What's So Bad About a Little Change?— A Look at Anime Adaptations

by Jairus Taylor,

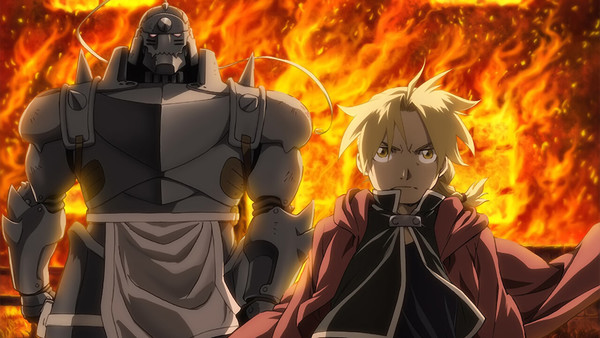

Around the time I was first seriously getting into anime and manga, the most popular anime was the 2003 version of Fullmetal Alchemist. While I was vaguely aware that it diverged from Hiromu Arakawa's original manga and saw that there were fans who were unhappy with the direction that anime took, there were also a lot of fans who outright preferred the anime because of those differences, with both perspectives being fairly common among online fandom at the time. When I eventually got around to the 2003 anime myself, I had already read a fair amount of the manga but was still impressed by the story it presented. When I returned to the 2003 version several years later for Funimation's anniversary Blu-ray release, I found it held up incredibly well and easily stands as one of the best anime of its era. Today, however, its positive reputation within anime fandom has diminished pretty significantly. A lot of this is due to its current lack of availability on most streaming platforms, as Aniplex has been content to spend the last decade or so sitting on it despite its previous success, but an even bigger reason is that it is now perceived as the inferior version of the anime for being a “less faithful” adaptation in the wake of Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood which has since become better regarded for adapting the story of the manga more directly. While that seems to be a pretty open and shut case on paper, it begs the question: just what exactly makes for a good or faithful anime adaptation, and how does that translate into a good anime?

To answer that, it's probably a good idea to start by discussing what's even thought of when we think about what qualifies as a “good” anime adaptation. If you were to ask most anime fans this question, the answer would likely be something along the lines of a largely 1:1 recreation of its source material with some nice animation, and honestly, it's not hard to understand why.

First and foremost, however, it's important to acknowledge that no adaptation can ever really be a perfect recreation of its source material, nor should they ever really be expected to be. Part of this boils down to the obvious, but often-overlooked reality that anime and manga are their own media with their own strengths and weaknesses that can't be easily ported from one to the other. Even the most panel-to-panel adaptation of a manga can't really hope to replicate how panel layouts can be used to portray action, or how shading and line work can be used to invoke specific emotional reactions in the reader, so there's always going to be something that's lost or comes off differently between mediums. The other part of this is that the staff working on any given project are just as much creatives as the original author, and, as such, their sensibilities will always influence how a work is ported from manga to anime. Whether it be in how certain scenes are directed and animated, or what kind of music is used to set the mood for them, how these decisions are executed will pretty much always adapt to feel different, and even the best ones can never be a complete substitute for the original work.

Take the critically acclaimed Frieren: Beyond Journey's End for example. While both the anime and manga are effective at quietly carving out chunks of time in the lives of Frieren and her companions, there are still differences in how that's conveyed between mediums. Though the manga tends to do this through brief panels of their activities that invite the reader to linger on these moments, the anime achieves this through careful visual direction and character animation, that help to sell the illusion of seeing weeks or months pass by in just a few seconds (something which is made even more effective through the strength of Evan Call's orchestral musical score). Under the same notion, while I highlighted its sweeping magic battles one of the anime's biggest strengths, part of what makes the anime's battles stand out so well, is that the manga is comparatively bad at depicting battles through its art, as its action panels tend to very rigid, while the spells being showcased rarely ever consist of anything more than magic laser beams, which all tends to make its attempts at action look dull. Even if these are differences largely in the anime's favor, they are still differences, and ultimately make for two distinct experiences depending on which version of the story you're looking at.

Under that same token, it's also possible for an adaptation to feel almost completely different from its source material, even if it's more or less following the same beats as the manga. One such adaptation would be the first season of The Promised Neverland which is a largely straightforward retelling of the manga's Grace Field arc with the most immediately notable differences being that it trades the in storybook fantasy aesthetic of the manga's art for photorealism, and attempts to further build on the sense of mystery and suspense present throughout the arc by removing any internal character monologues to make it more difficult to parse their intentions. While these changes seem relatively minor compared to changing the overall plot, and the resulting show made for a good season of television, they did have their costs: the emphasis on realism made it difficult for the anime to transition into the more fantastical parts of the manga, which are gradually introduced over time. More significantly, though, removing internal thoughts meant that any character motivations clearly spelled out in the manga were either made more vague or slightly altered to fit this style of storytelling. All of this ends up bleeding into the ways the arc uses its central cast to explore the politics of living under a system designed to rob young people of their futures while pitting them against each other to maintain its status quo, and while these ideas are still there in the anime, they're conveyed less blatantly than in the manga, which is much more overt about what it wants to say. As such, while it's not necessarily a bad adaptation and is still a good show by its own merits, it also doesn't quite capture all of what made the original manga so effective.

