Sanda Shows that Adolescence is Supposed to be Awkward

by Lucas DeRuyter,

Content Warning: Discussions of Body Dysmorphia

Animated by the acclaimed studio Science SARU and an adaptation of a manga penned by famed BEASTARS creator Paru Itagaki, SANDA was always destined to draw attention. The SANDA anime and manga turn heads while exploring some of the most uncomfortable truths about being a young person on the verge of adulthood at a time when these topics are dominating public discourse.

It's easy to frame an overtly progressive and ostentatious work like SANDA as simply being pro-LGBTQIA or anti-establishment. While these politics are definitely a part of what makes SANDA an affecting and effective anime, the show is more of an exploration of identity and how young people grow into themselves through the awkwardness and pain of youth. This core theme shouldn't be a surprise coming from Itagaki, considering BEASTARS' status as a wonderfully messy exploration of disenfranchisement and the internalization of socially generated guilt. However, SANDA's core themes and politics around young people needing autonomy to become adults and what being an adult means in a healthy society hit at a time when they're painfully relevant.

Some of the most fraught social discourse today surrounds young people and how much freedom they should have in shaping their own identity. Conservative political actors across the globe have turned limiting the bodily autonomy of children into campaign tentpoles in the past few election cycles. Similarly, conservative activist groups have used “protect the children” arguments to pressure digital commerce platforms into removing legal adult content from their storefronts. SANDA also arrives at a time when the exceedingly wealthy have become even more fixated on the idea of youth, both in the sense of preserving their own and exploiting young people in vulnerable positions.

While connecting an anime where a young man transforms into a buff version of Santa Claus to real-world social politics might seem outlandish at first, the setting of SANDA invites a wealth of comparisons to our world today and how it treats young people. The backdrop of this story is a near-future Japan where declining birthrates have functionally made children a protected social caste. As such, this society bends over backwards to provide children with a “trauma-free curriculum” as the main characters' school professes, and the adults in this society fetishize youth to an even greater degree than we do in the real world.

This interpretation of our current culture is best exemplified in the antagonist of the first season of the anime, as well as a frequent oppositional force in much of the manga, Principal Oshibu. This 92-year-old man has undergone countless elective surgeries to make himself appear younger, even going as far as to replace organs like his heart and his eyeballs, all so that he can project the veneer of youthful vigor and competence. The man hates the idea of aging so much that disfiguring scars from his many surgeries will blossom across his face if his age is ever called into question. Through Oshibu, we get constant, graphic reminders of how this fixation on young people can twist someone into an uncanny facsimile of a person, which feels especially topical as gender-affirming cosmetic surgeries meant to evoke unattainable beauty standards for women become more common among the wealthy conservative social class.

The social institutions the titular SANDA and his classmates find themselves in are also designed to give adults excessive control over their lives. The boots that are a mandatory part of their school uniform are likened to prison shackles, meant to keep them from both trying to leave the school and make them more docile through limited mobility. This institution also restricts and censors the education these students receive. Through the physically imposing and typically confident Shiori Fuyumura, we learn that this society heavily limits children's exposure to even artistic depictions of nudity and perpetuates rumors like “kissing causes cavities” to discourage young people from exploring their sexuality.

Oh, and apparently, kids in SANDA are given vitamin regimens so that they don't have to sleep, and thereby delay the release of growth hormones to stay young longer, which in some circumstances can endanger the life of a child.

Collectively, this setting comes across as an even more dystopian version of the puritanical world in SHIMONETA: A Boring World Where the Concept of Dirty Jokes Doesn’t Exist, and is one that is deeply informed by conservative contradictions around youth and young people. This is a world where child rearing and protection are of principal importance, but also one where children are deeply infantilized. SANDA's world prioritizes the idea of giving young people a childhood free of hardship more than giving children the information and experiences needed for them to be well-adjusted adults. Considering how poorly adjusted most of the adults in this story are, SANDA feels both like a cautionary tale and an only slightly elevated encapsulation of conservative attitudes around child raising.

SANDA's thesis of giving young people the freedom to explore themselves and the world to grow from these often stressful processes is further reinforced in SANDA's main characters, who constantly prove that, for the kids to be all right, they need to be a little messed up.

