in Japan. Since reclusiveness has many guises and at least as many terms describing them, the shakaiteki variant is preferred. Regardless, I'll stick to the standardized hikikomori for clarity's sake.

Hikikomori Are Not to Be Confused with NEETs

Another form of reclusiveness the anime fandom is customarily familiar with is “NEET” (“Not in Education, Employment, or Training”), a phenomenon commonly defined as “occupational withdrawal.” The terms “hikikomori” and “NEET” are not interchangeable, notwithstanding certain similarities that cannot be excluded.

To clarify: there are established criteria for hikikomori. Back in 2003, the Japanese government released a 141-page set of guidelines detailing behaviors and attitudes defining the hikikomori, which include:

- A stay-at-home lifestyle that lasts beyond six months

- Lack of willingness to attend work or school (except for people who maintain personal relationships)

- Exclusion of established mental disorders with similar symptoms

As regards NEETs, they are not necessarily recluses. As per the governmental definition, these are “people who are not employed, not in school, not a homemaker, and not seeking a job.” Unlike hikikomori, NEETs don't necessarily conform to “not maintaining personal relationships.” It naturally follows that NEETs stand a higher chance of reintegrating into society (should they so desire) or, at the very least, fragments of society they may fit in. The process may be challenging, but it's doable.

For example, ReLIFE's Arata Kaizaki can't be defined as a happy-go-lucky individual who's gone geeky because he's bored. He has real issues he doesn't know how to confront, but once he gets a chance at a new life, he takes it. His ReLIFE mentor Ryō Yoake hopes that Arata will “let his heart, which had dried up and gotten stiff, beat once more.” This definition doesn't befit a hikikomori; a lack of motivation doesn't trigger their state of mind.

Eden of the East's Yutaka Itazu (a.k.a. Pantsu) paints an even more vivid contrast. He is proud of being a NEET (you'll never find a hikikomori proud of their ‘condition’). True to his determination, he is resourceful and a great asset to the team. He is as far from being insecure as humanly possible; his past traumas don't dominate his lifestyle.

While Yutaka's personality is at the other end of the spectrum from Arata's, both can deal with the situation at hand and aid a cause with a little help from their friends. Hikikomori don't have that opportunity — forming a friendship can prove difficult when one doesn't leave their room.

Not Every ‘Social Recluse’ Is a Hikikomori

For two notable reasons, the phenomena's frequent depiction in manga and anime has given rise to a slew of unfortunate misconceptions and misinterpretations abroad.

The first is the apparent confusion when drawing a boundary between the two groups. With so many similarities, who is to say that a hikikomori isn't allowed to enjoy NEET-like bouts of geekiness? This reason isn't detrimental per se, so a failure to draw a strict line isn't necessarily insulting. By contrast, the second reason — conventional neglect of sensitive cultural subtleties — can be perceived as derogatory, ignorant, and arrogant by the hikikomori themselves. It simply cannot be excused by perpetrators' unfamiliarity with Japanese society.

As mentioned above, it's not unusual for a culture-specific term to be interpreted through the respective prism of other cultures attempting to define it. Nevertheless, delicate matters should be treated with care. It cannot be underlined enough that differences between cultures rooted in diametrically opposed philosophies are doomed to be lost in translation. As any ethnologist will tell you, languages are integral to their specific cultures.

For illustrative purposes, consider the fact that also used here is a rather unsuitable terminology such as “phenomenon” (replaced by “lifestyle,” where applicable) and “peculiarity” even though hikikomori don't describe their “condition” as either phenomenal or peculiar.

Similarly, even though the mainstreamization of anime has resulted in the recognition of related phenomena in other cultures, not all people suffering from social withdrawal equal hikikomori. Different cultures uphold different expectations, after all.

Lastly, it must be said that Japanese policymakers have set in place several initiatives in an attempt to reach out to increasingly isolated individuals and groups, with results being nowhere near ideal. That's why the depiction of hikikomori in Japanese pop culture — which ranges from excessively tragic to darkly humorous — should by no means be treated as a spectacle.

Industrialized Society Meets Traditional Values

If you stop to consider it, manga and anime populated by hikikomori characters are usually set in present-day Japan (real or alternate). There's a good reason for it. The Japan of today is an advanced industrialized society. However, the country has a long history of isolationism (look up “Sakoku” and “Jōi Chokumei”), which has resulted in traditional values blending with modern practices. To this day, Japan remains a predominately conformist society.

