The Evolution of Shōjo Manga in the 1970s with Curator Rei Yoshimura

by Andrew Osmond,

A specialist in manga studies, Yoshimura has curated exhibitions on subjects ranging from CLAMP to Hideaki Anno. Her current project is a forthcoming exhibition in Tokyo focusing on three iconic shōjo manga artists of the 1970s. "Shojo Manga Infinity: Moto Hagio, Ryoko Yamagishi, and Waki Yamato" will run at the NACT from October 28, 2026 until February 8, 2027.

I interviewed Yohimura during her visit to London, focusing on the evolution of shōjo manga in the 1970s.

If you compared shōjo manga at the start of the 1970s and then at the end of the 1970s, what would you say were the most important developments in the market in that time?

Rei Yoshimura: The manga artists that I introduced yesterday [referring to Moto Hagio, Ryōko Yamagishi, and Waki Yamato], they all debuted at the end of the 1960s, and there are a huge number of manga artists who debuted around the same time. That generation of manga artists gained a bigger mass audience. By the end of the 1970s, about a decade after they debuted, they already gained quite a mainstream audience, which expanded the market.

There's also a different kind of transformation. During the 1970s, most of the shōjo manga artists were male, but from the generation I just spoke of, by the 1980s, they were primarily female.

The manga from the 1970s and 1980s deal with very serious subject matter, but they're drawn in a highly stylized way that emphasizes the beauty of the characters and backgrounds.

Yoshimura: Actually, the type of shōjo manga that became popular in the West is just one part of the shōjo manga world. There are some shōjo manga that are a lot lighter and are popular only in Japan. Those manga usually have some contextual backgrounds that only Japanese people would relate to, so that's why they're not as mainstream here.

The real value of shōjo manga in the 1970s was the diversity of topics discussed. In Japan, it was just a lot more diverse than what was popular [in the West].

That connects to my next question. In English-language histories of shōjo manga, some titles are often highlighted, including Rose of Versailles, They Were Eleven!, and The Poem of Wind and Trees (Kaze to Ki no Uta). But which other manga from this time do you think are overlooked, especially in America and Britain?

Rei Yoshimura: Glass Mask is actually as popular as Rose of Versailles in Japan, a very long series. There are also titles from the coming exhibition, like Emperor of the Land of the Rising Sun (Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi by Ryōko Yamagishi) and Hikara-San: Here Comes Miss Modern (Haikara-san ga Tooru by Waki Yamato).

[Regarding Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi] It deals a lot with Japanese history, which is why there's that contextual background, that's kind of missing internationally. Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi was a symbolic work during that time; it had a significant impact on a certain generation.

If you had to guess, what proportion of Japanese readers of the shōjo market in the 1970s were male readers?

Yoshimura: If I really had to guess, it would be 20 to 30 percent.

Some shōjo manga in the 1970s popularized BL themes in manga form. Did Japanese newspapers and mainstream commentators in Japan notice them and react?

Yoshimura: In the 1970s, the BL genre wasn't actually a “thing” yet. It was just one of the themes that were depicted in the shōjo manga at the time, and that was very natural. And nobody thought to put [shōjo manga] in a box, because the diversity was just huge during that time.

Today, it seems that shōjo manga gets adapted into anime far less often than shonen manga. Were shōjo manga adapted more in the 1970s?

Yoshimura: Even in the '70s, there weren't a lot of anime renditions of shōjo manga. First, I think that shonen manga, the themes that they explore, are much easier to turn into anime. Anime require a shorter span of screen time per episode. I think the topics that shōjo manga covers are a lot more like literature or feature films, so it's harder to develop cliffhangers for each [anime] episode than it is for shonen manga. Shonen manga usually get featured in magazines, and each time they get featured, it's around like 16 to 20 pages, whereas for shōjo manga, it's like 32 or 40 pages, so it's much longer. It's harder to cut them shorter.

