Home Is the Battlefield for the Young 86

by ZeroReq011,When protagonist Paul Baumer returns from the no-man trenches on leave, he finds himself alienated in his childhood home. Men of white, greying hair and smug, portly disposition crowd around Paul, dismissing his frontline soldier assessments, enraptured by cigar-lagered armchair play. Books and sketches of childhood interest offer Paul no more fancy or warmth—their meanings just the literal observation of dried black ink on dead plant matter, their sensations the chill of the eve Paul revisited them. What was to be respite from the stress of battle became a new and unfamiliar stress the twenty-something-year-old Paul could barely handle, and he departs his former hometown, regretful about ever returning. No longer the person that place once knew, Paul's true and actual home is now very different: on the battlefield, with his comrades. And one-by-one, they all die there.

It is from this scene and the larger story of Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front that 86 -Eighty Six- draws its brutal and unglamorized characterization of war and the toll it takes on the young people that are drawn into fighting it. Like Paul, Shinei “Shin” Nouzen and his 86er comrades are given leave from the fighting. Unlike Paul, Shin and the 86 are offered the opportunity to retire from it all. And yet, after a hard-fought escape, a miraculous rescue, and a bout of rest (perhaps too much rest) they all decide, to their saviors' bewilderment, to return back. They feel they must.

A War for the Soul of Humanity

The Federal Republic of Giad's (henceforth the Federacy) perplexity comes from two places: the 86's tragic circumstances and their own idealistic values.

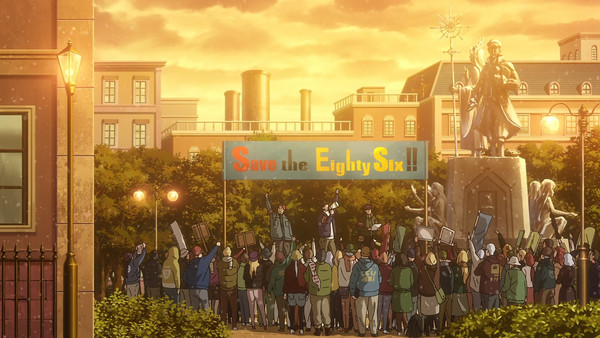

The 86 were a people impressed by their home country to fight to extinction, so why would they want to go back to doing anything remotely comparable? More about it can be read about in this previous article, but to briefly summarize, an ethnonationalist regime took over Shin's country, the Republic of San Magnolia (henceforth the Republic). Around the same time, war broke out between the Republic and its neighbor, the autocratic Empire of Giad (henceforth the Empire). Exploiting ethnic tensions that already existed and opportunities that war panic provided, the supremacist Alba majority government disenfranchised the Republic's minority ethnic groups, re-labeling them all “86”, after the name of the ghetto they were concentrated in. Dehumanizing them to a number while arguing “better us than them,” Alba supremacists forced the 86 to fight the war in their stead while purposefully supplying them with inadequate arms, with the intent on having no one survive. This program of effective genocide wiped the 86 out to their last, youngest, underaged generation, who managed to just barely cling onto life by becoming the hardiest of hardened soldiers. Even these battle elite 86 soldiers hold no value to the Alba government, for even the fittest of them are designated to die in a final suicide mission that all but assured their doomed fate.

That Shin and his comrades survived all this would be seen as a miracle and a mercy. And yet, they seem determined to forsake the forces behind both and put themselves deliberately in harm's way by taking up arms yet again. Are they doing this out of thanks to the Federacy, the country that rescued them? But the idealists in the Federacy's political and military structure would be loath to take advantage of any gratitude or guilt the 86 might show. A mighty influential (though not all-powerful) Federacy figure, President Ernest Zimmerman, goes so far as to declare any country that would manipulate child refugees into fighting its battles deserves annihilation, even his own.

The relatively new Federacy arose from the ashes of the Empire through revolution; it would therefore be against the values of many Federacy leaders and denizens to impose a remotely comparable oppression on the 86. Reacting to the Empire's tyrannical policies, the Federacy strives with zeal to be everything the Empire was against, which also makes them a narrative foil to the Republic. The Republic claims to be an egalitarian society despite segregating and purging itself of ethnic undesirables. The Federacy takes its ethnic diversity as a point of pride and a reason for its revolution against privileged classes organized by ethnicity. The Republic claims that it doesn't force people to fight its wars by deviously pushing the fighting onto imaginary advanced autonomous drones and then minorities that it doesn't consider people. The Federacy has rejected both autonomous fighter and mandatory drafting programs—its military ranks are replete with people who have all willfully volunteered to fight the war and risk their lives despite having the option not to. The now-ruined Empire had turned to intelligent military machines it thought it could control to fight their wars. The surviving states now fight just the one war against machines out-of-control, a war whose loss would mean humanity's annihilation.