To an extent, this is also somewhat true of Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood. While it's certainly truer to the text than the 2003 anime, it falls short when compared directly to Arakawa's manga. In an effort to avoid retreading too much of what the 2003 anime covered, it speeds through the early parts of the manga that had been previously adapted, and while what's shown in Brotherhood's version of these events do mostly hold up on their own, key story beats like Ed and Al's backstory, or the fate of Nina Tucker and her dog are less effective since the faster pacing means that it can't linger on them the same way the manga or the 2003 did. This swift pacing also negatively affects the rest of Brotherhood, as cramming a 27-volume manga into 65 episodes means it sometimes speeds over or glosses over character introductions and parts of the story that aren't immediately relevant to the main plot. Those issues are at their worst during the extended flashback detailing the War in Ishval, which is where Arakawa most directly tackles the manga's themes regarding the aggressive nature of military fascism and the extermination of ethnic minorities. While the manga dedicates an entire volume to exploring the toll this conflict took on both its victims and several of the characters within the main cast who helped perpetrate it, Brotherhood is only able to spare a single episode on it, which gives this part of the story significantly less of an impact, and makes Brotherhood's attempts to tackle those subjects feel slightly more shallow than what was present in the manga. This all isn't to say that Brotherhood isn't a solid adaptation overall or a great TV show in its own right, but it's not without its flaws as adaptation and a lot of what makes it an excellent show is sometimes despite how Yasuhiro Irie and his team at BONES chose to re-adapt the Fullmetal Alchemist manga as much as it is because of it.

Successfully capturing the spirit of a work is more vital than simply porting the text, and to that end, adaptations of manga properties don't always have to pull straight from the source to achieve it. Take, for instance, the Lupin the Third franchise which despite having six TV series, multiple films, and over a dozen TV specials ever since it hit Japanese airwaves in 1971, has never really had an anime that's directly lifted the combination of noir pulp and sexual exploitation present in the late Monkey Punch's original manga. The closest would be Sayo Yamamoto and Mari Okada's Lupin the 3rd: The Woman Called Fujiko Mine, but while it does lean heavily into the classic noir pulp present in the manga, it also critiques how the character of Fujiko is objectified as a femme fatale as often as it plays those tropes straight. Yet despite the lack of any direct adaptations, there has been a playbook for how Lupin and his compatriots operate as characters that has stayed more or less consistent across the decades (For instance, Lupin can play up being a gentleman thief, but should always be at least a little morally dubious, while Fujiko should always be looking to take advantage of Lupin's obsession with her so she can double cross him, etc.) and has allowed them to function in everything from wacky cartoon heists to political thrillers while remaining recognizable icons. That said, there have also been variations of Lupin that don't strictly follow these conventions, with the most famous example being Lupin the 3rd: The Castle of Cagliostro helmed by Hayao Miyazaki. Compared to nearly any other version of the character, Miyazaki's Lupin is unambiguously heroic, more of a thrill seeker than a thief. It is much more a Miyazaki film than it is a Lupin one. Even so, it is still an exceptionally well-made adventure film and one that's been held in high regard as much as the rest of Miyazaki's catalogue, so even if it's arguably not a great Lupin adaptation, that doesn't really take away from it being a solid movie entirely on its own merits.

Of course, while Lupin is one of the easier examples to point to for anime that have managed to work despite not directly adapting the manga they're attached to, it's far from the only one. One of the most successful examples of this is the 90's adaptation of Sailor Moon, which only very loosely followed the plot of Naoko Takeuchi's manga and was otherwise its own story with a much more episodic structure. While this episodic approach meant the story moved much more slowly, it also gave the anime more room to flesh out each Sailor Guardian individually, unlike the manga, which was much more focused on Usagi as the central protagonist. These changes largely worked to the anime's benefit, and Sailor Moon's massive success can be attributed as much to how well the anime staff transformed the Sailor Guardians into a cast of well-defined icons as to the strengths of Takeuchi's work on the manga. There's also the modern classic, DEVILMAN crybaby, which while being a more tonally faithful adaptation of Gō Nagai's Devilman manga than the 1972 TV anime (right down to including its grim ending), also takes a lot of creative liberties in the way it modernizes the setting and the ways it uses demons to explore repressed sexuality, while still managing to get across the manga's core anti-war message. To take this idea to its absolute extreme, you need look no further than the series Pluto by Naoki Urasawa. While its anime adaption is a pretty direct recreation of the manga, the manga itself is an adaptation of the story arc “The Greatest Robot on Earth” from Osamu Tezuka's Astro Boy, taking the original story's messages regarding the nature of prejudice and the futility of war that were originally aimed at children, and reframing them under a more adult lens. The end result is a story just as strong, if not better than the one that inspired it, and one that wouldn't exist if Astro Boy were never allowed to be adapted past its first anime in 1961.