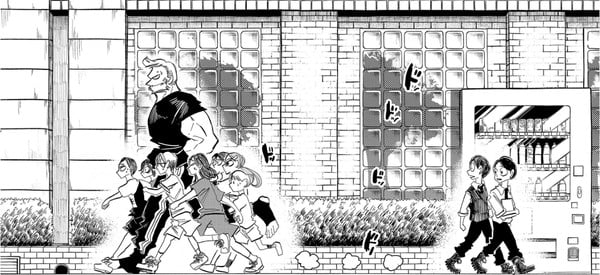

SANDA's leading characters endure dramatized versions of the kinds of trauma and internal conflicts that are hallmarks of adolescence. SANDA's main struggle throughout the franchise centers on his uncertainty over accepting his status as an adult and the obligations to other people that come with it. With adulthood, especially an adulthood informed by a variety of magical abilities based on the Santa mythos, comes power and associated responsibilities. Throughout the manga, SANDA struggles with internalizing his newfound capabilities into his identity and weighing how much he should do for other people against how he can best carry out those acts. This struggle at the core of SANDA's character presents itself most prominently while gathering up and training with other descendants of mythical figures. Here SANDA has to navigate soft skills that many adults struggle with, such as leadership, relying on other people, and recovering from abject failure. The growth through trial and error in transcending adolescence is even literalized in his Santa powers, where he can recover from most injuries so long as other people believe in him and act as his support network.

Fuyumura's adolescent experiences are much more personal and uncomfortable. While she's the most mature character by most markers at the start of the show, it's quickly revealed that she's sexually stunted and has body dysmorphia to the point of questioning her gender identity. SANDA is incredibly sympathetic to Fuyumura's struggles here, and knowledgeable about what it feels like to be a young person enduring this identity crisis. In particular, Fuyumura's father cares deeply about her, but having no idea how to support her in these issues, or even acknowledge them, will ring true for many queer people who have struggled to maintain a familial relationship after coming out to a family member. It's also deeply uplifting that, as Fuyumura navigates these uncertain elements of her identity, her peers maintain nothing but admiration for her and do their best to understand and support her.

This is especially true of Ichie Ono, who has a crush on Fuyumura and maintains her fondness for her friend even as Fuyumura is unable to meet her best friend's budding interest in sex. Ono is an especially tragic character as, after her rapid puberty isolates her from her peers, she dies of complications from her sudden physical developments. As this atypical aging process is the direct result of the society she lives in trying to control her development, the only way to interpret this event is that this stifling society literally killed her.

Other characters in SANDA have their own specific struggles with different forms of maturation, but it's clear from just these three that the anime and manga firmly believe that adolescent hardship is necessary in becoming a healthy adult. SANDA and Fuyumura both become more complete people thanks to the traumas they endure, while Ono dies explicitly because this society does not allow her to explore the more uncomfortable elements of her identity as it relates to sexuality and sexual desire. SANDA's characters and story are a celebration of awkward parts of development that are generally uncomfortable to talk about, but deeply necessary to becoming a full-fledged person.

The conflict in SANDA is derived from these struggling forces: a society informed by global culture's growing efforts to rigidly define youth and control young people, and young people fighting to have the difficult experiences that make young adulthood so special. SANDA boldly and repeatedly asserts that the weird parts of being a young person, like figuring out relationships, attraction, and identity, are actually beautiful and necessary. In SANDA, the consequences of denying young people these semi-traumatic experiences are lethal, and with every new storyline drives home how important it is to give young people the autonomy necessary to make the mistakes that help them find themselves.

Throughout this story SANDA and his friends form a real community, learn how to rely on and support other people, and stand up to the institutions failing them while recognizing that their oppressors are often products of this system. The Descedents Club proves to SANDA that other people in the world can relate to even his most specific and isolating experiences. Fuyumura and SANDA's trial-by-fire relationship rapidly becomes the most meaningful relationship in either person's life, and the kind of relationship that will forever influence the other. Not to mention that, in their repeated conflicts with Oshibu and Fuyumura's father, SANDA's protagonists gain a thorough understanding of how this society and the mentalities that inform it can warp a person into someone who can't even healthily show affection.

SANDA is exactly the story the world needs right now about how hardship, adversity, and new experiences transform kids into healthy adults. Paru Itagaki clearly remembers what it was like to be a young person and knows that idyllic childhoods aren't real. To draw upon my own experiences, I wouldn't trade my childhood and teenage years for anyone else's, but I still had to learn some pretty hard lessons. As a teen, I had to make peace with the fact that many of the people I looked up to as a child were flawed individuals, with several extended family members being alcoholics with little capacity for recovery. I also had to make peace with the fact that, while the community I grew up in deeply informs who I am today, my hometown is actively hostile to my identity and the current life I'm trying to live. Not to mention all of my uncomfortable and poorly informed sexual experiences that were deeply embarrassing, but also necessary stepping stones in figuring out who I am and what I'm into.

While SANDA is a deeply validating show for many with marginalized identities, it principally is an examination of how young people become adults by first failing at adulthood. At a time when the concepts of youth and young people feel more politicized than ever before, delving into the more uncomfortable parts of childhood is growingly necessary, and I hope SANDA inspires other creators to do the same. Though it may be a while before anyone else can strike this perfect balance of absurd and emotional resonance.

discuss this in the forum (2 posts) |