The Federacy and other states formed alliances with each other after reconfirming their survival, setting aside their differences to fight the Legion together as fellow human beings. The Republic compromised the definition of what is considered human, hoping to ride out the machines' rampage behind walls separating them from the 86 and everyone else. Ernest and many in the Federacy take their country's values seriously. They consider the 86 a people so battered by humanity's worst impulses that they deserve a pass from any obligation to its salvation. Shin and his 86 comrades turn that mercy down though, and to their great confusion, decide to return to the frontlines.

The 86 aren't overly concerned about returning favors or repaying debts. They don't desire pity or permanent relief. They simply aren't comfortable with everyone else's idea of peace and normalcy. They can't imagine it well, because after all, they've been soldiers most of their lives. All they know, and know best, is the battlefield.

A War About Nothing Especially Personal

That feeling of unease with peace, common among war vets, is one that especially affects young people like Shin and Paul. Like Shin is in a way to 86, All Quiet on the Western Front is the story of Paul, a fictional character based on the experiences of young soldiers who experienced the horrors of modern warfare, namely World War I (WWI). History has long been replete with stories of skilled warriors who triumphed gloriously or sacrificed heroically in battle, though the extent to which most people back then thought of war in such glowing terms is up-for-debate. That positive-seeming attitude toward war, however, took an unambiguous turn for the worse sometime after the development of efficient, high casualty weapons. The Western Imperial powers of pre-WWI Europe did utilize this weapon against outgunned natives in their colonies, and did observe its use on their peripheries in the American Civil and Russo-Japanese Wars. Unfortunately, they never fully appreciated what a game-changer the machine gun was to warfare until they unleashed it on each other on the mother continent.

Europe had been enjoying so much peace and prosperity up until WWI due to technological advances and colonial wealth that it started getting boring for some, and people were warming up to the idea of some warring to shake things up. Austria-Hungarian archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by Serbian anarchists, anarchists the Austria-Hungarian Empire believed were tied to Serbia. Hungry for war retribution and concessions, Austria-Hungary issued an ultimatum to Serbia containing deliberately unacceptable demands. In response, the rival military alliances the Austro-Hungarians and Serbians were members of—alliances every major European power was also a part of at the time—activated and mobilized. With neither camp wishing to see one gain over the other, the whole of Europe was dragged into war, all on the bases of localized conflicts and great power maneuvering that had little to do with the personal lives of most Europeans. And yet, leaders exhorted their peoples to fight.

European leaders believed that the war would be short and disruption would be minimal, something they would be sorely mistaken on as the machine gun made the old tactics Europe used for warfare horribly obsolete and costly. Everyone had access to at least some of the latest firearms. Everyone had machine guns. The quixotic image of soldiers marching boldly and progressively through the battlefield was cut to ribbons with repeated hails of machine-gun bullets, replaced with the picture of soldiers digging trenches that could provide some semblance of cover for riflemen and machine-gun nests. This defensive tactic of trench emplacements, while less costly if everyone just stayed in their holes, achieved no bold and very little progress. For years, politicians and military planners banged their heads searching for decisive answers to the hasty solution-turned-hard-stalemate of trench warfare, wasting the lives of soldiers, professionals, volunteers, and conscripts in the process—an ebb and flow of attacks and counterattacks pre-empted by large artillery fire, met by machine-gun fire, joined by late tank and aerial fire, and bookmarked by chemical gas.

The war took many lives and scarred countless others—a whole lost generation of young survivors resembling Paul, whose most important life experiences up to that point in their young lives were a conflict that was objectively brutal, strategically frustrating, and fundamentally meaningless. After undergoing so much trauma with nothing really gained and no good enough reason for being fought, many young vets retiring back into civilian life faced harsh cultural shocks. For war youth like Paul, interests in topics that normal people found motivation in seem frivolous or off-putting now in the face of life's frailty and altered perspectives. Topics that normal people make light of and assume too much about come off now as more irritating if not downright insulting. The cacophonous sounds of city streets might be confused every now and then with rifle fire and artillery discharges, and the cracks in concrete and rusting of iron that were always there but unnoticed until now might be the only things left that they can find appreciation in. Paul couldn't understand the normalcy of his hometown anymore, nor could it really understand him, so he pushed it away and left it for what he understood best.