Individual conduct is expected to live up to high societal expectations rooted in traditional hierarchies (Japanese honorifics should give you a basic notion of the practice). At the same time, the hectic way of industrialized life adds pressure to the mix.

Further out, deeply engraved in the Japanese and other East Asian cultures is Confucianism, a teaching that favors social harmony over individualization (“collectivist values”), a conjecture originally proposed by psychoanalyst Takeo Doi in his 1971 book The Anatomy of Dependence. It shouldn't come as a surprise that, regionally, social withdrawal is not unique to Japan alone. Other East Asian countries face the same challenge (e.g., some 300,000 social recluses have been evidenced in South Korea).

What is specific for Japan, however, is the so-called honne–tatemae divide, where honne (本音) is the concept of true feelings and tatemae (建前) — behavior displayed in public. Tatemae is basically set up to uphold societal harmony, known in Japan as wa (和).

Doi specifically notes that while the two concepts may be aligned in some cases, when they are not, tatemae leads to “outright lying in order to avoid exposing the true inward feelings.”

As if things weren't complicated enough, there's another aspect to consider. Takie Sugiyama Lebra, a seminal anthropologist of Japanese culture, argues that the Japanese social self (as opposed to the inner self) has four “zones”— omote (front), uchi (interior), ura (back), and soto (exterior). An individual shifts from one zone to another to uphold tatemae.

Strict Societal Expectations Are Fueling Seclusion

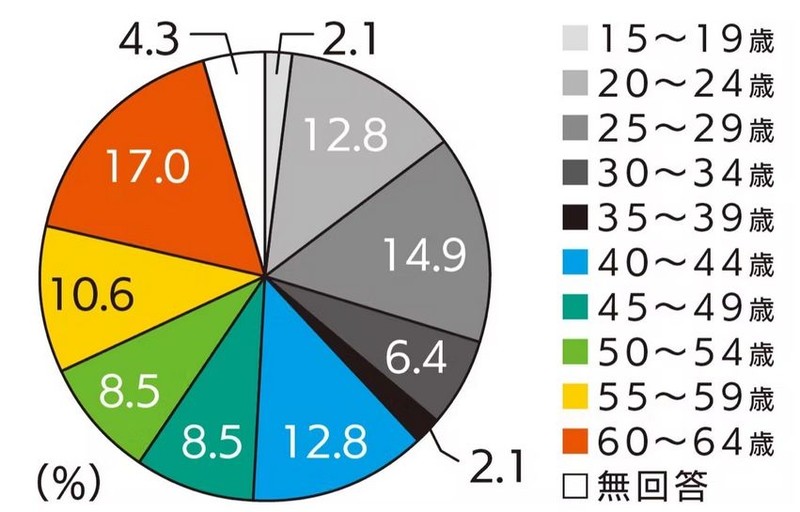

Societal expectations in Japan are multi-layered and difficult to meet, especially for inexperienced individuals. That's why it is usually surmised that most hikikomori are young people terrified of the scary amount of adult-life expectations. While this is often the case, the other side of this problem seems to have flown under the radar.

Consider this: In 2019, The Tokyo Metropolitan Government conducted a “Survey on the Status of Support for Withdrawal, etc.,” which showed that there's a new “middle-aged and older social withdrawal group” consisting of “parents in their 80s supporting the lives of their children in their 50s.”

It's basic math: if the phenomenon was first evidenced in the 1970s, how old are these people today? Some estimates put the number of hikikomori at approximately 1.15 million people (1% of the population). Still, experts warn that the actual number may be considerably higher — around 10 million.

Sometimes, anime touch upon this sensitive topic but never puts it in focus. Using the same series from above as an example, ReLIFE's Takaomi Ōga (Kazuomi Ōga's brother), whose personality abruptly changes due to harassment, turns into a hikikomori.

Takaomi is often described as a shut-in NEET by the fandom, but I beg to differ: his personality perfectly fits the hikikomori definition. ReLIFE offers a possible alternative: Takaomi is given the same chance as Arata. Perhaps, if a prospective friend appears, things may start looking up?