That said, while creative liberties in anime adaptations can work better than they're generally given credit for, it's also important to acknowledge that attempts to deviate can just end up falling flat. One such instance is the 2008 anime adaptation of Rosario+Vampire, which, like many of Studio GONZO's manga adaptations from the early to mid 00's, only very loosely followed its source material and was otherwise its own show. In the case of this one, it took Akihisa Ikeda's monster high school series, which eventually transitioned from a standard harem manga into more of a harem-battle shonen hybrid, and gave us an adaptation that ended up removing nearly all of the battle shonen elements. This left it as just a regular harem anime, and a rather standard one at that.

There was also Tokyo Ghoul Root A, which promised to follow up on the first season's super condensed adaptation with an original storyline penned by the manga's author, Sui Ishida, but ended up deviating from those plans in favor of a season that loosely covered the remaining half of the first manga, but deviated just far enough to create some notable continuity errors with its sequel, Tokyo Ghoul:re. While Root A had its share of good individual scenes, and was somewhat held together by the strength of its director, Shuhei Morita, it was still a bit of a narrative mess, and this ended up harming the adaptation of Tokyo Ghoul:re, as even beyond its obvious pacing problems and change in directors, it was so divorced from the season that had come before it, that it was nearly indecipherable to anyone who wasn't already reading the manga.

If you're talking about adaptations reviled for making changes, it's hard to think of a more infamous modern example than the second season of The Promised Neverland. Like Root A, it only very loosely adapted the remaining parts of its original manga, but whereas Root A was still well directed despite its bad script, TPN's second season was a much bigger disaster. Not only did it attempt to convert 13 or so volumes worth of manga into a handful of episodes, but it covered all that in a way that showed an even worse understanding of source material than the first season by taking the final arc's extensive allegory for how those in power sow division among the different groups they've victimized to maintain their status, and simplifying it into a “both sides” argument regarding race relations. All of this resulted in a show that wasn't just weak by its own merits but one that has arguably hurt the manga's reputation by association, as the anime's failure has since cast a shadow over any other discussion of the series.

Strange as it might sound though, I'd actually argue that at least as far as Tokyo Ghoul Root A and The Promised Neverland season 2 are concerned, their biggest failings were less in being too different from their manga counterparts, and more that they weren't willing to be different enough in ways that could have helped these adaptations to have a stronger sense of identity, as their changes generally ranged from superficial, to ones that end up dumbing down the core messages of their source material instead of enhancing them. By going for halfhearted changes instead of fully committing to them, or simply opting for a more direct adaptation, we ended up with versions of these stories that failed to please anyone.

To come back to the subject of Fullmetal Alchemist, while the 2003 anime may not be a direct adaptation of the manga, that doesn't make it any less great. For one thing, its widely regarded status as an adaptation designed to be fairly 1:1 with the manga before veering off once it ran out of material is more than a little inaccurate. From the very beginning, it was intended to function as its own story, separate from the manga, since the manga was nowhere near completion, and rather than leaving audiences hanging, Arakawa encouraged the anime staff to create a self-contained story. With that framework in mind, its director, Seiji Mizushima, and writer Shō Aikawa took what was available of the manga and reworked its flashy action-fantasy elements into a narrative that feels a bit more subdued, one that takes its time exploring the themes of Arakawa's original work. In doing so, it arguably manages to grapple with the consequences of military fascism even more harshly than the manga by forcing the officers within the main cast to confront their past war crimes more directly, while using the conflict between people of Ishval and the Amestris military as commentary on the then ongoing invasion of Iraq by the US military. It also takes a pretty critical look at the concept of “Equivalent Exchange” presented in the story- the idea that gaining something requires an equal amount of effort or sacrifice to obtain it- and questions if such an ideal can really hold true in the reality of how inherently unfair the world actually is. Even though the 2003 anime looks at these themes through a more cynical lens than the manga or Brotherhood, it does still address them throughout its entire runtime, and in that respect makes for an excellent adaptation that shows a pretty high degree of respect for Arakawa's original work, even if it's not directly copying it beat for beat.

What makes a good anime adaptation can be trickier than it seems on the surface, and much like there's no one right way to create a story, there's no one right way to adapt one. Some anime adaptations shine best when they draw directly from their source material, while others use it as a launching point to stand on their own, and I think there's room for both. While direct adaptations will likely always remain the default, especially with manga more accessible than ever before, there's still value in ones that are allowed to run loose. Even if the results aren't always perfect, adaptations are as much a form of art as the stories they draw from, and, like any other piece of art, we tend to get the best ones when the people making them are allowed to express what they want.

discuss this in the forum (2 posts) |