Yoshimura: Before the war, there were a lot more expectations about gender roles, especially for women. After the war, it started to change, but I think that at first, shōjo manga focused more on themes regarding grief or harder topics. And then it got lighter as the years went by.

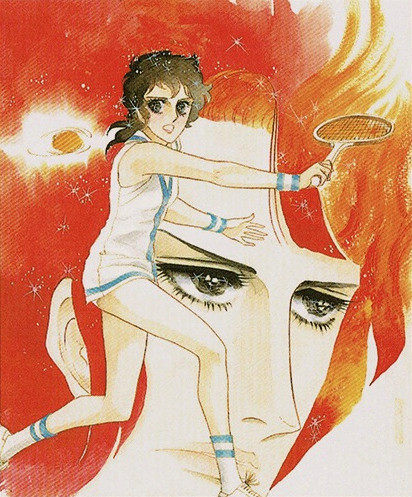

It could be considered that during the 1960s, many more romance shōjo manga came out, which gave women more autonomy in their characterization, which could have contributed to breaking out of expectations. Also in the 1960s, it was extremely popular for shonen manga to have sports themes, so that might also have had some influence.

One very important factor is the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. It can be said that sports in general became popularized through new media such as TV, which aired them nationwide.

Wasn't there a famous women's volleyball team in the Olympics?

Yoshimura: Yes, the Witches of the East [aka Witches of the Orient].)

Moto Hagio has had more of her works translated into English than other shōjo manga artists of the 1970s. What do you think is so universal about her work?

Yoshimura: She is the top artist in Japan, too, so it's quite natural. Her style is very literature-coded. And a lot of her themes are very universal because they feature things like science fiction; a lot of her themes are more relatable to universal audiences. In my personal opinion, even when she writes about contemporary Japan, there's something foreign or universal about her work.

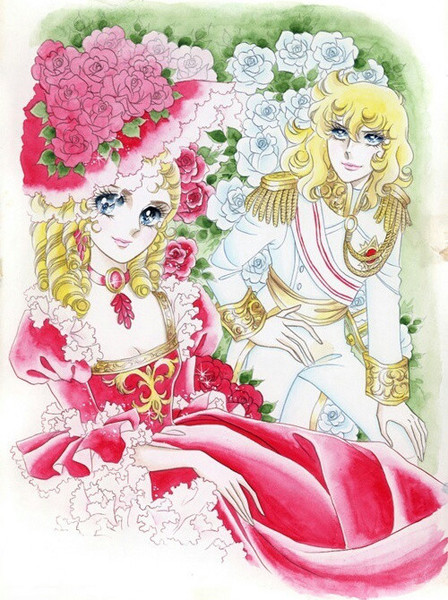

Rose of Versailles is much better known than most of the other works by the artist Riyoko Ikeda. Why do you think it's so much more famous than her other work?

Yoshimura: It's the same in Japan, that Rose of Versailles is significantly more popular. Generally, Japanese people love France; it was especially admired by young women in the 1970s. You learn a lot about French history in [Japanese] school, so a lot of Japanese people are already aware of the history of France. The tragedy of Marie Antoinette is very deep in their hearts, so it comes very naturally for Japanese women.

BL themes still have a big influence on shōjo manga. But I wonder if there are other ways in which you think shōjo manga in the 1970s influence shōjo manga today?

Yoshimura: As I said before, in the 1970s, manga weren't really viewed based on genre, but now they're categorized more than before. One thing that I can think of is ladies' [josei] manga, which is a little bit like a more mature version of shōjo manga, which is popular now. [Yoshimura refers to the "Harlequin" romance novels, originally founded in Canada, which have both influenced and been officially adapted as manga for decades; many of these manga are available in English. See Rebecca Silverman's in-depth article on the subject..] That whole [manga] genre surrounding that theme originates from shōjo manga; I think the readers of shōjo manga popularize it in Japan.

discuss this in the forum (1 post) |