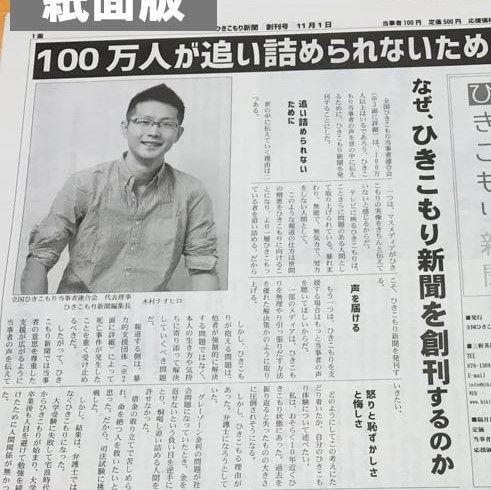

A project deploying the same mental physics has been underway in Japan since 2016, when the first edition of the Hikikomori Shimbun newspaper saw the light of day. The newspaper publishes articles, columns, and interviews by hikikomori and professionals offering a helping hand. Information about counseling is also included, and even self-help groups are being advertised.

Similar initiatives can be found scattered across the wide web. It would seem that hikikomori have, at least, begun communicating among themselves.

An Otherworldly Encounter: Hikikomori Meet the Anime Industry

As aforementioned, hikikomori have been internationalized by the anime industry. I am conflicted about whether the trend contributes to raising awareness of their plight or adds to their troubles.

In Japan, these people are too often seen as spoiled and lazy, but the notion has been contested by psychiatrists, who have pinpointed the mechanisms that trigger the withdrawal process. Hiroshi Sekiguchi, a psychiatrist and the author of Hikikomori to futōkō: Kokoro no ido o horu toki (literal translation: “Social Withdrawal and Refusal to Attend School: Digging a Well in the Mind”) may have coined the most factual explanation: “Hikikomori want to establish ties with society, but do not find it possible to do so. Social withdrawal may be their last-resort strategy for staying alive within this society, and the only option left for them to preserve their own dignity.”

Hopefully, the Hikikomori Shimbun will inspire other publications and virtual meeting spots for these people. It is reasonable to expect that people with similar experiences should be able to connect at some level, just like other psychotherapy group members do.

Meanwhile, the next time you laugh at silly mannerisms or otherworldly musings of your favorite anime's hikikomori, think twice about the real-life consequences of such subconscious actions. Unless you're watching Welcome to the NHK, that is. The series' protagonist and self-proclaimed veteran hikikomori Tatsuhiro Satō is literally asking for it!

This brilliant character actually utters his primary concern: “The biggest problem is that humans are organisms that lie.”

“Spot on,” Takeo Doi-sensei would probably comment.

If you haven't seen this masterpiece, do reconsider. Not your average plot, this one! The NHK anime is brutally blunt to the point of discrediting tatemae, alternating hilarity, dark humor, and depression in such a masterful manner that it keeps the viewer glued to the screen in anticipation.

Inspired by the eponymous book by Tatsuhiko Takimoto, the anime series is a unique rollercoaster of emotions. There's also a manga adaptation illustrated by Kendi Ōiwa (licensed in English by Viz Media), so the choice of format is entirely individual.

Another solid depiction of a not-your-average hikikomori is Jinta Yadomi (“Jintan”). The anime is titled anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day and details the main character's path to social reclusiveness. anohana is a slice-of-life anime tackling profound concepts revolving around six young characters. Similarly to ReLIFE, an outsider gives a boost to the hikikomori, but this time, Jintan has to confront his past trauma with the help of the friends he's fallen out with.

In terms of profundity, anohana cannot hope to rival Welcome to the NHK, but it's a worthy watch all the same.

Lastly, I find it perfectly suitable to conclude this complex topic with one notable supporting character. Bungo Stray Dogs Season 3's Katai Tayama provides an invaluable insight into hikikomori's thought processes.

Scilicet, Tayama describes his existence as “I'm no more than the largest piece of compostable trash in this room.” A typical example of a ridiculed hikikomori, he has resigned from any notion of social reintegration. Imagine how a real-life counterpart of his may be feeling.

Bottom line, we might laugh at Tatsuhiro Satō's relics, empathize with Jintan's tribulations, cheer at Takaomi Ōga's attempts at social reintegration, and be saddened by Katai Tayama's resignation. Still, the sentiments should propel recognition and understanding, not serve as passing entertainment. The percentage of social recluses is on the rise everywhere; the sacrifices of rapid modernization demands are too tragic to be dismissed. How great would it be if we could somehow come up with a viable solution with the help of our favorite pastime?

Maja is an ethnologist and a former English language tutor, adventurer by nature, and writer at heart. Loves scribbling above all else! Dividing her free time between lengthy trips to Middle Earth, Brattahlid, and Bakumatsu Edo, Maja occasionally ventures into the late Anthropocene, where she studies calligraphy and the Japanese language.

discuss this in the forum (17 posts) |