This place, this home, that Paul and Shin now know best is the battlefield: the locus on which their worldviews revolve around, in a paradox of comfort and fear—like an abusive partner. It is a landscape where they find like-minded comrades in and take some pride surviving and being hardened by, and yet it is also something that destroys and deprives: taking the lives of foes, rending the lives of friends, fully capitulating one's own. It is their home, but it's not a good one. Paul becomes so distraught in the field after the death of every close comrade he had that he ends up abandoning all sense of situational awareness, eventually losing his life to a sudden bullet while standing dazed in a trench. Shin grows increasingly unconcerned with his own survival, having put down one comrade from the Federacy that wasn't scared about approaching him, having learned about the possible loss of another cherished comrade in the Republic, and reminded through it all how so many people who have gotten close to him end up going away and leaving him alone. Through the monitor sensors of Federacy soldiers who witness Shin and the other 86 fight with reckless abandon, and the special eyes of Frederica, who herself is terrified at what Shin might become when he stops caring, we see Shin following in the footsteps of Paul—to an early grave.

A War Deciding Their Futures

Paul and Shin's situations aren't identical though, and the wars they end up fighting aren't exactly the same. One tragedy of Paul's in All Quiet on the Western Front is no one understanding or really helping out the traumatized young man, no support network besides his comrades (who all died anyway) to empathize with him and push back on his self-destructive thoughts. His mother makes an honorable attempt when he comes back on leave, but she's too old and sickly, and lacks the energy to properly console and confront him.

On the other hand, Shin has people who want to understand his pain and share their visions for a better life outside the war and after it. However, two of those people are beyond Shin's reach now. His surviving 86 comrades don't help and even abet in Shin's self-destructive proclivities, because how could they not? Like Shin, they too are quite uncomfortable with imagining a life of peace, let alone enjoying it, having been raised and taught from youth on to believe that their situation in the Republic, screwed up as it is, is their normal.

More than that, they take pride in such an existence, dancing on the edge of oblivion, fighting and surviving despite the stacked odds. They're good at it; they wouldn't be alive if they weren't. In their minds, that's their most distinguishing characteristic: being fearsome, not pathetic. So Shin and the 86 give everyone pitying them the cold shoulder, from Lena at first to many in the Federacy now. Unable or unwilling to understand where the 8's spurning of their kindness is coming from, many in the Federacy's rank-and-file respond with coldness: disgusting, war-obsessed, monstrous 86. As far as some military planners in the Federacy are concerned, they may as well take up the 86 on their offer, even if it is at the spearhead of another seeming suicide mission.

Not everyone has stopped trying to reach the 86 beyond their self-determined fatalism, however. Lena continued to reach out to the 86 even after that initial coldness. She was instrumental to Shin and the others surviving their first suicide mission, and was the first to ask them what they'd like to do after the war—a war that until now they were sure they'd never see the end of. Ernst too challenges them in similar fashion, hesitantly giving them leave to fight after being initially against it, on the condition that they enroll in the military's officer education program which will give them more options when the war is over. Most obstinate and supportive of all right now is Frederica, who is tearfully upfront about her fears of Shin ending up in a similarly cursed way to a vassal that resembles him so much. Frederica's vassal wasn't so lucky, and neither was Paul. But in one crucial respect, Shin is. From Lena to Frederica, he has people that have never given up on wanting him to leave the battlefield his mind is mired in, pleading with him to come back from the war and call somewhere else home one day.

That's not to say that the war in 86 is something that can be easily given up by everyone. The way the 86 previously fought it in the Republic was cruel and pointless, but there's a good reason why the Federacy and others continue to fight on. Unlike much of WWI, where most peoples weren't fighting to resist their destruction, losing the war would actually mean humanity's extermination. There would be no good post-war reality if the machines win. But right now, Shin is not fighting for the future. He's fighting towards its denial. He's fighting to nihilistic oblivion. He's killing himself faster this way, following Paul to an early grave. But 86 thinks young people like Shin and Paul deserve better. 86 can't change Paul's tragic fate, since 86 isn't Paul's story. It's Shin's, and by surrounding him with people who continue to care and hope despite everything, 86 is trying to prove that Shin isn't doomed to follow Paul.

Social Scientist & History Buff. Dabbles in Creative Writing & Anime Criticism. Consider following him at @zeroreq011

discuss this in the forum (32 posts) |